|

This was going to be the first in a series of posts where I asked for help in identifying the map in the film, but then as I was putting up the image I realised that the map behind these dinner guests is of South East England, so there is no mystery to solve. Tomorrow's map will be more mysterious.

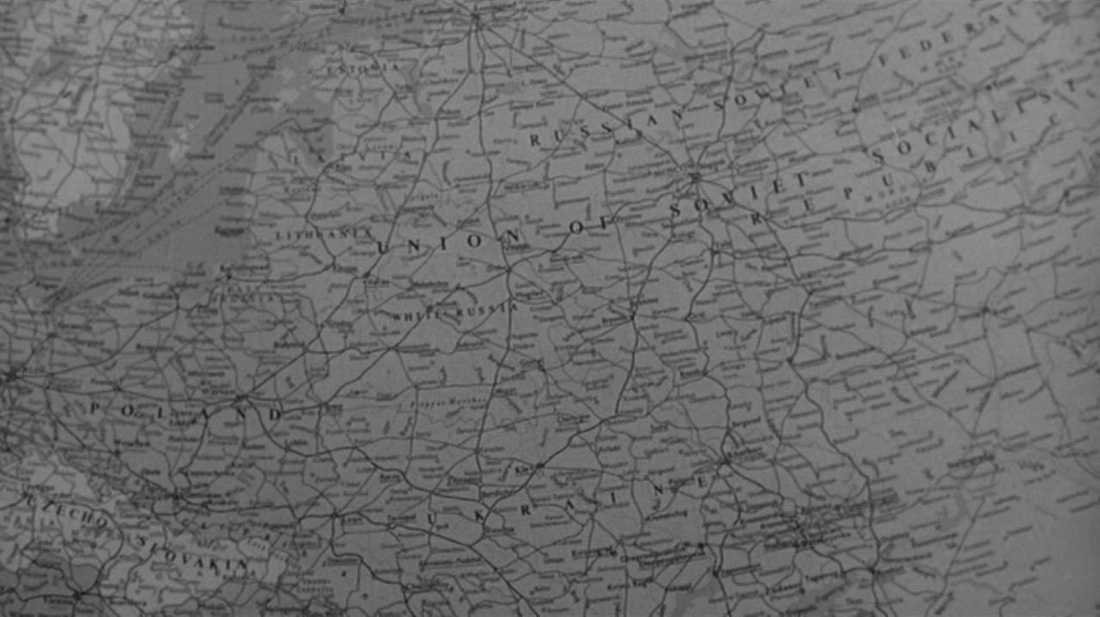

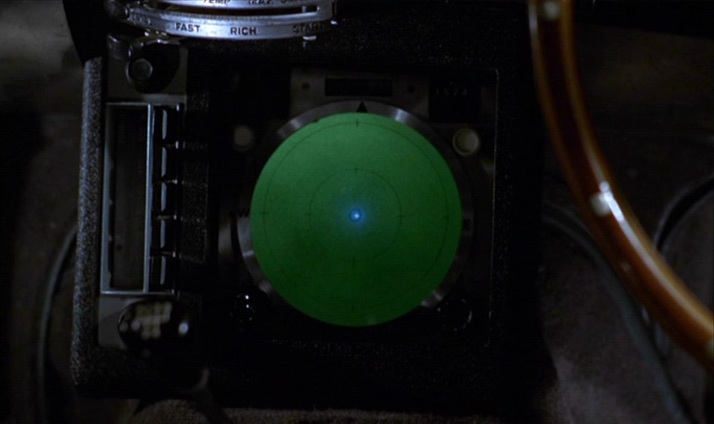

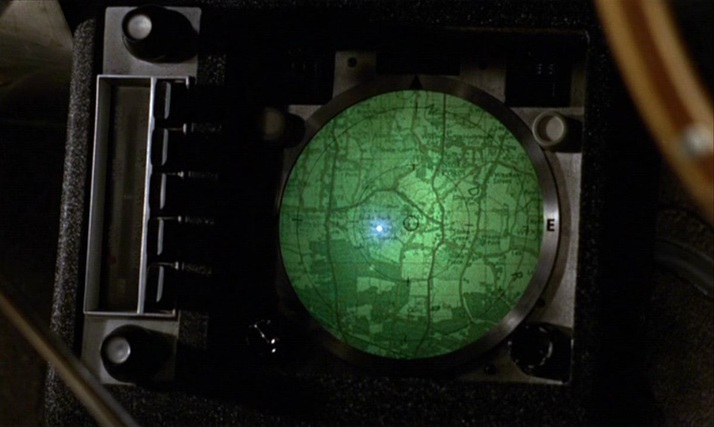

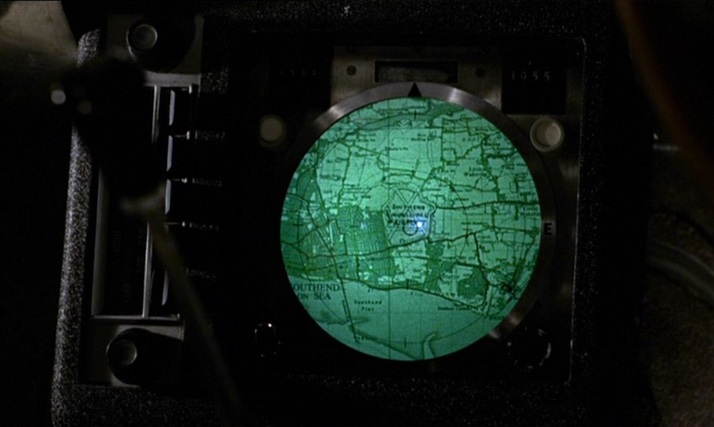

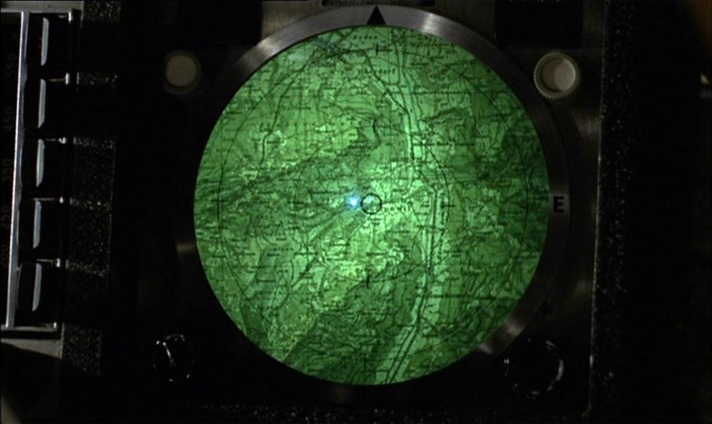

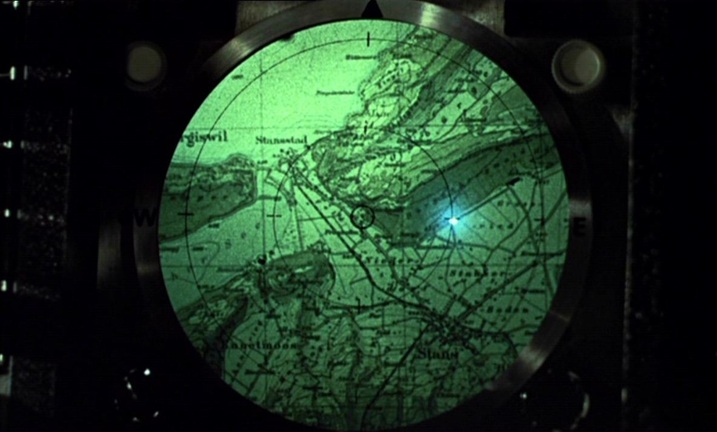

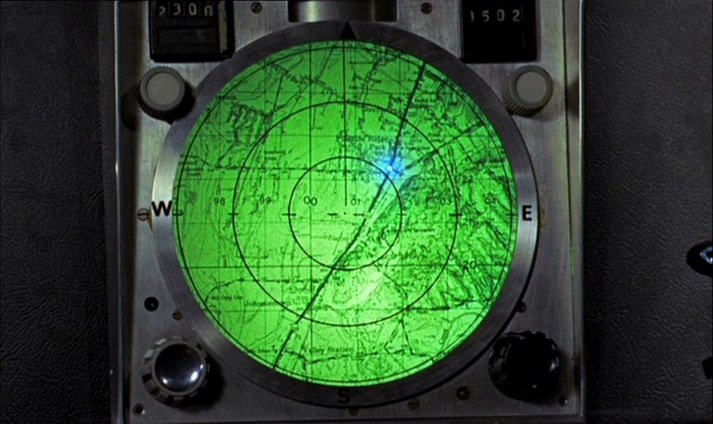

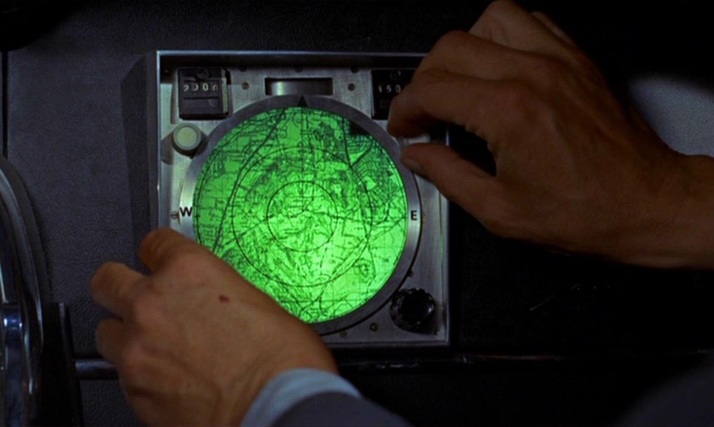

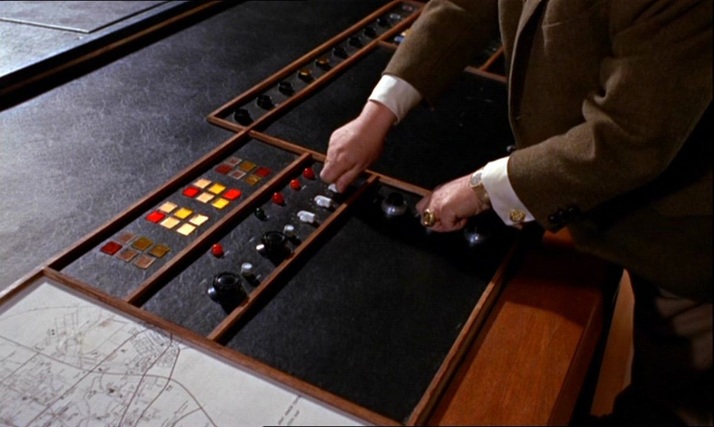

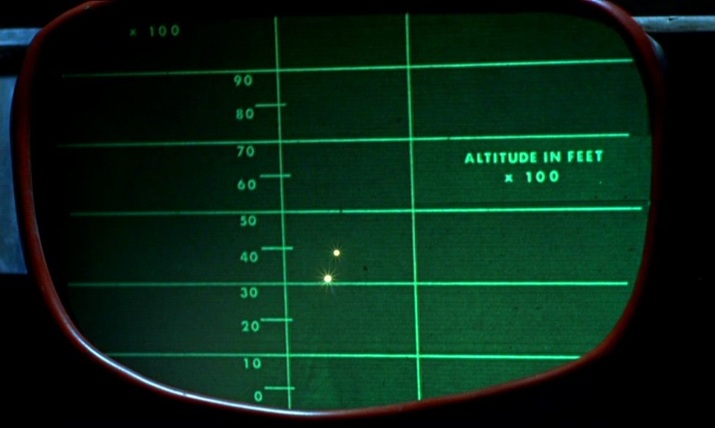

M’s outer office has the familiar wall maps that establish the global scale of MI6’s operations (see here for the first instance of this in the Bond canon): Bond’s in-car tracking device takes us from Stoke Park in Buckinghamshire to Southend Airport in Essex, then to Geneva. From there we go north (I can’t quite make out where), then on to Goldfinger’s factory between Stans and Stansstad, just south of Lucerne: When the film cuts from the device to the terrain it represents, an irony is apparent in the contrast of horizontal (the map) and vertical (the mountains). Plotted against each other, you get the diagonal lines of one of cinema’s more famous mountain sequences: A similar tracking device later shows us the vicinity of Goldfinger’s lair near Fort Knox (Kentucky), but the efforts of the US agents to follow the plot on it are thwarted by Oddjob, and the device breaks down when the car it is tracking is crushed. Unlike the lairs of so many other such villains, Goldfinger’s does not have large wall maps as décor. He has two smaller, horizontally placed maps at his desk but, as expressions of his power over the world through representation, his preferred alternatives to mapping are the aerial photograph and the scale model: (Goldfinger is at one here with the film’s liking for aerial views.) The film’s cartographic configurations conclude with the tracing of a vertical trajectory, as Bond and Pussy Galore parachute from a plane: For further comment on the spatial machinery of this film, see: (e)space & fiction

‘Britannia Hospital’ is Friern Hospital, formerly the Colney Hatch Asylum. Leonard Rossiter is standing in front of maps of the asylum, and in a key scene the itinerary of a planned royal visit to the hospital is traced on a blackboard. Most of the maps in Britannia Hospital are of the hospital, limit cases of the local and particular, but given that the hospital is a synechdoche of Britain, these maps are also, necessarily, national. In this film’s predecessor, O Lucky Man!, the map was the territory, an index of the protagonist’s itinerary around Britain, before arriving in New Southgate.

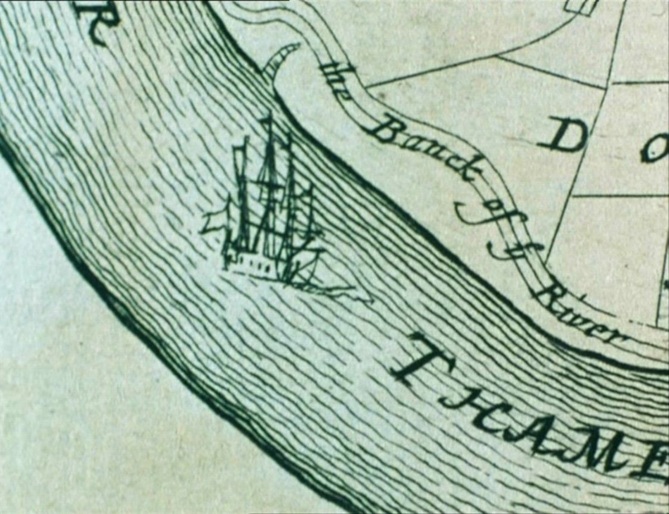

‘His research into the historical and economic development of the river led him to the conclusion that his film needed to capture the “interpenetration of the natural and the fabricated”. This led to an obsessive fascination with maps and charts of the Thames. “I realize that this is because the topography of subject is most crucial. The river is the penetration of one element by another. They are equally interdependent upon each other for the river's existence”. A study of the conditions and topography of a river is actually a study of time and change, for any river has its own pace in nature. “I want to make a film that is an observation of the River Thames. It will be a landscape film, a documentary film and a film about a journey…”.’

Jane Chapman, ‘William Raban: Thames Film’, in Documentary in Practice: Filmmakers and Production Choices (Malden MA: Polity Press, 2007), p.59. 'In the film The Good Companions, Saville establishes the narrator-narratee correlation immediately in the prologue, which Henry Ainley (1879-1945) narrates in a voiceover, in conjunction with a still shot of a map of the counties of origin of the three main characters and a fourth county, to be their place of meeting, blackened in:

"This is a story of the roads and the wandering players of modern England, the story of how Jess Oakroyd left his home in Bruddersford and took to the road, and how Inigo Jollifant marched out of his school at Washbury Manor, and how Elizabeth, daughter of old Colonel Trant, suddenly went off into the blue and how chance brought these three to one small town in the Midlands, together with a broken-down troupe of entertainers, the Dinky-Doos. At Bruddersford there was working a carpenter, Mr. Oakroyd." Here cinematographer Bernard Knowles (1900-1975) uses a cross dissolve to move from a close-up of Mr. Oakroyd's county on the map to a close-up of the back of Mr. Oakroyd's head.' Paul Matthew St Pierre, Music Hall Mimesis in British Film, 1895-1960: On the Halls on the Screen (Cranbury NJ: Rosemont, 2009) p.139. |

|