|

(This is a version, with added images, of the introduction I gave at the NFT on September 12 2018 to Jean Renoir's 1955 film French Cancan. The viewers also had as Programme Notes David Thompson's excellent 2011 piece on the film (here), so all I did was make a few comments about the reference to painting in the film and about its chronology.) |

In his own introduction to French Cancan, Jean Renoir played down the importance of the subject, saying that the important thing for him was ‘the cinematograph’, that is the inscription of movement. The movements he was keen to register were simple ones, like a woman’s gesture as she arranges her hair, or her breathing as she sleeps.

|

He then makes a comparison with Impressionism, of which his father was of course a leading exemplar. Impressionism, he says, succeeded in making the subject of a painting a secondary concern, and he tells of his father’s anger when a dealer wanted to call a painting of a young woman with her head slightly lowered, La Pensée, ‘Thought’. ‘In my paintings there’s no thinking’ he said - 'Dans mes tableaux on ne pense pas.' Jean Renoir is more or less saying that his film French Cancan is about nothing, which is a claim with great pedigree. Flaubert had said the same of Madame Bovary. But there are still some things that I'd like to say the film is about. |

French Cancan and painting

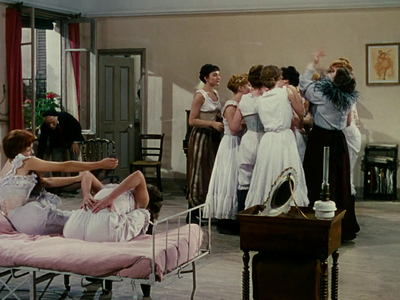

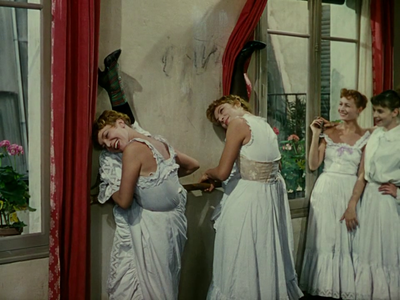

Raymond Durgnat succinctly summarises the film's relation to painting:

A scene cut from French Cancan showed Degas, Pissarro and Van Gogh drinking at a café terrace. Here they are in a production still:

Here, drinking at a café terrace, are Toulouse-Lautrec, Seurat and Anquetin, from John Huston's Moulin Rouge (1952):

And here, from Lust For Life (1955), are Van Gogh and Gauguin at a café terrace:

In Huston's Moulin Rouge the relation between things filmed and things drawn or painted was, somewhat crudely, presented. Minnelli did something similar in the ballet sequence of An American in Paris in 1951, and would do so again in Lust For Life.

