|

an A to Z of Bande à part

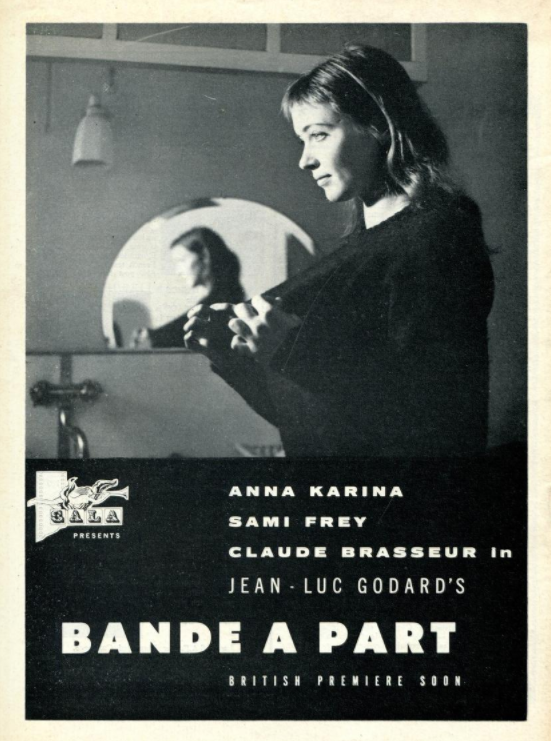

This post is a much-expanded and in places corrected version of a text written for the 2001 BFI theatrical and dvd release of Jean-Luc Godard's Bande à part (1964). The original flyer, designed by Secondary Modern, is reproduced far right. |

Godard wrote a three-page press release for the film in 1964 loaded with literary and filmic intertexts. The French text of this press release is reproduced at the end of this post.

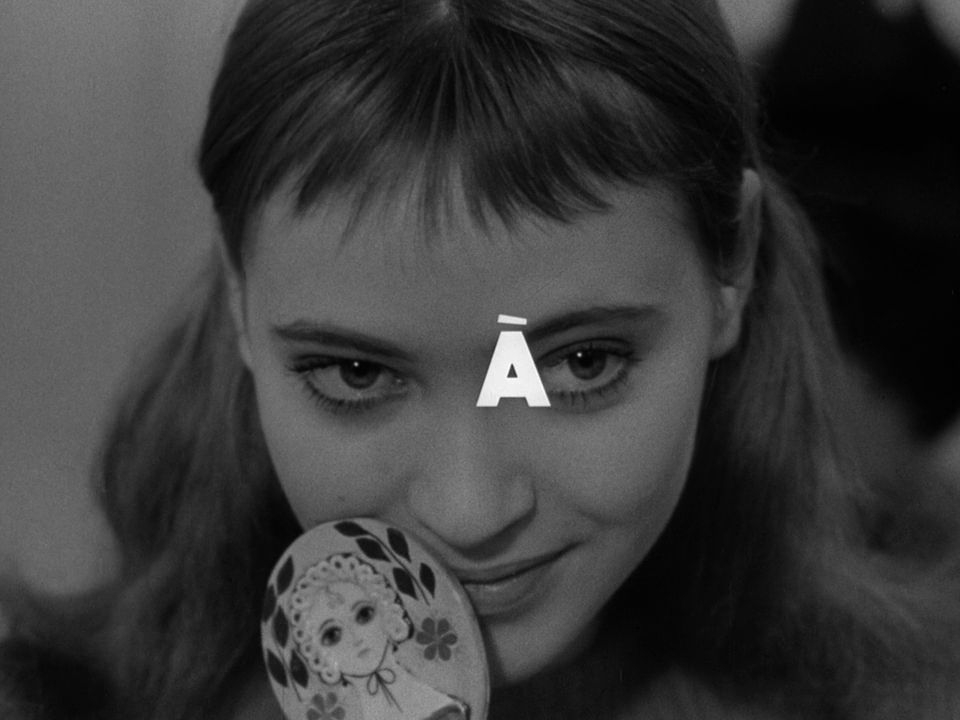

Anna

|

As Veronika (Le petit soldat), Angela (Une femme est une femme), Nana (Vivre sa vie), Odile (Bande à part), Natacha (Alphaville), Marianne (Pierrot le fou) or Paula (Made in USA), Karina is always Anna, the ‘New Wave Bride’, the model discovered, married and transformed into a star by Godard. He also made her an actress, in each of their seven films together drawing performances each time different and each time perfect. Her role in Bande à part is remarkable above all for the contrast with the three preceding films. The glamour evident in Le petit soldat (1960), Une femme est une femme (1961) and even in Vivre sa vie (1962) is played down. Her hairstyle is ridiculed, her face made plain, her body de-eroticised. When the narrator mentions Odile’s ‘peau douce’, her ‘soft skin’, he is just name dropping Truffaut’s latest film; when he mentions her romantic kisses, what we remember is the comical, tongue-out eyes-closed kiss she offers Arthur. To appreciate how romantic an image of Karina Godard could produce, see Alphaville, and the passionate embrace of Karina and Eddie Constantine, or their last work together, ‘Anticipation’, a short film about kissing. |

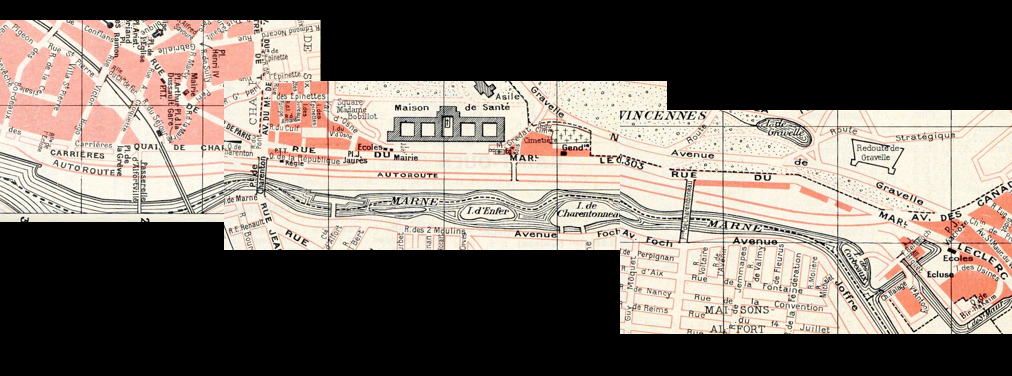

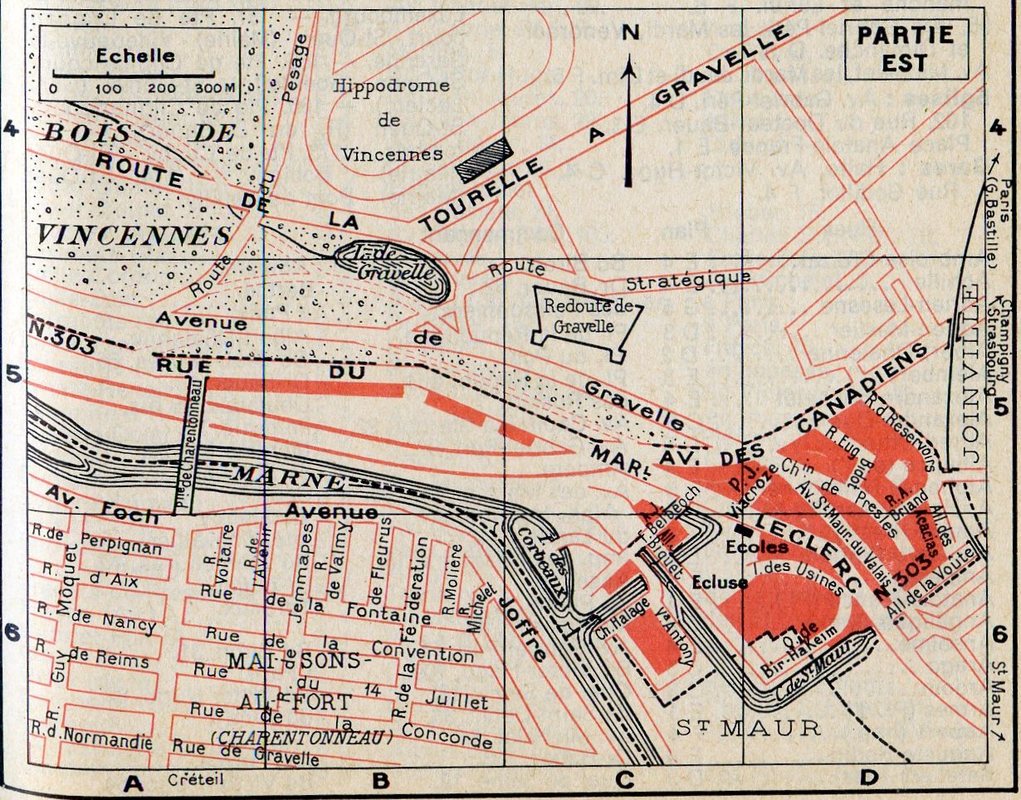

L'Autoroute de l'Est

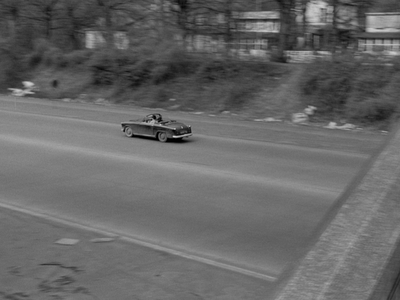

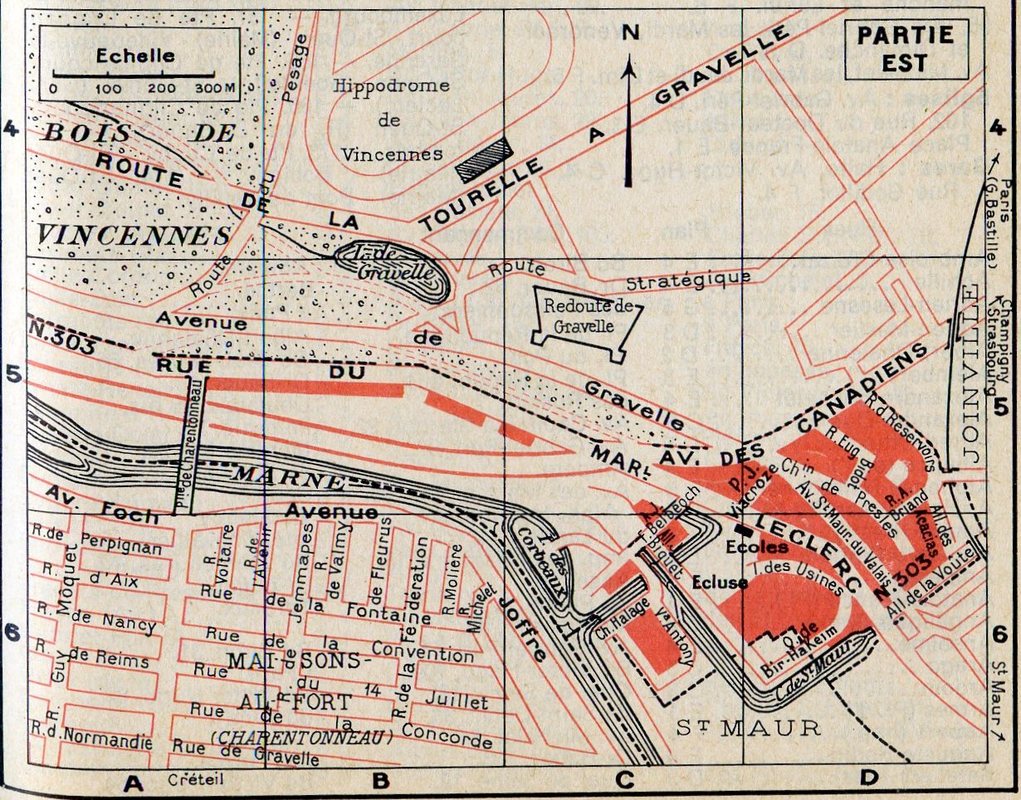

Although the motorway linking Paris with the East of France wasn't completed and opened until 1976, a small stretch of it existed in 1964 between Charenton-le-Pont and Joinville-le-Pont, running through Saint-Maurice:

This is the route by which Franz and Odile initially head back to Charenton, where they will meet Arthur at the 'Tout Va Bien' café, though they turn back on seeing Arthur's uncle's car coming the other way:

After the death of Arthur they leave again by this route:

They decide between going north or south and are then seen at the Porte d'Orléans, heading from the Avenue du General Leclerc:

They are heading south, towards the Autoroute du Sud.

|

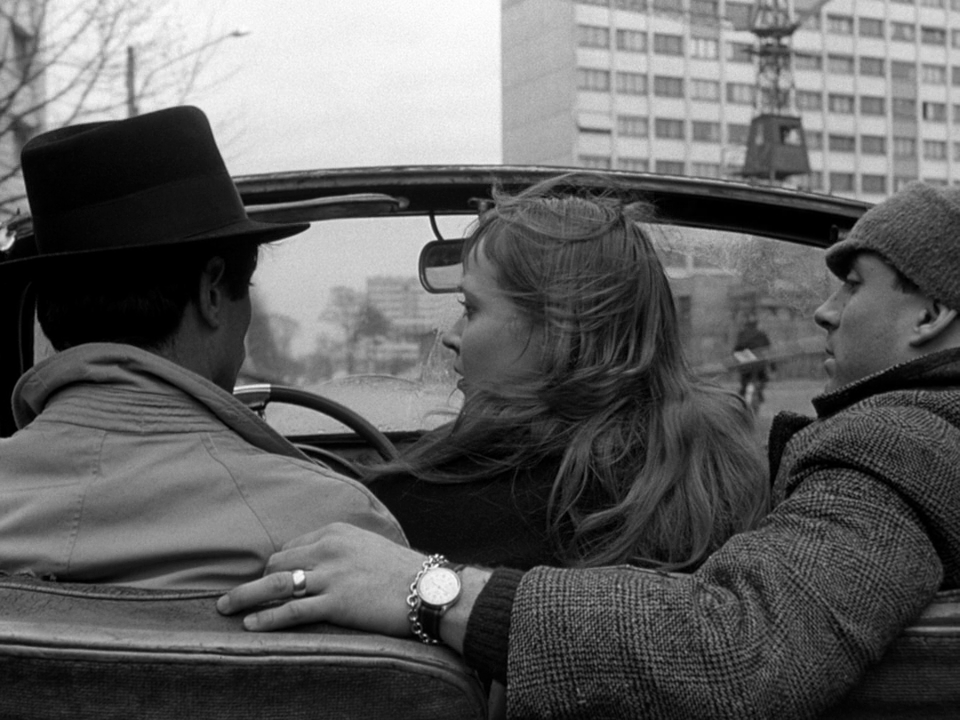

Bande à part (film)

It was originally announced as a film about ‘blousons noirs’ (leather jackets), hooligan adolescents, rockers on motorbikes. It developed into a study of three suburban misfits, the boys living out dreams of gangster cool and cowboy violence, the girl a kooky innocent with no idea what she wants. Each lives in their own world: even when they dance the Madison together, they are isolated, self-absorbed. They only ever form a ‘bande’ for the 24 seconds we see them running through the galleries of the Louvre. At the end, Franz and Odile form a couple, but that’s a different story. |

|

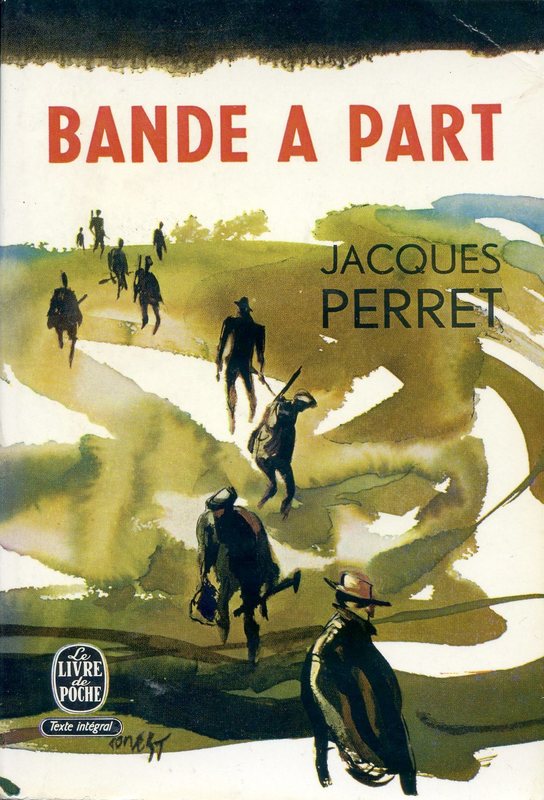

Bande à part (book)

Jacques Perret 's 1951 novel of the Resistance has nothing to do with Godard's film, though in a scene of La Peau douce Truffaut had Françoise Dorléac pick up a copy as a nod to Godard's film of the same year. This bookshop scene was cut from the final version of Truffaut's film. |

Banlieue

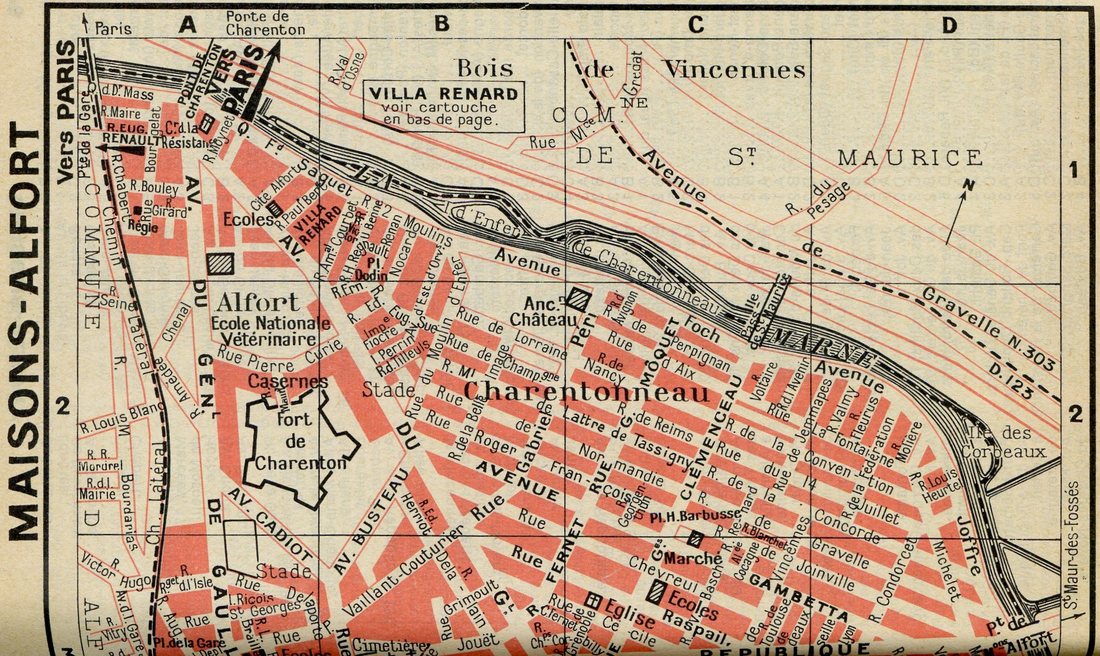

The action begins in the credit sequence, following a car as it crosses from Charenton-le-Pont into Maisons-Alfort and on to Saint Maurice:

The action begins in the credit sequence, following a car as it crosses from Charenton-le-Pont into Maisons-Alfort and on to Saint Maurice:

Franz and Arthur cross the Pont de Charenton (1A on the map above), turn left onto the Quai Fernand Saguet and continue through Maisons-Alfort alongside the Marne until just before the Pont de Maisons-Alfort (3D). Their journey is shown in five shots, with ellipses between them. The first shot goes from the Pont de Charenton to the Rue Ulysse Benne (1B); the second goes from just before the Avenue Georges Clemenceau (2C) to the Rue Voltaire; the third shows them passing Odile as she comes the other way, just before the Rue Molière; in the fourth they are on the stretch of the Avenue Joffre leading up to the Rue Condorcet.

The second time they make the journey, this time with Odile, the first shot covers slightly less distance than the first shot of the first journey, and this time the camera is in front of them, not behind. After the first cut the camera is behind them, reversing the order of the first journey. This time there is no ellipsis at the first cut, and in the shot that follows we get to see more of the Château Gaillard housing estate:

The location of the third shot of the second journey corresponds to that of the fourth of the first, with again the camera's position reversed. The second journey's last shot is the same as that of the first, except this time the car arrives and the camera pans to trace its path across the Pont de Maisons-Alfort and into Saint-Maurice:

The film refers to Joinville as the location of the house to be robbed, but the Villa Antony is in Saint Maurice (6C on the map below). It is not on the Ile des Corbeaux, as some sources sugggest:

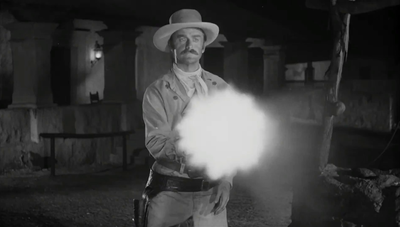

Billy the Kid

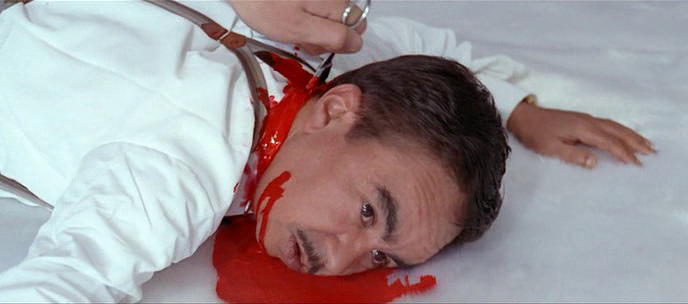

Arthur: ‘On the 13 July 1891, Billy the Kid was shot in the back by the Sheriff of Tombstone Pat Garrett...’. Arthur and Franz are as much suburban cowboys as smalltime gangsters, quick on the draw as they act out memories of Paul Newman in Penn’s The Left-Handed Gun. When Arthur is at last involved in a real duel in the sun, the reality is both more comic and more tragic than the screen memory.

Arthur: ‘On the 13 July 1891, Billy the Kid was shot in the back by the Sheriff of Tombstone Pat Garrett...’. Arthur and Franz are as much suburban cowboys as smalltime gangsters, quick on the draw as they act out memories of Paul Newman in Penn’s The Left-Handed Gun. When Arthur is at last involved in a real duel in the sun, the reality is both more comic and more tragic than the screen memory.

(Billy the Kid was actually shot on July 14 1881.)

Alain Bergala reports (Godard au travail, p.200) that Godard modelled the final shoot-out on the end of Sam Peckinpah's Ride the High Country (1962):

|

Brasseur

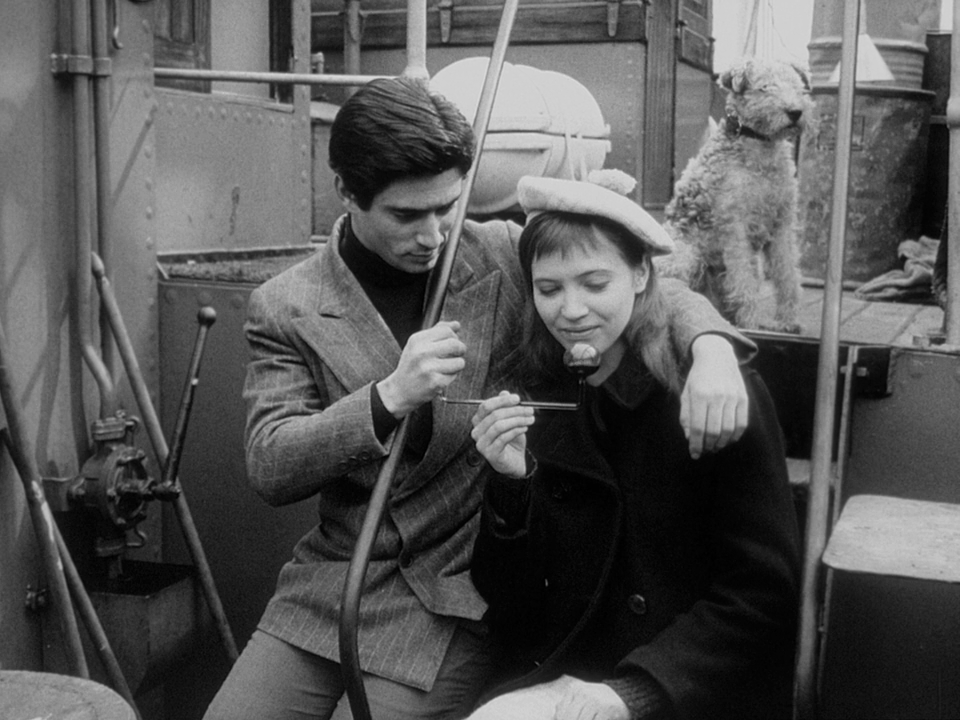

By the time they team up for Bande à part, Claude Brasseur and Karina know each other well, having worked together on Baratier’s 1963 comedy Dragées au poivre, for which they even recorded a duet together, ‘La vie s’envole’. The couple formed by the morose Arthur and the confused Odile is deliberately contrasted with the gaiety and sophistication of their previous performances. Twenty years later, in Détective, Godard will have Brasseur reprise the gloom of this performance in Bande à part. |

|

Brazil

When someone in a Godard film needs to get away, they head for the sun. Escape from the ennui of suburban Paris here means a boat for the tropics. At the end of Le petit soldat, the hero had hoped to take Karina to Brazil with him, but she dies. In Bande à part she survives to join Franz on the boat for Brazil, escaping to a world of Technicolor and CinemaScope. |

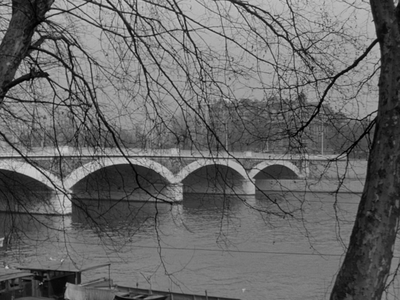

Bridges and Boats

If there are symbols in Bande à part, they are a part of the landscape: the pont des Arts, the pont du Carrousel, the pont d’Austerlitz, the bridges at the edge of Paris, crossing the Marne and the Seine, linking islands with the mainland. In this film they are memories of Rimbaud, ‘bridges suspended over impassive rivers’:

If there are symbols in Bande à part, they are a part of the landscape: the pont des Arts, the pont du Carrousel, the pont d’Austerlitz, the bridges at the edge of Paris, crossing the Marne and the Seine, linking islands with the mainland. In this film they are memories of Rimbaud, ‘bridges suspended over impassive rivers’:

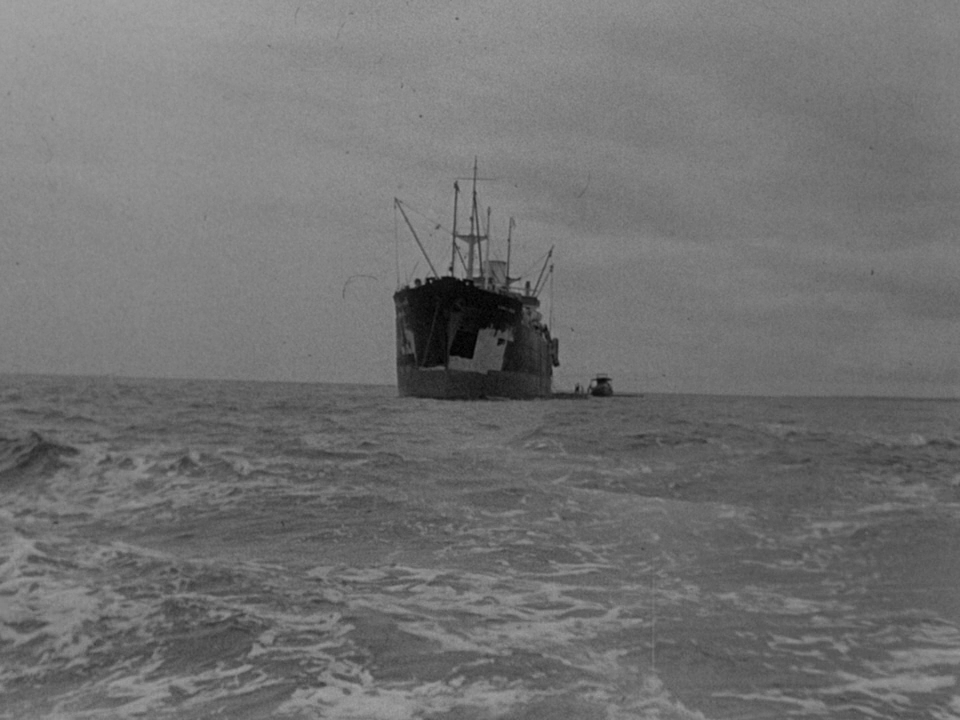

There are memories also of Rimbaud’s ‘Bateau ivre’, not so much the moored boat that helps Odile cross twelve feet of water, but the boat in which the hero of a Jack London story leaves to discover a new world, or the cargo ship in the last but one shot of the film, on which Odile and Franz sail away into the sunset:

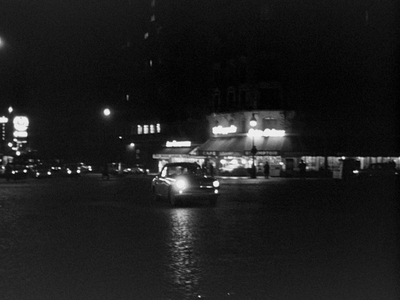

Cafés

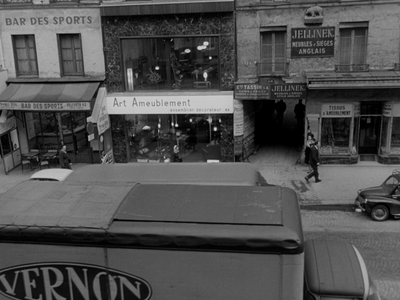

The café in a Godard film is always a defining location. In Bande à part, shots of the city at night show the brightly lit Café de la Paix on the Place de l’Opéra, but that's for bourgeois flâneurs who feel at home on the grands boulevards. Arthur and Odile do not go into the cafés they pass on the Boulevard de Clichy. Arthur and Franz avoid the dingy Café des Sports, next door to the language school. These outsiders live on the edge, arranging to meet at the Tout Va Bien, by the motorway exit, or hanging out at Le Vincennes in Vincennes, where the city meets the woods beyond. Here, when they dance with Odile, they take over the space, staking out their territory.

Chaplin

Film fans will recognise, says Godard, a reference to Chaplin’s The Immigrant in the last sequence of the film. It needed special treatment of the stock to get the quality of image right, strongly contrasted with the tones of the rest of the film. Earlier, Odile had enacted on a café table the dance of the bread loaves from The Gold Rush. These mentions are a reminder that it is not just the B-picture culture of Arthur and Franz that gives Bande à part its look.

Film fans will recognise, says Godard, a reference to Chaplin’s The Immigrant in the last sequence of the film. It needed special treatment of the stock to get the quality of image right, strongly contrasted with the tones of the rest of the film. Earlier, Odile had enacted on a café table the dance of the bread loaves from The Gold Rush. These mentions are a reminder that it is not just the B-picture culture of Arthur and Franz that gives Bande à part its look.

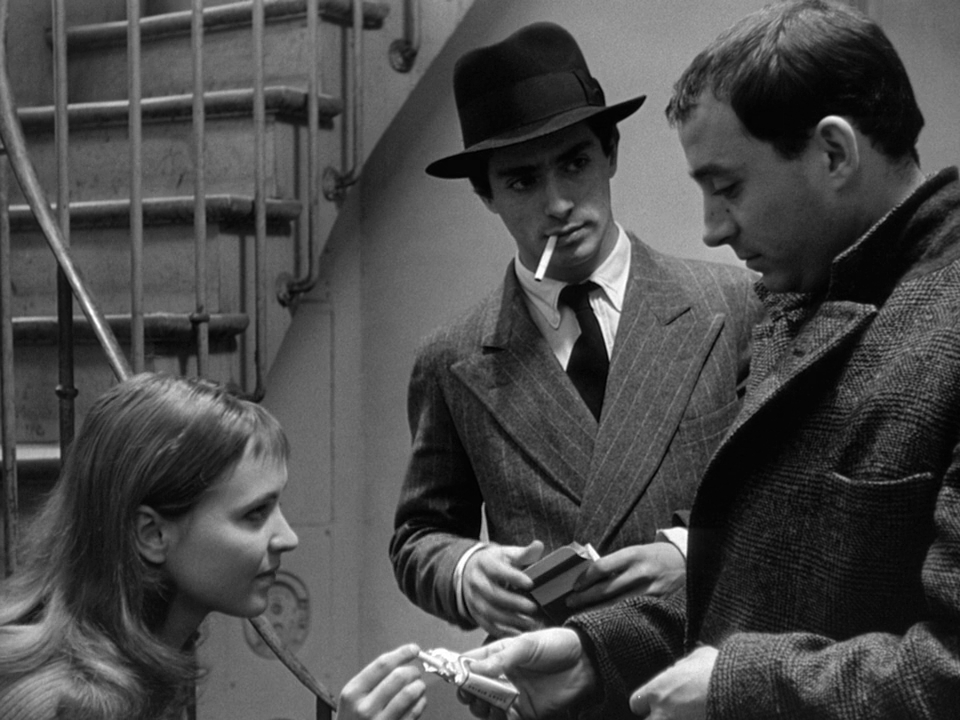

Cigarettes

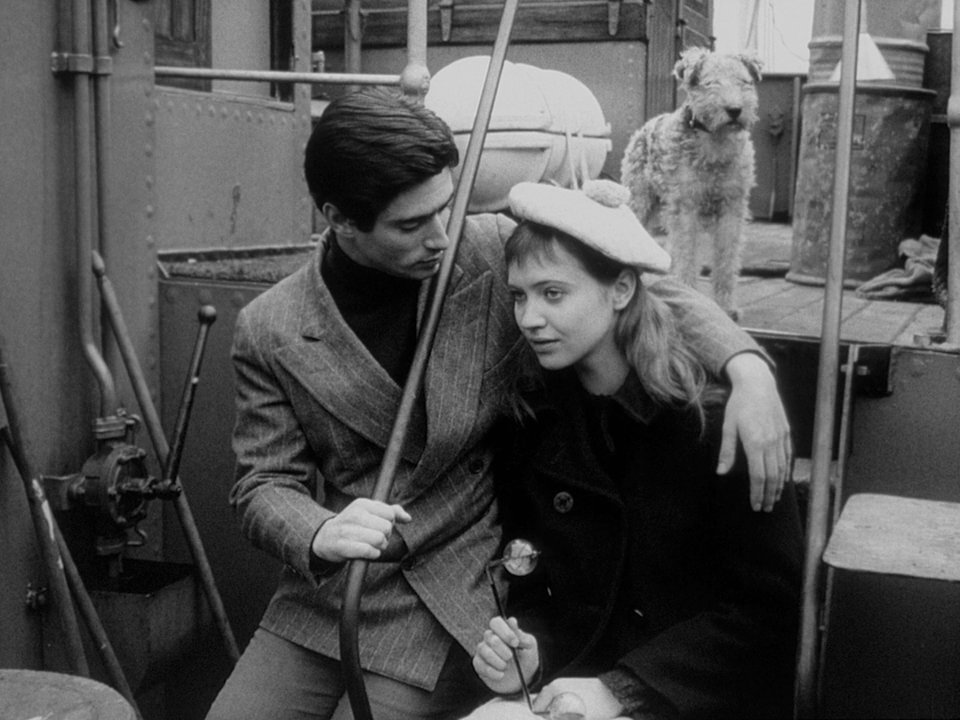

Odile refuses Franz's Gitanes and accepts Arthur's Lucky Strikes:

Odile refuses Franz's Gitanes and accepts Arthur's Lucky Strikes:

Cinemas

On the Rue du Faubourg Saint Antoine two cinemas are seen clearly, the Saint-Antoine, immediately opposite the language school, with John Sturges's Sergeants Three (1962) playing, and the Cinéphone at 100 Rue du Faubourg Saint Antoine:

On the Rue du Faubourg Saint Antoine two cinemas are seen clearly, the Saint-Antoine, immediately opposite the language school, with John Sturges's Sergeants Three (1962) playing, and the Cinéphone at 100 Rue du Faubourg Saint Antoine:

The film playing at the Cinéphone is Lewis Gilbert's Carve Her Name With Pride (1958), called in French Agent secret S.Z. The one name on the poster we can see - not coincidentally I would guess - is that of Maurice Ronet, who was Anna Karina's lover at the time.

Behind a van we can see the cinema La Bastille (5 Rue du Faubourg Saint Antoine) and a poster for a film starring Guy Madison and Michèle Mercier, which must be Le Prigioniere dell'isola del diavolo (1962). Later, when Arthur and Odile are walking around Paris at night, they pass the Pathé Wepler on the Boulevard de Clichy, with the 1964 Louis de Funès comedy Faites sauter la banque playing:

Behind a van we can see the cinema La Bastille (5 Rue du Faubourg Saint Antoine) and a poster for a film starring Guy Madison and Michèle Mercier, which must be Le Prigioniere dell'isola del diavolo (1962). Later, when Arthur and Odile are walking around Paris at night, they pass the Pathé Wepler on the Boulevard de Clichy, with the 1964 Louis de Funès comedy Faites sauter la banque playing:

Citations

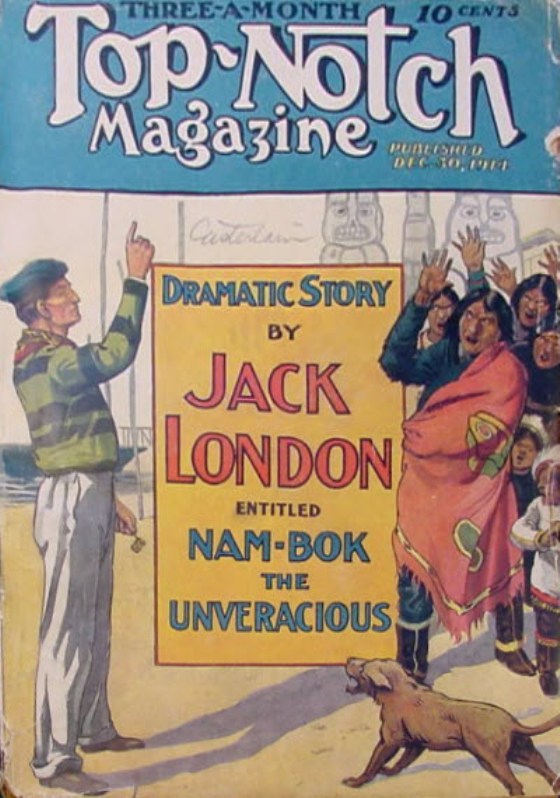

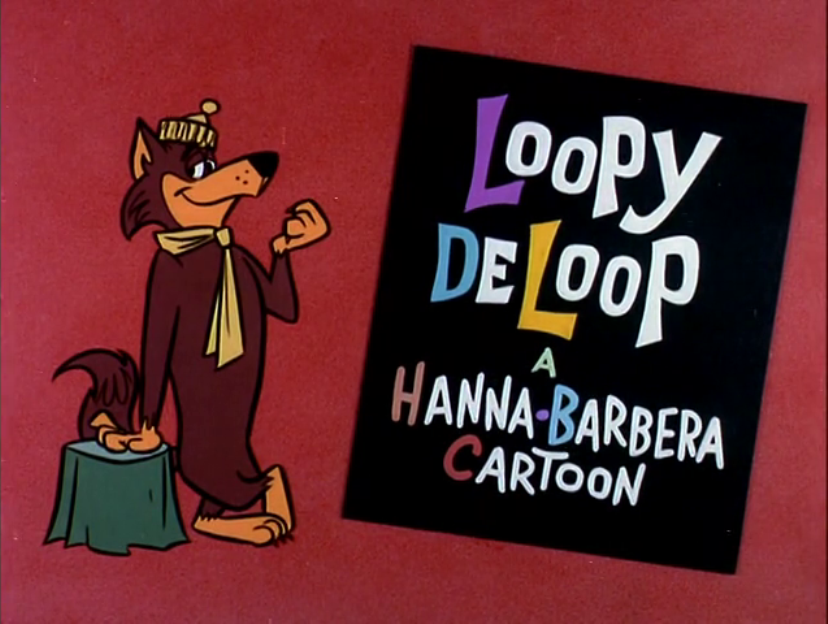

Aragon, Breton, Chabrol, Chaplin, David, Demy, T.S. Eliot, Ferrat, Hanna-Barbera, Jack London, Novalis, Poe, Queneau, Jean Renoir, Rimbaud, Shakespeare, Truffaut: the materials out of which Bande à part is woven. Godard might say what he said at Cannes of Eloge de l’amour, a film loaded with fragments from other authors: ‘There are no citations in this film.’

Aragon, Breton, Chabrol, Chaplin, David, Demy, T.S. Eliot, Ferrat, Hanna-Barbera, Jack London, Novalis, Poe, Queneau, Jean Renoir, Rimbaud, Shakespeare, Truffaut: the materials out of which Bande à part is woven. Godard might say what he said at Cannes of Eloge de l’amour, a film loaded with fragments from other authors: ‘There are no citations in this film.’

Clichy

The scenario describes the place where Franz has basketball practice as near the 'grands immeubles de la Porte Clichy':

The scenario describes the place where Franz has basketball practice as near the 'grands immeubles de la Porte Clichy':

This is the edge of the city, where Paris meets Clichy. Some of the surrounding buildings are still there, but the open space with the basketball court was soon after covered by the Boulevard périphérique:

Close-ups

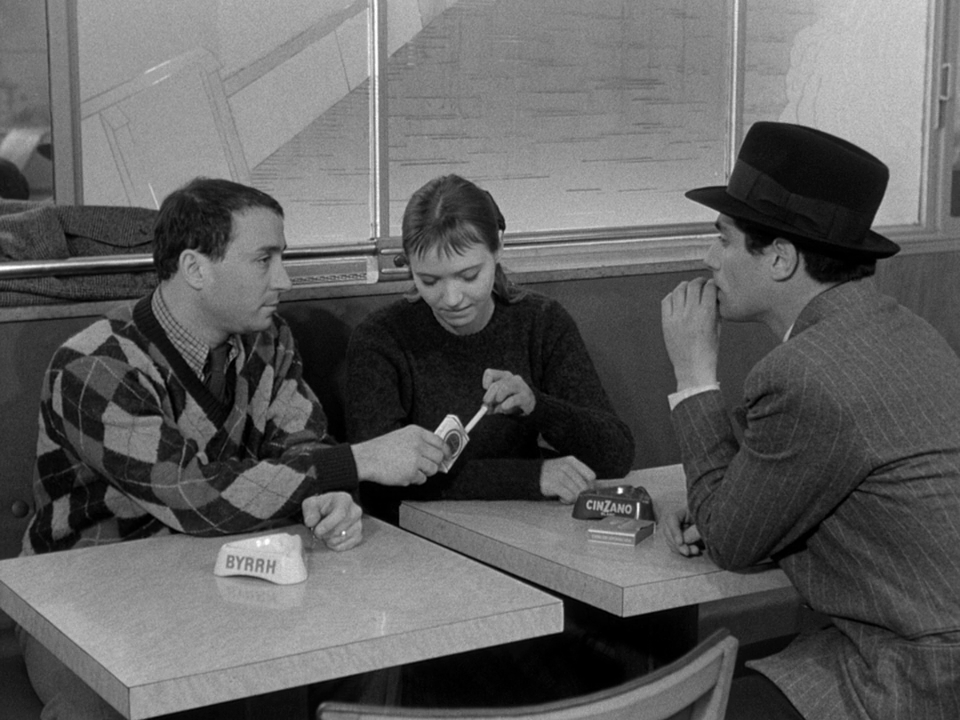

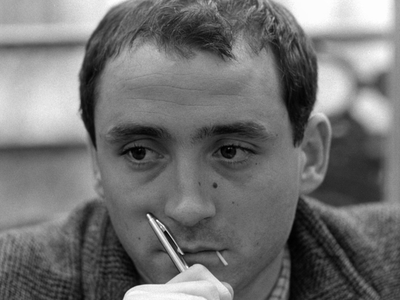

The close-ups in the credit sequence come from the English lesson scene:

The close-ups in the credit sequence come from the English lesson scene:

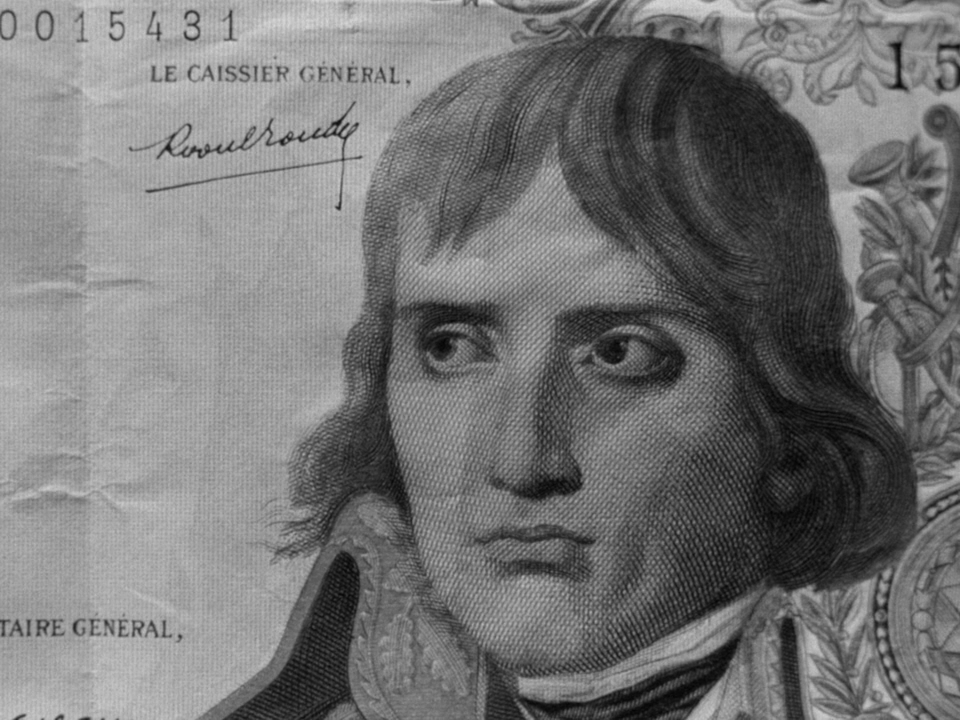

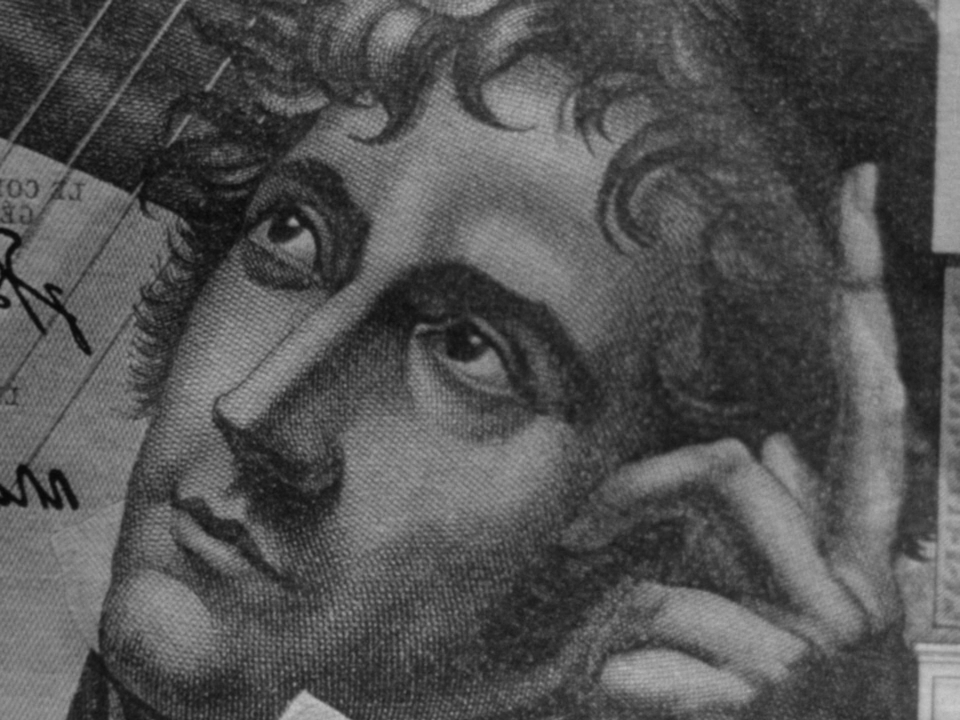

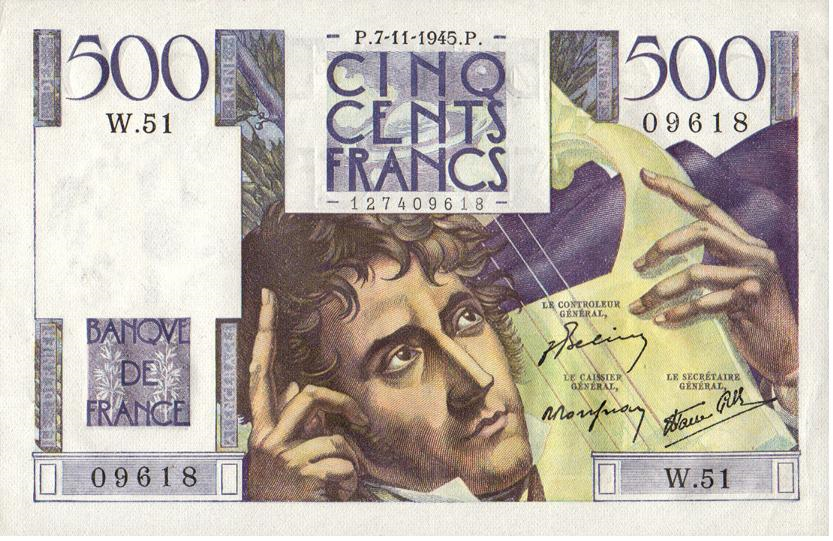

Those of Franz and Arthur are echoed by the close-ups of Napoleon and Chateaubriand on the banknotes Odile examines:

It is tempting to think of these portraits as analogues of Franz and Arthur, scrutinised by Odile as if she were deciding between them.

Oddly, the Chateaubriand banknote has been reversed:

Oddly, the Chateaubriand banknote has been reversed:

The Chateaubriand banknote was withdrawn in January 1963 so by the time in which the film is set a great deal of the money to be stolen was no longer legal tender.

Louisa Colpeyn

Louisa Colpeyn (1918-2015), who plays Odile's aunt, was in Antoine Bourseiller's 1963 production of Giraudoux's Pour Lucrèce in which Anna Karina (and, briefly, Godard) appeared. Her previous film was La Mort de Belle:

Louisa Colpeyn was the mother of Patrick Modiano.

(dis-)Continuity

A familiar device in Godard is to show consecutively two different views of the same action. Here are two examples from the opening sequence:

A familiar device in Godard is to show consecutively two different views of the same action. Here are two examples from the opening sequence:

This is a chronological discontinuity. There is a topographical discontinuity in the following sequence. Franz and Arthur turn into the Rue du Faubourg Saint Antoine from the Place de la Bastille and head east towards the language school. Two shots later they are coming down the Rue du Faubourg Saint Antoine from the opposite direction:

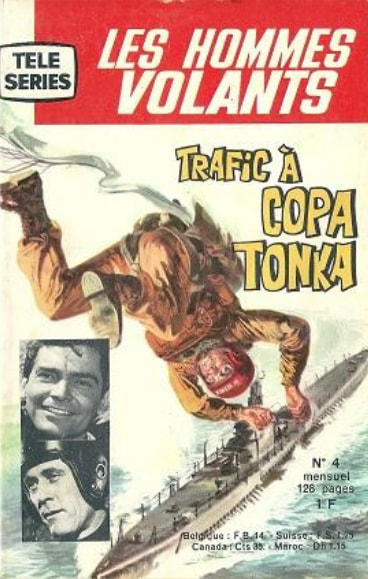

Copa Tonka

Franz's tastes are literary - Edgar Poe, Jack London, Raymond Queneau. Arthur prefers comic books:

Corot

The scenario begins thus: 'Paris, a mid-afternoon in February 1964, grey and misty, making the landscapes look like Corots.' Godard's narration in the film picks this up, saying that the Seine looked like a Corot as the camera takes in the river in slow panoramas:

The scenario begins thus: 'Paris, a mid-afternoon in February 1964, grey and misty, making the landscapes look like Corots.' Godard's narration in the film picks this up, saying that the Seine looked like a Corot as the camera takes in the river in slow panoramas:

Here are some of Corot's Paris views:

|

Coutard

‘My friend Raoul Coutard, France’s most brilliant cinematographer’, says the hero of Le petit soldat. Between 1959 and 1967, Godard’s friend shot all but one of his first fifteen features, and returned to shoot Passion and Prénom Carmen in the early '80s. He is the definitive New Wave cinematographer, working on most of Truffaut’s '60s films, and with Demy, Rouch and Marker. His work on Bande à part, reminiscent of A bout de souffle, is an unobtrusive tour de force, as far from the polarised black and white of Vivre sa vie as from the sumptuous primary colours of Le Mépris. Coutard’s palette of greys achieves a chromatic harmony that is part French cinéma-vérité, part on-the-streets American thriller. |

|

Crocodiles

‘Are there lions in Brazil? Yes, and there are crocodiles, Odile.’ A bad pun, stolen from Raymond Queneau’s novel Odile. The lions, of course, are there in the film with the tigers, caged up in the suburbs of Paris. (There aren't any lions in Brazil, and technically no crocodiles, only caimans.) |

Dance

People often dance in '60s films, often to comic effect (see Françoise Dorléac, twisting away on her own in Truffaut’s La Peau douce). The improvised Madison performed by Franz, Arthur and Odile, filmed in one three-minute take, is something different, an icon of '60s cool. This success is all the more remarkable because the dance is constantly interrupted by Godard’s voice, cutting out the music at will to comment on the characters’ thoughts and actions. This is, as Pauline Kael puts it, ‘the dance of sexual isolation’, used by Godard to give depth to characterisation, and also to demonstrate that the characters, even those who dream of freedom, are never free of montage. It is the puppetry of the editing suite.

People often dance in '60s films, often to comic effect (see Françoise Dorléac, twisting away on her own in Truffaut’s La Peau douce). The improvised Madison performed by Franz, Arthur and Odile, filmed in one three-minute take, is something different, an icon of '60s cool. This success is all the more remarkable because the dance is constantly interrupted by Godard’s voice, cutting out the music at will to comment on the characters’ thoughts and actions. This is, as Pauline Kael puts it, ‘the dance of sexual isolation’, used by Godard to give depth to characterisation, and also to demonstrate that the characters, even those who dream of freedom, are never free of montage. It is the puppetry of the editing suite.

For Pulp Fiction (1994), Tarantino remembered Hartley’s homage to Godard in Simple Men (1992), and showed Uma Thurman the dance scene from Bande à part to demonstrate that you don’t have to be a great dancer to do great dancing. This is exactly what all three scenes demonstrate.

Chantal Darget

Arthur's home at 18-20 rue de Patay, 13e, is that of Chantal Darget, who plays his aunt. She also appears in Masculin Féminin:

Chantal Darget was the wife of Antoine Bourseiller.

Michel Delahaye

Cahiers du Cinéma critic Michel Delahaye plays the doorman at the language school. His previous cameo appearance for Godard was in 'Il Mondo nuovo' (1963), his next would be in Alphaville (1965).

|

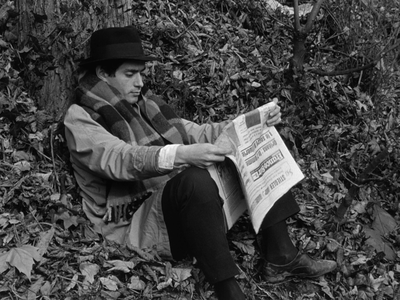

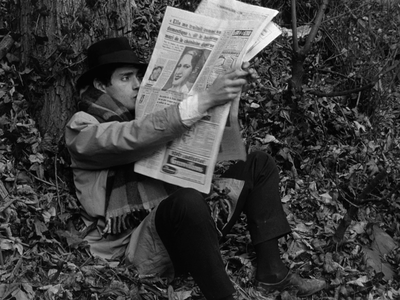

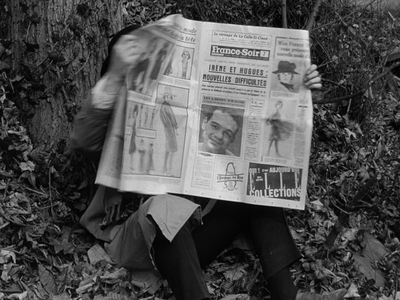

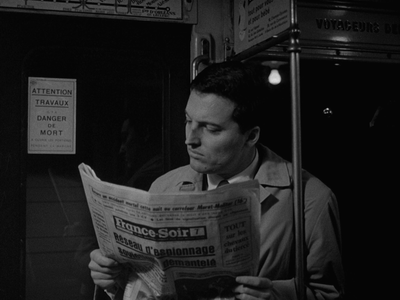

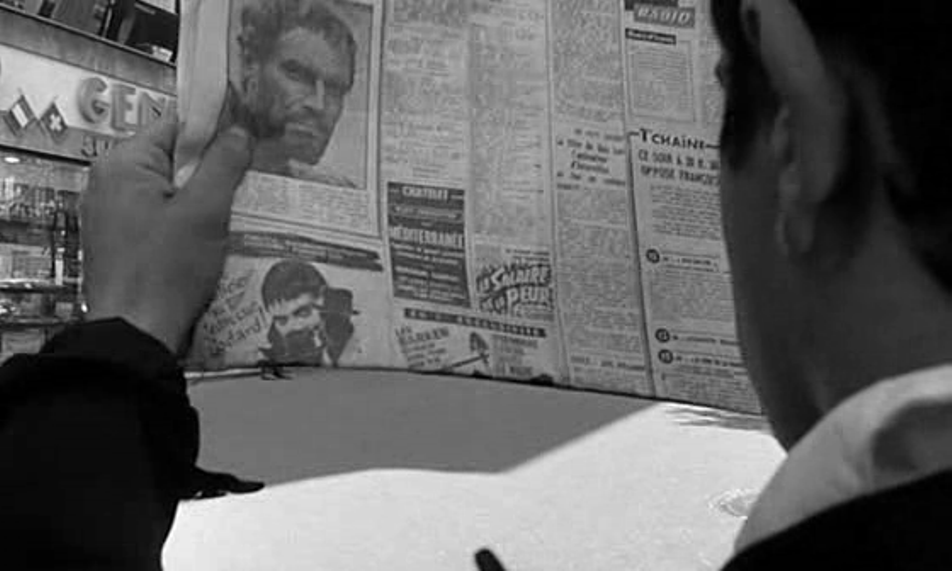

France-Soir

France-Soir is Godard's go-to source for the kind of quotidian banality invoked in Aragon's lyrics, set by Ferrat and sung by Karina. When Arthur and Franz read aloud stories from the newspaper, it is true, they also find there stories that border on the fantastic. Franz had read the story of the American who visited the Louvre in 9 minutes and 45 seconds in France-Soir. |

|

Sami Frey

Godard, Karina and Sami Frey all feature in Agnès Varda’s 1961 Les fiancés du Pont MacDonald, a comedy short based on the separation and reconciliation of Jean-Luc and Anna. Godard had planned to cast Frey and Karina together in a film of Giraudoux’s Pour Lucrèce, but the project fell through. Instead they made Bande à part. Godard identifies with Sami Frey. His ambition one day to cast him as Poe’s ‘William Wilson’, a man haunted by his double, says as much, as does the fact that Frey is given the mournful lines about love, loss and separation, and still ends up with the girl. |

Danièle Girard

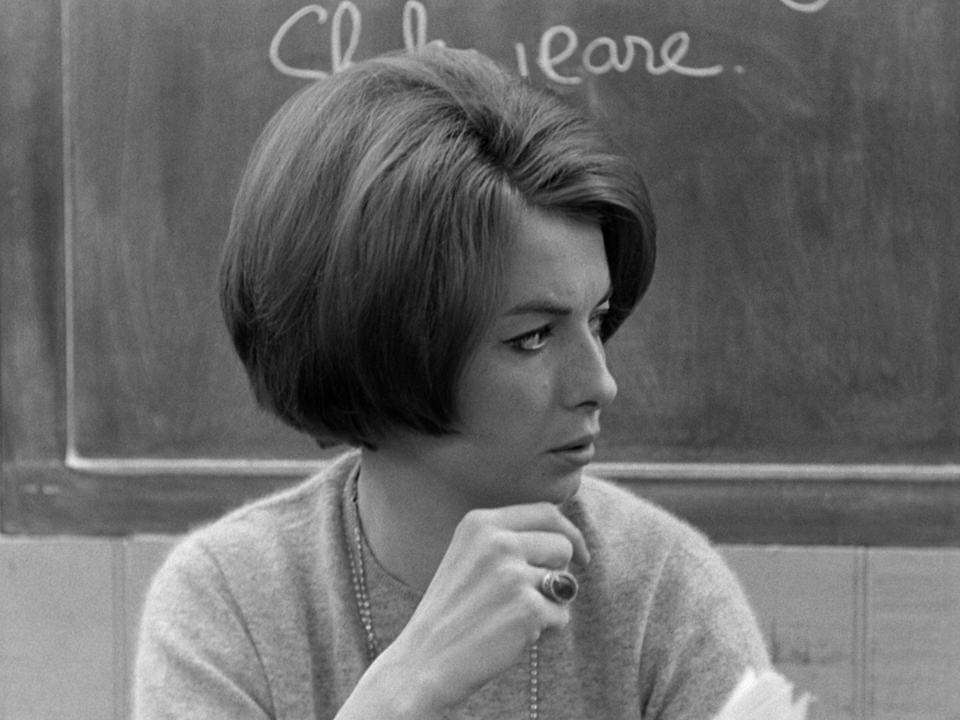

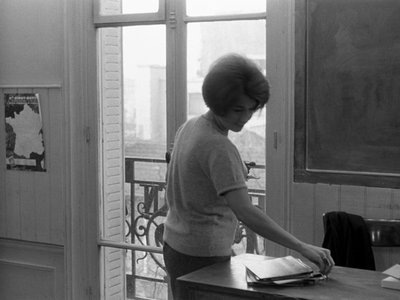

My big mistake in the original version of this A to Z was to identify the actress who plays the English teacher as Danièle Delorme (real name Danièle Girard), when it is actually the actress Danièle Girard. The former was a big star, the latter appeared in only a few films, including Truffaut's Domicile conjugal (1970). I also think she may be the uncredited taxi driver in Alphaville, but given my record I won't say that I'm sure:

My big mistake in the original version of this A to Z was to identify the actress who plays the English teacher as Danièle Delorme (real name Danièle Girard), when it is actually the actress Danièle Girard. The former was a big star, the latter appeared in only a few films, including Truffaut's Domicile conjugal (1970). I also think she may be the uncredited taxi driver in Alphaville, but given my record I won't say that I'm sure:

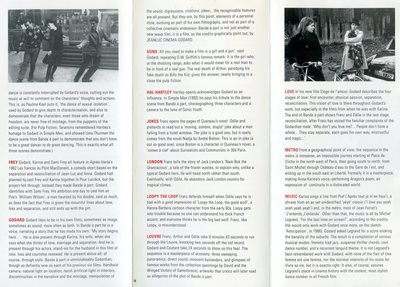

Godard

Godard likes to be in his own films, sometimes as image, sometimes as sound, more often as both. In Bande à part he is a voice, narrating a story he has made his own: ‘My story begins here…’. He is also present through Karina, his wife, when she says what she thinks about love, marriage and separation. And he is present through his actors, stand-ins for the husband in this film of love, loss and courtship renewed. He is present above all through style. Bande à part is unmistakeably Godardian, though as defiantly new as each of his previous six films. Handheld camera, natural light on location, harsh artificial light in interiors, discontinuities in the narrative and the montage, manipulation of the sound, digressions, citations, jokes… the recognisable features are all present. But they are, by this point, elements of a personal style, evolving as part of his own filmography, and not as part of a collective cinematic endeavour. Bande à part is not just another New Wave film, it is a film, as the credits graphically point out, by JEANLUC CINEMA GODARD.

Godard likes to be in his own films, sometimes as image, sometimes as sound, more often as both. In Bande à part he is a voice, narrating a story he has made his own: ‘My story begins here…’. He is also present through Karina, his wife, when she says what she thinks about love, marriage and separation. And he is present through his actors, stand-ins for the husband in this film of love, loss and courtship renewed. He is present above all through style. Bande à part is unmistakeably Godardian, though as defiantly new as each of his previous six films. Handheld camera, natural light on location, harsh artificial light in interiors, discontinuities in the narrative and the montage, manipulation of the sound, digressions, citations, jokes… the recognisable features are all present. But they are, by this point, elements of a personal style, evolving as part of his own filmography, and not as part of a collective cinematic endeavour. Bande à part is not just another New Wave film, it is a film, as the credits graphically point out, by JEANLUC CINEMA GODARD.

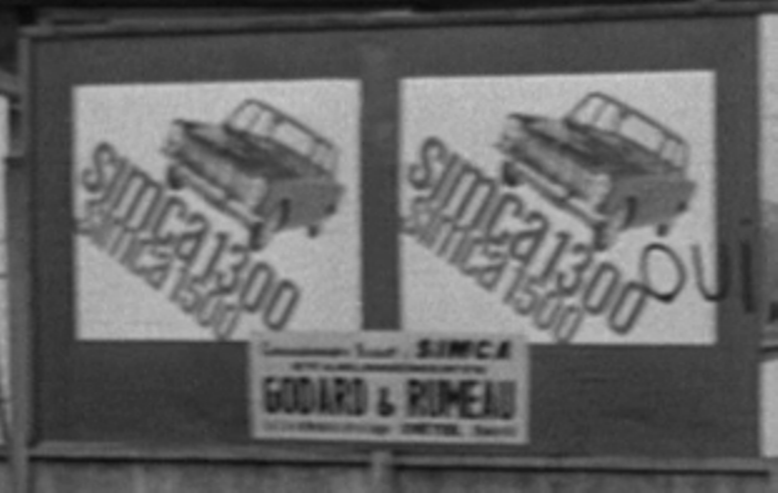

The name 'Godard' appears once more in the film: cycling in Maisons-Alfort, Odile passes a poster for the Créteil-based Simca concessionary Godard and Rumeau. This appearance of Godard's name coincides with the beginning of Godard's voice-over narration: ' My story begins here...'.

Guns

‘All you need to make a film is a girl and a gun’, says Godard, quoting D.W. Griffith’s famous remark (see here for a history of the phrase). It is the girl who, at the shooting range, asks what it would mean for a real man to be in front of a real gun. The real death of Arthur, parodying his fake death as Billy the Kid, gives the answer, neatly bringing to a close the pulp fiction.

‘All you need to make a film is a girl and a gun’, says Godard, quoting D.W. Griffith’s famous remark (see here for a history of the phrase). It is the girl who, at the shooting range, asks what it would mean for a real man to be in front of a real gun. The real death of Arthur, parodying his fake death as Billy the Kid, gives the answer, neatly bringing to a close the pulp fiction.

Hal Hartley

In Simple Men (1992) Hartley pays his tribute to the dance scene from Bande à part, choreographing three characters and a camera to Sonic Youth's Kool Thing:

In Simple Men (1992) Hartley pays his tribute to the dance scene from Bande à part, choreographing three characters and a camera to Sonic Youth's Kool Thing:

|

Jokes

Franz opens the pages of Raymond Queneau’s novel Odile and pretends to read out a ‘moving, sombre, stupid’ joke about a man falling from a hotel window. The joke is a good one, but it really comes from the novel Nadja by André Breton. This is a literary in-joke, since Breton is a character in Queneau’s novel, a ‘roman à clef’ about Surrealists and Communists in 1930s Paris. |

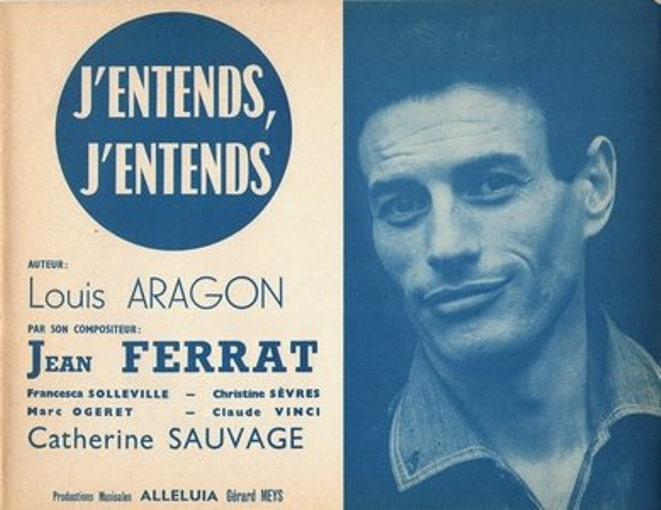

Michel Legrand

Karina sings a line from Piaf’s ‘Je t’ai dans la peau’ (‘Après tout je m’en fous’), a phrase from a ‘yéyé’ classic (‘I love you yeah yeah yeah yeah’) and, in the métro, most of Jean Ferrat’s ‘J’entends J’entends’ (his setting of the Aragon poem). Other than that, the music is all by Michel Legrand, ‘For the last time on screen?’, according to the credits. (He would only work with Godard once more, on the sketch ‘Anticipation’, in 1966). Godard asked Legrand for a score evoking the banality of the suburbs. The result is a compilation of various musical modes: frenetic trad jazz, suspense thriller chords, cool dance number, and a recurrent languid theme. It is not Legrand’s best remembered work with Godard, with none of the flair of Une femme est une femme, nor the minimal intensity of his score for Vivre sa vie, but it is exactly right. It also, of course, assures Legrand’s place in cinema history with the coolest, most stylish dance number in all French film.

Karina sings a line from Piaf’s ‘Je t’ai dans la peau’ (‘Après tout je m’en fous’), a phrase from a ‘yéyé’ classic (‘I love you yeah yeah yeah yeah’) and, in the métro, most of Jean Ferrat’s ‘J’entends J’entends’ (his setting of the Aragon poem). Other than that, the music is all by Michel Legrand, ‘For the last time on screen?’, according to the credits. (He would only work with Godard once more, on the sketch ‘Anticipation’, in 1966). Godard asked Legrand for a score evoking the banality of the suburbs. The result is a compilation of various musical modes: frenetic trad jazz, suspense thriller chords, cool dance number, and a recurrent languid theme. It is not Legrand’s best remembered work with Godard, with none of the flair of Une femme est une femme, nor the minimal intensity of his score for Vivre sa vie, but it is exactly right. It also, of course, assures Legrand’s place in cinema history with the coolest, most stylish dance number in all French film.

Loopy de Loop

Franz defends himself when Odile says he is bad with a good impression of ‘Loopy de Loop, the good wolf’, a Hanna-Barbera cartoon character from the early 1960s. Loopy gets into trouble because no one can understand his thick French accent and everyone thinks he is the big bad wolf. Franz, like Loopy, is misunderstood.

Franz defends himself when Odile says he is bad with a good impression of ‘Loopy de Loop, the good wolf’, a Hanna-Barbera cartoon character from the early 1960s. Loopy gets into trouble because no one can understand his thick French accent and everyone thinks he is the big bad wolf. Franz, like Loopy, is misunderstood.

LOUI'S COURS

The exterior, courtyard and staircase leading to the classroom are at 95 Rue du Faubourg Saint Antoine:

The classroom itself (see Baecque, Godard, p.840) was at the Remington secretarial school, 403bis Rue de Vaugirard:

Louvre

|

Franz, Arthur and Odile take 9 minutes 43 seconds to run through the Louvre, knocking two seconds off the old record. Godard and Coutard take 24 seconds to show us this feat. The sequence is a masterpiece of economy: three sweeping panoramics, direct sound, innocent bystanders, and glimpses of famous works from the collection (paintings by David and the Winged Victory of Samothrace) which critics will later read as allegories of the plot of Bande à part. The sequence was irritatingly imitated in Bertolucci's The Dreamers (2003).

|

Love

In Eloge de l’amour, Godard describes the four stages of love: first encounter, physical passion, separation, reconciliation. This vision of love is there throughout Godard’s work, but especially in the films from when he was with Karina. The end of Bande à part shows Franz and Odile in the last stage, after Franz has voiced the familiar complaints of the Godardian male: ‘Why don’t you love me?... People don’t form a whole... They stay separate, each goes his own way, mistrustful and tragic...’.

In Eloge de l’amour, Godard describes the four stages of love: first encounter, physical passion, separation, reconciliation. This vision of love is there throughout Godard’s work, but especially in the films from when he was with Karina. The end of Bande à part shows Franz and Odile in the last stage, after Franz has voiced the familiar complaints of the Godardian male: ‘Why don’t you love me?... People don’t form a whole... They stay separate, each goes his own way, mistrustful and tragic...’.

I have no idea what that love testing apparatus is.

Map

I think this man is consulting a map. I think I recognise this man, but I can't place him:

I think this man is consulting a map. I think I recognise this man, but I can't place him:

Other maps glimpsed in the film are not consulted:

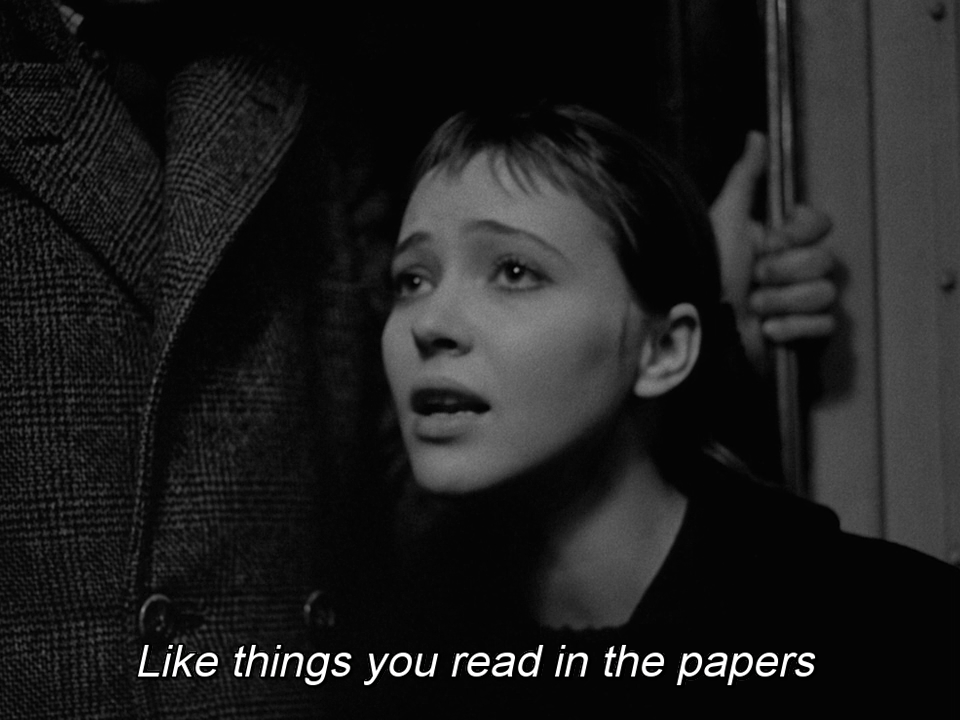

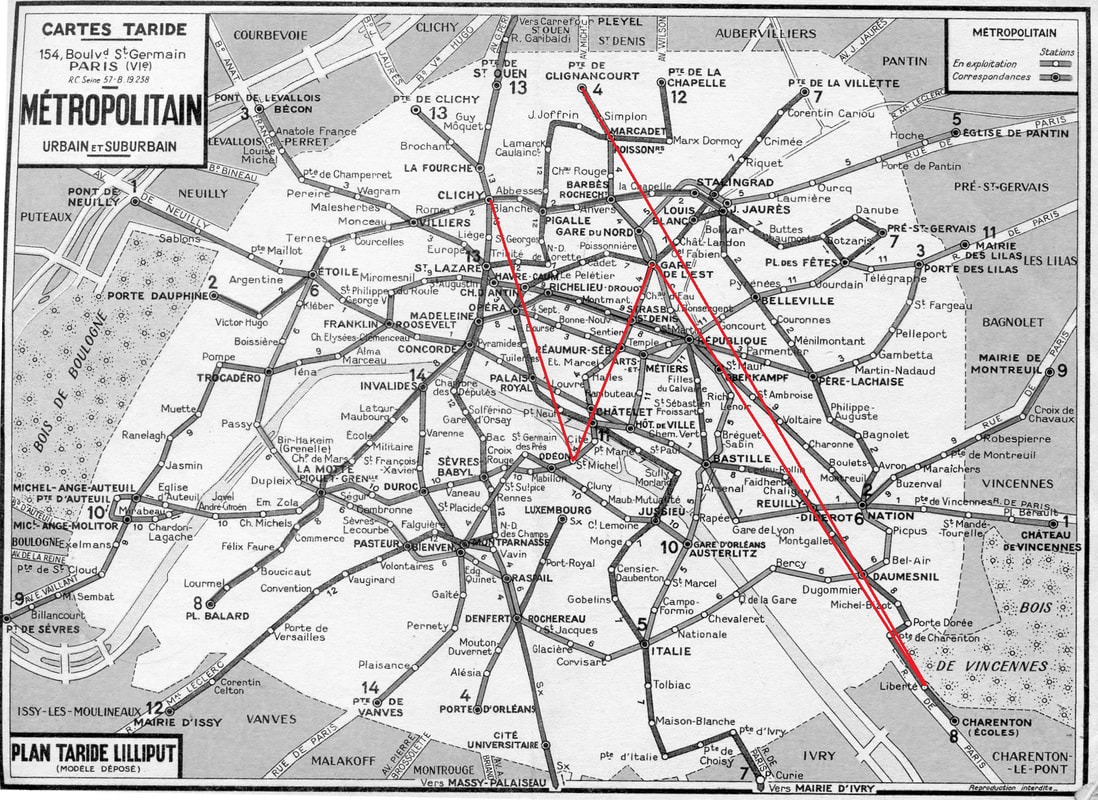

Métro

From a geographical point of view, the sequence in the métro is nonsense, an impossible journey starting at Place de Clichy in the north west of Paris, then going south to north, from Saint Michel through Château d’eau to the Gare de l’Est, then south east at Liberté before a final shot of a train at Porte de Clignancourt in the north, heading south. Formally it is a masterpiece, making Anna Karina’s voice, reciting Aragon’s poem, an expression of continuity in a dislocated world.

From a geographical point of view, the sequence in the métro is nonsense, an impossible journey starting at Place de Clichy in the north west of Paris, then going south to north, from Saint Michel through Château d’eau to the Gare de l’Est, then south east at Liberté before a final shot of a train at Porte de Clignancourt in the north, heading south. Formally it is a masterpiece, making Anna Karina’s voice, reciting Aragon’s poem, an expression of continuity in a dislocated world.

Mimi

After 'Arthur, Sammy et Anouchka', another working title for the film was 'Les Mimis'. On the way to Joinville, Franz and Arthur pass Odile on her bicycle, after which Arthur remarks: 'elle est mimi, cette môme'. Mimi, short for mignonne = cute. Later Odile says she doesn't like to go dancing at Mimi Pinson's (a dance hall on the Champs Elysées).

After 'Arthur, Sammy et Anouchka', another working title for the film was 'Les Mimis'. On the way to Joinville, Franz and Arthur pass Odile on her bicycle, after which Arthur remarks: 'elle est mimi, cette môme'. Mimi, short for mignonne = cute. Later Odile says she doesn't like to go dancing at Mimi Pinson's (a dance hall on the Champs Elysées).

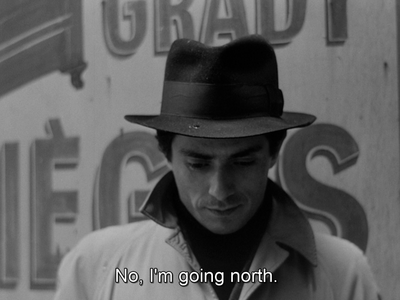

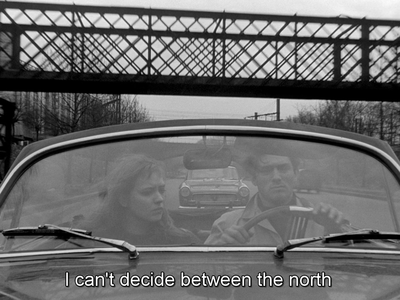

Nord-Sud

Escape is either to the North or to the South:

The doorman at the language school (Michel Delahaye) is reading Céline's 1960 novel Nord.

N.R.F.

|

Nouvelle Vague

Fifty minutes into Bande à part, the camera pans along the Boulevard de Clichy, past a quality clothes shop with a neon sign that reads ‘nouvelle vague’. This is a gag borrowed from Jean Eustache's 1963 short Du côté de Robinson (Les Mauvaises Fréquentations). The shop was still there, more than forty years later. In the next shot we a cinema showing Faites sauter la banque (‘Blow up the bank’) the latest comedy by the definitely ‘old wave’ Louis de Funès. |

By 1964, the New Wave was itself an old story: since 1959, its stylistic tics and famous names had become familiar, its revolutionary impact less evident; it had not engulfed the old school. New Wave directors were working with stars from the mainstream and New Wave stars were making films with the most conventional of directors. The New Wave was no longer a ‘bande à part’.

Odile - Karina

Godard's press release compares Karina as Odile to three literary heroines: Sarn from Mary Webb's Precious Bane, Ottilie (or Odile) from Goethe's Elective Affinities (1809) and Thomas Hardy's Tess of the d'Urbevilles (1892). He then compares her to four Hollywood actresses, Leslie Caron in Jean Renoir's play Orvet or in the film Lili, Cathy O'Donnell in They Live By Night, Jennifer Jones in Cluny Brown and Sylvia Sidney in You Only Live Once:

Odile Monod

Odile tells Arthur that her name is Odile Monod, which was the maiden name of Godard's mother. Arthur makes a pun on the surname and the name of a chain of shops, Monoprix. When Odile is arriving at the language school she passes a branch of Monoprix:

Odile tells Arthur that her name is Odile Monod, which was the maiden name of Godard's mother. Arthur makes a pun on the surname and the name of a chain of shops, Monoprix. When Odile is arriving at the language school she passes a branch of Monoprix:

Panoramas

Panoramic views via a panning camera are a recurrent motif in Bande à part. Most show something related to the action - the car in movement, mainly - but one such shot is used solely to mark the passage from one day to the next. This right-to-left panorama over Paris was taken from in front of the Sacré Coeur at Montmartre, a location of no topographical consequence for this film (or indeed, as far as I can remember, for any film by Godard):

Panoramic views via a panning camera are a recurrent motif in Bande à part. Most show something related to the action - the car in movement, mainly - but one such shot is used solely to mark the passage from one day to the next. This right-to-left panorama over Paris was taken from in front of the Sacré Coeur at Montmartre, a location of no topographical consequence for this film (or indeed, as far as I can remember, for any film by Godard):

Paris

‘Paris belongs to us’. The title of one of the first New Wave films, is a claim good for the New Wave as a whole and of Godard in particular. Bande à part is a Paris film, despite its principal location some two kilometres east of Paris, a house on the banks of the Marne: Arthur asks ‘Are we still in Paris?', Odile replies 'I don’t know’. This is somehow still Paris, because a part of the city is what we find beyond its limits, the strange suburban mix of factories and luxury villas, motorways and river islands, waste land and landscaped gardens. In contrast, the Rue du Faubourg Saint Antoine, the other main location, is real Paris, once the hotbed of revolutionary fervour, now a district of tacky repro furniture shops, dingy cafés, supermarkets and small businesses like the language school attended by Odile, Franz and Arthur. It is drab and unromantic, a place where people come to work, shop or study, but not for pleasure.

‘Paris belongs to us’. The title of one of the first New Wave films, is a claim good for the New Wave as a whole and of Godard in particular. Bande à part is a Paris film, despite its principal location some two kilometres east of Paris, a house on the banks of the Marne: Arthur asks ‘Are we still in Paris?', Odile replies 'I don’t know’. This is somehow still Paris, because a part of the city is what we find beyond its limits, the strange suburban mix of factories and luxury villas, motorways and river islands, waste land and landscaped gardens. In contrast, the Rue du Faubourg Saint Antoine, the other main location, is real Paris, once the hotbed of revolutionary fervour, now a district of tacky repro furniture shops, dingy cafés, supermarkets and small businesses like the language school attended by Odile, Franz and Arthur. It is drab and unromantic, a place where people come to work, shop or study, but not for pleasure.

Other parts of Paris we see in fragments. Franz drives around, past the Opéra and along the Boulevard des Capucines, sad and alone; Odile and Arthur wander up the Boulevard de Clichy before going down into the metro, and are barely less sad or alone. Inserts unconnected to the narrative sustain this motif of solitude:

An interlude before the final act shows the Seine and the Louvre as respite from the bleak B-picture mood:

This sequence includes the joyful dash through the Louvre, but it also includes Franz's reading of a 'moving, stupid and sombre story' from the book he has just bought.

Piaf

Karina speaks a line from Edith Piaf's song 'Je t'ai dans la peau' - 'Après tout je m'en fous...' (After all I don't give a fuck') - and is told off by Franz for using a vulgar expression. In the immediately preceding shot she had already said 'Après tout' and Godard in his narration also says it.

Karina speaks a line from Edith Piaf's song 'Je t'ai dans la peau' - 'Après tout je m'en fous...' (After all I don't give a fuck') - and is told off by Franz for using a vulgar expression. In the immediately preceding shot she had already said 'Après tout' and Godard in his narration also says it.

Poe

Godard's narration describes the setting of the house they plan to rob in words adapted from Edgar Allan Poe's 'Descent Into the Maelstrom' (as translated by Baudelaire):

Godard's narration describes the setting of the house they plan to rob in words adapted from Edgar Allan Poe's 'Descent Into the Maelstrom' (as translated by Baudelaire):

|

|

Je regardais vertigineusement, et je vis une grande étendue de l'océan, dont les eaux portaient une teinte de façon inky à amener à la fois à mon esprit le compte du géographe nubien de la Mare Tenebrarum. Un panorama plus effroyablement désolé aucune imagination humaine ne peut concevoir.A droite et à gauche, aussi loin que l'œil pouvait atteindre, s'allongeaient, comme les remparts du monde, les lignes d'une falaise horriblement noire et surplombante. I looked dizzily, and beheld a wide expanse of ocean, whose waters wore so inky a hue as to bring at once to my mind the Nubian geographer's account of the Mare Tenebrarum. A panorama more deplorably desolate no human imagination can conceive. To the right and left, as far as the eye could reach, there lay outstretched, like ramparts of the world, lines of horridly black and beetling cliff. |

|

Later, Franz remembers, vaguely, the plot of Poe’s ‘The Purloined Letter’, and later still there is a strong memory of ‘The Oval Portrait’ and a link with the end of Vivre sa vie made through an explicit motif: the two oval mirrors in which Karina inspects herself, and the oval portrait of a woman not unlike her that Arthur finds and shows to Franz. |

|

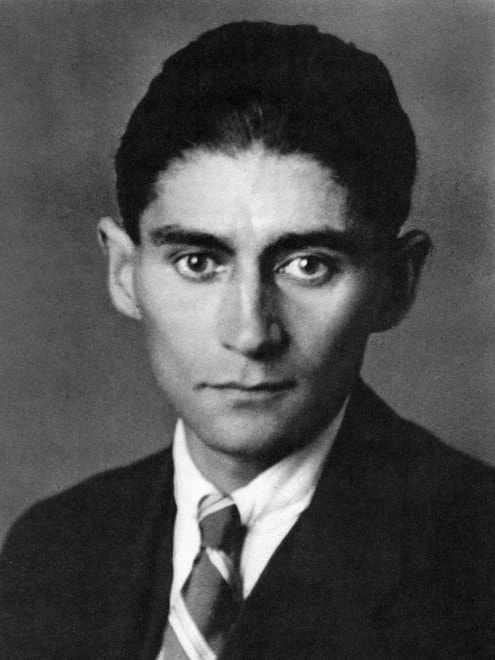

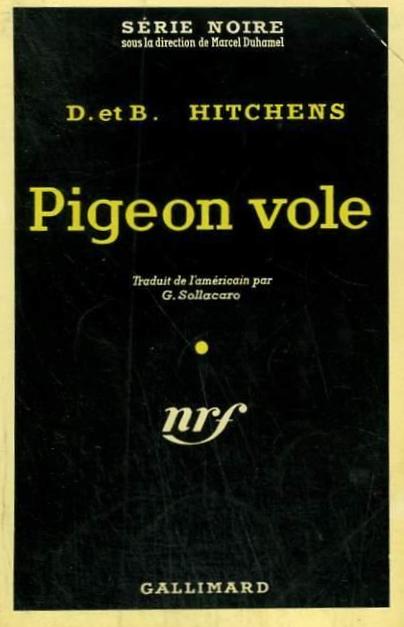

Plot

There are two plots in Bande à part, the crime story and the love story, the robbery that goes wrong and the romance that comes right. Both derive more or less from Fools’ Gold (1958) by Dolores Hitchens, published in French in the NRF pulp fiction collection ‘Série noire’ (with the strange modification of her name as 'D. et. B. Hitchens'). The novel was recommended to Godard by Truffaut. Godard transposes the setting from Pasadena to Paris, and changes almost all the names: Skip becomes Arthur, surname Rimbaud; Eddie becomes Franz (Sami Frey), surname Kafka; Karen becomes Odile, surname Monod (after Godard’s mother). As in Truffaut’s adaptation of David Goodis’s Down There (Tirez sur le pianiste), the bleak atmosphere of the pulp original is lightened, though Godard goes further by inventing a happy end. |

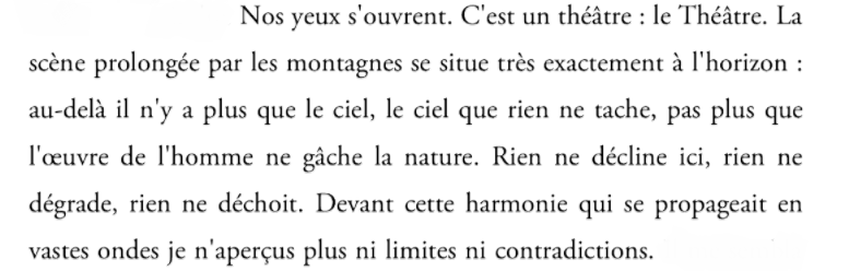

In Fools’ Gold the aunt really does die, Mr Stolz is arrested as a kidnapper (that’s where his money comes from), Skip is brutally gunned down by the police, and the lovers give themselves up, no doubt to face prison. The mood of the novel is fixed by Stolz’s closing words: ‘ruin and death’. Bande à part, on the other hand, sees the happy lovers leaving for a new life in Brazil, with the narrator announcing that ‘my story ends here, like a cheap novel, at that proud moment of existence where nothing declines, nothing decays, nothing falls, and it will be in another film, in Cinemascope and Technicolor, that you will learn of the adventures of Odile and Franz in the tropics.’

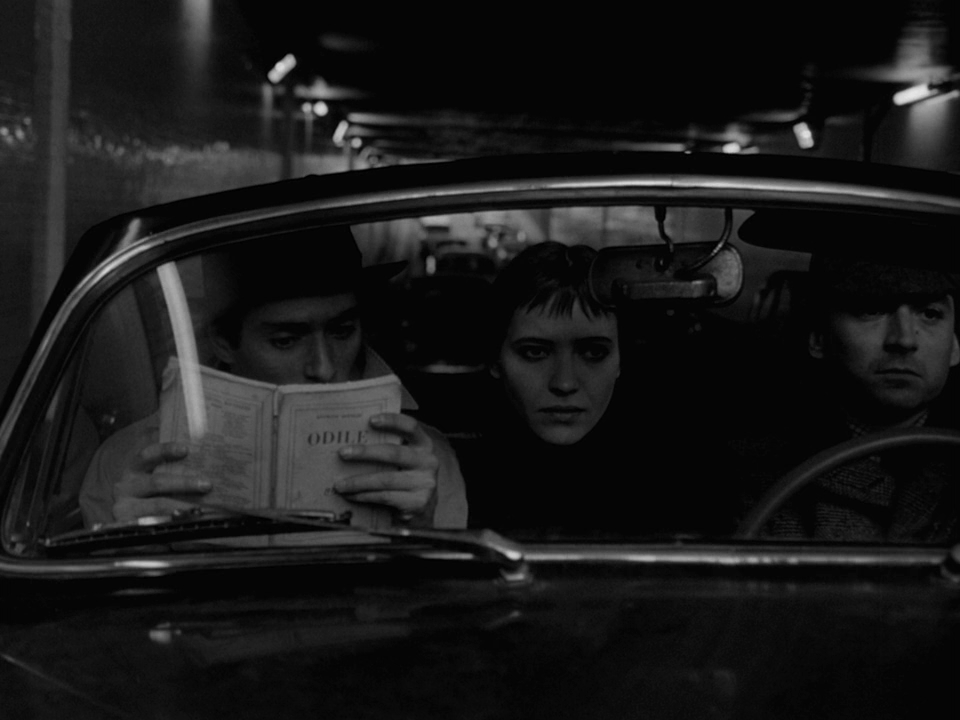

Queneau

Odile reminds Franz of a girl in a book, Odile, by Raymond Queneau. She is reading the book as the first robbery attempt is made. If she finished it she might recognise not only the ‘crocodile’ joke on her own name, but also the narrator’s closing words, also taken from Queneau’s novel.

Odile reminds Franz of a girl in a book, Odile, by Raymond Queneau. She is reading the book as the first robbery attempt is made. If she finished it she might recognise not only the ‘crocodile’ joke on her own name, but also the narrator’s closing words, also taken from Queneau’s novel.

|

Racing - Monaco

Arthur reads in the paper of Racing Club de France's victory over Monaco by five goals to two. This appears to be wishful thinking, since in the only match they had played so far that season, in October 1963, Monaco won five-three. The return fixture was due to be played on March 26th 1964, a week after the end of the Bande à part shoot, so Racing's revenge is a guess. (In fact, Monaco won five-one.) |

Rimbaud

'Des ciels gris de cristal'; 'je descendais des fleuves impassibles'; 'rien ne bougeait encore au front des palais'; 'l'eau était morte'; 'un goût de cendre vole dans l'air'. Fragments of poems by Rimbaud turn up in the narration, but the poet is also present as Arthur, surname Rimbaud, a name given perhaps because he likes guns, or because life disgusts him, or because, through his B-picture fantasies, he is ‘an other’, 'un autre’.

'Des ciels gris de cristal'; 'je descendais des fleuves impassibles'; 'rien ne bougeait encore au front des palais'; 'l'eau était morte'; 'un goût de cendre vole dans l'air'. Fragments of poems by Rimbaud turn up in the narration, but the poet is also present as Arthur, surname Rimbaud, a name given perhaps because he likes guns, or because life disgusts him, or because, through his B-picture fantasies, he is ‘an other’, 'un autre’.

Rwanda

When Arthur and Franz read out items from the newspapers, these stories of theft and murder in everyday France give their own crimes a context. This, with the shots of Paris street life, is as sociological as the film gets. Unusually, even for this period of Godard’s filmmaking, there is hardly any politics in Bande à part. The story of the massacre of Tutsis by Hutus in Rwanda, even if it mentions Peking, is a transformation of international politics into the stuff of myth: ‘The Hutus are sawing the legs off the giant Tutsis, their former masters, to turn them into ordinary men... The seven foot high king is forced to flee... Peking supports the Kingdom of Giants...’.

When Arthur and Franz read out items from the newspapers, these stories of theft and murder in everyday France give their own crimes a context. This, with the shots of Paris street life, is as sociological as the film gets. Unusually, even for this period of Godard’s filmmaking, there is hardly any politics in Bande à part. The story of the massacre of Tutsis by Hutus in Rwanda, even if it mentions Peking, is a transformation of international politics into the stuff of myth: ‘The Hutus are sawing the legs off the giant Tutsis, their former masters, to turn them into ordinary men... The seven foot high king is forced to flee... Peking supports the Kingdom of Giants...’.

Saint Maurice

The film refers to Joinville as the location of the house to be robbed, but the Villa Antony is in Saint Maurice, just before Joinville.

The film refers to Joinville as the location of the house to be robbed, but the Villa Antony is in Saint Maurice, just before Joinville.

Shakespeare

The film’s first set-piece is the language class, where the teacher reads from Romeo and Juliet in French for her students to translate back into Shakespeare’s English. The text she reads is a montage of fragments from the beginning, middle and end of the play, though not in that order. This composite nonsense becomes a tour de force of expressivity through the teacher, transforming what should be a mechanical reading into an intense and actorly performance, even making the phrases repeated for clarity into vehicles of feeling:

The film’s first set-piece is the language class, where the teacher reads from Romeo and Juliet in French for her students to translate back into Shakespeare’s English. The text she reads is a montage of fragments from the beginning, middle and end of the play, though not in that order. This composite nonsense becomes a tour de force of expressivity through the teacher, transforming what should be a mechanical reading into an intense and actorly performance, even making the phrases repeated for clarity into vehicles of feeling:

|

Act V scene 3:

Act II scene 2: Prologue: Act I scene 4: Act III scene 5: |

Go, get thee hence, for I will not away.

What's here? a cup, clos'd in my true love's hand? Poison, I see, hath been his timeless end:-- O churl! drink all, and left no friendly drop To help me after?--I will kiss thy lips; Haply some poison yet doth hang on them, To make me die with a restorative. […] Let me die. […] The ground is bloody; search about the churchyard: Go, some of you, whoe'er you find attach. Pitiful sight! here lies the county slain;-- And Juliet bleeding; warm, and newly dead, Who here hath lain this two days buried.-- Go, tell the prince. […] We see the ground whereon these woes do lie; But the true ground of all these piteous woes We cannot without circumstance descry. A thousand times the worse to want thy light. Love goes toward love as schoolboys from their books, But love from love, toward school with heavy looks. In fair Verona, where we lay our scene, […] A pair of star-cross'd lovers are born; […] The fearful passage of their death-mark'd love, […] Is now the two hours' traffic of our stage. True, I talk of dreams, Which are the children of an idle brain, Begot of nothing but vain fantasy, Which is as thin of substance as the air And more inconstant than the wind, who wooes Even now the frozen bosom of the north, And, being anger'd, puffs away from thence, Turning his face to the dew-dropping south. […] my mind misgives Some consequence, yet hanging in the stars, Shall bitterly begin his fearful date With this night's revels; and expire the term Of a despised life, clos'd in my breast, By some vile forfeit of untimely death. O fortune, fortune! all men call thee fickle. |

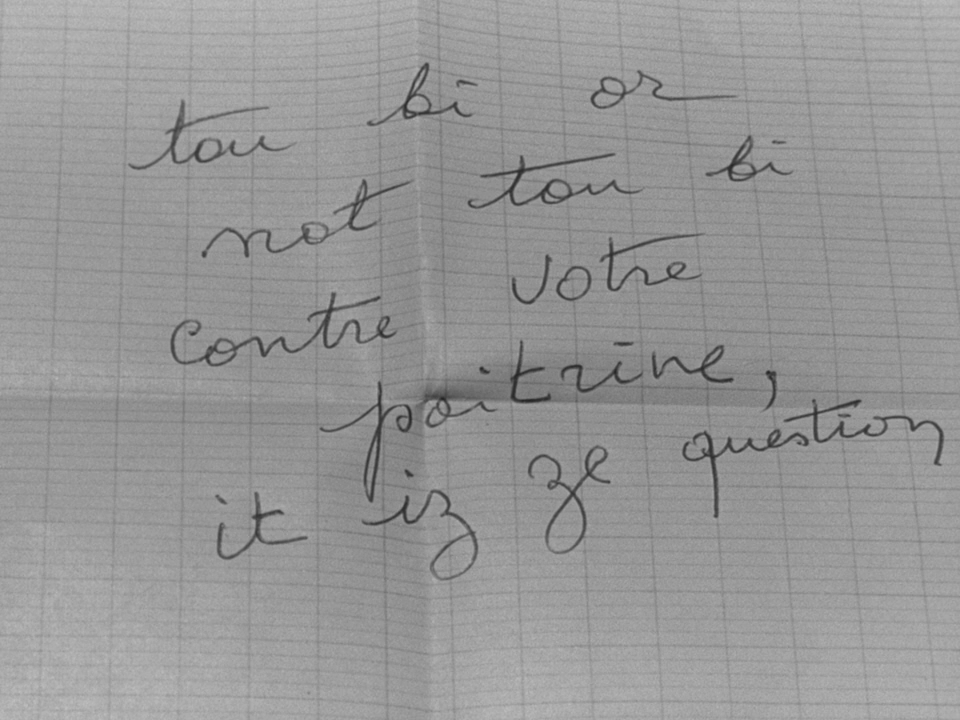

Her seriousness is set against Arthur’s bad Shakespearean joke ('Tou bi or not tou bi...'), in case we try to find in Bande à part a tragic story of ‘star-cross'd lovers’. Jean-Luc and Anna are not Romeo and Juliet.

There is a detailed discussion of the Shakespeare scene in Thomas Cartelli and Katherine Rowe's New Wave Shakespeare on Screen (2007), pp.46-8:

|

Simca

Franz dreams of owning a Ferrari to race at Indianapolis, but in the meantime Bande à part is a hymn to the car in which Franz and Arthur drive around (borrowed from Antoine Bourseiller, according to Baecque): a 1954 Simca Sport Weekend (thank you IMCDB). |

It is the first object the film fixes on, leaving Paris for the suburbs, and remains an object of constant attention. Filmed from every side, from above and below, and from inside, the car dictates framing and camera movement as if it were a character. Indeed, when Franz and Arthur toss a coin to decide who will sleep with Odile, the loser gets the car.

A similar Simca Sport Weekend featured at the end of A bout de souffle.

Tigers

|

Odile takes a steak from the fridge and brings it to Rajah, a tiger from a circus encamped nearby (the world-famous Cirque Fanní). Seeing the tiger half explains the roaring we heard a few minutes earlier, but why the tiger in the first place? Not all the oddities in Godard can, or should, be explained, but I think this is a visual gag, a pun on Chabrol’s upcoming film, Le Tigre aime la chair fraîche (‘The tiger likes fresh meat’). |

Chabrol, in that film, certainly called the midget assassin Jean-Luc as a homage to Godard. The midget actor Jimmy Karoubi would later reprise this role in Godard’s Pierrot le fou:

Truffaut

We remember Truffaut’s La Peau douce, made a few months before Bande à part, when Odile’s soft skin is commented on, or when the removal of her stockings is somewhat different from the stocking-removal scene in Truffaut’s film:

We remember Truffaut’s La Peau douce, made a few months before Bande à part, when Odile’s soft skin is commented on, or when the removal of her stockings is somewhat different from the stocking-removal scene in Truffaut’s film:

Godard remembers Truffaut when he calls the Place de Clichy one of the most beautiful in Paris. These reminiscences, alongside the ‘nouvelle vague’ neon shop sign and the echoes of Demy, Chabrol and Rohmer, are signs of separation, of Godard moving on.

Umbrellas

A few months before Bande à part, Michel Legrand wrote the score for Jacques Demy’s Les Parapluies de Cherbourg. We are reminded of this fact a few minutes into Godard’s film when Legrand’s lilting main theme is faded out in favour of Sami Frey’s whistling, a tuneless rendition of the main theme from Parapluies. When the Bande à part theme returns Frey whistles over it, both spoiling its effect and pointing out how similar the two are. Later, in the central café scene of Bande à part, Karina goes to the washroom by passing through the downstairs billiard room and we hear, piped from the jukebox upstairs to inadequate speakers, the distorted voice of Catherine Deneuve singing the same theme from Parapluies. This looks like rudeness, but twenty four years later, in his Histoire(s) du cinéma, Godard makes amends with a respectful and serious citation of Legrand’s theme.

Another connection with Les Parapluies de Cherbourg is the appearance in Bande à part of the same 1960 Mercedes-Benz 180 used at the end of Demy's film. Alain Bergala (Godard au travail, p.196) relates that the car belonged to Maurice Urbain, production manager on both films:

A few months before Bande à part, Michel Legrand wrote the score for Jacques Demy’s Les Parapluies de Cherbourg. We are reminded of this fact a few minutes into Godard’s film when Legrand’s lilting main theme is faded out in favour of Sami Frey’s whistling, a tuneless rendition of the main theme from Parapluies. When the Bande à part theme returns Frey whistles over it, both spoiling its effect and pointing out how similar the two are. Later, in the central café scene of Bande à part, Karina goes to the washroom by passing through the downstairs billiard room and we hear, piped from the jukebox upstairs to inadequate speakers, the distorted voice of Catherine Deneuve singing the same theme from Parapluies. This looks like rudeness, but twenty four years later, in his Histoire(s) du cinéma, Godard makes amends with a respectful and serious citation of Legrand’s theme.

Another connection with Les Parapluies de Cherbourg is the appearance in Bande à part of the same 1960 Mercedes-Benz 180 used at the end of Demy's film. Alain Bergala (Godard au travail, p.196) relates that the car belonged to Maurice Urbain, production manager on both films:

Une fille et des fusils

Claude Lelouch's bad New Wave film from 1965 features a band of outsiders preparing crime and pays explicit homage to Bande à part by showing an advertisement for Godard's film in France-Soir:

Claude Lelouch's bad New Wave film from 1965 features a band of outsiders preparing crime and pays explicit homage to Bande à part by showing an advertisement for Godard's film in France-Soir:

Verlaine

'C'est solitaire et glacé par ici', says Arthur Rimbaud, quoting Paul Verlaine's 'Colloque sentimental'.

'C'est solitaire et glacé par ici', says Arthur Rimbaud, quoting Paul Verlaine's 'Colloque sentimental'.

Le Week-End (2013)

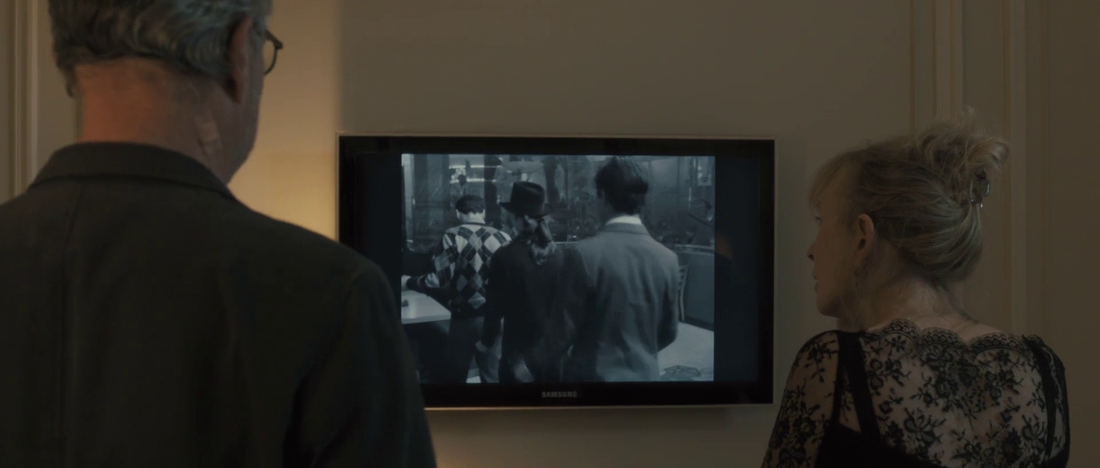

This awful English film shows two people watching and then dancing along to the sequence from Bande à part, which happens to be on the tv in their hotel room (at the Plaza Athénée on Avenue Montaigne). This homage is as bad as the Louvre scene in The Dreamers:

This awful English film shows two people watching and then dancing along to the sequence from Bande à part, which happens to be on the tv in their hotel room (at the Plaza Athénée on Avenue Montaigne). This homage is as bad as the Louvre scene in The Dreamers:

Wong Kar-Wai

The cliché is that Wong Kar-Wai is the new Godard (with competition in Hong Kong from Patrick Tam, Johnnie To and others). The influence of early Godard is there in his manner and method, and in his tragic male figures. The hero of Days of Being Wild sees himself exactly as Arthur sees himself: a bird with no legs, who must fly until the moment of his death.

The cliché is that Wong Kar-Wai is the new Godard (with competition in Hong Kong from Patrick Tam, Johnnie To and others). The influence of early Godard is there in his manner and method, and in his tragic male figures. The hero of Days of Being Wild sees himself exactly as Arthur sees himself: a bird with no legs, who must fly until the moment of his death.

Godard's 1964 press release for Bande à part

"Odile” Karina

Elle arrive en droite ligne du romantisme anglais du 19e siècle, mais elle arrive aussi, et en ligne beaucoup plus droite, du classicisme allemand du siècle d’avant. C’est dire que chez elle, se conjuguent plus que parfaitement, la spontanéité de la gentille Sarn au bec-de-lièvre, le goût de la nature de l’Odile des Affinités électives, et l’orgueil désenchanté de la malheureuse Tess. Errant entre le premier et le deuxième degré, entre Franz et Arthur, Odile, d’ailleurs, on le dit dans le film, commet sincèrement l’erreur de raisonner par rapport aux événements et non aux hommes. Elle se sent alors cernée au lieu de se sentir entourée et elle réagit donc aux sollicitations du monde d’une manière purement animale, sans raison logique apparente. Odile n’est jamais à la fois triste ou gaie, à la fois douce et violente, à la fois tendre et distante, ainsi que dans un film normal et psychologique du Bois Sacré d’Hollywood. Elle vit au contraire au jour le jour, c’est-à-dire au sentiment. Le sentiment qu’elle partage l’un après l’autre plutôt que tous ensemble, ce qui est le signe d’un cœur simple et poli. Pendant une minute, Odile c’est Leslie Caron dans Orvet, ou Lili et, brusquement, c’est Cathy O’Donell dans Les amants de la nuit. Pendant trois secondes, Odile court le long de la rivière comme Jennifer Jones pédalait dans Cluny Brown et, tout à coup, le destin la met au bord des larmes comme Sylvia Sydney dans l’immortel film de Lang.

... et Anna Karina

Il fallait une jeune et jolie fille comme Anna Karina pour jouer ce rôle qui existe toujours dans les faits divers et jamais dans les cours d’art dramatique. Élevée dans la grande et sévère tradition des Asta Nielsen, Garbo (celle de Stiller), Pola Negri, Anna (c’est ma femme et je l’aime, mais ça ne change rien à la vérité) sait introduire un peu d’air dans ce corset sublime et l’on respire alors un parfum très moderne, celui de l’improvisation chère à la comédie italienne, le néo-réalisme d’autrefois. En faisant voler son métier au secours de son talent, ce qui est très exactement l’inverse d’un jeu académique, Anna Karina arrive ainsi à faire pleurer Marianne avec les yeux de Bérénice en réconciliant Stanislawski et Diderot, Cukor et Bresson, Eisenstein et Rouch.

“Arthur” Brasseur

Né dans le limon, pas très loin de Rueil, tout comme les enfants du célèbre écrivain Queneau, Arthur est un de ces personnages pour qui les métaphores n’ont jamais besoin d’explications. Il croit en effet aux décors et aux apparences, à Billy le Kid comme à Cyd Charisse. Autrement dit, c’est un garçon pour qui la vie est totalement dénuée de mystères, mais avec toute la poésie qu’implique le mot total. Autrement dit, encore et plus exactement un garçon pour qui le mystère de la vie n’est pas forcément caché dans une lointaine forêt de Brocéliande, mais peut-être bien sur l’autoroute de l’Est où l’on va et vient en poussant au fond sa Simca plein ciel. Peut-être bien aussi derrière un comptoir de café de la Porte de Vincennes quand on danse en ligne un Madison imaginaire pour retrouver les temps perdus par Anabella et Préjean, un 14 juillet, sous les toits de Paris. On l’a compris, Arthur est un personnage du premier degré, un personnage de roman de gare. Il a pris le parti de choses et les choses ont pris le sien. Une juste mort viendra donc sanctionner celui qui n’avait pas peur de la vie.

... et Claude Brasseur

Pour jouer ce rôle, Claude Brasseur était l’idéal car il a l’innocence et la folie des enfants lorsqu’ils jouent aux billes ou à la guerre, c’est-à-dire à la fois la brutalité nécessaire et la candeur suffisante, et vice versa. Bref, il fait partie de cette catégorie assez rare d’acteurs qui ne peuvent s’empêcher de jouer la comédie, ou la tragédie, comme des hommes, les hommes qu’ils sont, faiblesse qui fait leur grandeur.

“Franz” Frey

Si l’on met les problèmes de Franz en équation, elle sera presque à coup sûr du second degré, comme celle de ses grands aînés, le Cid, Lorenzaccio. Car Franz prend tout à l’envers, la vie, la mort et son amour pour Odile qui finira donc par là où il n’avait pas commencé, le calme et le bonheur. A l’image des enfants humiliés de Bernanos, Franz s’installe volontiers et tout de suite dans le drame, l’amertume, le malheur, comme dans le collège de son enfance. A la moindre occasion, on le verra ainsi entamer un long voyage jusqu’au bout de sa propre nuit, à la recherche d’une Eurydice qui n’est jamais autre que lui-même. Il saute à travers tous les miroirs chers à Cocteau, comme un suicidé par la fenêtre, et s’il s’en tire sain d’esprit, et sauf de corps par on ne sait quel miracle, c’est que Franz cache sans doute un cœur de Richard III sous un imperméable acheté dans un roman de Simenon. Sans doute, est-il lui aussi toujours prêt, comme les petits loups, à donner son royaume de banlieue contre une vingt-quatre cylindrée en V pour gagner la bataille d’Indianapolis. La force et l’originalité de Franz, dans notre époque pourrie par les IBM des fonctionnaires, sont d’avoir gardé intactes ces réserves d’imaginaire vantées par les surréalistes... Il a rencontré Odile près de la Bastille comme naguère Breton avait croisé Nadja, au carrefour de l’insolite et du réel. Tels sont les héros décrits par Novalis, Franz prendra donc toujours la réalité pour ses désirs, car il sent bien que si le monde devient rêve, à son tour, une belle fois pour toutes, le rêve deviendra monde.

... et Sami Frey

Il fallait évidemment Sami Frey pour interpréter un semblable personnage. Sami que je vois souvent rôder le soir à l’heure où s’allument les lumières dans la Jungle des villes, méfiant et tragique au volant de sa grosse et longue Jaguar. Sami, qui sait jouer Brecht et Claudel comme les Français ne le savent pas, avec cette sorte de passion dont Bossuet entretenait Henriette d’Angleterre, cette rage qu’enfièvre la logique. Sami, avec qui je tournerai un jour William Wilson de Poe, lequel n’a de cesse qu’il ne soit arrivé à tuer quelqu’un parce qu’il lui ressemblait trop, et s’aperçoit alors qu’il s’est tué lui-même, et que c’est son double qui reste vivant. Sami qui, s’il ne l’était pas déjà, deviendra un grand acteur.

Odile, Arthur et Franz, les personnages de Bande à part

Ils se lèvent le matin, il faut trouver un oiseau à manger à midi, un autre pour manger le soir. Entre-temps, ils vont boire à la rivière, et puis voilà. Ils vivent selon l’instinct, selon l’instant. Ils n'ont pas une mentalité de voleurs, ni de capitalistes. Ils sont comme des animaux. Pour le moment, ils sont heureux parce qu'ils ne se posent pas de questions. Ce sont des gens réels, et c'est le monde qui fait bande à part, c'est le monde qui se fait du cinéma, qui n'est pas synchrone. Eux sont justes, sont vrais, ils représentent la vie. Ils vivent une histoire simple, c'est le monde autour d'eux qui vit un mauvais scénario.

Elle arrive en droite ligne du romantisme anglais du 19e siècle, mais elle arrive aussi, et en ligne beaucoup plus droite, du classicisme allemand du siècle d’avant. C’est dire que chez elle, se conjuguent plus que parfaitement, la spontanéité de la gentille Sarn au bec-de-lièvre, le goût de la nature de l’Odile des Affinités électives, et l’orgueil désenchanté de la malheureuse Tess. Errant entre le premier et le deuxième degré, entre Franz et Arthur, Odile, d’ailleurs, on le dit dans le film, commet sincèrement l’erreur de raisonner par rapport aux événements et non aux hommes. Elle se sent alors cernée au lieu de se sentir entourée et elle réagit donc aux sollicitations du monde d’une manière purement animale, sans raison logique apparente. Odile n’est jamais à la fois triste ou gaie, à la fois douce et violente, à la fois tendre et distante, ainsi que dans un film normal et psychologique du Bois Sacré d’Hollywood. Elle vit au contraire au jour le jour, c’est-à-dire au sentiment. Le sentiment qu’elle partage l’un après l’autre plutôt que tous ensemble, ce qui est le signe d’un cœur simple et poli. Pendant une minute, Odile c’est Leslie Caron dans Orvet, ou Lili et, brusquement, c’est Cathy O’Donell dans Les amants de la nuit. Pendant trois secondes, Odile court le long de la rivière comme Jennifer Jones pédalait dans Cluny Brown et, tout à coup, le destin la met au bord des larmes comme Sylvia Sydney dans l’immortel film de Lang.

... et Anna Karina

Il fallait une jeune et jolie fille comme Anna Karina pour jouer ce rôle qui existe toujours dans les faits divers et jamais dans les cours d’art dramatique. Élevée dans la grande et sévère tradition des Asta Nielsen, Garbo (celle de Stiller), Pola Negri, Anna (c’est ma femme et je l’aime, mais ça ne change rien à la vérité) sait introduire un peu d’air dans ce corset sublime et l’on respire alors un parfum très moderne, celui de l’improvisation chère à la comédie italienne, le néo-réalisme d’autrefois. En faisant voler son métier au secours de son talent, ce qui est très exactement l’inverse d’un jeu académique, Anna Karina arrive ainsi à faire pleurer Marianne avec les yeux de Bérénice en réconciliant Stanislawski et Diderot, Cukor et Bresson, Eisenstein et Rouch.

“Arthur” Brasseur

Né dans le limon, pas très loin de Rueil, tout comme les enfants du célèbre écrivain Queneau, Arthur est un de ces personnages pour qui les métaphores n’ont jamais besoin d’explications. Il croit en effet aux décors et aux apparences, à Billy le Kid comme à Cyd Charisse. Autrement dit, c’est un garçon pour qui la vie est totalement dénuée de mystères, mais avec toute la poésie qu’implique le mot total. Autrement dit, encore et plus exactement un garçon pour qui le mystère de la vie n’est pas forcément caché dans une lointaine forêt de Brocéliande, mais peut-être bien sur l’autoroute de l’Est où l’on va et vient en poussant au fond sa Simca plein ciel. Peut-être bien aussi derrière un comptoir de café de la Porte de Vincennes quand on danse en ligne un Madison imaginaire pour retrouver les temps perdus par Anabella et Préjean, un 14 juillet, sous les toits de Paris. On l’a compris, Arthur est un personnage du premier degré, un personnage de roman de gare. Il a pris le parti de choses et les choses ont pris le sien. Une juste mort viendra donc sanctionner celui qui n’avait pas peur de la vie.

... et Claude Brasseur

Pour jouer ce rôle, Claude Brasseur était l’idéal car il a l’innocence et la folie des enfants lorsqu’ils jouent aux billes ou à la guerre, c’est-à-dire à la fois la brutalité nécessaire et la candeur suffisante, et vice versa. Bref, il fait partie de cette catégorie assez rare d’acteurs qui ne peuvent s’empêcher de jouer la comédie, ou la tragédie, comme des hommes, les hommes qu’ils sont, faiblesse qui fait leur grandeur.

“Franz” Frey

Si l’on met les problèmes de Franz en équation, elle sera presque à coup sûr du second degré, comme celle de ses grands aînés, le Cid, Lorenzaccio. Car Franz prend tout à l’envers, la vie, la mort et son amour pour Odile qui finira donc par là où il n’avait pas commencé, le calme et le bonheur. A l’image des enfants humiliés de Bernanos, Franz s’installe volontiers et tout de suite dans le drame, l’amertume, le malheur, comme dans le collège de son enfance. A la moindre occasion, on le verra ainsi entamer un long voyage jusqu’au bout de sa propre nuit, à la recherche d’une Eurydice qui n’est jamais autre que lui-même. Il saute à travers tous les miroirs chers à Cocteau, comme un suicidé par la fenêtre, et s’il s’en tire sain d’esprit, et sauf de corps par on ne sait quel miracle, c’est que Franz cache sans doute un cœur de Richard III sous un imperméable acheté dans un roman de Simenon. Sans doute, est-il lui aussi toujours prêt, comme les petits loups, à donner son royaume de banlieue contre une vingt-quatre cylindrée en V pour gagner la bataille d’Indianapolis. La force et l’originalité de Franz, dans notre époque pourrie par les IBM des fonctionnaires, sont d’avoir gardé intactes ces réserves d’imaginaire vantées par les surréalistes... Il a rencontré Odile près de la Bastille comme naguère Breton avait croisé Nadja, au carrefour de l’insolite et du réel. Tels sont les héros décrits par Novalis, Franz prendra donc toujours la réalité pour ses désirs, car il sent bien que si le monde devient rêve, à son tour, une belle fois pour toutes, le rêve deviendra monde.

... et Sami Frey

Il fallait évidemment Sami Frey pour interpréter un semblable personnage. Sami que je vois souvent rôder le soir à l’heure où s’allument les lumières dans la Jungle des villes, méfiant et tragique au volant de sa grosse et longue Jaguar. Sami, qui sait jouer Brecht et Claudel comme les Français ne le savent pas, avec cette sorte de passion dont Bossuet entretenait Henriette d’Angleterre, cette rage qu’enfièvre la logique. Sami, avec qui je tournerai un jour William Wilson de Poe, lequel n’a de cesse qu’il ne soit arrivé à tuer quelqu’un parce qu’il lui ressemblait trop, et s’aperçoit alors qu’il s’est tué lui-même, et que c’est son double qui reste vivant. Sami qui, s’il ne l’était pas déjà, deviendra un grand acteur.

Odile, Arthur et Franz, les personnages de Bande à part

Ils se lèvent le matin, il faut trouver un oiseau à manger à midi, un autre pour manger le soir. Entre-temps, ils vont boire à la rivière, et puis voilà. Ils vivent selon l’instinct, selon l’instant. Ils n'ont pas une mentalité de voleurs, ni de capitalistes. Ils sont comme des animaux. Pour le moment, ils sont heureux parce qu'ils ne se posent pas de questions. Ce sont des gens réels, et c'est le monde qui fait bande à part, c'est le monde qui se fait du cinéma, qui n'est pas synchrone. Eux sont justes, sont vrais, ils représentent la vie. Ils vivent une histoire simple, c'est le monde autour d'eux qui vit un mauvais scénario.