the place of cinema: cinema as location in Vivre sa vie

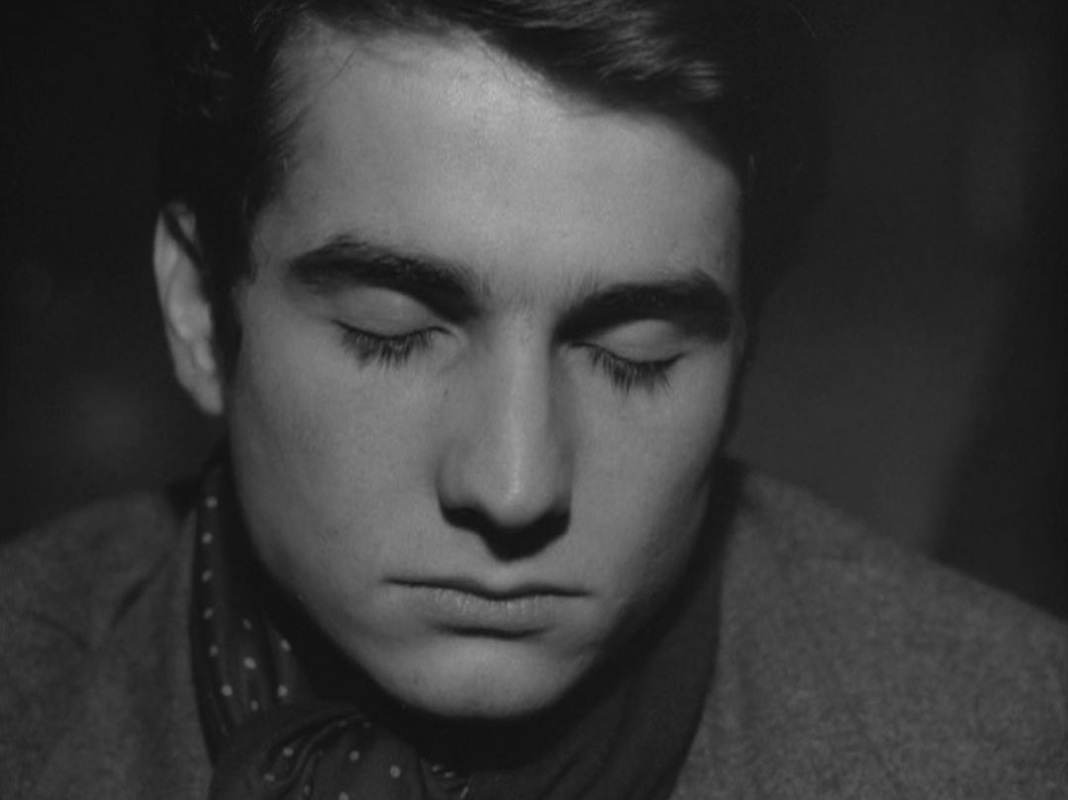

Famously, Nana goes to the cinema. The film she sees is Dreyer's La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc (1928), a silent film which she watches in silence, or almost: about half way through the two-minute sequence shown, the man she is with says out loud the name of the actress on the screen, 'Falconetti'.

There is a matching of attitude and - to a lesser extent - shot scale between the film being watched and the film of the person watching. The neatness of the match is one reason why this is a famous 'film-within-a-film' sequence, generating readings that see Godard's close-ups as Dreyeresque and Nana's death as Jeannesque. Nana can even seem Falconetti-esque, given the story that Dreyer's actress went from film star to prostitute, and that would-be film star Nana also becomes a prostitute.

Different readings would be in circulation if Godard had stuck to earlier plans. A preliminary outline of Vivre sa vie describes Nana (Anna Karina) going to see Otto Preminger's River of No Return (1954). This would have chimed with a scene at the cinema from A bout de souffle (1960), when Patricia (Jean Seberg) goes into the MacMahon as Preminger's Whirlpool (1949) is showing, but would have otherwise created some striking disharmonies. Of format firstly, since River of No Return is in Technicolor and Cinemascope (2.55:1). To insert it into the 1.37:1 frame of the black-and-white Vivre sa vie might have required presenting a debased image of Preminger's film:

Different readings would be in circulation if Godard had stuck to earlier plans. A preliminary outline of Vivre sa vie describes Nana (Anna Karina) going to see Otto Preminger's River of No Return (1954). This would have chimed with a scene at the cinema from A bout de souffle (1960), when Patricia (Jean Seberg) goes into the MacMahon as Preminger's Whirlpool (1949) is showing, but would have otherwise created some striking disharmonies. Of format firstly, since River of No Return is in Technicolor and Cinemascope (2.55:1). To insert it into the 1.37:1 frame of the black-and-white Vivre sa vie might have required presenting a debased image of Preminger's film:

The alternative, switching to widescreen colour for the shots of the screen, would have been unfeasibly expensive and aesthetically crass. (That said, Varda's Cléo de 5 à 7 and Reichenbach's Un coeur gros comme ça, both from the same year as Vivre sa vie, were black-and-white with a brief passage of colour.)

Even if Nana were shown watching River of No Return in black and white, there are no Dreyer-like extreme close-ups in Preminger's film (as befits its aspect ratio), so that the match with that aspect of Godard's style in Vivre sa vie would be lost. And there are no scenes where Marilyn cries, so Nana's Bovaryesque identification with the heroine's suffering would also have to be sacrificed.

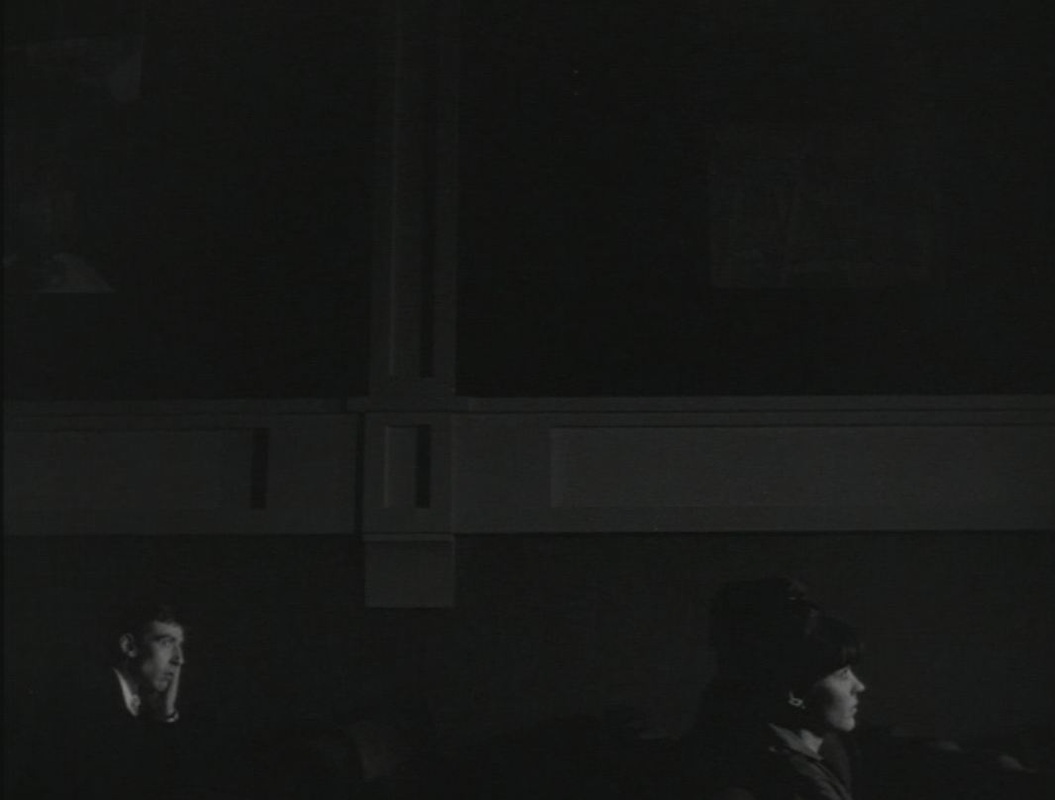

Marilyn Monroe is evoked as object of the gaze in a later film-going scene, when the characters of Masculin-Féminin (1966) are in a cinema in Montparnasse. On the screen is Bergmanesque erotica, but the voice-over, borrowing from Perec's novel Les Choses (1965), is thinking of another film (The Misfits, perhaps):

‘We often went to the cinema. The screen lit up and we'd shiver. But usually Madeleine and I were disappointed. The images flickered. Marilyn Monroe looked terribly old. We were sad. It wasn't the film we had dreamed of, that complete film we each carried within us, the film we would have wanted to make, or, more secretly, would have wanted to live.’

‘We often went to the cinema. The screen lit up and we'd shiver. But usually Madeleine and I were disappointed. The images flickered. Marilyn Monroe looked terribly old. We were sad. It wasn't the film we had dreamed of, that complete film we each carried within us, the film we would have wanted to make, or, more secretly, would have wanted to live.’

Another option considered by Godard for the film within Vivre sa vie was Bresson's Le Procès de Jeanne d'Arc (1962). Permissions had been obtained and material supplied, and it isn't entirely clear why the plan was abandoned in favour of the earlier Jeanne d'Arc film. Perhaps the reference to Dreyer was once again a homage to Anna Karina's Danish origins, after she had played 'Veronika Dreyer' in Le Petit Soldat (1960). Or it may be that a shared interest in the extreme close-up was determining, since Bresson's film, like Preminger's, has none. The closest are these:

Inserting Le Procès de Jeanne d'Arc would again have entailed a mismatch of aspects (1.37:1 and 1.66:1), though that would have been less disruptive than with River of No Return. The adjustments might not have been noticed:

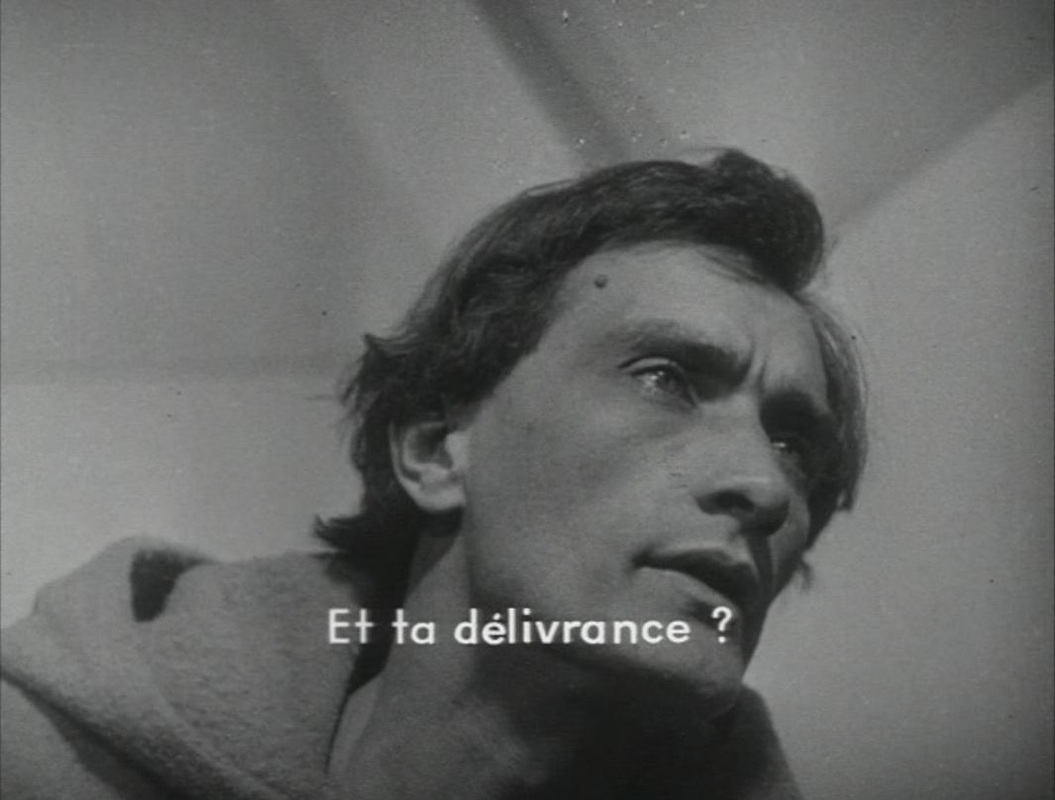

Since the difference between its 1.33:1 and the 1.37:1 of Vivre sa vie is slight, the use of Dreyer's film avoids such formal complications, but it does raise others. The version of the Passion that Nana could feasibly have seen in a Paris cinema c. 1962 was the one prepared in 1952 by the Cahiers du cinéma's Lo Duca. This 'notorious' and 'objectionable' version (see Bordwell, p.xi) played regularly in arthouses throughout the following decades, until superseded by more authentic restorations in the 1980s. The extract used in Vivre sa vie draws particular attention to Lo Duca's practice of occasionally suppressing intertitles and replacing them with subtitles:

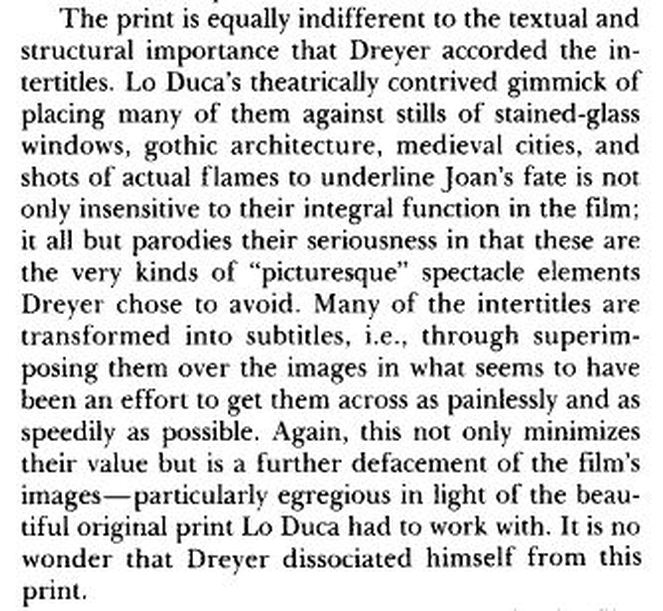

Lo Duca's version has also been heavily criticised for its reworking of the intertitles. Here is Tony Pipolo (p.310) on the subject:

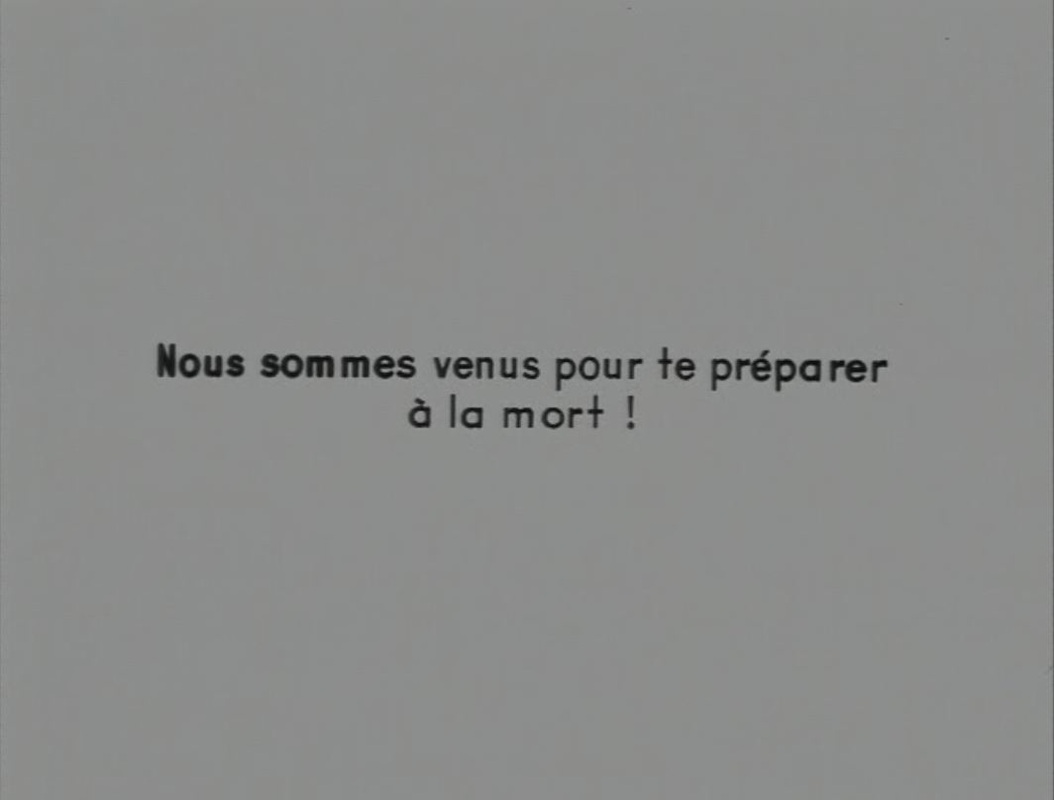

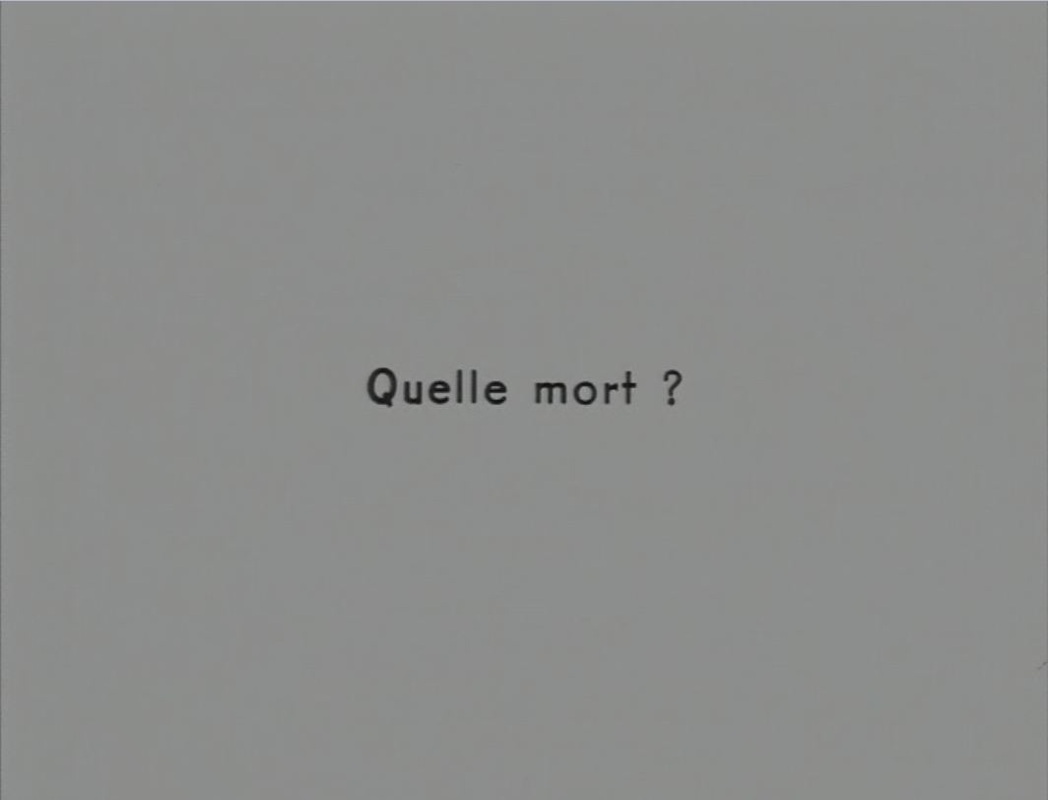

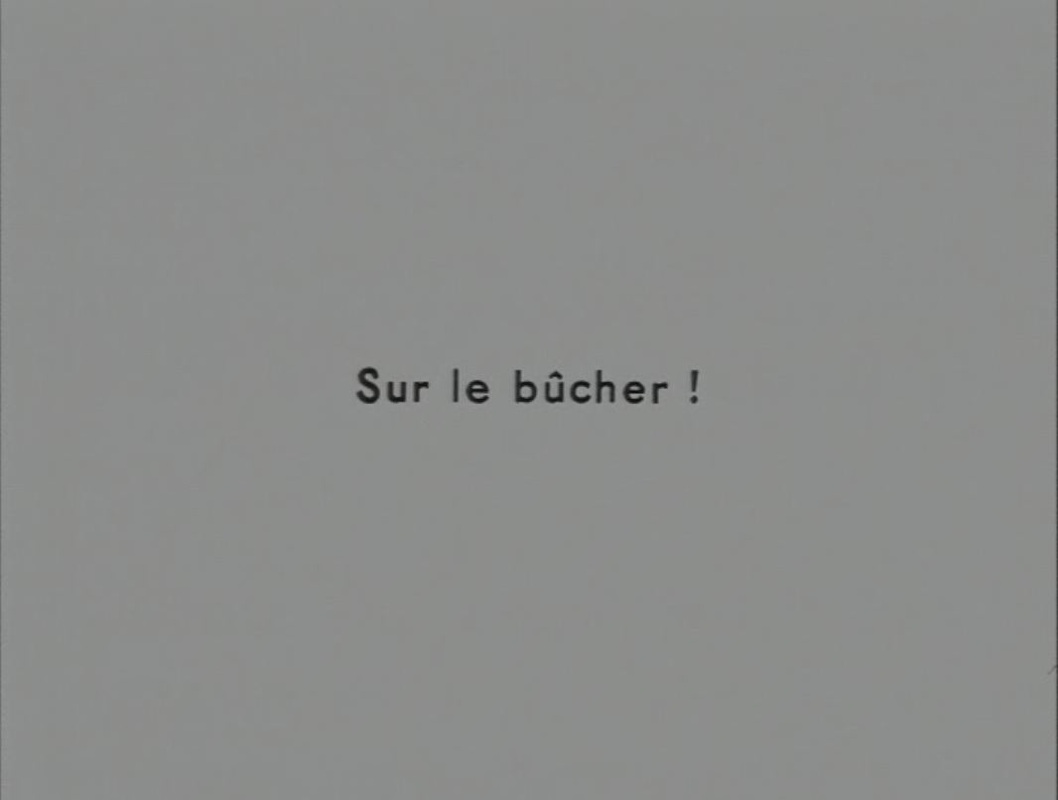

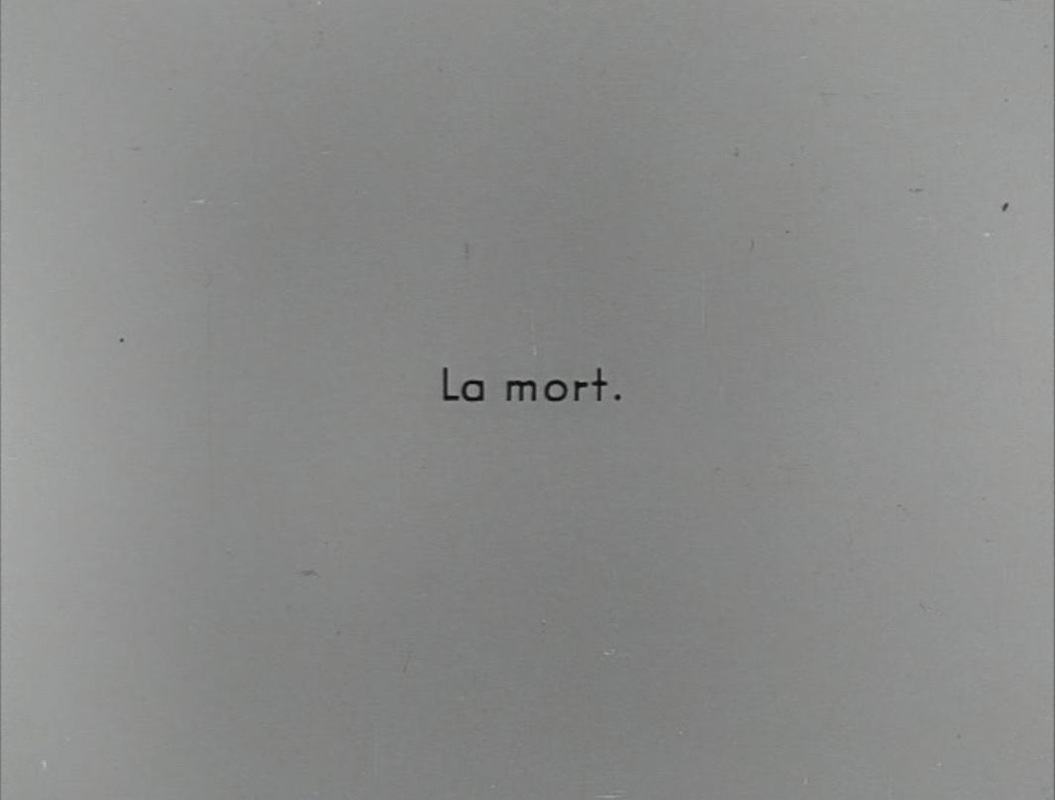

There are four subtitles and eight intertitles in the extract Godard uses, and none of the intertitles is of the kind Pipolo describes above. My memory of the occasions on which I saw the Lo Duca version (more than twenty-five years ago) isn't up to determining whether the more neutral intertitles in the passage Godard shows were Lo Duca's, exercising rare restraint, or whether they were placed there by Godard. The typeface suggests to me a Godardian minimalism, but I would have to find a copy of the now rare Lo Duca edition to know for sure:

Two more aspects of Lo Duca's version leave their mark on the scene in Vivre sa vie. Lo Duca had added sound to Dreyer's film, both narration and music. Pipolo explains very clearly what a travesty this was, and we may conclude that Godard thought the same, since he has Nana watch the film in silence, suppressing the Bach, Vivaldi and 'Albinoni' that Lo Duca had seen fit to add.

Furthermore, adding a soundtrack entailed 'cropping the left side of the image' (Pipolo, p.307), radically altering Dreyer's compositions. We can see here the difference between the same moment in the Lo Duca version (as seen in Vivre sa vie) and in the 1985 restoration by the Cinémathèque française, from a print found in 1981:

Furthermore, adding a soundtrack entailed 'cropping the left side of the image' (Pipolo, p.307), radically altering Dreyer's compositions. We can see here the difference between the same moment in the Lo Duca version (as seen in Vivre sa vie) and in the 1985 restoration by the Cinémathèque française, from a print found in 1981:

The point to notice here is the decentred framing in the more authentic version (on the left), altered by the cropping of the left side in the mutilated version (right).

But you will also notice that the image itself is not exactly the same. This reflects the long and complicated history of multiple versions of the film, including recuts using alternative takes after a first cut was destroyed. Every shot in the Lo Duca version used by Godard is a different take from the corresponding shots in the restored version.

The changes are not all as striking as above: in one instance, a tear is rolling in one version and not in the other.

I must refer you to Tony Pipolo's essay for clarification of these questions, because this is not my area of expertise, and I have just remembered that this piece is supposed to be about the cinema as location.

In the preceding sequence, Nana is invited to dinner by her estranged husband, but she decides to head down the street to Saint Michel: 'I want to go to the cinema'. In the sequence that comes after, she leaves the man she was with at the cinema outside a café on the place de la Sorbonne (L'Escholier). We can safely assume that the cinema is somewhere in this general area, in the 5th arrondissement.

But you will also notice that the image itself is not exactly the same. This reflects the long and complicated history of multiple versions of the film, including recuts using alternative takes after a first cut was destroyed. Every shot in the Lo Duca version used by Godard is a different take from the corresponding shots in the restored version.

The changes are not all as striking as above: in one instance, a tear is rolling in one version and not in the other.

I must refer you to Tony Pipolo's essay for clarification of these questions, because this is not my area of expertise, and I have just remembered that this piece is supposed to be about the cinema as location.

In the preceding sequence, Nana is invited to dinner by her estranged husband, but she decides to head down the street to Saint Michel: 'I want to go to the cinema'. In the sequence that comes after, she leaves the man she was with at the cinema outside a café on the place de la Sorbonne (L'Escholier). We can safely assume that the cinema is somewhere in this general area, in the 5th arrondissement.

From the interior décor, we can recognise the cinema in which she watches La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc as the Panthéon, at 13 rue Victor Cousin, 5e. (We can also see the character Raoul, the pimp, sitting behind her in the cinema, just as he is behind Nana and her husband in the street above.)

I don't have a good picture of the Panthéon's auditorium, so you'll have to rely on my memory that this is what it looked like before recent refurbishments, and also on this photograph, from Salles-Cinema.com:

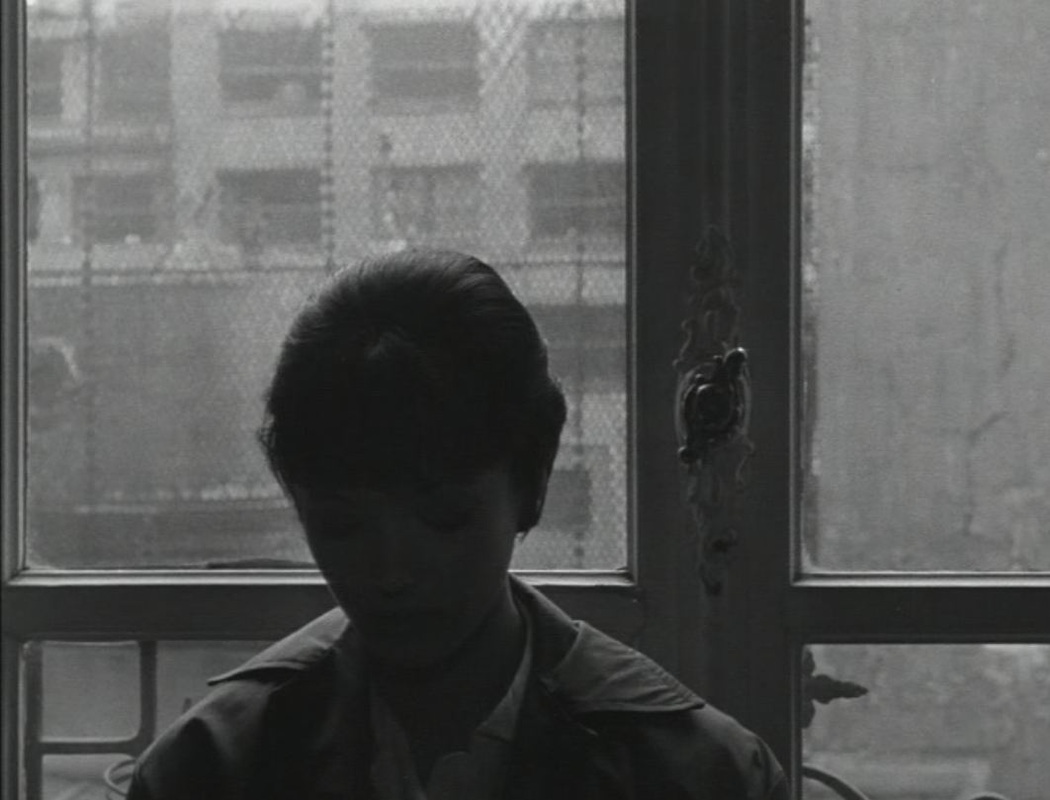

This is apparently Paris's oldest surviving cinema, dating from 1907 (see here). Since 1930 it had been owned by Pierre Braunberger, the producer of Vivre sa vie, so it is unsurprising that his cinema is used for the film. In similar fashion his production office was used to represent the police station to which Nana is brought a short while later:

(On the wall behind the policeman we can recognise the timidity-training photographs seen in Tirez sur le pianiste, a Braunberger production from two years before.)

The interior décor of the Panthéon is distinctive, but the exterior façade is even more so:

The interior décor of the Panthéon is distinctive, but the exterior façade is even more so:

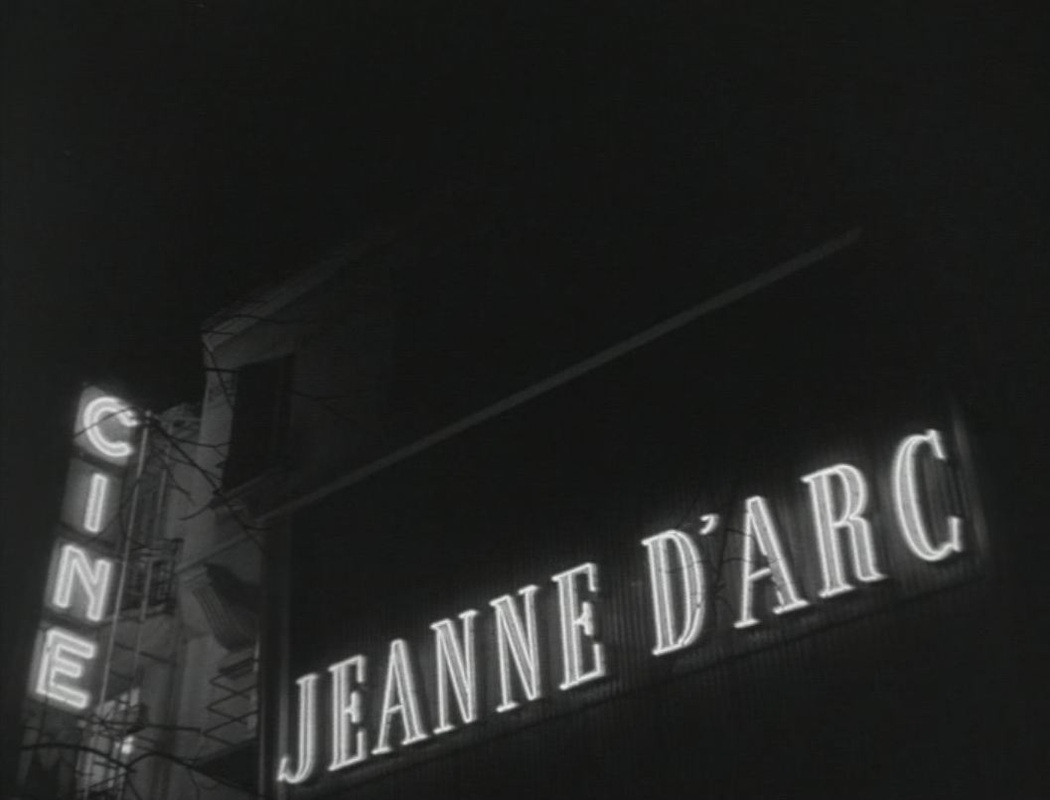

Here we face a problem. In Vivre sa vie, before we go inside the cinema we see its façade:

Even allowing that the sign over the entrance might change, the details we can see of each building don't match. There is nothing on the deco-ish façade of the Panthéon that is like the ornamental support just left of the name-board in the image above (which I have lightened slightly). And the Panthéon's vertical sign reading 'CINEMA' is in the wrong place and in the wrong typeface.

It looks like the cinema in Vivre sa vie combines two different locations. I've looked at the façades of every surviving cinema in the 5th and surrounding arrondissements, and many photographs of cinemas now gone, but none seems to match the cinema here.

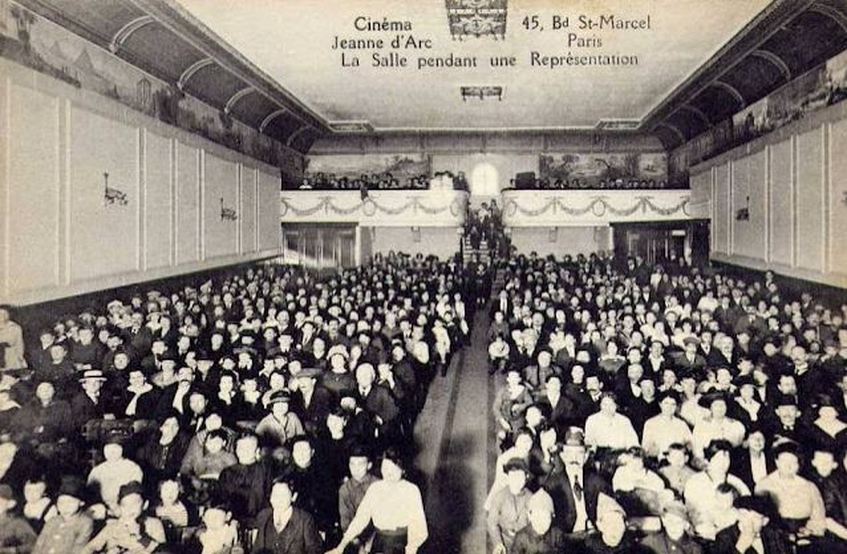

Comparing these two façades does still give us a clue to work with. The sign above the door of the Panthéon tells us the name of the cinema. Where is the name of the cinema in Vivre sa vie? The answer is: on the sign above the door. No film would have been advertised with a permanent illuminated sign of this kind, so 'Jeanne d'Arc' must be the name of the cinema. At 45 boulevard Saint Marcel, in the 13th arrondissement, stood the Jeanne d'Arc, a 'cinéma de quartier'. In its place now stands an apartment building:

It looks like the cinema in Vivre sa vie combines two different locations. I've looked at the façades of every surviving cinema in the 5th and surrounding arrondissements, and many photographs of cinemas now gone, but none seems to match the cinema here.

Comparing these two façades does still give us a clue to work with. The sign above the door of the Panthéon tells us the name of the cinema. Where is the name of the cinema in Vivre sa vie? The answer is: on the sign above the door. No film would have been advertised with a permanent illuminated sign of this kind, so 'Jeanne d'Arc' must be the name of the cinema. At 45 boulevard Saint Marcel, in the 13th arrondissement, stood the Jeanne d'Arc, a 'cinéma de quartier'. In its place now stands an apartment building:

Nothing in this picture provides corroboration for my conjecture, and I have looked for a long time for a photograph of the cinema that was there before - it was demolished in the 1970s. By chance last week I came across this photograph of that cinema in a collection of old postcards. It seems to be conclusive:

The photograph dates from the year after Vivre sa vie - the film playing is Jean Delannoy's Vénus impériale (1963). Here, thanks to Ciné-Façades, is an earlier view of the exterior and aview of the interior:

For the history of this cinema, which first opened in 1913, see Ciné-Façades, here.

In conclusion, then: having decided to have Nana watch a film about Joan of Arc (either Bresson's or Dreyer's), and for convenience deciding to film the interior scenes in a cinema owned by the film's producer, Godard also decided to make a little joke about the place of cinema and cinemas, placing one cinema, the Panthéon, within another, the Jeanne d'Arc, just as he was placing one film within another film.

Everyone involved in Vivre sa vie must have appreciated the joke. It has just taken the rest of us a little while to catch up.

In conclusion, then: having decided to have Nana watch a film about Joan of Arc (either Bresson's or Dreyer's), and for convenience deciding to film the interior scenes in a cinema owned by the film's producer, Godard also decided to make a little joke about the place of cinema and cinemas, placing one cinema, the Panthéon, within another, the Jeanne d'Arc, just as he was placing one film within another film.

Everyone involved in Vivre sa vie must have appreciated the joke. It has just taken the rest of us a little while to catch up.

References

David Bordwell, The Films of Carl-Theodor Dreyer (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979)

Tony Pipolo, 'The Spectre of Joan of Arc: Textual Variations in the Key Prints of Carl Dreyer's Film', Film History 2.4 (December 1988)

See here Constanze Ruhm revisiting locations in Vivre sa vie

David Bordwell, The Films of Carl-Theodor Dreyer (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979)

Tony Pipolo, 'The Spectre of Joan of Arc: Textual Variations in the Key Prints of Carl Dreyer's Film', Film History 2.4 (December 1988)

See here Constanze Ruhm revisiting locations in Vivre sa vie