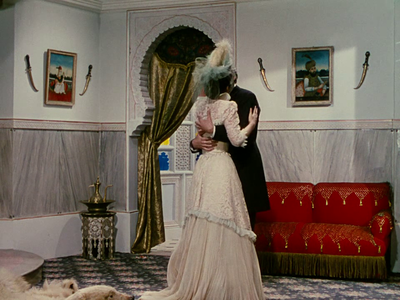

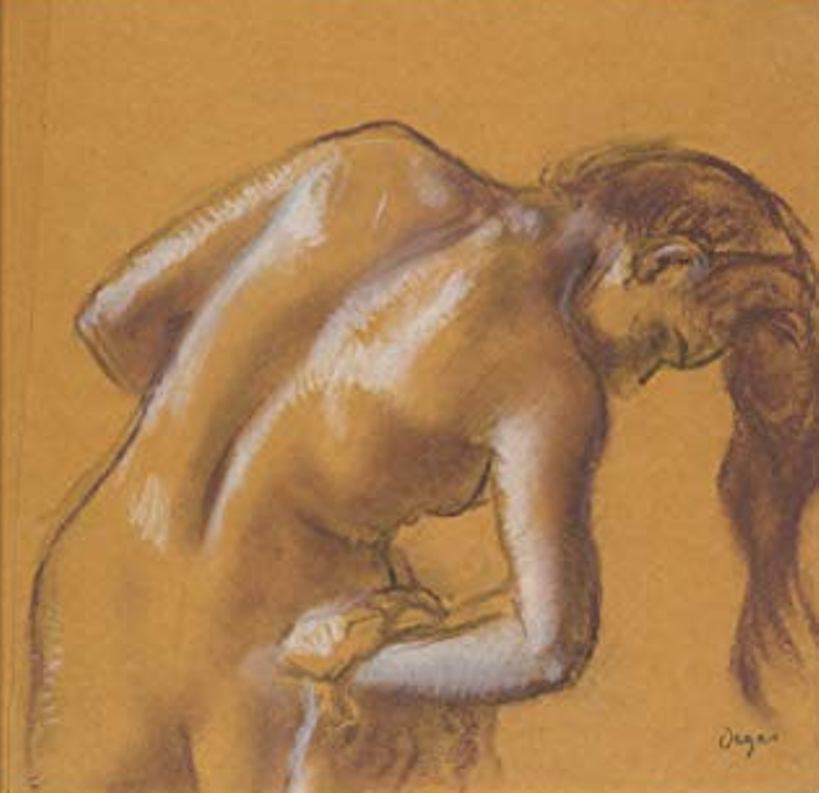

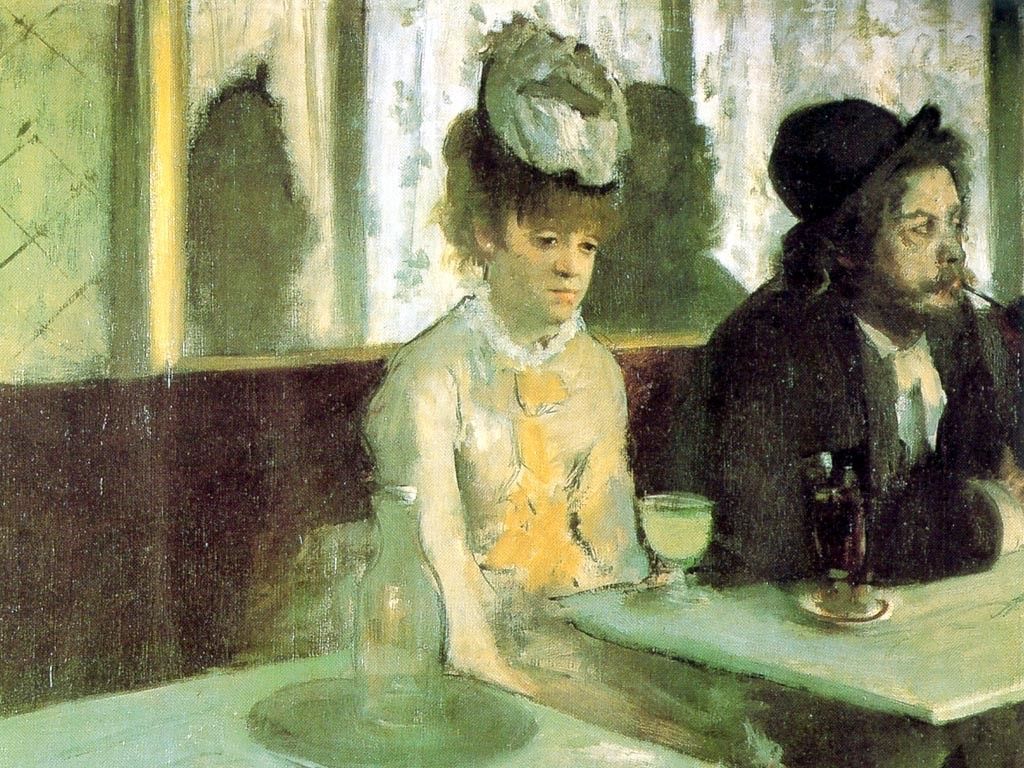

Renoir’s film avoids that kind of crude mimicry - it doesn’t, as far as I can tell, recreate any specific Impressionist paintings. At most, we can see here and there a coincidence of subject matter, especially if we think of Degas’s dancers. A woman washing may make us think of Degas, and there is a woman drinking alone, momentarily, who may evoke a famous painting by Degas, but the differences are as strong as the similarities.

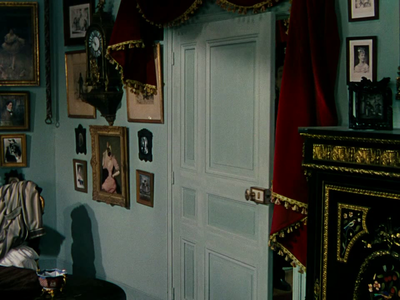

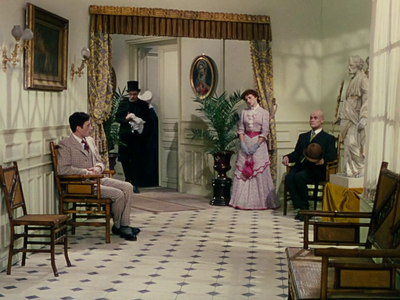

Though there are several paintings on display on the walls of French Cancan, of differing styles, none is I think an Impressionist painting:

It might be interesting to identify some of the art used as décor in the film:

All suggestions welcome (email here, please).

We might imagine that the pleinairiste painter shown at work on the Butte is an Impressionist, but we can't be sure since we don't see his work:

Here, by contrast, are Gauguin and Van Gogh at work, from Minnelli's Lust For Life:

There is irony in Renoir's depiction of a painter, since the open air in which he is painting is, like all of the exteriors in French Cancan, a space created in the studio:

It is a commonplace to describe the studied combinations of colour in French Cancan as painterly, but the film's painterliness is only superficially, if at all, Impressionist. Renoir's properly Impressionist film is Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe (1959):

It is reasonable to think of the carefully controlled colour palette of French Cancan as painterly, but analogies between film and painting are revealing only through differences. The composition of the film cannot be the equivalent of what an Impressionist painter would do. The combinations of colour are the result of collaboration - between the production designer (Max Douy), the costume designer (Rosine Delamare), the cinematographer (Michel Kelber), the accessoiristes, and others. All of these are organised and orchestrated by Renoir, but not in a way that allows us to compare him with a painter, with his father, for example.

The pertinent comparison is with film’s central character, Danglard, who organises the creation of the Moulin Rouge and the revival of the Cancan. When he says that the only thing that counts is what he creates he becomes a figure for Renoir as the creator of French Cancan. Such figures can of course be antithetical.

The pertinent comparison is with film’s central character, Danglard, who organises the creation of the Moulin Rouge and the revival of the Cancan. When he says that the only thing that counts is what he creates he becomes a figure for Renoir as the creator of French Cancan. Such figures can of course be antithetical.

French Cancan and chronology

French Cancan is about the creation of the Moulin Rouge, a historical event, dated October 6th 1889. But in the same way that French Cancan doesn’t use the real names of the people involved in that event - Charles Zidler becomes Henri Danglard (though 'Zidler' is there in 'Zizi', La Belle Abbesse's pet name for Danglard) – so it doesn’t use the specific dates associated with it. Instead, the film brings together markers of time from a period of about five years.

|

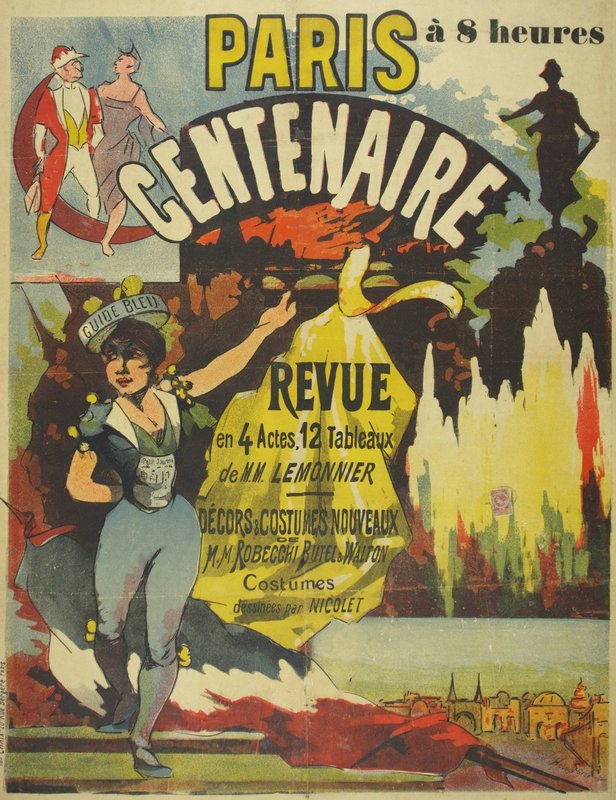

Backstage at the Paravent Chinois there is a poster for a revue celebrating the centenary of the 1789 revolution, which fits the precise chronology:

In the street are posters relating to the political movement around General Boulanger – for and against him - posters dating from the January 1889 elections, which also fits with an October 1889 date for the opening of the Moulin Rouge.

|

On the other hand, the first number on the opening night at the Moulin Rouge is a celebration of the Franco-Russian alliance, which would situate us in 1891 at the earliest, and is more likely in 1893, when the alliance was being formally celebrated, in France and in Russia. Danglard announces that Catherine the Great will be onstage to survey the troups of the Moulin Rouge, and he adds that if you object that she died almost 100 years ago, his reply would be that ‘at the Moulin Rouge we attach not the slightest importance to that kind of detail’.

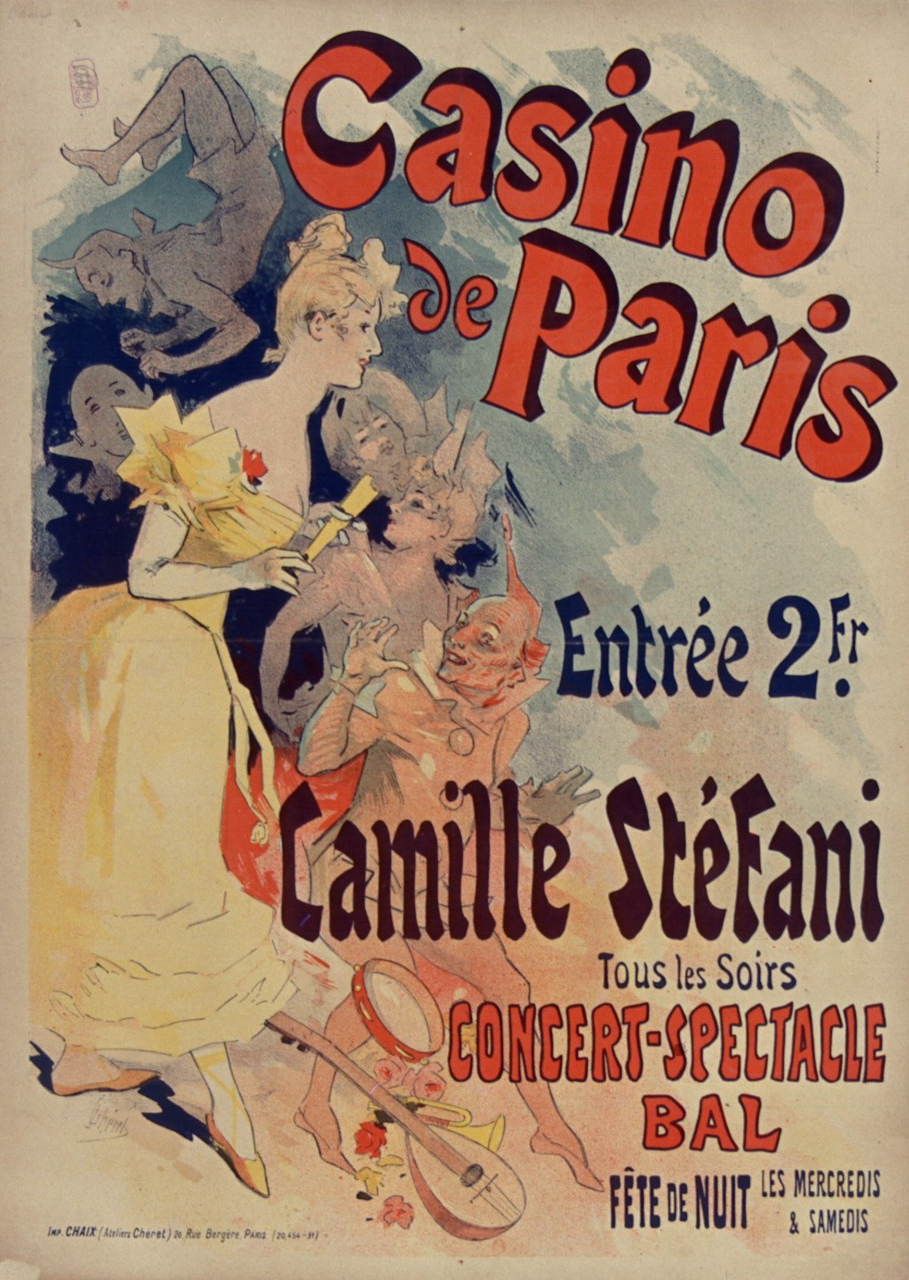

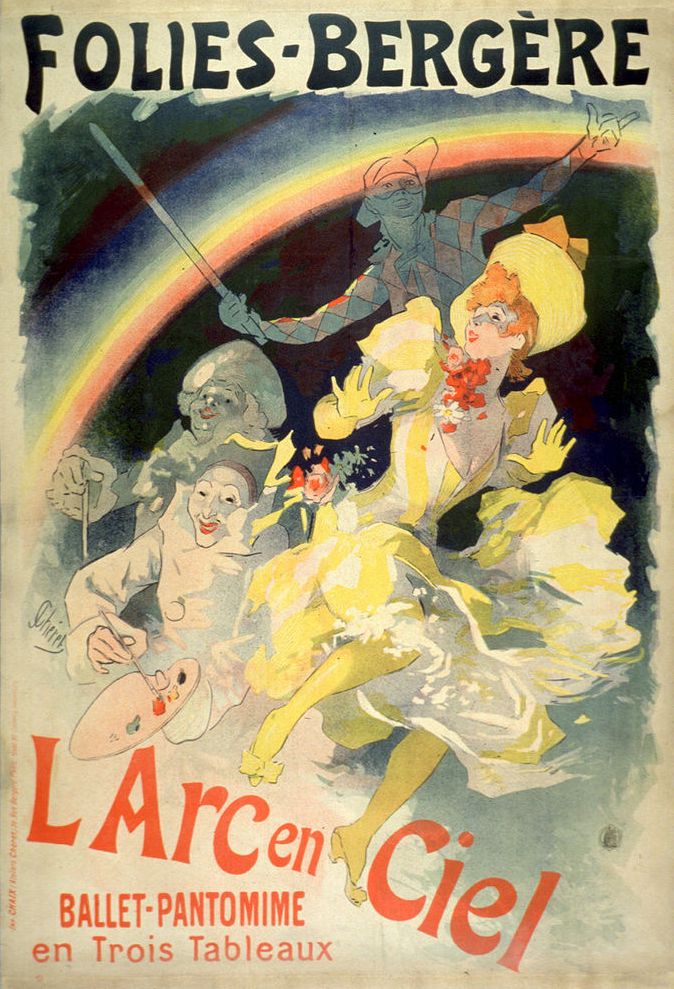

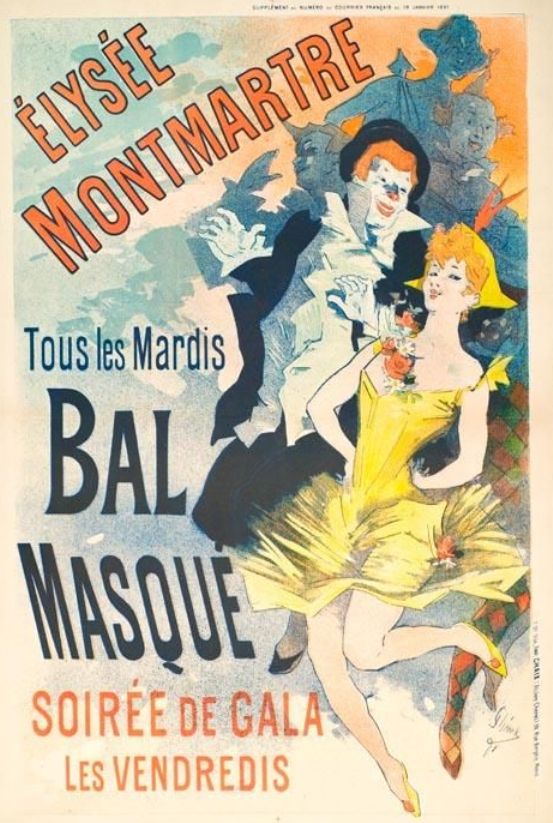

If the political and historical chronology is loose in its grasp of detail, the cultural chronology is even looser, above all in the iconography displayed. Posters for various cabarets and concert halls are shown, either in the credits or in the spaces of the narrative, and all of these date from after the creation of the Moulin Rouge in 1889. The two posters in the background when Nini and Alexandre are watching Paulus at the Petit Casino are by the master creator of posters in this period, Jules Cheret. Both date from 1891:

All of these posters seem to have been manipulated for the film, displacing or entirely changing the wording. There are other posters that seem to have been created for the film, or at least I haven't found period originals for those that can be seen in the background of these scenes:

|

The Moulin Rouge poster features a male figure dressed like the character Casimir, and the name on the Guibole poster is that of a character in the film, so they are clearly new creations.

The poster for the restaurant Maxim’s, whether it is a period original or created for the film, is an anachronism, since Maxim's was only called Maxim's from 1895 onwards. |

French Cancan's looseness with chronology fits the idea that this is not just a nostalgic film, but is a film about nostalgia, where exact details can become vague. The central idea – the revival of the Cancan – is itself premised on nostalgia. French Cancan, in 1954, is remembering a time some sixty years before, and remembering that then was being remembered a time some sixty years or so before that, when the cancan first became famous. French Cancan is a memory of a memory.

|

In its preoccupation with the past, French Cancan is certainly not thinking about politics, past or present. Boulangisme, one of the key historical reference points of right-wing politics in 1950s France, is a reference point for Renoir’s next film, Elena et les hommes (right), but it is hard to see the Boulangist posters carrying that political weight in French Cancan.

French Cancan was shot in 1954, the year the Algerian War of Independence began, but – again – it would be hard to find an allusion to the politics of that war in French Cancan. |

The opening performance in the film is given by La Belle Abbesse, whose name is a punning Europeanisation of the Algerian city Sidi Bel Abbès. When she says ‘Come with me to the Casbah’, this is not a reference to modern-day Algeria. It is a memory – a false memory, moreover – of a phrase attributed to Charles Boyer in the 1938 film Algiers. Boyer was originally chosen to play Danglars in French Cancan. It is at the same time a memory of his replacement, Jean Gabin, who was Pépé le Moko in the 1937 film by Duvivier of which Algiers was an exact English-language remake:

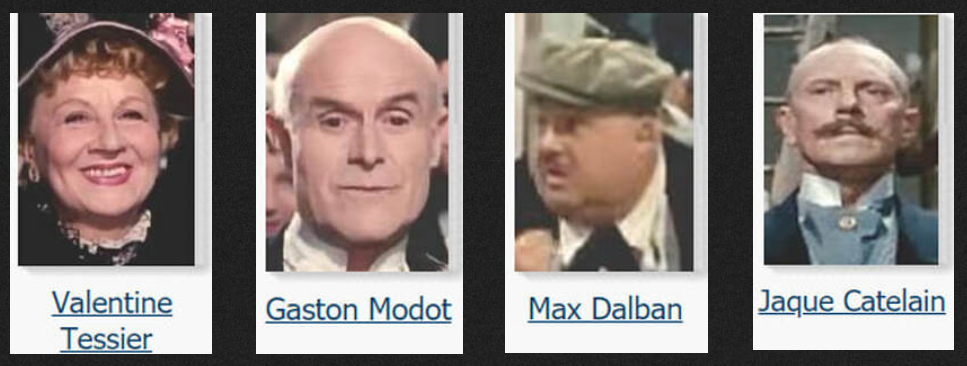

The phrase is a cine-memory, one of several that run through French Cancan, chiefly in the form of actors from Renoir’s past as a filmmaker: Gabin had been in three films by Renoir in the 1930s; Valentine Tessier, the star of his 1934 film Madame Bovary, plays Nini’s mother; Gaston Modot, who had been in La Grande Illusion and La Regle du jeu, is Danglard’s valet; Max Dalban, who had been eight Renoir films in the 1920s and '30s, plays the owner of La Reine Blanche; there is a small rôle for Jaque Catelain, who hadappeared in Renoir's 1938 film La Marseillaise but more than that had been a major leading man in French cinema of the 1920s, chiefly in films by Marcel L'Herbier:

I had thought that the most significant member of the cast in this respect was Madame Pâquerette, the actress who plays Mimi Prunelle, the former cancan star now become a tramp, a vestige of the past that in the 1890s Danglar is trying to revive:

All filmographies attribute to this Madame Pâquerette a career stretching back to c.1910, so that her presence in Renoir's film can seem like a fusion of nostalgia for bygone music-hall and nostalgia for bygone cinema. The sadness associated with her would also be a sadness at the lost childhood of cinema. However, extensive research (conducted after I introduced French Cancan at the NFT last September) makes it clear that this actress is not the Madame Pâquerette whose film career extends that far back (see my post here). The earliest of her rôles I can find are as a bystander in Duvivier's Un carnet de bal (1937) and a concierge in Moguy's Conflit (1938):

The peak of this Madame Pâquerette's career is in fact the 1950s and early '60s, with rôles in films by Jacques Becker, Jacques Tati, Henri Verneuil, Joshua Logan, Michel Deville and Louis Malle. Here she is in Zazie dans le métro (1960):

French Cancan is clearly a film about performance, about spectacle; like many of Renoir’s films about spectacle, like his preceding film Le Carrosse d’or for example, it is also an allegory of cinema.

I think this explains the film’s vagueness about chronology. Renoir nudges the opening of the Moulin Rouge forward from 1889, bringing it closer to a key date for himself, 1894, the year of his birth, and to a key date for everyone, 1895, the year of the birth of cinema.

In his autobiography, Les Mots, Sartre had said that he and cinema were contemporaries, born at the same time. That isn’t quite true for Sartre, born 1905, but it is true for Renoir.

He and cinema are the same age, and French Cancan is a film that evokes the moment before each is born, and also about what each will become: Danglard is Renoir, and the spectacle he creates from all those constitutent parts – décor, bodies, music - is not just the cinematograph – the inscription of movement - it is cinema.

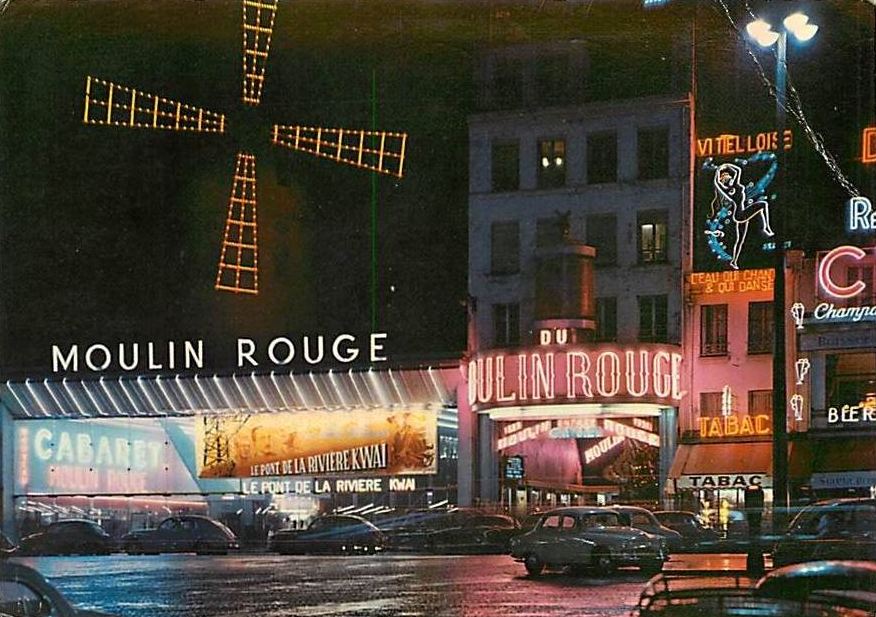

A point that would forcibly strike Parisian audiences in 1954 is that Danglard's creation, the Moulin Rouge music hall, had itself become a cinema: