Time, place and cars in Week End (Godard 1967)

This post is a close examination of Week End's famously long tracking shot alongside a traffic jam, with some further comments on time and place in the film. At the end of the post I count and (thanks to the IMCDB) identify the vehicles involved in the traffic jam.

Time (1)

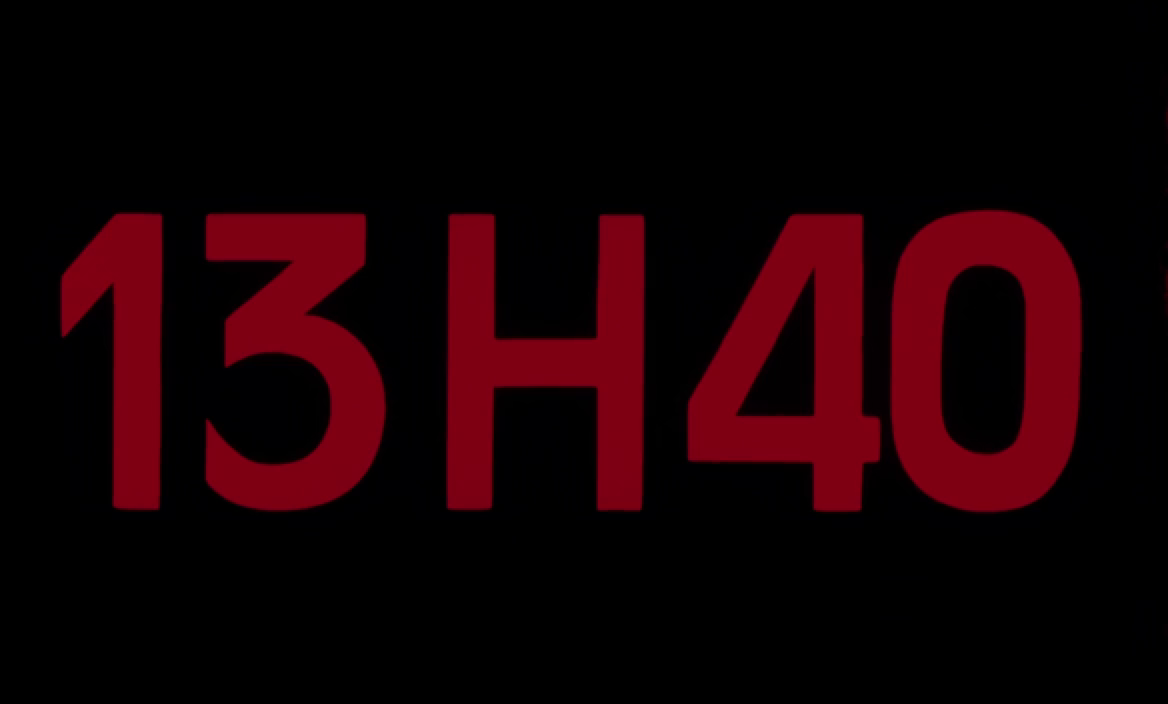

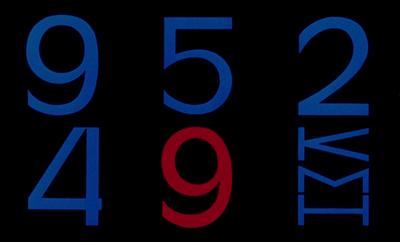

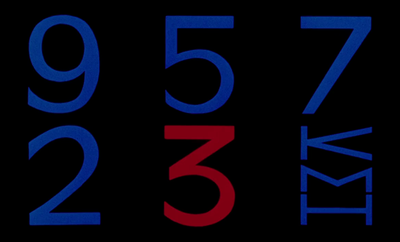

In the version of Week End that I am watching, the traffic-jam sequence begins at 16.14 and ends at 24,04, so lasts in total seven minutes and fifty seconds. At 18.48 the shot is interrupted by a title that reads '13H40', then at 18.51 by a title that reads 'WEEKEND' and at 18.54 by a title that reads '14H10'; each of these titles is on screen for less that a second:

In the version of Week End that I am watching, the traffic-jam sequence begins at 16.14 and ends at 24,04, so lasts in total seven minutes and fifty seconds. At 18.48 the shot is interrupted by a title that reads '13H40', then at 18.51 by a title that reads 'WEEKEND' and at 18.54 by a title that reads '14H10'; each of these titles is on screen for less that a second:

There are two conflicting temporalities on display here: in the space of six seconds, thirty minutes have passed, according to the titles. It is common for a cut to effect ellipsis, but here our strong sense of the continuity of pro-filmic action and of camera movement makes that ellipsis seem unfeasible. We are more likely to believe in the six seconds of pro-filmic or story time, rather than the thirty minutes of typographic or discourse time.

