The Paris of '50s Noir: Becker, Dassin and Melville

|

This post is based on the English draft of a piece that appeared in Slovakian last year, in a volume on the poetics of crime in French film noir, edited by Michal Michalovic and Martin Kanuch - see here. I am grateful to the editors for permission to use this material here. Also, my apologies if a little of the material seems familiar, having been recycled from earlier Cine-Tourist posts. |

Two petty criminals meet up outside La Coupole on the boulevard du Montparnasse. One of them is on the run from the police, and asks the other where he and his girlfriend might be able to spend the night. The girlfriend suggests that they could stay with a friend of hers in Montmartre, and gets a sharp answer: ‘No, not Montmartre… We’ve got too many enemies in Montmartre’:

Ten minutes or so from the end of A bout de souffle, this exchange presents Paris as a territorialised space, with demarcated zones of activity for different sets of criminals. Poiccard thinks he is safe in Montparnasse, at least from any Montmartre-based rivals (he will eventually be gunned down by the police in a Montparnasse street, a few metres from the cemetery).

This spatial opposition is also a temporal one, a distinction between this new (New Wave) crime film dated 1960 and the old school of 1950s French crime films, for which the criminal heartland of Paris was Montmartre. In the scene mentioned, A bout de souffle plays with this sense of its newness when, just before the discussion about Montmartre, Poiccard introduces his girlfriend to an associate, Carl Zombach, played by Roger Hanin. Zombach criticises Poiccard for wearing silk with tweed, borrowing dialogue from Dashiell Hammett’s 1931 novel The Glass Key:

This spatial opposition is also a temporal one, a distinction between this new (New Wave) crime film dated 1960 and the old school of 1950s French crime films, for which the criminal heartland of Paris was Montmartre. In the scene mentioned, A bout de souffle plays with this sense of its newness when, just before the discussion about Montmartre, Poiccard introduces his girlfriend to an associate, Carl Zombach, played by Roger Hanin. Zombach criticises Poiccard for wearing silk with tweed, borrowing dialogue from Dashiell Hammett’s 1931 novel The Glass Key:

As an actor, Hanin was firmly associated with the established mainstream of French crime thrillers: a year or so before A bout de souffle he had played the owner of a Montmartre nightclub in two different films, Gilles Grangier’s Le Désordre et la Nuit and Michel Deville’s Une Balle dans le canon:

His presence in Godard’s film is not, like the appearance earlier of director Jean-Pierre Melville, a homage to his type of filmmaking, but is part of the complex intertextuality that constitutes A bout de souffle: Hanin is, like the phrase from Hammett and like the reference to Montmartre, a quotation.

The Montmartre that Poiccard avoids needs defining. Internationally, Montmartre means the top of the butte, with the Sacré Coeur dominating the place du Tertre and its tourist-centred collection of restaurants and souvenir shops. Locally, Montmartre is the area to each side of the boulevard de Clichy and the boulevard Pigalle, comprising the streets on the lower slopes of the butte, in the eighteenth arrondissement, and those to the south, in the ninth arrondissement. (See Ginette Vincendeau on the relation of Montmartre to Pigalle in her book Jean-Pierre Melville: an American in Paris, p.107.) This, according to the clichés, is an underworld Montmartre of sex-trade and criminality, with at its hub the neon-bathed place Pigalle. Here, Montmartre and Pigalle are interchangeable terms. This was not a secret world: Pigalle had an international reputation, attracting tourists to its cabarets and stripclubs, as well as filmmakers wanting to give an authentic air to their fictional gangsters.

The New Wave, famously, marked a new direction in French cinema, and it is striking that Godard in A bout de souffle and Truffaut with Tirez sur le pianiste both sought to signal their newness with gangster-related crime films. Truffaut’s hostility to the gangster films of the French tradition was all the more strong in that their territory of predilection was his own: ‘I don’t like gangsters. I was born in Pigalle and, although I didn’t suffer from them directly, I saw what they were close up, bad guys who beat up women in the street…’ (François Truffaut, Interviews, p.118). Accordingly, Truffaut take his gangsters out of their traditional habitat, and though they are still violent men they are made to look like buffoons.

Despite the New Wave, the traditional French crime film continued to be successful, with old school directors and actors working on into the seventies (see René Clément, Jean Gabin), and new directors emerging who were happy to persist with the old formats (Edouard Molinaro, Jacques Deray, Georges Lautner). The gangster film in France has survived to this day, but with little or no New Wave input. We can, on the other hand, consider that the French gangster film had an impact on the New Wave, and hence on the history of cinema internationally.

Despite the New Wave, the traditional French crime film continued to be successful, with old school directors and actors working on into the seventies (see René Clément, Jean Gabin), and new directors emerging who were happy to persist with the old formats (Edouard Molinaro, Jacques Deray, Georges Lautner). The gangster film in France has survived to this day, but with little or no New Wave input. We can, on the other hand, consider that the French gangster film had an impact on the New Wave, and hence on the history of cinema internationally.

This essay considers what we see of Paris in French crime films of the 1950s, but ignores the vast majority of that output in order to concentrate on a nexus of three acknowledged classics made in 1954, 1955 and 1956: respectively, Jacques Becker’s Touchez pas au grisbi, Jules Dassin’s Du rififi chez les hommes and Jean-Pierre Melville’s Bob le flambeur. Touchez pas au grisbi shows one group of gangsters attempting to appropriate the gold (the ‘grisbi’) stolen by another gang. Du rififi chez les hommes shows a gang carrying out a meticulous theft from a jewellers, after which another gang tries to appropriate the proceeds; trouble (‘rififi') ensues. Bob le flambeur shows a gambler (a ‘flambeur’) whose plan to rob a casino is foiled by the police. All three films are characterised by an interest in the real, ordinary streets of the city, to a degree that sets them apart from the films around them.

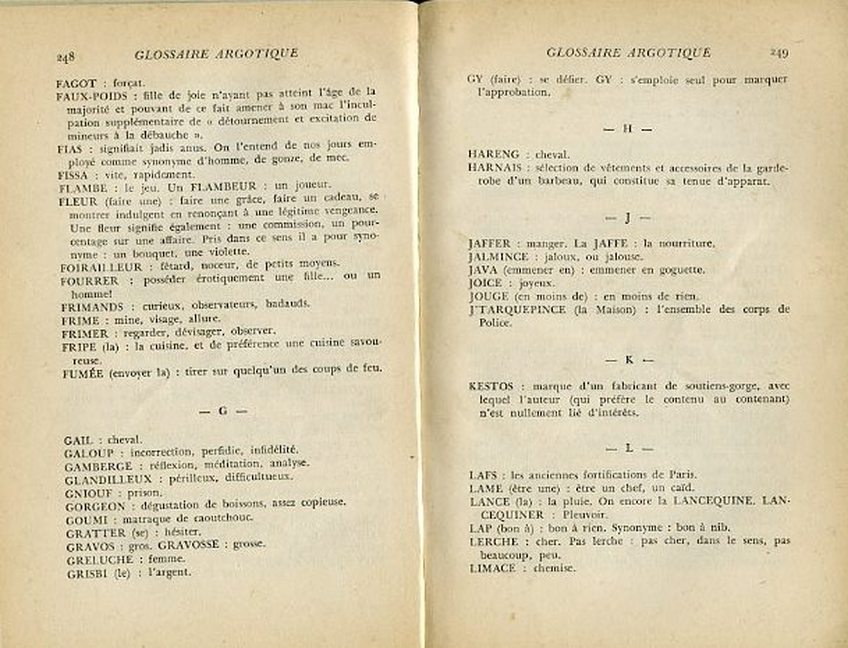

For all three of these films the question of authenticity is central, but it is not the use of real Parisian streets that can alone establish that authenticity. A major factor is the use of language. In their titles the three films signal that they speak the authentic language of the gangster milieu: ‘grisbi’, ‘rififi’ and ‘flambeur’ are slang terms, exotic in their obscurity. The writers of the films – Albert Simonin for Touchez pas au grisbi and Auguste le Breton for Du rififi chez les hommes and Bob le flambeur – were crime novelists who specialised in the argotic style, each claiming special knowledge of the criminal underworld and its private language. This language becomes, in the films, a sign of authenticity, and brings with it a belief that the look, manners and actions of the gangsters represented are also authentic.

Simonin demonstrated the extent of his linguistic knowledge by including in an appendix a glossary of the slang used in Touchez pas au grisbi:

For all three of these films the question of authenticity is central, but it is not the use of real Parisian streets that can alone establish that authenticity. A major factor is the use of language. In their titles the three films signal that they speak the authentic language of the gangster milieu: ‘grisbi’, ‘rififi’ and ‘flambeur’ are slang terms, exotic in their obscurity. The writers of the films – Albert Simonin for Touchez pas au grisbi and Auguste le Breton for Du rififi chez les hommes and Bob le flambeur – were crime novelists who specialised in the argotic style, each claiming special knowledge of the criminal underworld and its private language. This language becomes, in the films, a sign of authenticity, and brings with it a belief that the look, manners and actions of the gangsters represented are also authentic.

Simonin demonstrated the extent of his linguistic knowledge by including in an appendix a glossary of the slang used in Touchez pas au grisbi:

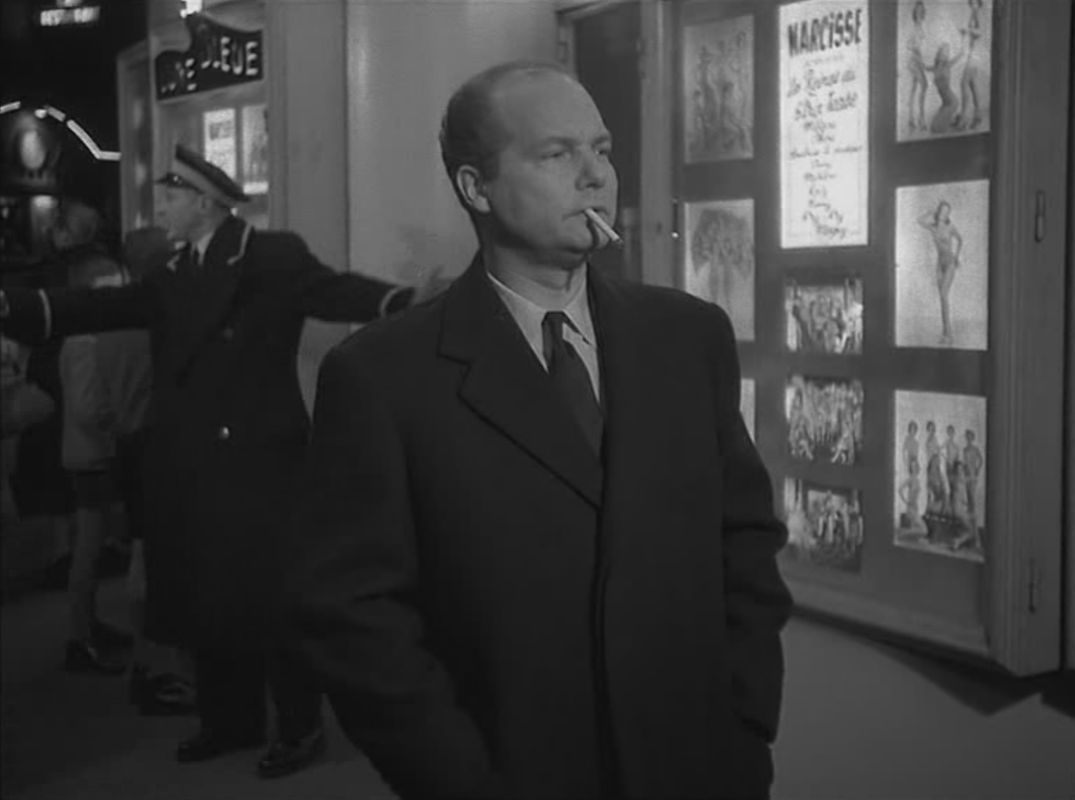

Le Breton demonstrated the extent of his knowledge of the underworld milieu by bringing along some authentic gangsters to be extras in the adaptation of his novel Razzia sur la chnouf - that is Le Breton himself with the hat and cigarette:

(For more on the relation between novels, films and the real underworld of Pigalle, see Patrice Bellon's Pigalle: le roman noir de Paris, pp. 173-81.)

In their three films, Becker, Dassin and Melville raised the standard of the French crime film to a level that few others in the 1950s match. A larger corpus would include, as well as Razzia sur la chnouf and Une balle dans le canon,Kirsanoff's Le Crâneur, Yves Allégret's Quand la femme s'en mêle, Moguy's Le Long des trottoirs, Grangier's Le Désordre et la Nuit, his Le Rouge est mis and Chenal's Rafles sur la ville.

In their three films, Becker, Dassin and Melville raised the standard of the French crime film to a level that few others in the 1950s match. A larger corpus would include, as well as Razzia sur la chnouf and Une balle dans le canon,Kirsanoff's Le Crâneur, Yves Allégret's Quand la femme s'en mêle, Moguy's Le Long des trottoirs, Grangier's Le Désordre et la Nuit, his Le Rouge est mis and Chenal's Rafles sur la ville.

But the core remains the Becker-Dassin-Melville trilogy. Despite his antipathy for gangsters and for the conventions of the gangster genre, all three of these films found favour with Truffaut, whereas those others I have mentioned did not. The New Wave was a cinema of the real, and both Truffaut and Godard would have appreciated in these three films their openness to the real world around them. At the centre of that real world were the streets of Paris.

These films are Paris-centred, but a thorough topographic reading of them would also have to consider the world beyond Paris that they represent: a large part of Bob le flambeur is in Deauville, in and around the casino Bob is planning to rob; in Du rififi chez les hommes the final shoot-out takes place at Saint Rémy les Chevreuse, a small town west of Paris; and the dramatic climax of Touchez pas au grisbi is on the road towards Villennes, another small town west of Paris. However, I shall only be discussing what we see of Paris itself in these films.

Similarly, a topographic reading should turn on the opposition between real places and constructed studio spaces, and mostly in these films that is a distinction between exteriors and interiors. The same kinds of interior recur in these and other films in the genre: hotel rooms, apartments, restaurants and cafés. Some of these interiors may be real places, but most are studio constructions. Though we are interested here in the real streets of Paris, one type of interior is central to the topography of these films: the nightclub or, more precisely, the nightclubs of Pigalle.

These films are Paris-centred, but a thorough topographic reading of them would also have to consider the world beyond Paris that they represent: a large part of Bob le flambeur is in Deauville, in and around the casino Bob is planning to rob; in Du rififi chez les hommes the final shoot-out takes place at Saint Rémy les Chevreuse, a small town west of Paris; and the dramatic climax of Touchez pas au grisbi is on the road towards Villennes, another small town west of Paris. However, I shall only be discussing what we see of Paris itself in these films.

Similarly, a topographic reading should turn on the opposition between real places and constructed studio spaces, and mostly in these films that is a distinction between exteriors and interiors. The same kinds of interior recur in these and other films in the genre: hotel rooms, apartments, restaurants and cafés. Some of these interiors may be real places, but most are studio constructions. Though we are interested here in the real streets of Paris, one type of interior is central to the topography of these films: the nightclub or, more precisely, the nightclubs of Pigalle.

Setting the action in Pigalle gives to a crime film an authenticity that is not just topographical but also discursive – from novels and newspapers the public knew that Pigalle was the natural habitat of the Paris gangster. Films like 56 rue Pigalle (1949) La Môme Pigalle (1955) signal in their titles the criminal milieu in which the fiction will unfurl, but whatever the film’s name it is easy to establish this setting. All it takes is a shot of the neon signs on the place Pigalle, the visually distinctive display of its famous cabaret names, or even just a view of Le Pigall’s, with its memorable slogan: ‘Les nus les plus osés du monde’, ‘the world’s most daring nudes’.

The names of Pigalle nightclubs constitute a world of fantasy and imagination – Narcisse, Sphinx, Eve, Cupidon, Les Naturistes, La Lune Rousse – but the signs displaying them belong to a real and recognisable world. The fiction of these films take its characters from the real streets of Pigalle into an invented space, typically by bringing the protagonist to the door of a real nightclub and then showing him, on the other side, in a studio reconstruction. Often there is a distinctive shift in the tones of the image, as we pass from an exterior illuminated by electric signs in the street to an interior illuminated by the full panoply of studio lighting.

In Du rififi chez les hommes the protagonist is shown crossing the rue Pigalle; behind him against the night sky we can read the names of Le Grand Jeu, Le Can-Can and Chez Moune le Fétichiste. He reaches the door of a nightclub at number 59, actually the Piccadilly, but as a sign of the passage from real world to fiction the name of the club is changed to L’Age d’Or:

In Du rififi chez les hommes the protagonist is shown crossing the rue Pigalle; behind him against the night sky we can read the names of Le Grand Jeu, Le Can-Can and Chez Moune le Fétichiste. He reaches the door of a nightclub at number 59, actually the Piccadilly, but as a sign of the passage from real world to fiction the name of the club is changed to L’Age d’Or:

The nightclub in Touchez pas au grisbi is, similarly, given a false name at the point where we pass from a real street into a studio-made fiction. The ‘Mystific’ is actually the Fétiche de Paris, at 2 rue Frochot:

Again there will be a contrast between the dimness of the exterior at night time and the brightness of the nightclub’s interior.

Bob le flambeur plays with this disposition by having its protagonist on the street outside in the peculiar light of daybreak, and then enter the studio-constructed nightclub, where men are gambling in near darkness. We see no name for the nightclub in Bob le flambeur, though its exterior is shown to be on the rue Pigalle. Before the protagonist enters we see a part of a sign reading ‘NUS’, nudes, not a name but an emblematic designation of the kind of place it is (the sign is actually on the Pigall’s nightclub, across the street, where the nudes are the world’s most daring).

Bob le flambeur plays with this disposition by having its protagonist on the street outside in the peculiar light of daybreak, and then enter the studio-constructed nightclub, where men are gambling in near darkness. We see no name for the nightclub in Bob le flambeur, though its exterior is shown to be on the rue Pigalle. Before the protagonist enters we see a part of a sign reading ‘NUS’, nudes, not a name but an emblematic designation of the kind of place it is (the sign is actually on the Pigall’s nightclub, across the street, where the nudes are the world’s most daring).

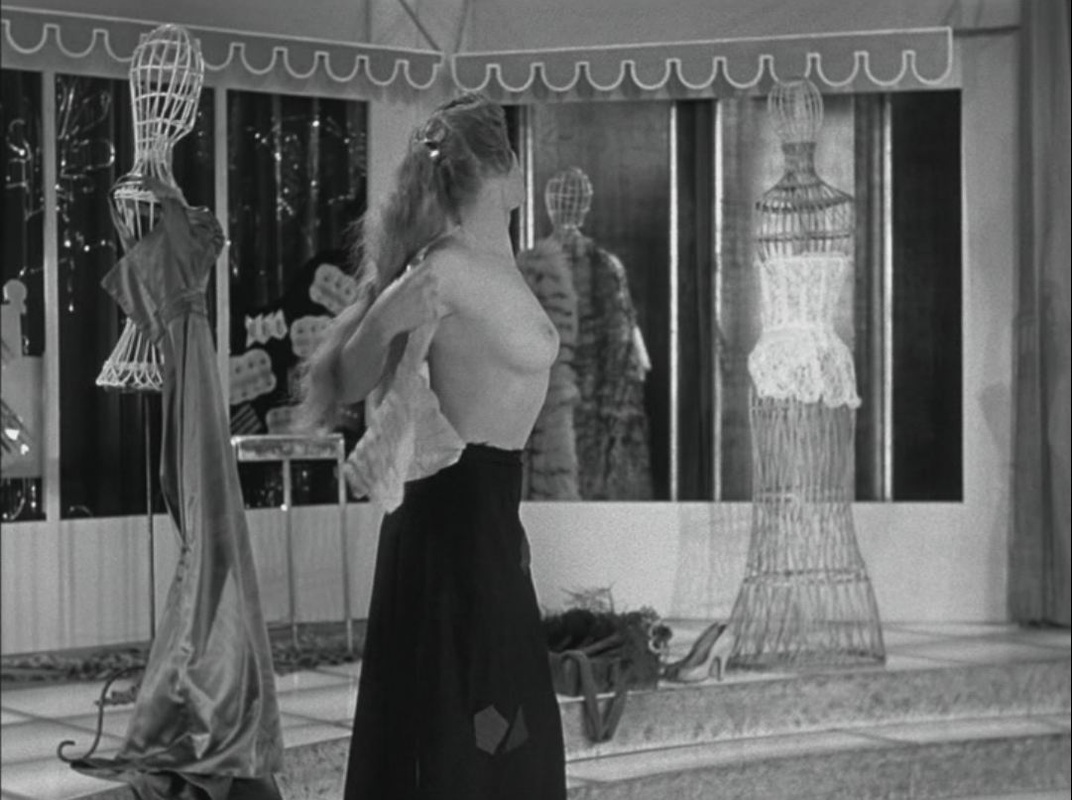

Curiously, though the expectation would be that in a Pigalle nightclub the floorshow would include nude dancers, there is none in any of these three films. This was not a question of censorship, since nude acts featured in French films of this period with impunity (e.g. Femmes de Paris, En effeuillant la marguerite, Le Long des trottoirs).

Despite displaying in detail the spectacle within the nightclub, Touchez pas au grisbi, Du rififi chez les hommes and Bob le flambeur all avoid the authenticity of naked bodies.

An interesting contrast can be drawn here with a crime film that Godard rated alongside Touchez pas au grisbi and Du rififi chez les hommes, Pierre Chenal’s Rafles sur la ville (1957), which does feature Pigalle-style nudity:

An interesting contrast can be drawn here with a crime film that Godard rated alongside Touchez pas au grisbi and Du rififi chez les hommes, Pierre Chenal’s Rafles sur la ville (1957), which does feature Pigalle-style nudity:

Reviewing the film in Cahiers du cinéma, Godard singled it out for its authenticity:

This routine little thriller is most engaging. Personally, I rate it third in my list, after Le Grisbi and Rififi. Why? Simply because French cops are for once shown as ordinary people with the same reactions as anyone else - trying to make a colleague’s wife, for instance, if she happens to be pretty. It doesn’t happen often, but here, given a hackneyed story, Auguste Le Breton has written some excellent dialogue. All the scenes between the inspector (Michel Piccoli, excellent) and the charming chick from the 16th (Danick Patisson, perfect) have an accuracy of tone which cuts right across the routine production. It is all too rarely in a French film that one finds characters who talk simply for the pleasure of it and not to tell us something.[…] ‘A real film’, says the publicity. I say, ‘A real film.’ (Jean-Luc Godard, ‘Rafles sur la ville’, in Godard on Godard: Critical Writings, p.73.)

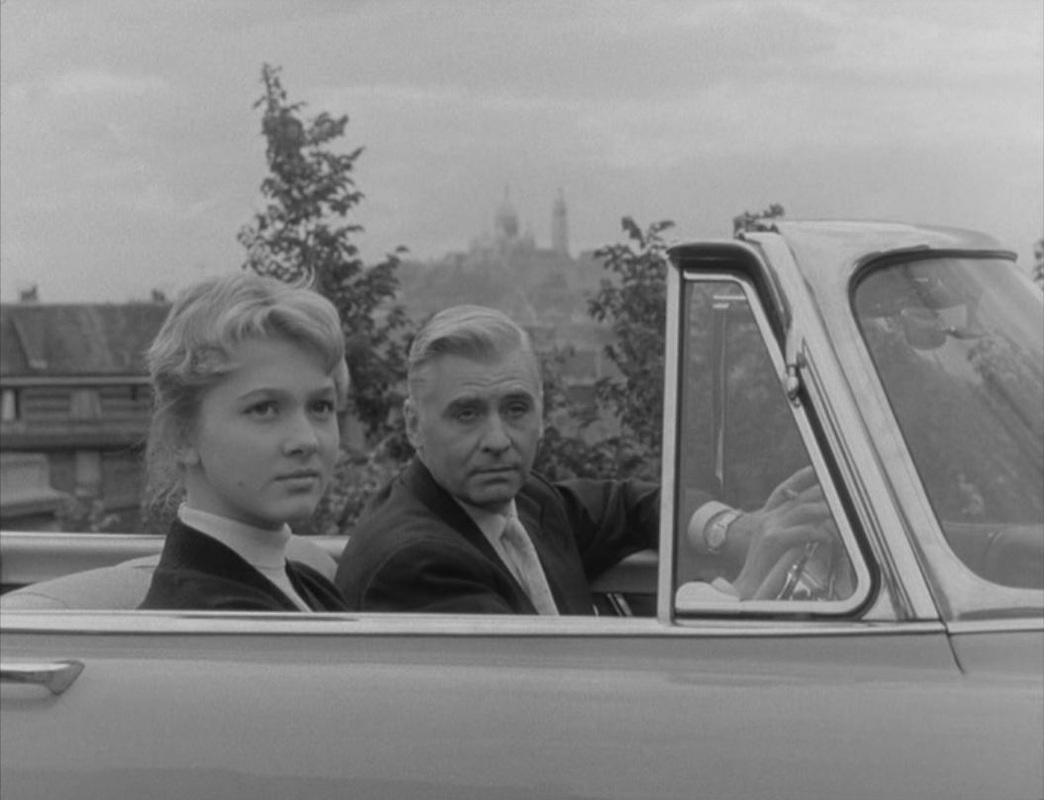

In praising the dialogue of the film for its accuracy of tone, Godard anticipates one of the virtues of the New Wave, insofar as the language used is ordinary and natural. He is less interested in the film’s gritty realism, which includes the incorporation of authentic striptease acts from the cabarets of Pigalle. When Godard presents striptease in one of his own films, Une femme est une femme (1961), he avoids Pigalle and makes no attempt to represent authentic performance. In his review, Godard also avoids considering how Chenal shows the streets of Paris, but in A bout de souffle he will pay homage to Rafles sur la ville when he stages a conversation on the boulevard du Montparnasse (the scene I described at the beginning of this piece). In Chenal’s film, two men and a woman have a conversation by a parked car, just across the street from where, in Godard’s film, two men and a woman have a conversation by a parked car:

This routine little thriller is most engaging. Personally, I rate it third in my list, after Le Grisbi and Rififi. Why? Simply because French cops are for once shown as ordinary people with the same reactions as anyone else - trying to make a colleague’s wife, for instance, if she happens to be pretty. It doesn’t happen often, but here, given a hackneyed story, Auguste Le Breton has written some excellent dialogue. All the scenes between the inspector (Michel Piccoli, excellent) and the charming chick from the 16th (Danick Patisson, perfect) have an accuracy of tone which cuts right across the routine production. It is all too rarely in a French film that one finds characters who talk simply for the pleasure of it and not to tell us something.[…] ‘A real film’, says the publicity. I say, ‘A real film.’ (Jean-Luc Godard, ‘Rafles sur la ville’, in Godard on Godard: Critical Writings, p.73.)

In praising the dialogue of the film for its accuracy of tone, Godard anticipates one of the virtues of the New Wave, insofar as the language used is ordinary and natural. He is less interested in the film’s gritty realism, which includes the incorporation of authentic striptease acts from the cabarets of Pigalle. When Godard presents striptease in one of his own films, Une femme est une femme (1961), he avoids Pigalle and makes no attempt to represent authentic performance. In his review, Godard also avoids considering how Chenal shows the streets of Paris, but in A bout de souffle he will pay homage to Rafles sur la ville when he stages a conversation on the boulevard du Montparnasse (the scene I described at the beginning of this piece). In Chenal’s film, two men and a woman have a conversation by a parked car, just across the street from where, in Godard’s film, two men and a woman have a conversation by a parked car:

I have argued that Pigalle nightclubs in French gangster films are a peculiar locale where reality and fiction meet, where real exteriors are conjoined with invented interiors. When it comes to its nightclub, however, Rafles sur la ville deviates both from is own tendency to use real exteriors and from the norms of the genre to which it belongs. Rather than show establishing shots of the place Pigalle and then constructing the interior in the studio, the exterior space is entirely studio-constructed. The street, the nearby cafés and bars and the nightclub itself are all false, and no specific part of Paris is identified as the locale. The night club is called ‘Le Pégase’ and has a slogan painted on the wall that alludes explicitly to that of its near homophone Le Pigall’s: ‘Les plus beaux nus in the world’.

The specific re-imagining of Pigalle in this film is unusual, but a number of other French noir films from this period use this kind of studio-constructed exterior, whereby they can better manipulate lighting and staging. In so doing they connect with the tradition of French poetic realism, as here, in Razzia sur la Chnouf:

The films in the genre by Becker, Dassin and Melville stand out against this background because their streets are not studio confections. Nonetheless, we can distinguish how each film registers the real streets in front of its camera, and configures differently the topography of the city.

There are several modes of filming outside of the studio. At one extreme is the street-level view, with its roadways and pavements, pedestrians and motor-vehicles, its walls, windows and doorways, its benches, lamp-posts, phone booths, newsstands and métro entrances, its shopfronts and cafés. This level includes views of the street filmed from inside a car, a mode that smaller cameras allowed the New Wave to exploit to the full. In '50s noir the artifice of back projection is the norm, as in Touchez pas au grisbi, with several passages that show the streets of Paris projected behind or in front of its characters in the studio as they pretend to drive:

There are several modes of filming outside of the studio. At one extreme is the street-level view, with its roadways and pavements, pedestrians and motor-vehicles, its walls, windows and doorways, its benches, lamp-posts, phone booths, newsstands and métro entrances, its shopfronts and cafés. This level includes views of the street filmed from inside a car, a mode that smaller cameras allowed the New Wave to exploit to the full. In '50s noir the artifice of back projection is the norm, as in Touchez pas au grisbi, with several passages that show the streets of Paris projected behind or in front of its characters in the studio as they pretend to drive:

The climactic drive across Paris in Du rififi chez les hommes is able to include real views from the car because it is a big American convertible (a 1950 Oldsmobile Futuramic, according to the IMCDB), with more room for the camera:

The camera’s accumulation of ordinary details, perceived as someone would if they were actually on the street, would give the New Wave its basic realist foundations. It also gave such foundations to these films by Becker, Dassin and Melville, in striking contrast to, for example, Razzia sur la chnouf, a film that is superficially similar but in which almost every street-level view is a studio construction:

At the other extreme is the panoramic view, embracing the city from a high vantage point, taking in as it pans other high vantage points that serve as monumental markers of place: the Eiffel Tower, the Sacré Coeur, the Arc de Triomphe, Notre Dame, the Panthéon. Between these two extremes is the city perceived by the raised gaze, the perspective of the tourist who looks up to take in the scale of monumental buildings. Such views are rare in these three films: near the beginning of Bob le flambeur we look up at the Sacré Coeur from the street immediately in front of it, but that is an establishing view that is quickly superseded; during the climactic car ride across Paris in Du rififi chez les hommes the camera angles up to admire the Arc de Triomphe, but that is the viewpoint of a child in the car:

In Touchez pas au grisbi there are no such views of landmarks - nothing, after the panorama behind the credits, to tell the tourist that this is Paris:

Also, somewhere between the extremes of street level and panorama, there is the view from a bridge or riverside. This is street level, but shares with the panorama a degree of recession into the distance, like a landscape, and can take in the scale of large buildings by the river’s edge. Du rififi chez les hommes has two or three views of this kind, Touchez pas au grisbi and Bob le flambeur do not:

One last intermediary view is the angled shot down onto a street from a window, a small-scale panorama that is usually motivated by the narrative: in Touchez pas au grisbi, someone is watching for the police to arrive, or for gangsters to leave; in Du rififi chez les hommes, the robbers observe the routine of the streets around the jewellers they are targetting. In Bob le flambeur these views are not narratively motivated, but simply allow us to observe Bob, looking down onto the place Pigalle as he walks home at dawn, or down onto the avenue Junot as he drives off in his Plymouth Belvedere:

Coming last of the three, Bob le flambeur is in a position to reference elements of the other two. Melville will develop this intertextual tendency in later films, when, for example, he puts Alain Delon as Le Samourai (1967) in the same spaces on the Champs-Elysées that Jean-Paul Belmondo had occupied in A bout de souffle (see here), or when in Le Cercle rouge (1970) he recreates the staging of the robbery in Du rififi chez les hommes (in both films the target is a jeweller’s on the place Vendôme). In Bob le flambeur he declares a difference from Du rififi chez les hommes in the rendering of the city itself, very simply by confining his film to a very restricted locale, only once showing Bob in a part of Paris that is not Montmartre (see here). Dassin, by contrast, had taken great pleasure in discovering different districts of the city, spreading the action north, east, south and west, such that Du rififi chez les hommes becomes a catalogue of distinctive views. This approach is typical of a non-native filmmaker in a new city; Dassin had done the same five years earlier in his London-set noir Night and the City.

The credits of Touchez pas au grisbi roll over a panoramic pan right to left over the city. At first the rooftops are anonymous, but the Sacré Coeur slowly comes into frame then passes out of frame, and the shot closes by tilting down to show the Moulin Rouge on the north side of the boulevard de Clichy. The camera is somewhere high up on the south side of that boulevard, looking north, as if its back were turned on the rest of Paris:

The credits of Touchez pas au grisbi roll over a panoramic pan right to left over the city. At first the rooftops are anonymous, but the Sacré Coeur slowly comes into frame then passes out of frame, and the shot closes by tilting down to show the Moulin Rouge on the north side of the boulevard de Clichy. The camera is somewhere high up on the south side of that boulevard, looking north, as if its back were turned on the rest of Paris:

The opening of Bob le flambeur references explicitly this opening, with a right-to-left pan over the city, though this time the camera is to the north, in front of the Sacré Coeur, looking south:

The development from each of these two openings tells the difference between how the two films approach the city. Grisbi cuts from the panorama to the (studio-constructed) interior of a restaurant, from which we emerge eventually onto an anonymous, though real, street. That will be the pattern of the film as a whole: alternation of interiors and streets, with very few of these streets identifiable – two are even given false names, as if to detach them from their cartographic reality.

By contrast, Bob le flambeur follows its panoramic pan with a close-up shot of the Sacré Coeur, a view of the funicular railway heading down towards Pigalle then, after the Pigalle métro station that localises us cartographically, a succession of signs that place us among the clichés of Pigalle: ‘Les Naturistes’, ‘Eve’, ‘Aux Pierrots’, ‘Narcisse’, ‘Le Grand Jeu’, ‘Le Tabarin’, ‘Le Can Can’ - the names of famous cabarets. Finally we cut to an interior, studio-made, and though Bob le flambeur like Grisbi alternates such interiors with real streets, every street in Bob le flambeur is identifiable. When Bob brings a young woman to his apartment building on the avenue Junot, he make sure she and we remember its number, 36 (‘like the Quai des Orfèvres… police headquarters’):

By contrast, Bob le flambeur follows its panoramic pan with a close-up shot of the Sacré Coeur, a view of the funicular railway heading down towards Pigalle then, after the Pigalle métro station that localises us cartographically, a succession of signs that place us among the clichés of Pigalle: ‘Les Naturistes’, ‘Eve’, ‘Aux Pierrots’, ‘Narcisse’, ‘Le Grand Jeu’, ‘Le Tabarin’, ‘Le Can Can’ - the names of famous cabarets. Finally we cut to an interior, studio-made, and though Bob le flambeur like Grisbi alternates such interiors with real streets, every street in Bob le flambeur is identifiable. When Bob brings a young woman to his apartment building on the avenue Junot, he make sure she and we remember its number, 36 (‘like the Quai des Orfèvres… police headquarters’):

The cafés and restaurants Bob frequents are all real, with their names unchanged: ‘Le Carpeaux’ is a café at 17 rue Carpeaux; ‘Le Mandarin’ is a chinese restaurant at 6 rue de Douai and the Pile ou Face is a bar next door. Le Carpeaux is now a restaurant, and Le Mandarin has turned Japanese, but the Pile ou Face is still there, more or less intact:

All three of these films use the real streets of Paris as a means of establishing authenticity, even if to differing degrees and in different ways. Touchez pas au grisbi is the most detached from the reality of the city because its aesthetic, as Truffaut identifies it, is one of economy, a rejection of the picturesque (‘Touchez pas au grisbi’ , in The Films In My Life, p. 180).We see seven different Paris locations, most of them anonymous, all of them ordinary: the city is not on display, its identity is disguised. To the invented street names (‘rue Alphonse Allais’, ‘rue des Détroits’) we can add the ‘Hôtel Moderna’, which is actually the Perfect Hotel, in Pigalle (at 39 rue Rodier – it is still there). The ‘Bouche’ restaurant is a mix of studio construction and the real exterior of a dance hall in Montparnasse, on the rue Blomet. This had been famous in the 1920s as the ‘Bal Blomet’ or ‘Bal nègre’, centre of West Indian jazz culture in Paris (see here). The film makes nothing of this historic association, and doesn’t even signal that this area of the film’s action is across the city from Pigalle. Unlike Simonin’s novel, the film is not interested in the territorial differences between one part of Paris and another.

In Du rififi chez les hommes the city is a spectacle, with twenty-five different Paris locations, topographically diverse, visually varied, and all identifiable (see here).

For Bob le flambeur the city is that small part of it that is Montmartre. When Bob is not there but on the other side of Paris, behind him we see the Sacré Coeur, to remind us that for him only Montmartre is important. This view of Montmartre from the place he is supposed to be is an impossible view,and is constructed through the montage of different locations. At this point the film mythologises Montmartre, just as it mythologises Bob:

It is too easy to say that a film which makes complex and illuminating use of the place it occupies is somehow ‘about’ that place. Truffaut argues cogently that Touchez pas au grisbi is actually about growing old, and identifies as a key moment the scene where we see Jean Gabin in his pyjamas, getting ready for bed. Du rififi chez les hommes and Bob le flambeur are also about ageing (we also see Bob in his pyjamas), and in a real sense the city in each of these films is just a backdrop to the human drama:

But films don’t just tell stories about characters: they also document the objects around them (their clothes, their cars, their cigarettes), and they document the places in which those characters act, not only the real streets down which they walk but the invented places that they walk to and from. And films don’t just document these things, they reconfigure them. Paris in the films I have discussed is shown for what it is, but also for how it can be remembered, and for how it could be imagined. The same can be said for the Paris of the French New Wave, and I would argue that it is from Becker, Dassin and Melville that not only Godard and Truffaut but also Rivette, Chabrol and (perhaps) Rohmer learned how to film the city. Because of this, the Paris of ‘50s film noir is worth our interest both as a thing itself and as a part of the history of cinema.

Films discussed

- 56 rue Pigalle (1949 Willy Rozier)

- A bout de souffle (Jean-Luc Godard 1960)

- Adama est... Eve (René Gaveau 1954)

- Bob le flambeur (Jean-Perre Melville 1956)

- Le Crâneur (Dimitri Kirsanoff 1955)

- Le Désordre et la Nuit (Gilles Grangier 1958)

- Du rififi chez les hommes (Jules Dassin 1955)

- En effeuillant la marguerite (Marc Allégret 1956)

- Femmes de Paris (Jean Boyer 1953)

- Le Long des trottoirs (Léonide Moguy 1957)

- La Môme Pigalle (Alfred Rode 1955)

- Quand la femme s’en mêle (Yves Allégret 1957)

- Paris Clandestin (Walter Kapps 1957)

- Rafles sur la ville (Pierre Chenal 1957)

- Razzia sur la chnouf (Henri Decoin 1955)

- Le Rouge est mis (Gilles Grangier 1957)

- Tirez sur le pianiste (François Truffaut)

- Touchez pas au grisbi (Jacques Becker 1954)

- LA Tournée des Grands Ducs (André Pellenc 1953)

- Une Balle dans le canon (Michel Deville 1958)

- Une femme est une femme (Jean-Luc Godard 1961)

References

- Patrice Bellon, Pigalle: le roman noir de Paris (Paris: Hoëbeke, 2004)

- Jean-Luc Godard, ‘Rafles sur la ville’ [1957], in Godard on Godard: Critical Writings (London: Viking Press, 1972)

- François Truffaut, ‘Touchez pas au grisbi’ [1954], in The Films In My Life (New York: Da Capo, 1994)

- François Truffaut, Interviews, ed. Ronald Bergan (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi 2008)

- Ginette Vincendeau, Jean-Pierre Melville: an American in Paris (London: BFI, 2003)