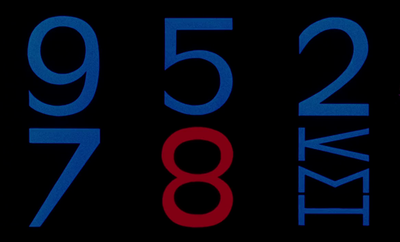

A further complication, however, suggests we would be wrong to do so. Between the end of the shot that precedes the title '13H40' and the beginning of the shot that follows it the shot has changed slightly, and not only as much as would be allowed by the second or so the camera would have continued tracking as we read the inserted title:

A further complication, however, suggests we would be wrong to do so. Between the end of the shot that precedes the title '13H40' and the beginning of the shot that follows it the shot has changed slightly, and not only as much as would be allowed by the second or so the camera would have continued tracking as we read the inserted title:

It looks like the camera is now further from the coach. This may be an effect of the camera panning to the left as it tracks and so changing the angle, but I suspect that even so simple an adjustment would take longer than the second of screen-time accorded the title, hence I suspect that the title covers an ellipsis. (I'll confess that I'm not absolutely sure of this.)

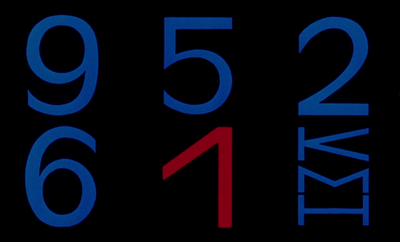

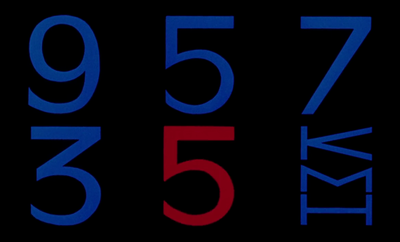

By contrast, between the end of the shot preceding the title 'WEEKEND' and the beginning of the shot that follows it, there is an almost perfect match:

By contrast, between the end of the shot preceding the title 'WEEKEND' and the beginning of the shot that follows it, there is an almost perfect match:

The title's second of screen-time is just what it would take for the camera to reveal the 'O' and the 'C' of 'AUTOCAR' written on the side of the coach. What this means is that the title has not interrupted the real time of this sequence-shot. In the editing, the title has replaced some frames of the shot. (I think it is reasonable to continue calling this a sequence-shot ('plan-séquence'), even if, effectively, I am treating the segments separated by titles as separate shots.)

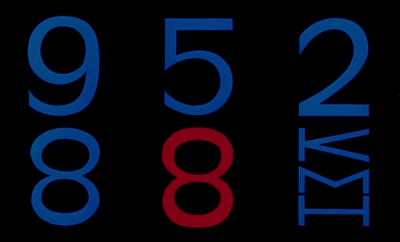

Things become more complicated when we compare the end of the shot that precedes the title '14H10' and the beginning of the shot that follows it:

The beginning of the succeeding shot is blurred because the camera is panning quickly to the right, catching up with the protagonists' car that has passed the coach on the other side. The speed of the pan could account for the ground covered in the title's second of screen-time, but there are changes in the staging that the camera's rapid movement cannot explain. The woman in the reddish coat in the second shot above is the same woman who is speaking to a man in the first shot. In one second she has broken off her conversation and rushed to the front of the coach, though in the second shot she is only walking. I don't think that could have happened in one second. I am certain, moreover, that the woman knitting in the first shot could not have in one second stopped knitting and rushed forward to join those haranguing the protagonists in the continuation of the second shot. That is she, below, third from the left:

The '14H10' title covers in one second an ellipsis of five to ten seconds. Whether it replaces frames removed from one continuous shot or disguises a transition to a new shot doesn't really matter. Either way, this sequence is broken by that title into two shots, the first lasting two minutes and forty seconds, the second lasting five minutes and ten seconds. If, as I suspect, there is also an ellipsis covered by the '13H40' title, then the sequence comprises three shots, with a five-second shot between the two longer ones.

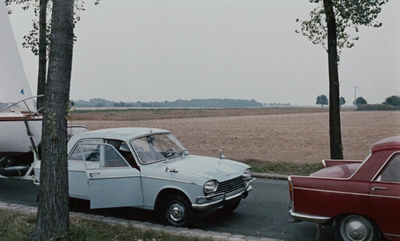

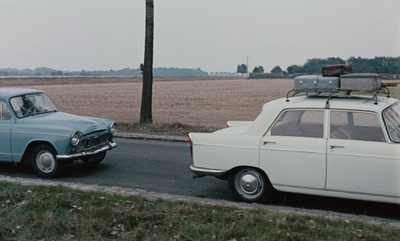

There were certainly alternative takes of the shot, since the French trailer for the film uses two segments that do not correspond to what we see in the film. The first two images below are from the trailer, the second two from the film. The red Mini is positioned in the same place but the movement of cars around it is different. The light blue Neckar Jagst is filmed from a quite different angle:

Place

The couple set out to reach Oinville, though they never specify which of four possible places called Oinville they are heading for: Oinville-sur-Montcient (78), Oinville-Saint-Liphard (28), Oinville-sous-Anneau (28) or just plain Oinville (28), near Mainvilliers. Baecque (Godard p.387) decides that it must be the first of these, and furthermore affirms that Godard shot 'the longest tracking shot in the history of cinema … on the D913, leading from Meulan to Vétheuil, and more exactly near Oinville-sur-Montcient, the sign for which we see in the film'.

However, - as you can see above - the sign we see only reads 'Oinville'. We can also see, I think, that this is not an authentic sign - the name Oinville has been stuck onto a sign at the entrance of some other village.

However, - as you can see above - the sign we see only reads 'Oinville'. We can also see, I think, that this is not an authentic sign - the name Oinville has been stuck onto a sign at the entrance of some other village.

I don't know what name was originally on that signpost, but I do know it wasn't a place anywhere near Oinville-sur-Montcient, since the film never went anywhere near there. Hence, of course, the famous long tracking shot of a traffic jam was not filmed, as Baecque claims, on the D913. The tree-lined stretch of road we see in Week End is the D91 leading from Guyancourt to Fourcherolles, more exactly near the junction with the D195:

I don't know on what basis Baecque came up with this precise but completely different location for where the sequence was filmed: 'along the tree-lined departmental route D913 leading from Meulan to Véthueil, and more exactly near Oinville-sur-Montcient'. It is understandable that he not know something, but incomprehensible that he would then invent information to cover his ignorance (though I have found him making up false quotes before - see at the end of the post here - so perhaps I shouldn't be surprised).

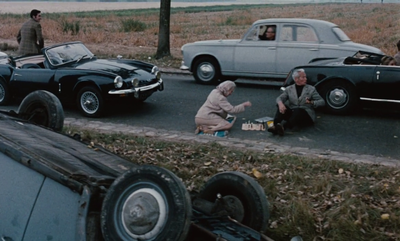

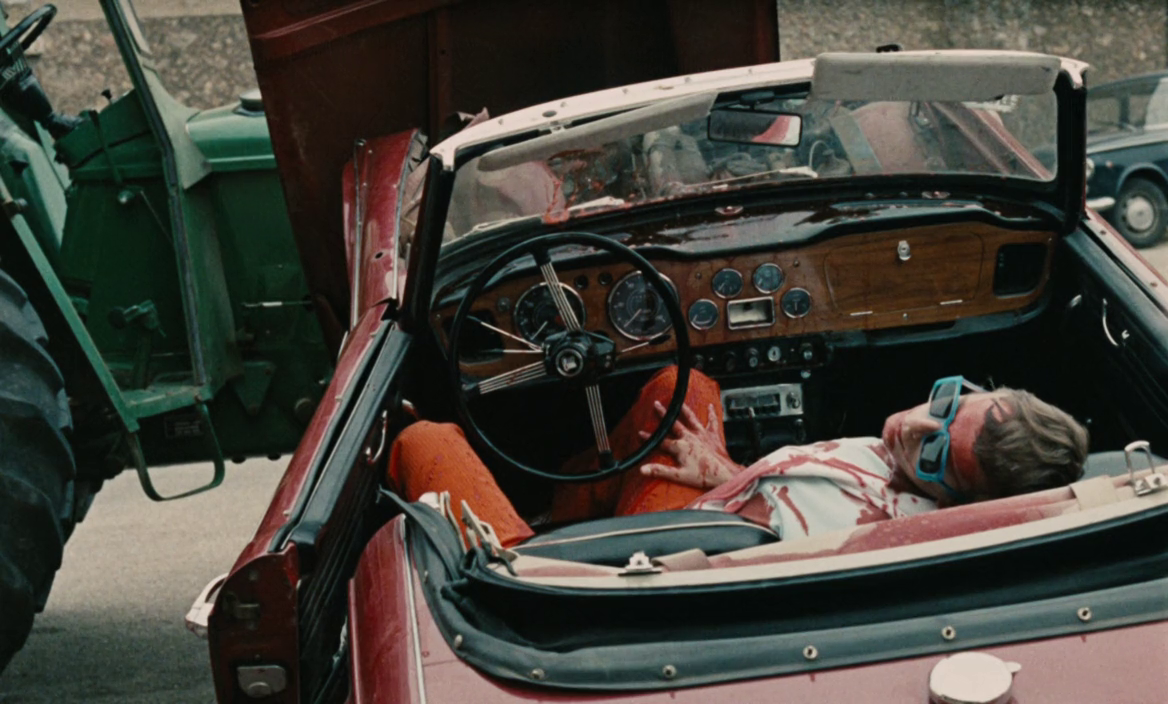

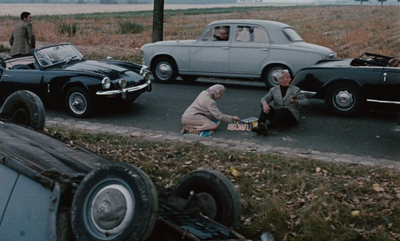

Baecque's description of the sequence is lengthy but wrong: he concludes it by saying that the traffic jam is caused by an accident where we see a man dead in an open-top sports car and a young woman accusing a farmer and his tractor of causing the accident:

Baecque's description of the sequence is lengthy but wrong: he concludes it by saying that the traffic jam is caused by an accident where we see a man dead in an open-top sports car and a young woman accusing a farmer and his tractor of causing the accident:

This is an accident from the following sequence, which has nothing to do with the traffic jam and the roadside tracking shot. As I constantly have to say to my students: every piece of information in books by Baecque needs to be checked. He is a consistently unreliable and lazy writer, and a poor scholar.

I still have some work to do on the places of Week End, but I can say already the protagonists' trek across France doesn't actually take them very far. The traffic jam was on a road leading from Guyancourt, a town just south of Versailles. When they are taken prisoner by Joseph Balsamo, they drive back down the same stretch of road on which was filmed the traffic jam.

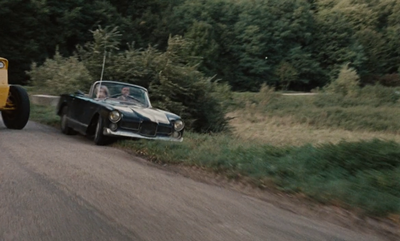

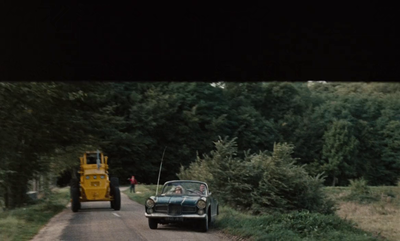

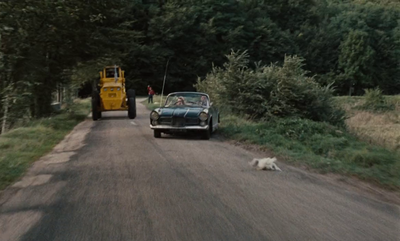

The accident with the sports car and tractor (a 1965 Triumph TR4A and a 1962 Deutz D50.1 S - see the Internet Movie Cars Database) happens in Guyancourt, and when they finally are in 'Oinville', that too is Guyancourt:

The accident with the sports car and tractor (a 1965 Triumph TR4A and a 1962 Deutz D50.1 S - see the Internet Movie Cars Database) happens in Guyancourt, and when they finally are in 'Oinville', that too is Guyancourt:

The farmyard where Paul Gégauff plays Mozart on the piano is the ferme de Villeroy in Guyancourt:

I haven't yet found the apartment building from where they set out. It is supposed to be in Paris, but it wouldn't surprise me to learn that it too was in Guyancourt:

My guess is that all of the unidentified places in the film - roads, houses, forests, lakes, fields - are somewhere near Guyancourt, which seems to have served as a hub for the film's location hunter, Claude Miller. Miller is a link with Guyancourt's other claim to a place in cinema history, as a location for Robert Bresson's 1966 film Au hasard Balthazar, on which Miller was an assistant. Guyancourt is where Godard first met Anne Wiazemsky, on the set of Bresson's film. I haven't matched any locations from the two films, but there are two or three details in Week End that look like they might be echoes of Au hasard Balthazar. The car accident provoked by local hooligans is, in Bresson's film, a low-key anticipation of Godard's multiple crashes; the zoo animals on trucks in Godard's traffic jam echo the zoo scene in Au hasard Balthazar; and the tramp who rapes Corinne in a ditch is played by an actor from Bresson's film, Jean-Claude Guilbert.

Time (2)

I introduced a screening of Week End on March 1st 2017, as part of the Kino Klassika Foundation's season 'A World to Win: A Century of Revolution on Screen'. In my introduction I focused on various versions of time in the film. Below is a transcript, tidied up slightly and corrected in one place; you can see the raw thing here. (The introduction was improvised so please forgive a certain roughness of expression.)

Week End is a film I like particularly because it relates to two of my chief research preoccupations: 1/ intertextual reference in film – there are many texts cited in Week End, an edition with footnotes would be a very useful thing; 2/ place in film – Week End is very much a film about France, and about particular areas of France.

This introduction focusses on a third area: how Week End engages with time. It has a peculiar, a very specific, perhaps a unique way of engaging with time in relation to film. A keyword for Week End is speed.

After a preamble, lots of conversation, lots of quotations from Georges Bataille, the principal characters set out on their journey, manifesting speed, you’d expect – they need to get somewhere quite urgently. And the first thing you they encounter is a traffic jam, shown in what has been commonly called the longest take in cinema history. At seven minutes and fifty seconds, it may well have been that at the time. It’s a very long tracking shot along a stretch of road in the countryside. It’s very famous, the thing that people refer to most often in relation to Week End.

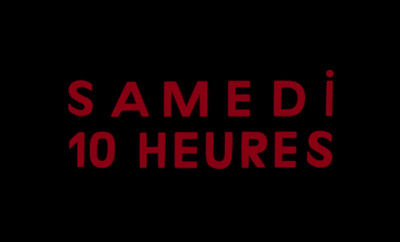

Speed is the essence, and that encumbrance to speed which is a traffic jam is right there at the beginning. Once the protagonists get beyond the traffic jam, which they do quite quickly, they set off and move quite fast. The wife complains to the husband that he’s not driving fast enough, he doesn’t know how to use the right gears, but they are heading quite quickly towards their destination. The way in which this is presented to us, which is one of the ways in which the film intervenes in relation to time, is with inserted titles. The film has graphically striking inserted titles, and they give us a sense of where we are exactly in time: Saturday 10.00, Saturday 11.00, and then 13.40, 14.10, Saturday 15.00, 16.00, 17.00. Our progress through the day is being marked quite clearly.

There is a problem here in relation to that long moment of real time, the seven-minute-fifty-second tracking shot, which fits a certain kind of theoretical concern about how cinema should just show the world in front of you, and if you don’t cut, if you don’t use montage, then you can just put the camera in front of the object and film it for as long as the object takes to be filmed, and there you have the world represented by cinema. That’s what that shot offers, except that there are those two titles that interrupt, one saying that the time is 13.40, the next saying that the time is 14.10. As you watch the sequence, that time does not pass, there’s no suggestion that in the seven minutes and fifty seconds it takes for that shot to play out that we have somehow had the ellipsis that would allow for half an hour to have passed.

There is a conflict and a contradiction between what the titles are doing in relation to time and what cinema is doing with its camera. That accentuates itself as we progress through the film. For the first day of their weekend, Saturday, we have the markers of hours and minutes. We also have, in relation to the theme of speed, a title that shows numbers progressing very quickly. This looks like a speedometer or a kilometre reader – I can’t quite work out exactly what it’s doing, you might know better:

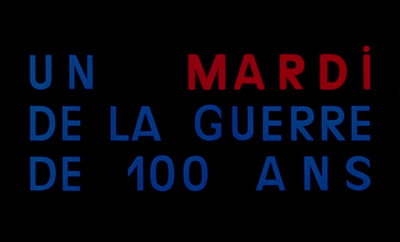

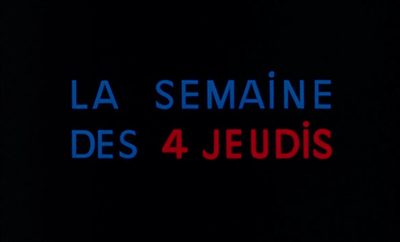

But then, as the titles progress, they don’t tell you the time of day, they tell you what day it is. We go to a title that elliptically refers to Sunday, another refers to Monday by reference to the title of a literary text, then there’s 'a Tuesday in the 100 Years War'. For some reason I haven’t worked out, Wednesday isn’t there; then you get 'the week of four Thursdays' and 'a Friday far from Robinson and Mantes-la-Jolie', referencing Robinson Crusoe but also a town south of Paris called Robinson. We are still following the principal characters through their journey, and it’s taking a very long time, much longer than they thought: it should have taken the weekend, they needed to get where they were going by Monday.

After the days are marked with titles, we then get months. Through an elliptic literary reference, the first month mentioned is in the title of William Faulkner’s novel Light in August. And then we have a reference to the massacres of September, an event in the French Revolution, followed by a title that says ‘Language of October’, clearly pointing to the Russian Revolution:

It’s slowing down. It’s now taking them months to get to their destination, not days. And then something very strange happens. Instead of the names of the months that we are familiar with, in the the course of the last half hour of the film, we get titles that point to the names given in the French Revolution to an entirely new set of months. In the French Revolution they restarted the calendar from year zero, they gave new names to months and new names to days. Here we have Thermidor, the name for a month in a season of extreme heat July-August, then Pluviôse, a name for a month in a season of rain, January-February, and then Vendémiaire, a name for a month in the season of harvests, September-October:

That seems to replicate the expression of the succession of time by months, except that at this point it’s going backwards. We go from July back to February then back to September. So time, in the way it’s marked by these titles, comes to a halt and then starts moving backwards. And what it’s moving back towards is the thing that those Republican names of months refer to, the French Revolution. There are other mentions in the film of the French Revolution, which are the counterpart to the film's reference to current time, a real time of potential revolution in Africa, of potential revolution in the United States. Reference to the French Revolution takes us back to 1791-92, the moment where contemporary history might be said to begin, the Age of Revolutions. Time seems to stop there, but actually by the end of the film we are in a different time entirely. A time of a certain kind of revolution, an unreal and derisory revolution, that looks like we’ve gone back to pre-history, to something like the reverse of the Golden Age, a time when cannibalism was the norm, and where mutual violence would be what you might expect between competing societies. That’s the point at which the film ends, and it ends by making a connection between ‘bourgeois horror’, to quote Mao, who is quoted in the film, and a time of pre-historical horror.

I don’t think this film, or indeed any other film by Godard in 1967, or any other film in 1967, is thinking about May ’68. Films can’t think in advance. Week End is not premonitory of the kinds of social change and social unrest that will happen in May ’68, it doesn’t figure that kind of unrest. It talks about a complete different, dystopian moment of the breakdown of society.

On that note, with the possibility of the breakdown of society, I remember there is one thing I wanted to mention in relation to time in Week End. There is a moment where film-time threatens to come to an absolute halt, when we seem to be seeing the film jam in the projector. It looks like the film will stop as the journey stops, with the destruction of the car:

On that note, with the possibility of the breakdown of society, I remember there is one thing I wanted to mention in relation to time in Week End. There is a moment where film-time threatens to come to an absolute halt, when we seem to be seeing the film jam in the projector. It looks like the film will stop as the journey stops, with the destruction of the car:

This disruption of the image is a formalised representation of the medium's breakdown, during which the medium continues to play with time, as the disrupted images are shown out of sequence: shots of the car burning are followed by shots of the car still on the road. It is difficult to fix exactly what this sequence is doing, and for some exhibitors the difficulty was too much - in some prints this passage was removed, as if it were a mistake needing correction.

(The print we showed at the Regent Street Theatre appeared to be intact.)

(The print we showed at the Regent Street Theatre appeared to be intact.)

Cars

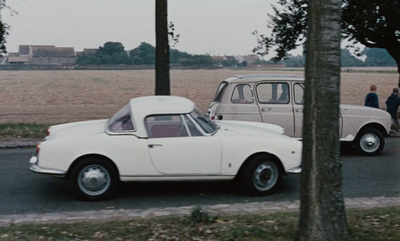

The car the protagonists set out in is a 1960 Facel Véga Facellia Cabriolet - my thanks to the IMCDB. The Internet Movie Cars DataBase has identified many but not all of the vehicles in Week End.

|

In the traffic jam there are forty-two vehicles, including the horse-drawn cart and the car-drawn yacht. Three vehicles are approaching at the beginning of the shot (right), five pass down the route in the opposite direction, and there are two in the distance at the end of the shot. Adding to these the five wrecked cars by the roadside, the two recovery vehicles and the police motorcycle, and the Facel Véga, there are in total sixty-one vehicles in this sequence.

|

|

1/ Renault Ondine? (not identified by the IMCDB)

|

2/ Simca 1000-950, 1962

|

|

9/ Citroën 2CV (not identified by the IMCDB)

|

|

11/ another Renault Goélette Plateau? (not identified by the IMCDB)

|

|

13/ Mini (not identified by the IMCDB)

|

|

17/ a horse and cart (not identified by the IMCDB)

|

|

20/ Simca 1000? (not identified by the IMCDB)

|

|

22/ Simca 1000? (not identified by the IMCDB)

|

|

27/ Renault 4CV? (not identified by the IMCDB)

|

|

34/ a boat (not identified by the IMCDB)

|

|

37/ Renault Ondine? (not identified by the IMCDB)

|

|

39/ Peugeot 404? (not identified by the IMCDB)

|

There are four wrecked cars by the roadside:

And at the end a further three that were involved in the fatal accident that created the traffic jam. There are two recovery vehicles here and a police motorcycle:

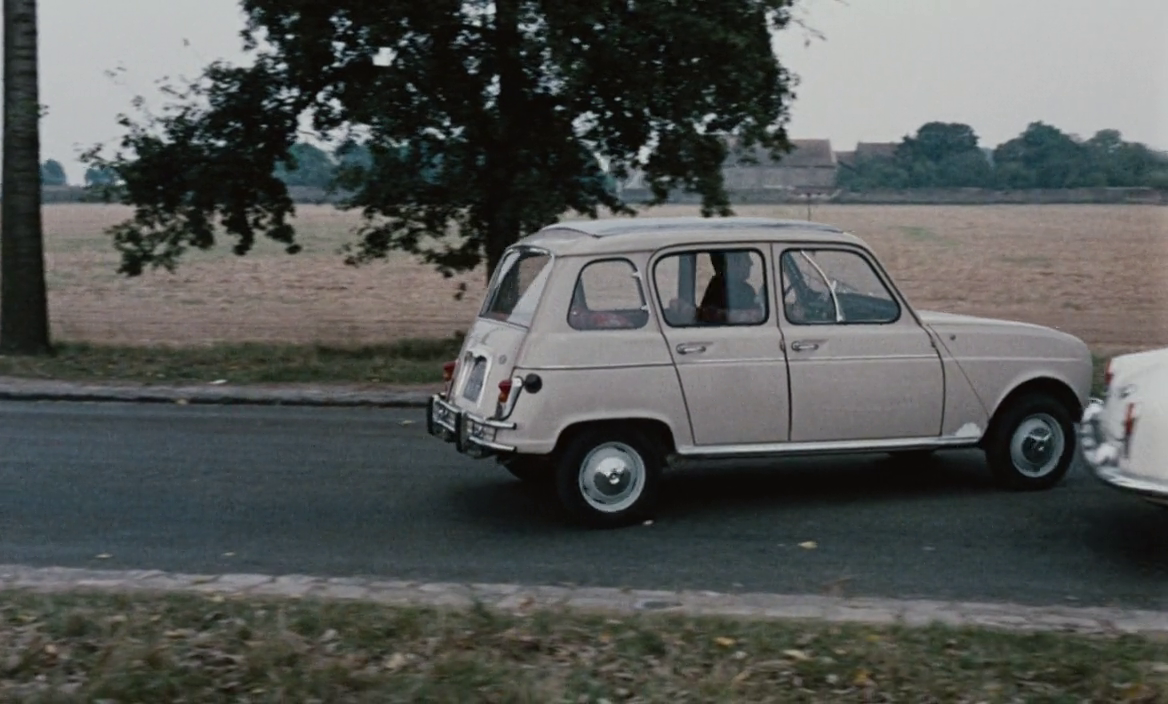

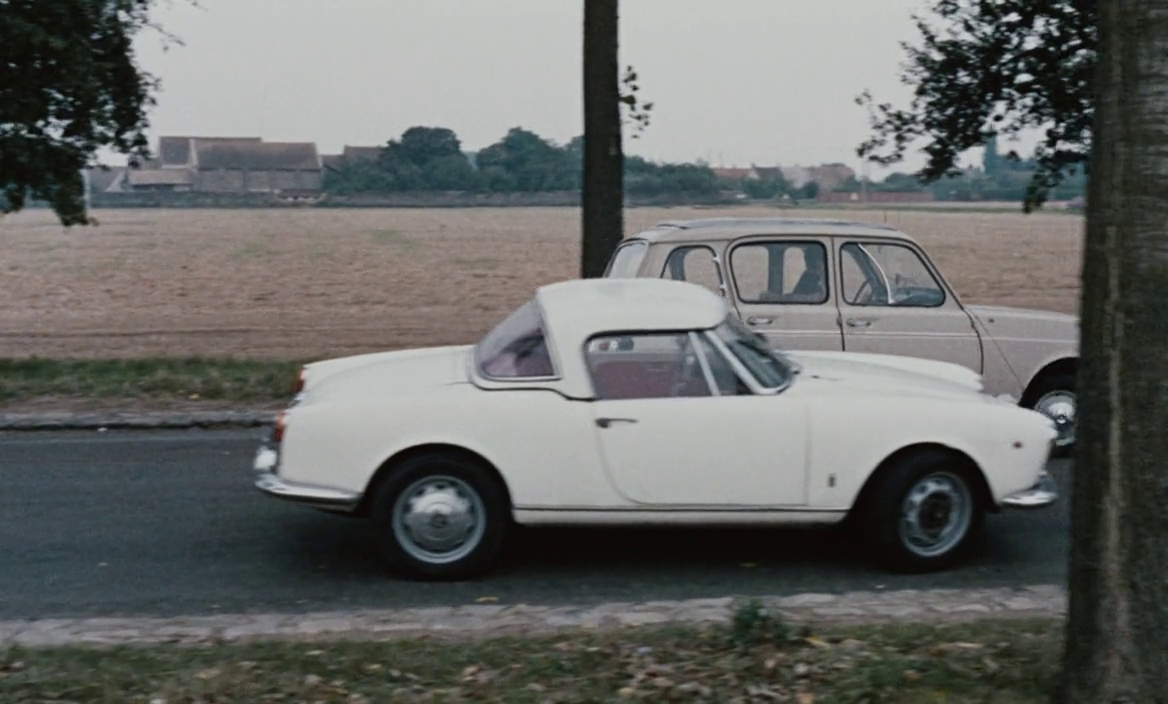

Five vehicles pass in the opposite direction, including a Citroën 2CV, a Renault 4 and a Citroën DS:

As the sequence closes can be seen two cars parked in the distance, one waiting to come in the direction of the traffic jam, another parked on the turning taken by the protagonists' Facel Véga: