Hatot-Breteau: two Lumière filmmakers in Paris c.1897

|

This post was just meant to be looking at the Paris exteriors of a handful of films made by Georges Hatot (1876-1959) and Gaston Breteau (1859-1909) for the Lumière company in 1897, but it ended up going a little further than that.

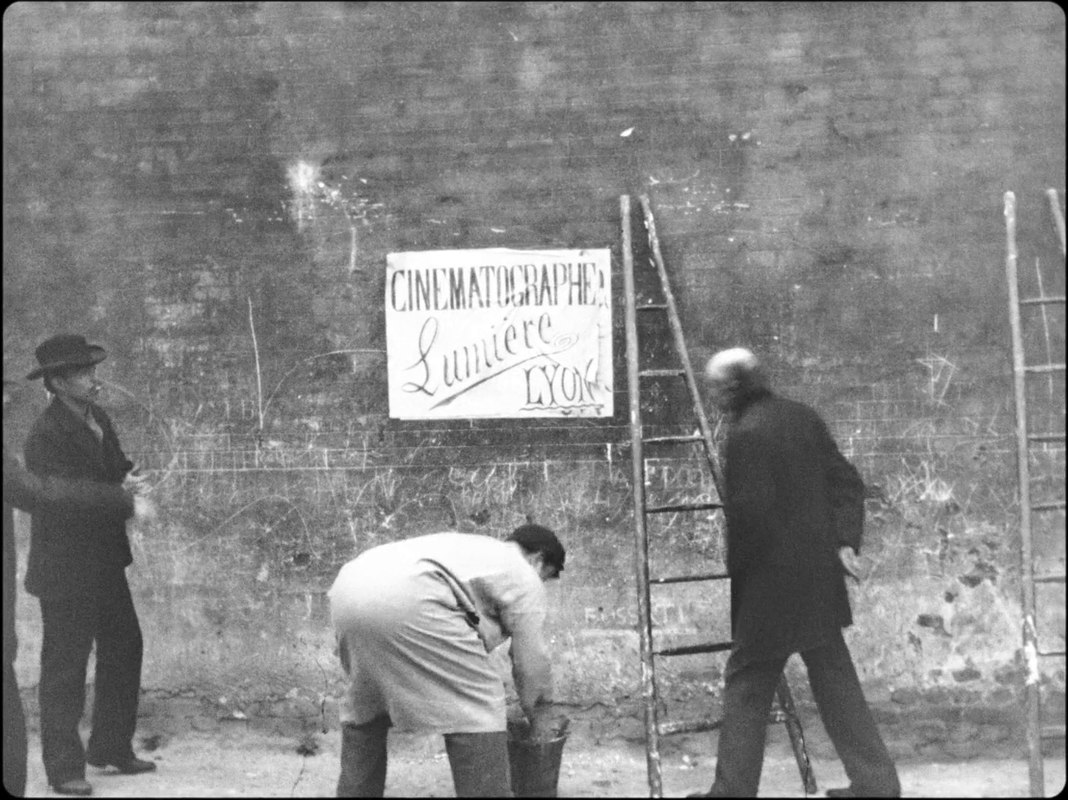

The websites of the CNC Archives and the Catalogue Lumière list twenty-nine of these Hatot-Breteau films. Only seven are set and shot in exteriors, including Colleurs d'affiches (right), a film for which I do not expect to identify the location. |

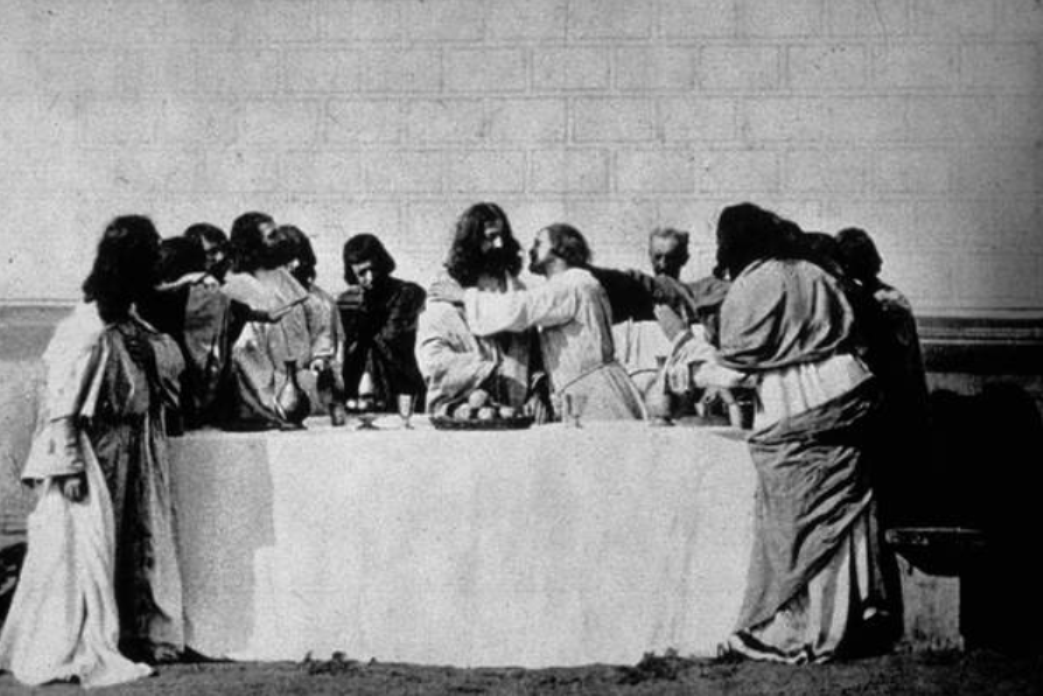

In 1898 Hatot and Breteau made a few more films for the Lumière company, including a thirteen-tableaux Vie et Passion de Jésus-Christ. They also made a Christ-Passion for Gaumont in 1898, as well as some other films. Around that time Breteau also made a Christ-Passion for Pathé - he was 'le Christ éternel', Hatot said of him in 1948.

There are a few films that Hatot may have erroneously laid claim to, and others that might reasonably be ascribed to him or to Breteau (see Appendixes 2 and 3, below).

The credits of Hatot and Breteau's Lumière films often give Alexandre Promio as camera operator and Marcel Jambon as set designer. In his book on Promio, Jean-Claude Seguin refers to them as 'une équipe de tournage', a collaborative team that was led by Promio. I find this view particularly problematic regarding Jambon, and also find that Seguin overstates Promio's importance as auteur of these films, reducing the rôles of Hatot and Breteau. In this post I have tried to avoid auteurism (though I do end up saying that you can know an auteur by the décors he keeps).

There are a few films that Hatot may have erroneously laid claim to, and others that might reasonably be ascribed to him or to Breteau (see Appendixes 2 and 3, below).

The credits of Hatot and Breteau's Lumière films often give Alexandre Promio as camera operator and Marcel Jambon as set designer. In his book on Promio, Jean-Claude Seguin refers to them as 'une équipe de tournage', a collaborative team that was led by Promio. I find this view particularly problematic regarding Jambon, and also find that Seguin overstates Promio's importance as auteur of these films, reducing the rôles of Hatot and Breteau. In this post I have tried to avoid auteurism (though I do end up saying that you can know an auteur by the décors he keeps).

1/ locations

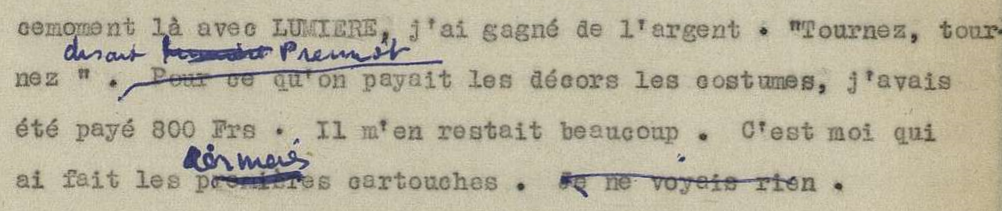

In 1948 Hatot was interviewed by Henri Langlois and Musidora about, among many things, the films he made for the Lumière company. The transcripts of these interviews are available online here and here, and I have used them, as well as the films themselves, as a reference point in this post.

I am also indebted to the excellent GRIMH, le Groupe de réflexion sur l'image dans le monde hispanique, for a wealth of information assembled on Hatot, Breteau, Promio and Jambon, and more generally on the first decade of cinema.

|

The 1948 interviews with Hatot were very approximately transcribed and it sometimes takes some deciphering to work out to what or whom Hatot is referring.

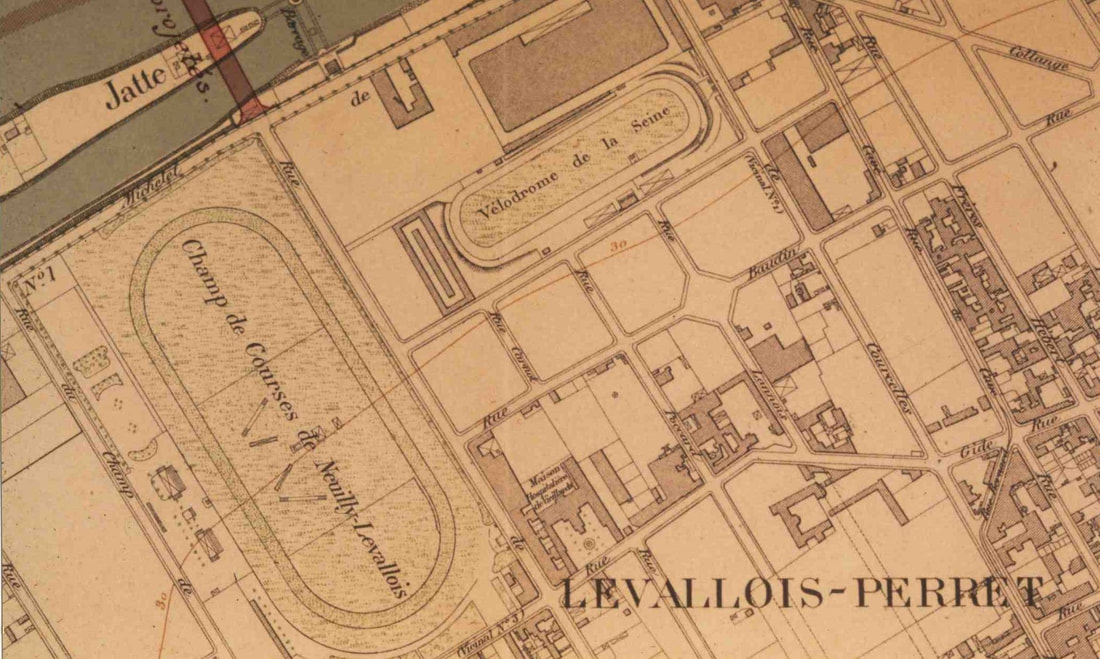

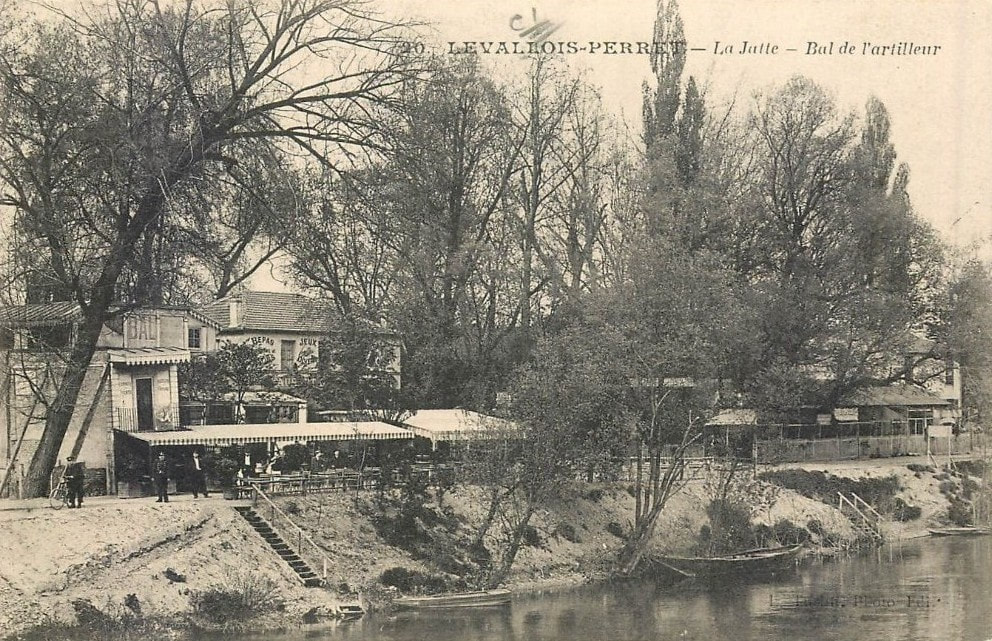

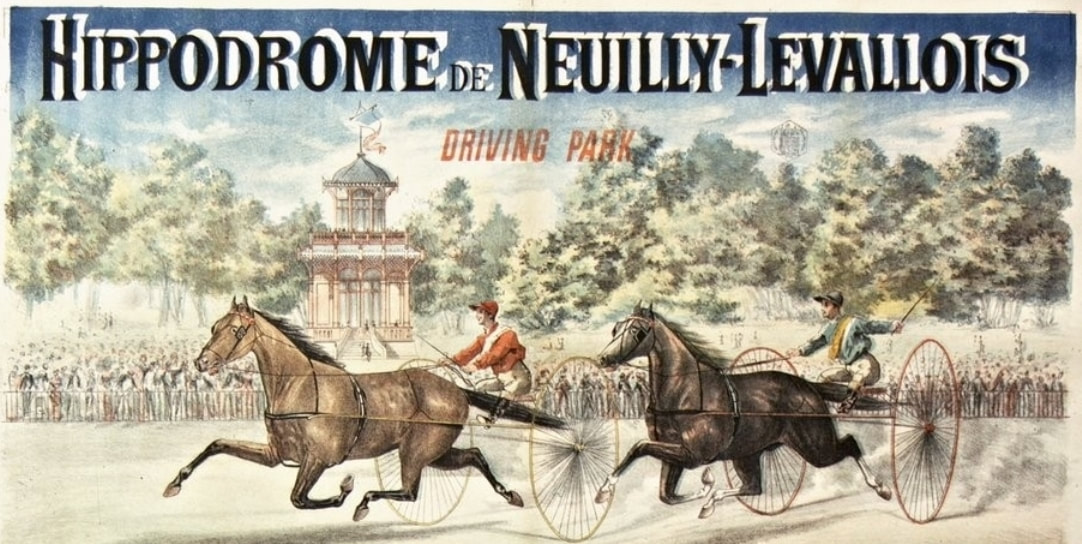

The first films Hatot and Breteau made were La Mort de Marat and Napoléon et la sentinelle, the one at the Bal des Artilleurs on the Ile de la Grande Jatte, the other at the nearby Neuilly-Levallois race course: |

Though for the Napoleon film it may not look like it, both of these are sets, backdrops put up in an open space. Probably for these, as for the rest of the films they made that year, Promio operated the camera. The films were made here because it was near the home of Madame Lafont, their intermediary with the Lumière company. Her husband, Monsieur Lafont, apparently acted in some of the films.

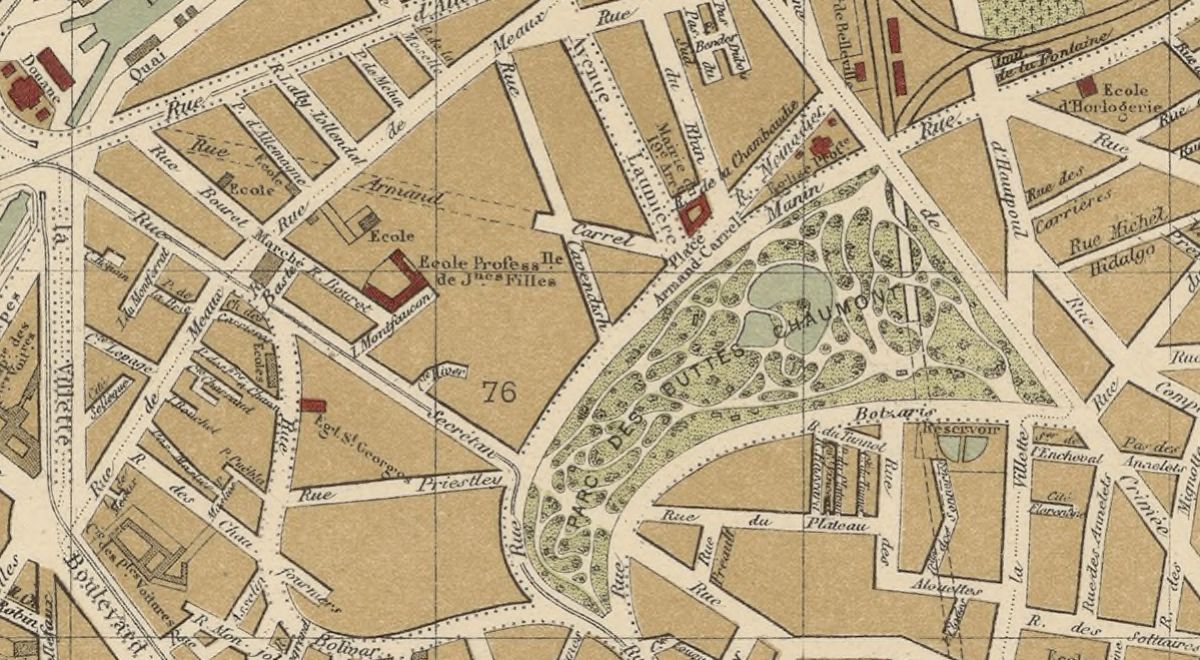

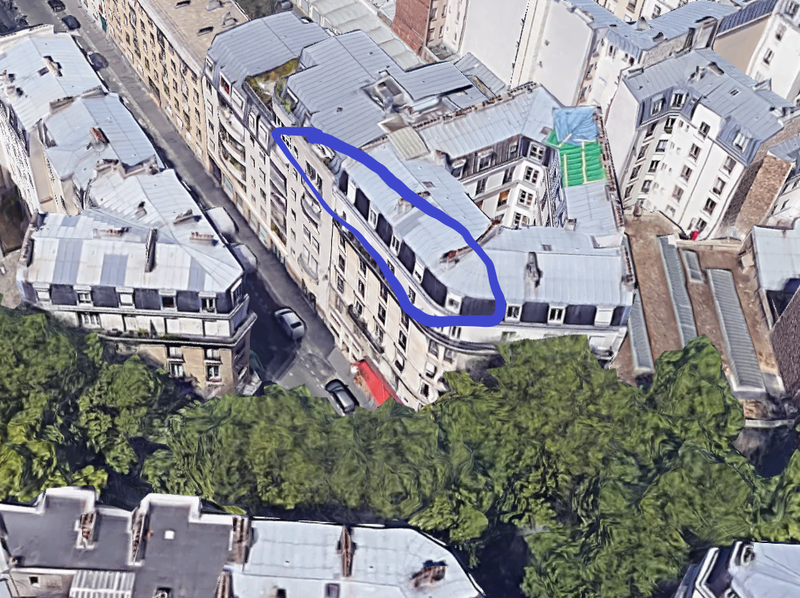

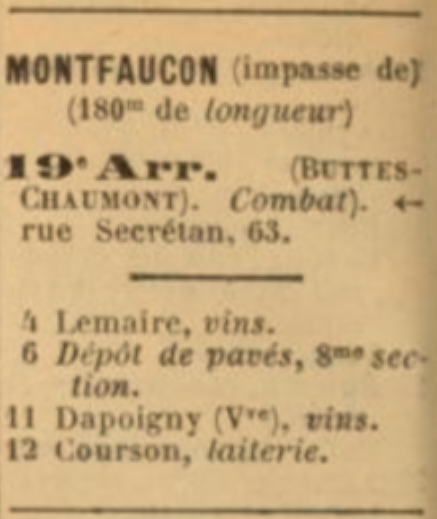

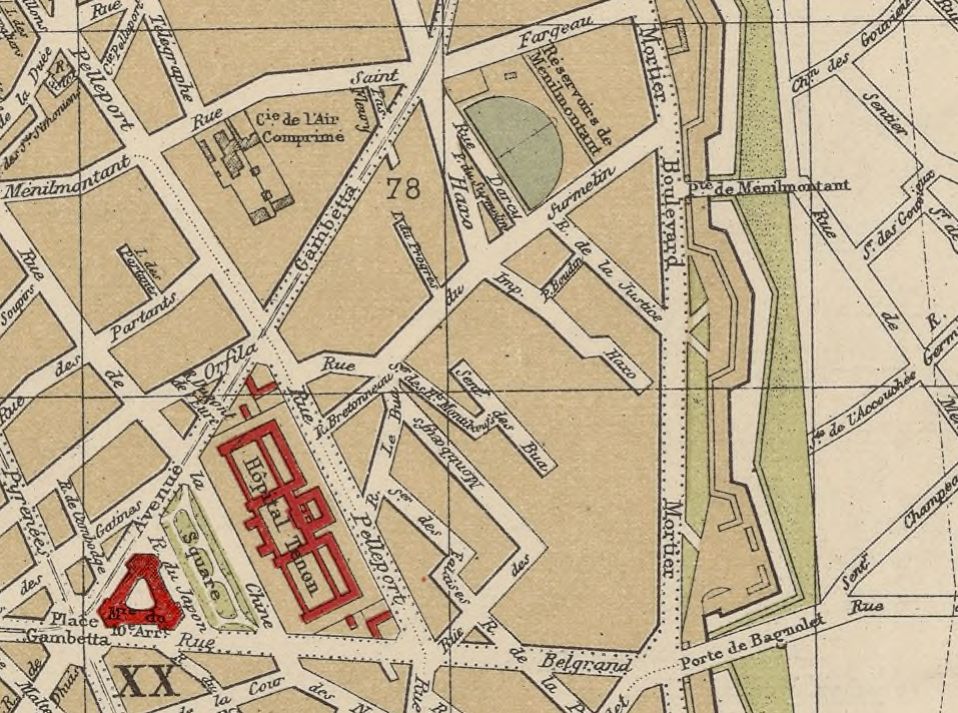

At some point Hatot and Breteau moved their base across Paris, to a site near the Buttes Chaumont, where a cowkeeper whom Hatot knew let them use some of his land. Courson's dairy was at 12 Impasse de Montfaucon, centre-left on the map below:

I have found no photograph of the Impasse de Montfaucon at the time, but below right is where it joined the Rue (now Avenue) Secrétan. (A few doors down at no. 73, just before the Cité Hiver, was Marcel Jambon's workshop.)

|

Hatot says the site used was at the end of the impasse and that it backed onto the buttes. This doesn't mean the Parc des Buttes Chaumont, but the not-yet-developed part of the hills that earlier had been quarried for chalk. Hatot says that the cowkeeper used the buttes as pasture for his cows, a practice still evident ten years later in the Gaumont production Un achat embarrassant (right). These may be Courson's cows, but other local nourisseurs also took their cows to the buttes for pasture: |

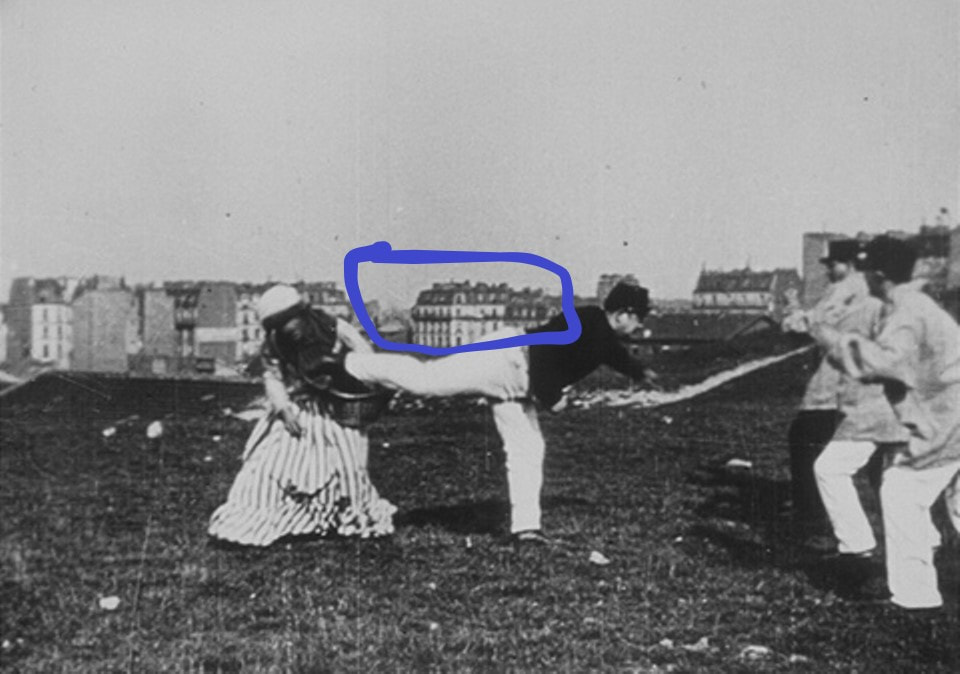

Four of Hatot's exterior-shot films were made on open land that I at first thought (and, unfortunately, stated in a published essay) was part of the fortifications:

The last of these, La Défense du drapeau, with no buildings close by, could well be on the fortifications, as could the Lumière films of Sri Lankan performers from September 1897, in what looks like the same place:

For the other three I can now see that they were made on the buttes. The building highlighted here, in Le Charpentier maladroit, is on the corner of Rue Cavendish and Rue Armand Carrel:

And highlighted here, in Les Boxeurs et le spectateur trop curieux puni, is the corner of Avenue de Laumière and Rue de Meaux:

|

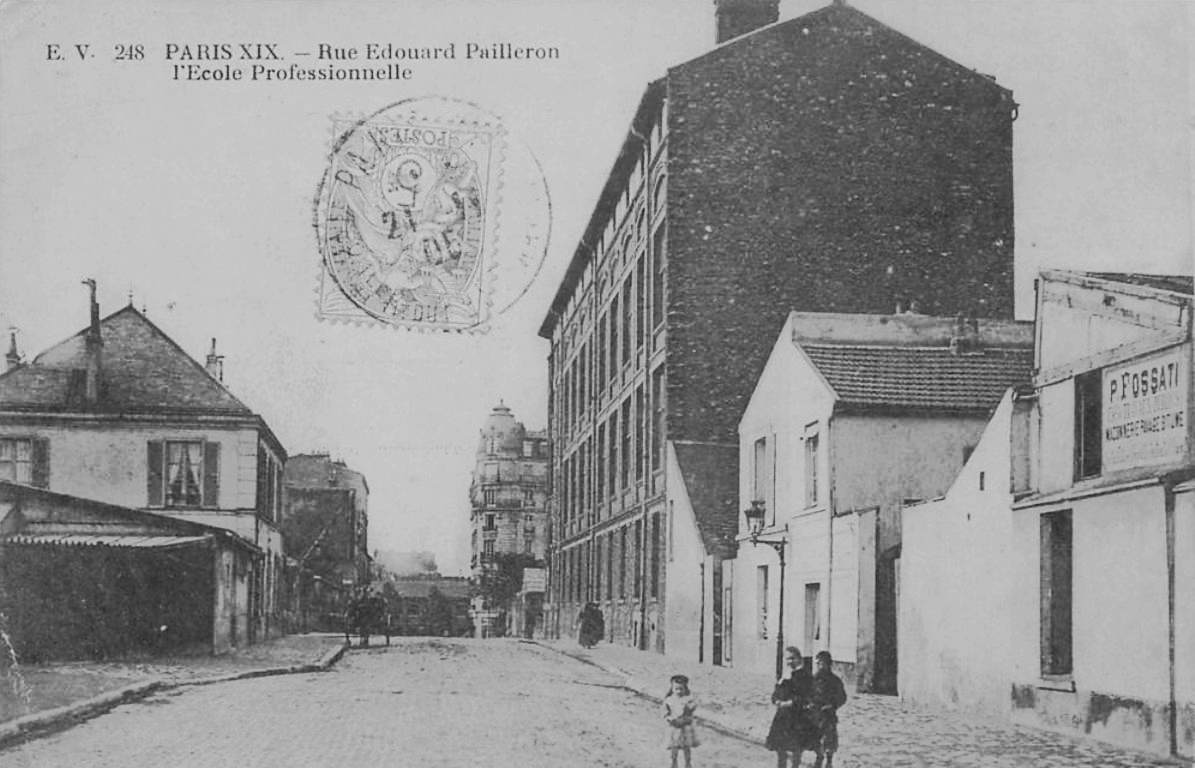

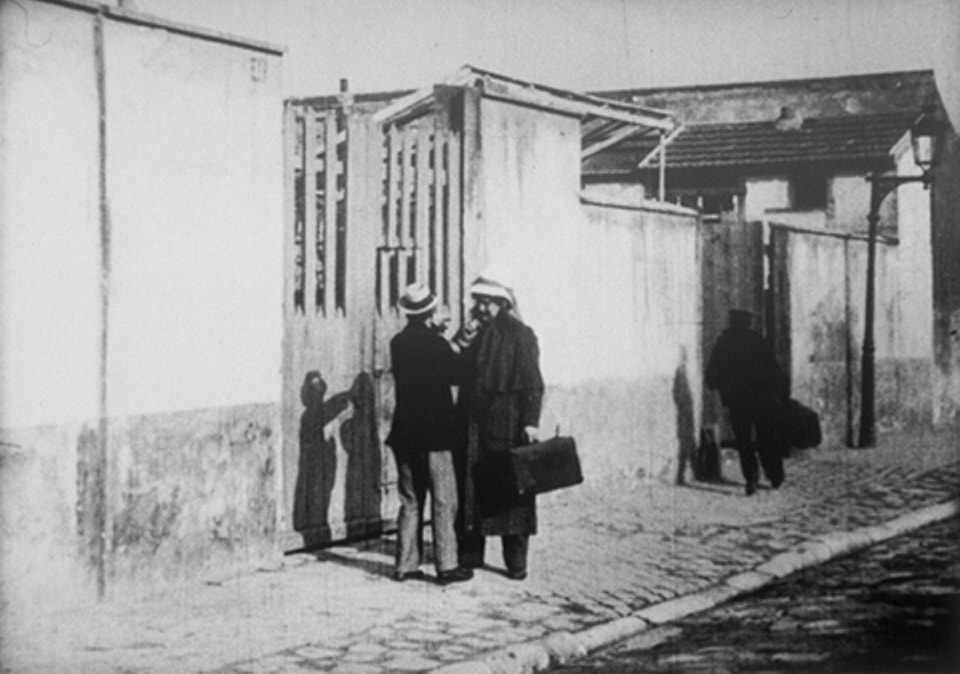

One of the actors in Le Charpentier maladroit has been identified with an actor in Voyageur et voleurs, wearing the same outfit. The implication would be, then, that the latter film was shot on a street near where Hatot and Breteau were based. This postcard (right) shows the Impasse de Montfaucon after it became incorporated into the Rue Edouard Pailleron; the pavement and streetlamp are points of similarity with Voyageur et voleurs but the buildings don't quite match.

|

|

The street number isn't legible in the photogram above but apparently it is 11, which rules out the Impasse de Montfaucon as location because no.11 there was a wine shop. There appears to be a number 11 on the shop that we see in the Hatot-Breteau film Les Deux Ivrognes, below, from which I conclude that this might be the widow Dapoigny's wine shop at 11 Impasse de Montfaucon: |

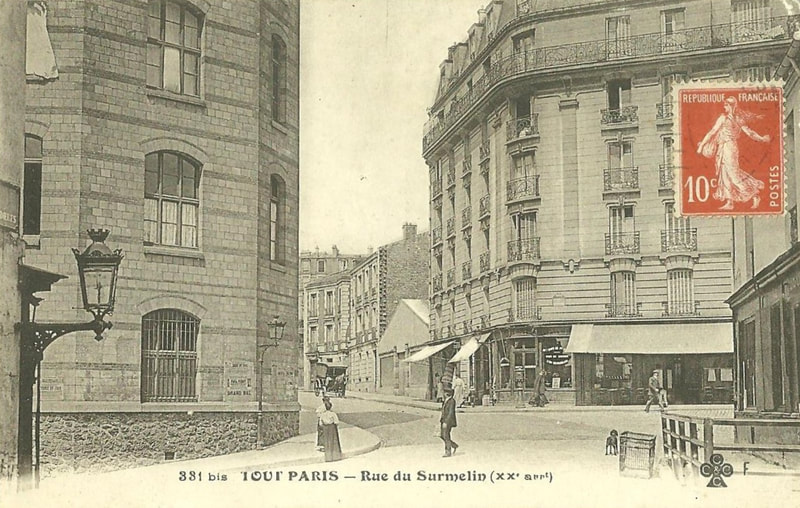

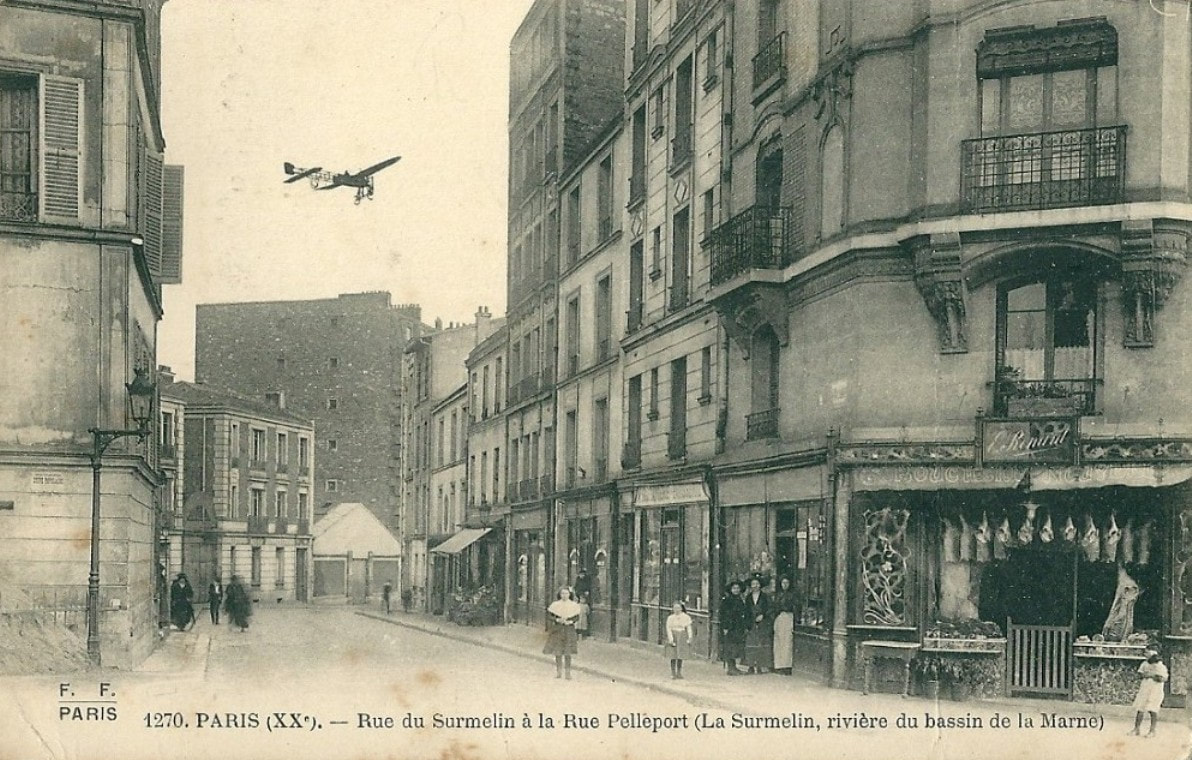

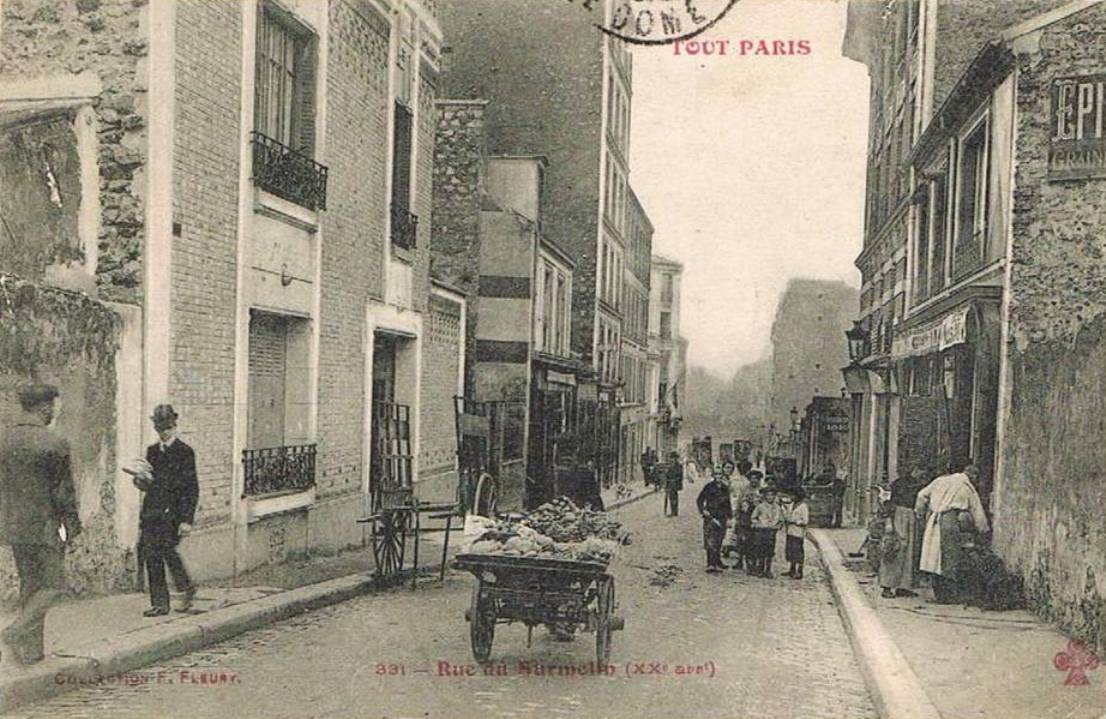

By 1898 Hatot and Breteau had moved from Belleville to Ménilmontant, having acquired a plot of land on the Rue du Surmelin. I haven't worked out where this terrain was on that street, which is quite long, with at the time quite a bit of available open space. Hatot says it was behind the Hôpital Tenon, but he doesn't say how far behind:

Here are views of the more built-up parts of the Rue du Surmelin:

|

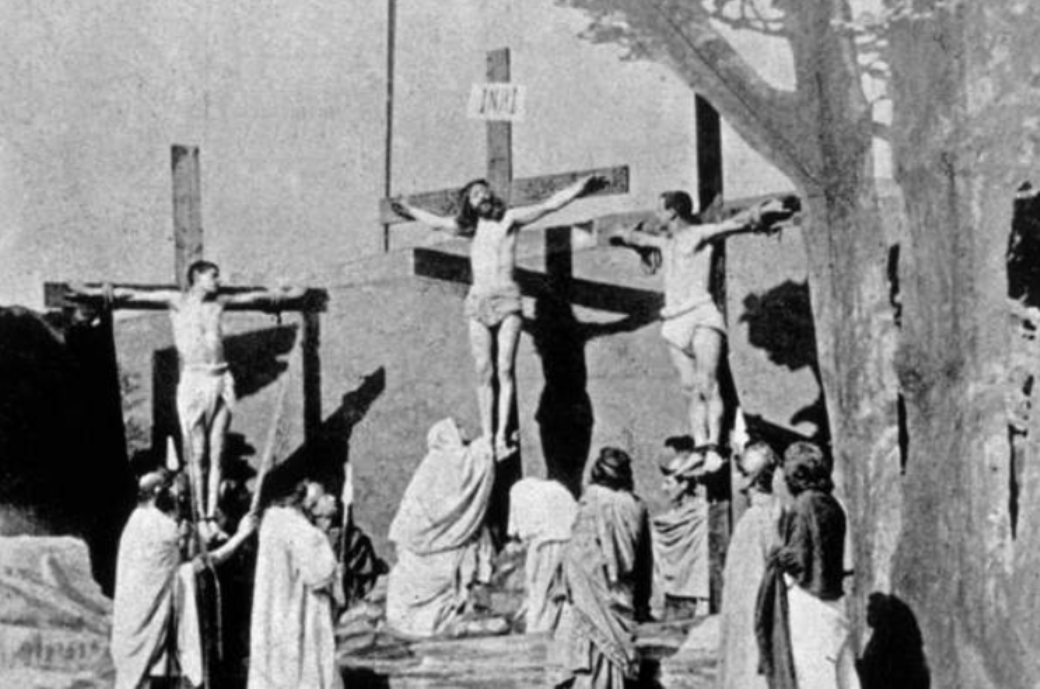

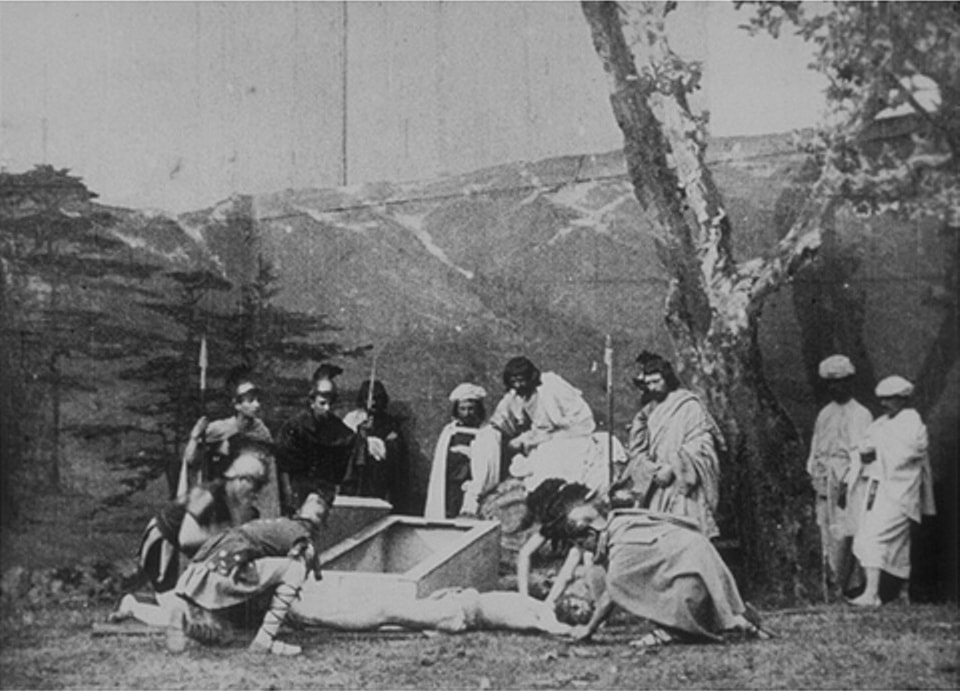

During the second interview in 1948, Hatot is watching some of his films with Langlois and Musidora, including the Christ-Passion made for Lumière. At the crucifixion scene Langlois asks 'are those Paris houses in the background?'. The image of the resurrection reproduced in Georges Sadoul's Histoire générale du cinéma (right), shows that there is a building beyond the wall, but doesn't show enough for identification. I haven't seen any other image from the Passion sharp enough to show anything beyond the wall. |

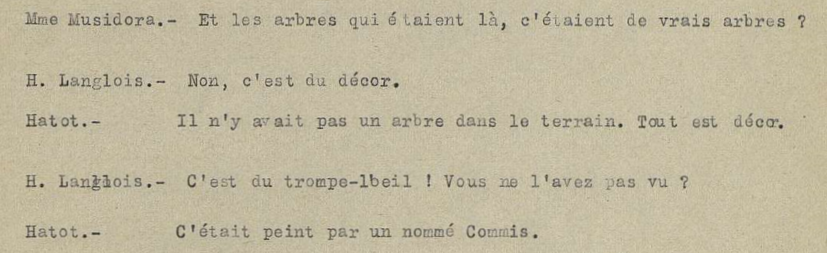

So the Passion film provides no clue as to where was Hatot's terrain on the Rue du Surmelin. Nor is anything visible beyond the wall in Combat sur la voie ferrée (below left), a film made at the same place, with the same trees - Musidora asked Hatot if they were real and he said 'no, it's all décor':

|

Normally I would say that the similarity of décor points to Combat sur la voie ferrée and the Lumière Passion being made at the same time, but these rather poor images of Breteau's Passion film for Gaumont, made some months later, appear to still show those fake trees (right), and the set representing the walls of Jerusalem in both films is the same (Lumière below left, Gaumont below right), so recurring décors do not necessarily indicate a chronological match. |

2/ décors

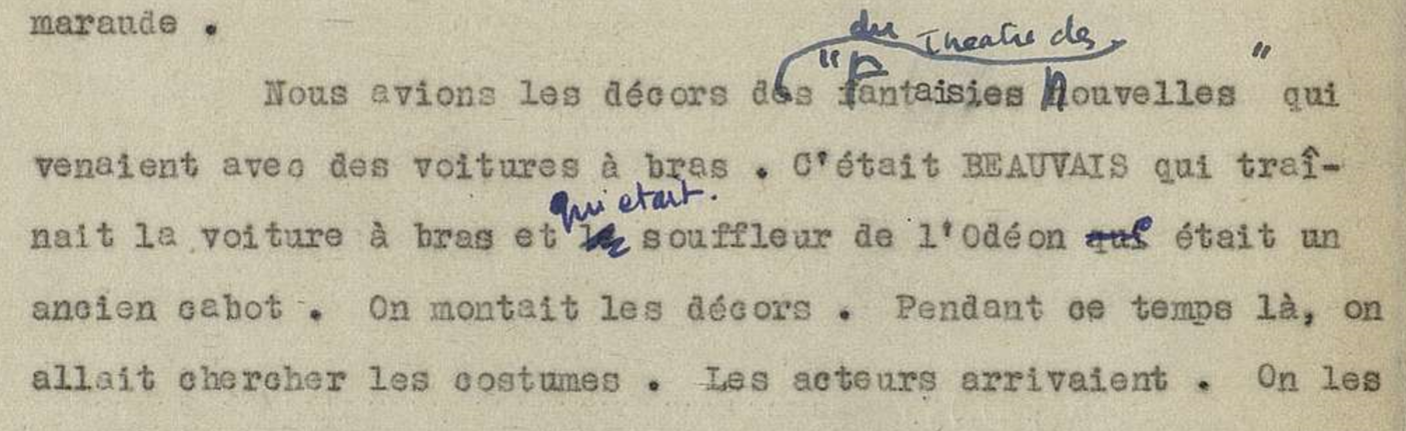

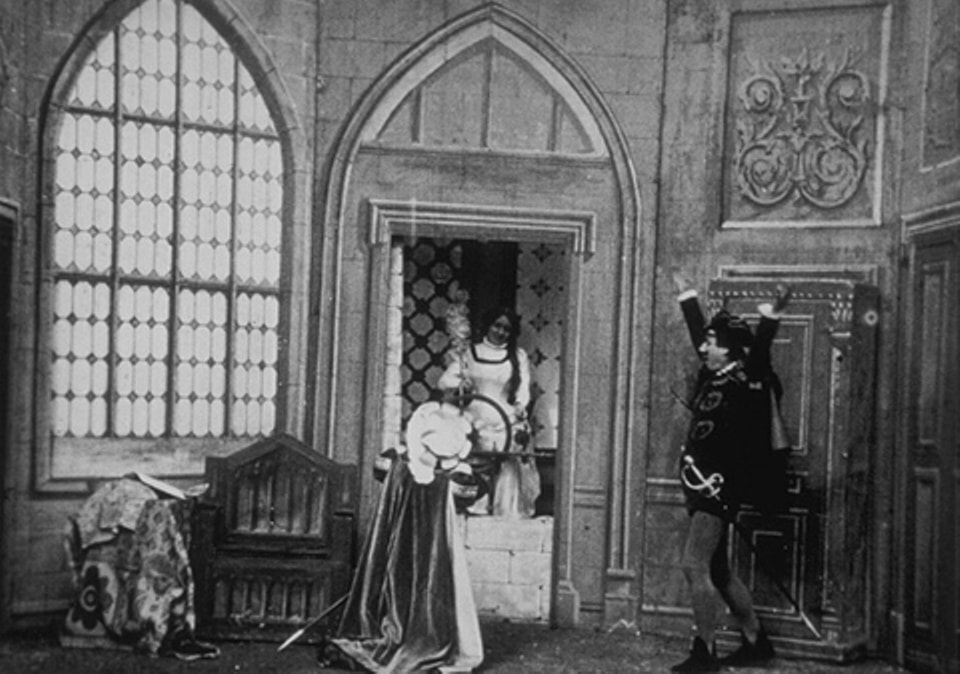

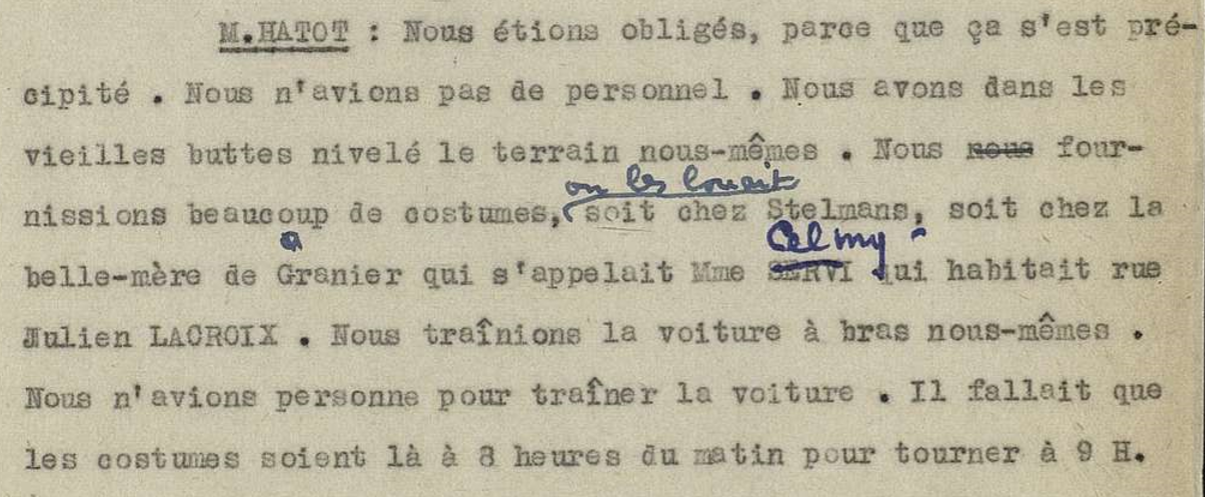

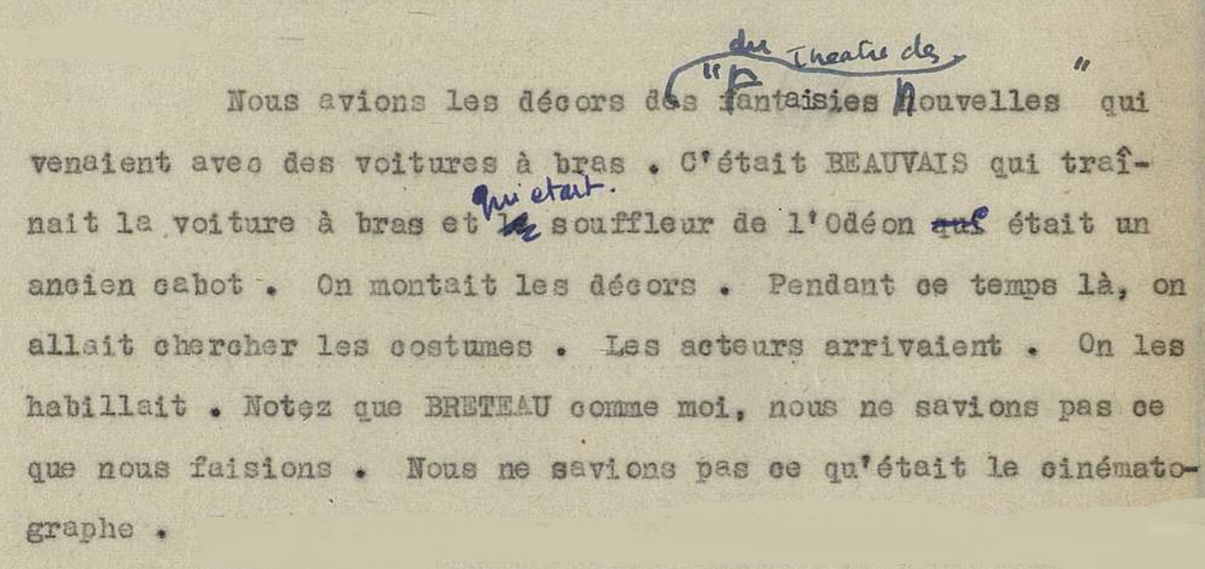

Most of the Hatot-Breteau films for Lumière use sets rather than real locations. These décors, says Hatot, were borrowed from a theatre, the Fantaisies Nouvelles on the Boulevard de Strasbourg:

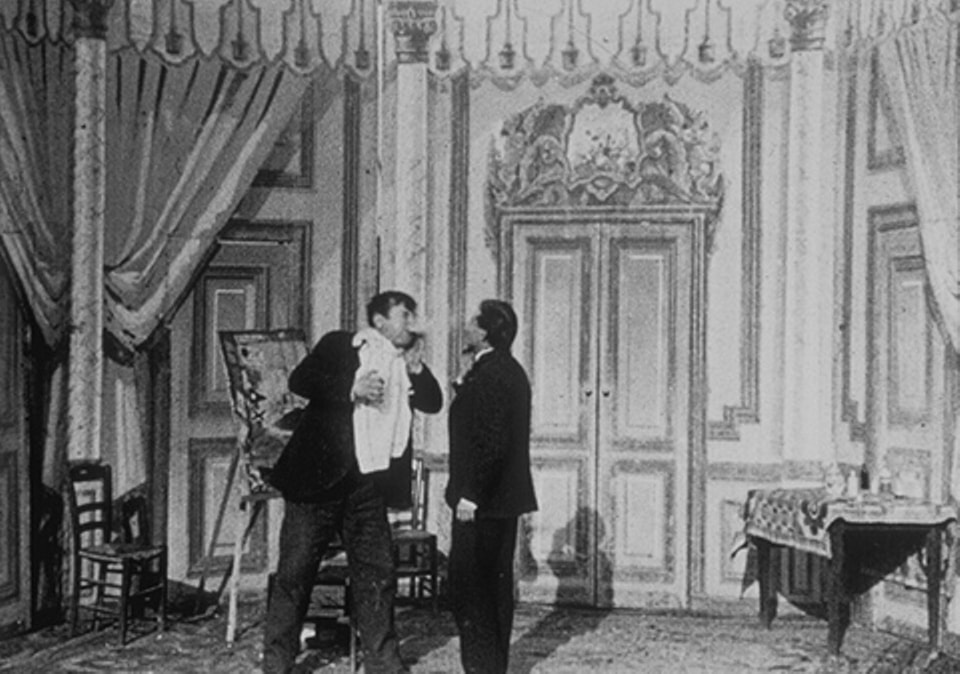

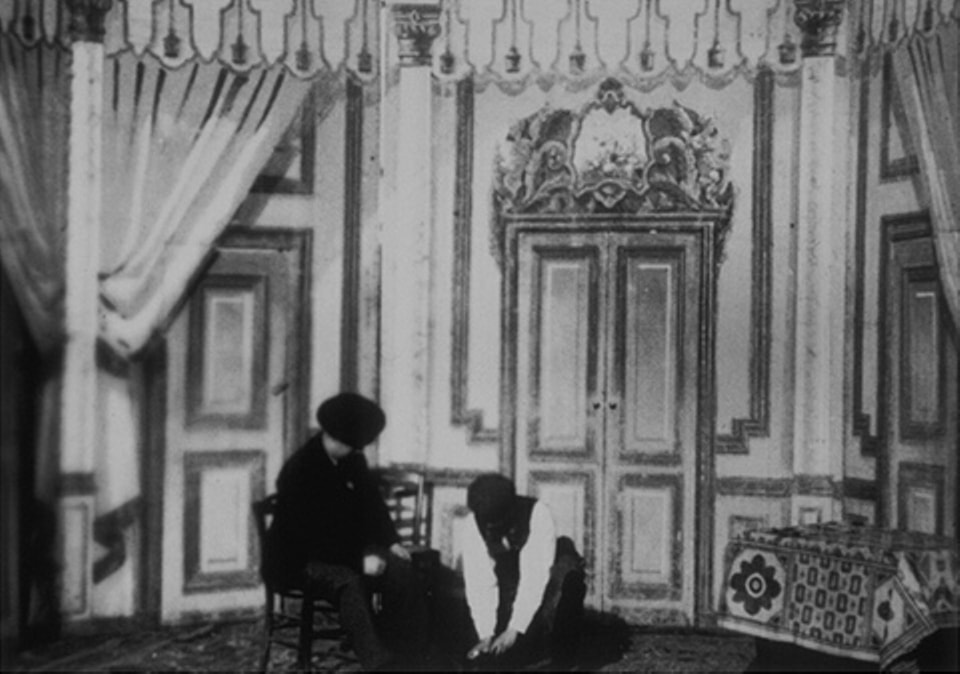

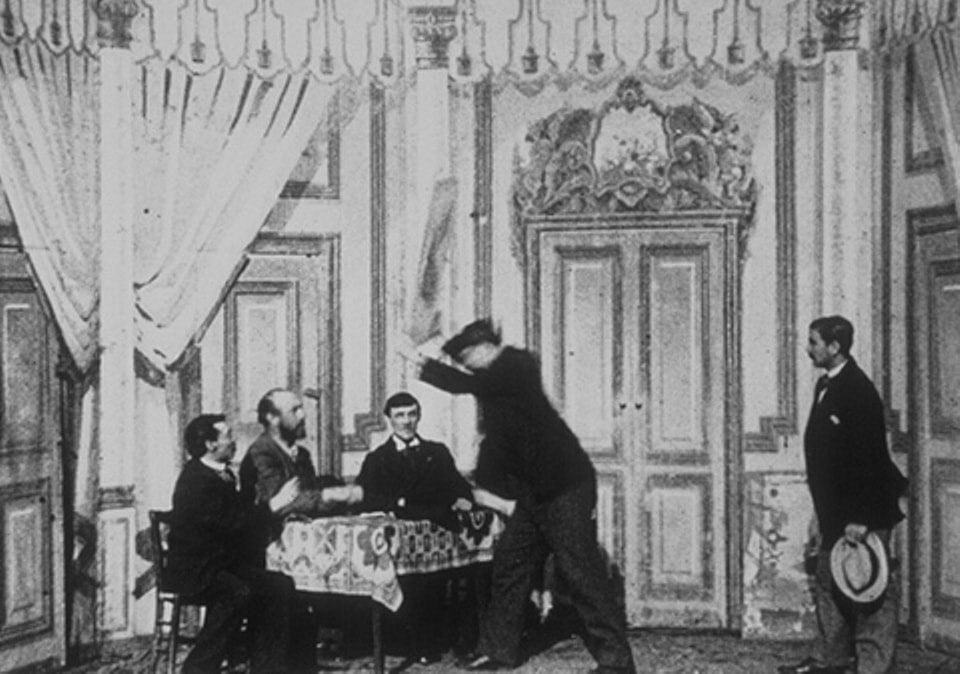

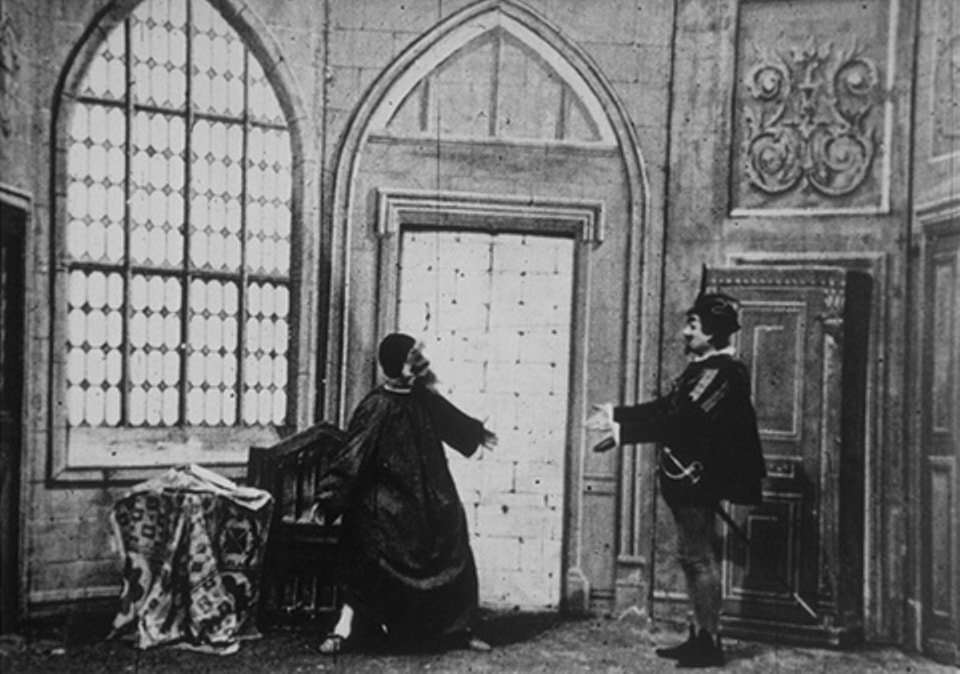

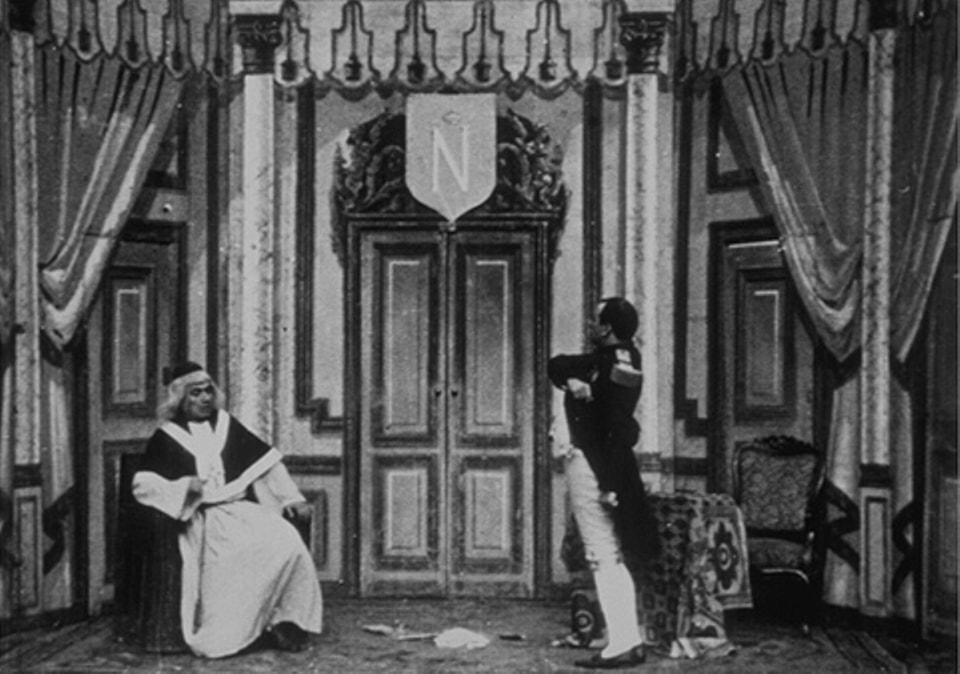

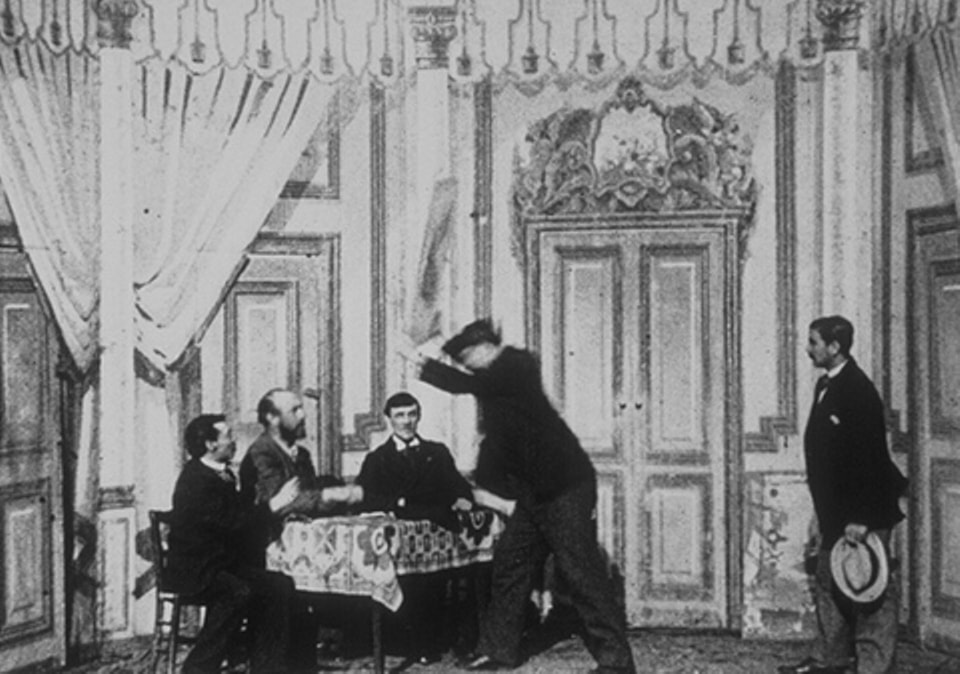

In several films the same décors recur, so we can see, for example, Napoleon signing the treaty of Campo-Formio in 1797 and then several years later arguing with Pope Pius VII in the same room, though they are supposed to be at Fontainebleau - the fittings have been slightly adjusted:

It is a little odd then to see three contemporary farces played out in this same room, one involving a dentist and his patient, another a cobbler and his customer, and the last an artist and the jury that has rejected his painting:

It is also odd to see in one film Napoleon chastising a sleeping sentry and then to find, in front of the same landscape, a Russian dancer performing his act:

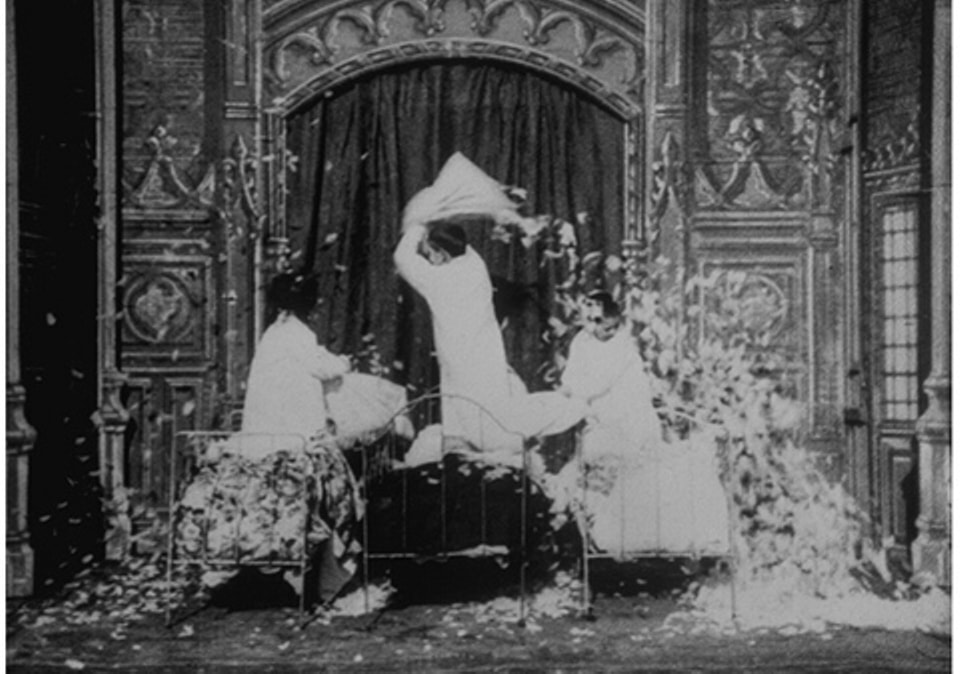

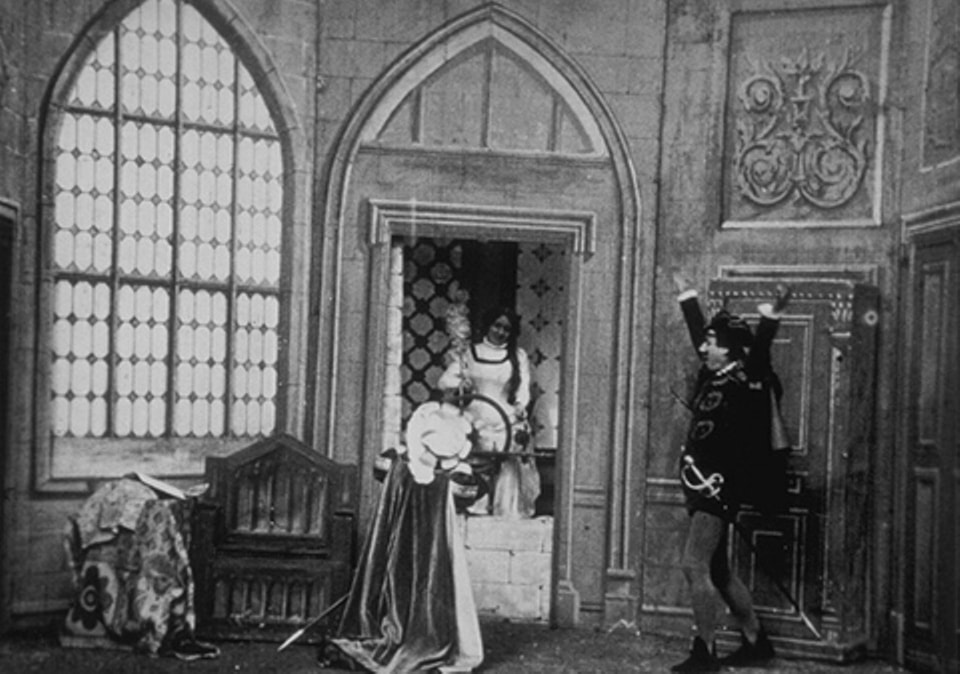

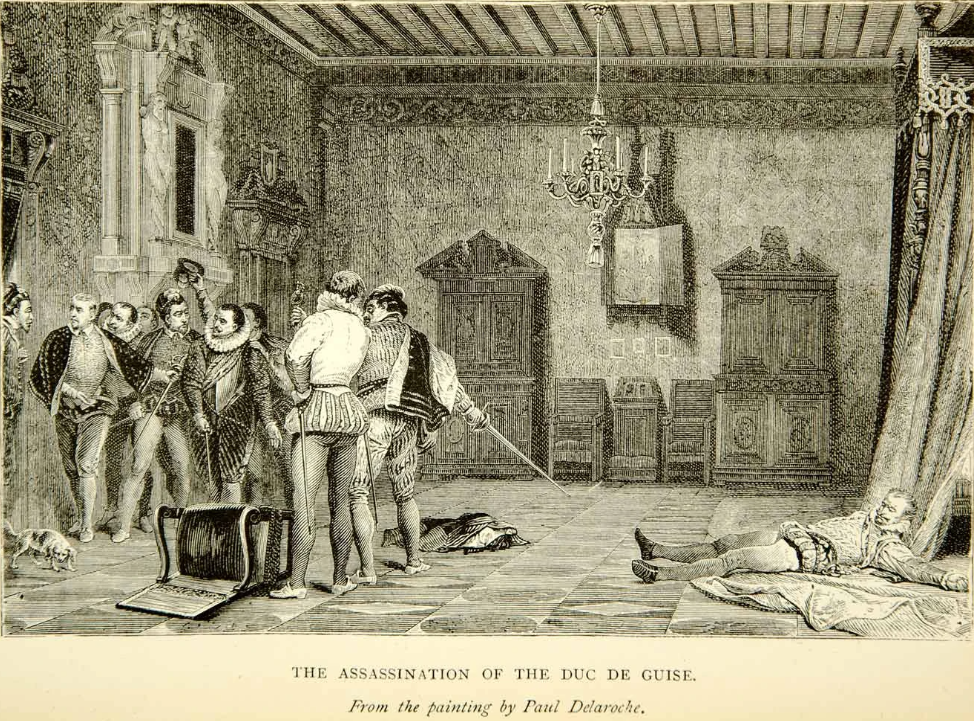

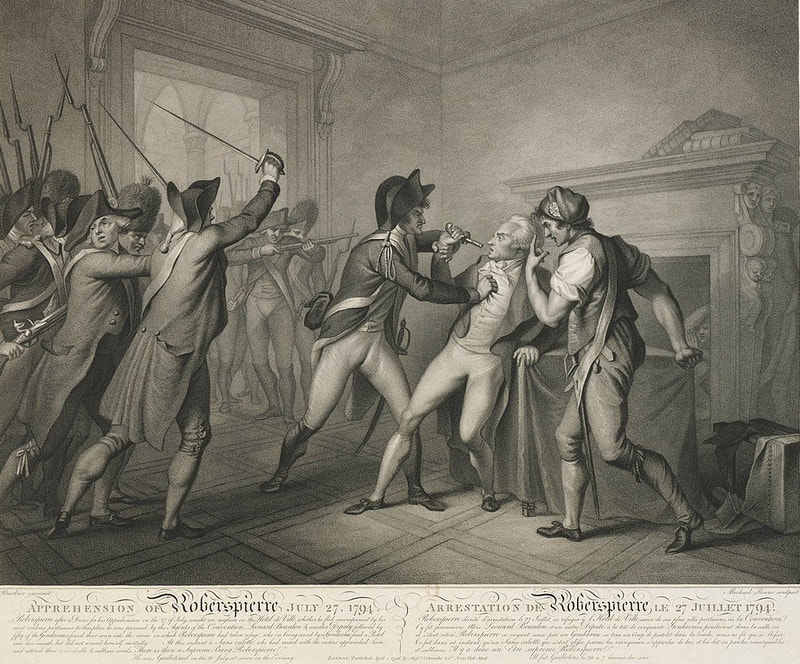

Odder still is it to see Bluebeard's castle as the setting for the assassination of the Duc de Guise in 1563 and the shooting of Robespierre in 1794, before three modern-day children arrive to have a pillow fight there:

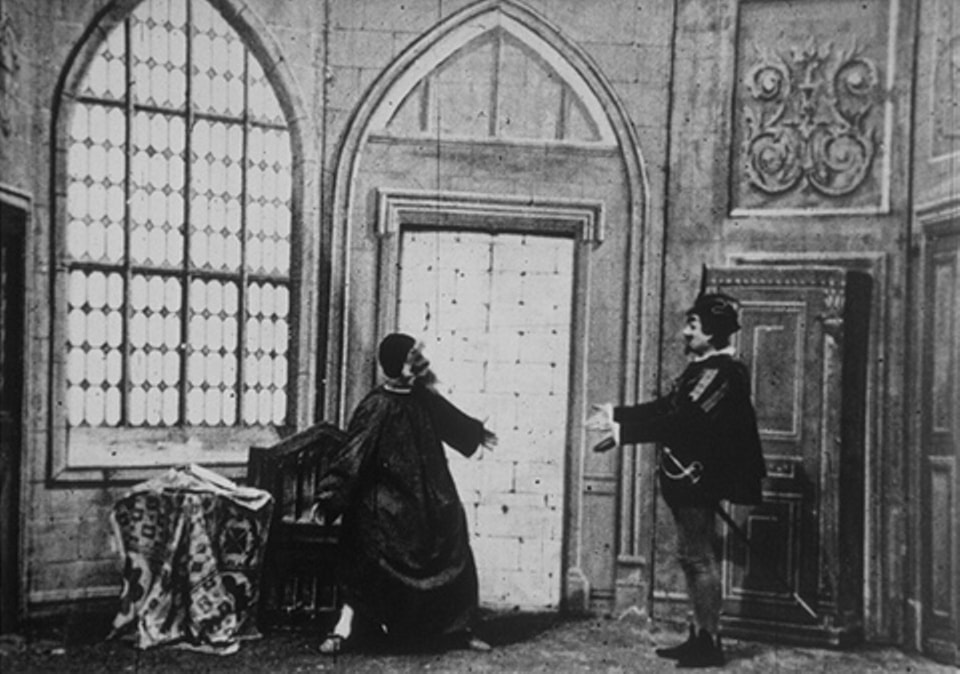

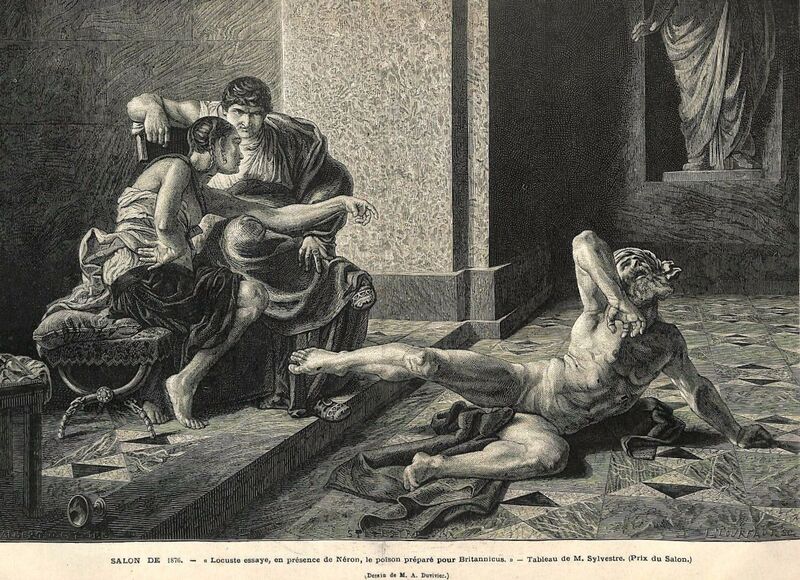

By contrast, seeing Charles the First preparing for his execution in the same room where Mephistopheles had visited Faust is not so sensational, likewise seeing Napoleon's general Kléber assassinated in Cairo in the same setting where almost 2000 years before in Rome Nero was testing poisons on slaves:

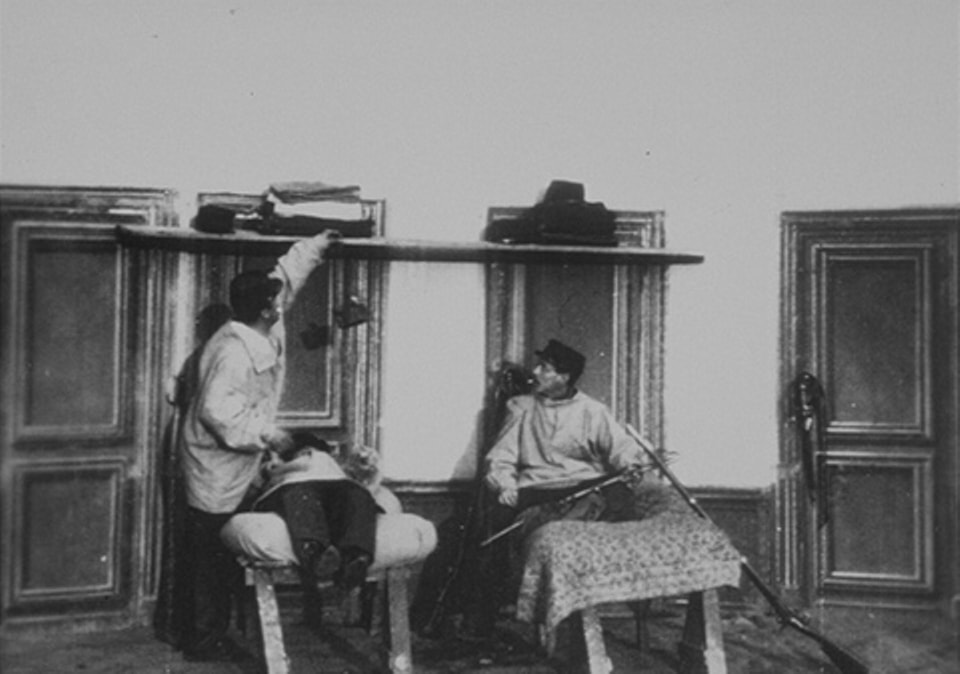

Hatot says that the décors were brought over in a handcart; they probably had to be returned quickly so we can assume that the films sharing décors were made at the same time. Most, as you can see above, are quite elaborate décors, though a plain set of bare walls and basic doors are sufficient backdrop to a farce in an army infirmary and to the tribulations of a concierge:

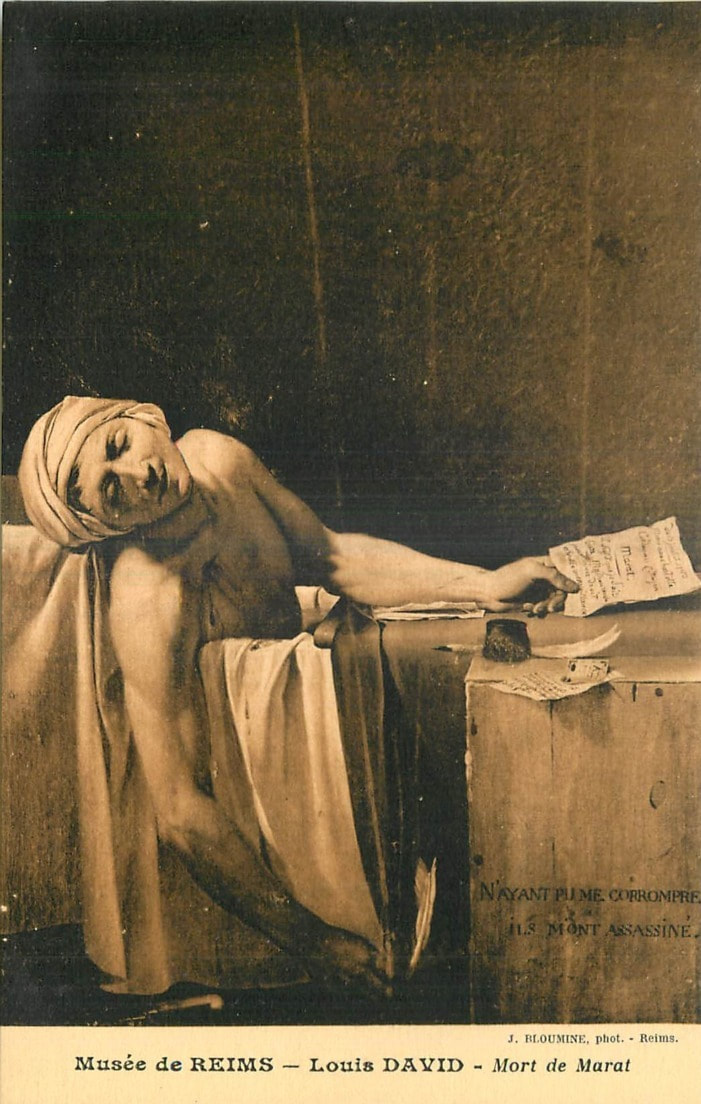

Basic props - a rifle, a sign saying 'concierge' - differentiate these spaces. The same backdrop is used for the death of Marat in 1793, but with a much more interesting prop - Marat is taking his bath in front of a map of France. That same map is also present at the signing of the Treaty of Campo-Formio:

I started this post wanting to fix the exterior locations of Hatot's Lumière films, then got distracted by the recurrent décors of those films, but these have just brought me back to what was the starting point of The Cine-Tourist website in 2011, an attempt to inventory the use of maps in films. I think that in La Signature du traité de Campo-Formio and La Mort de Marat, both 1897, we have the earliest appearances of maps in film.

3/ reading the décor

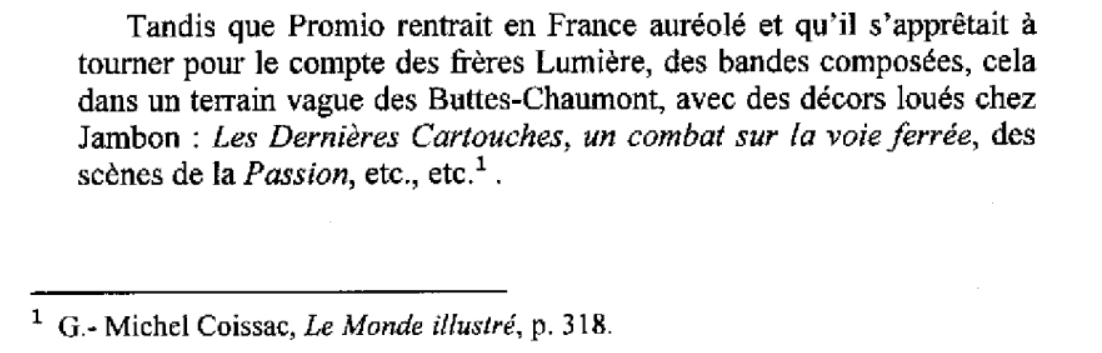

Finding these maps did seem like a good place to bring this post on exteriors to a close, but I have been troubled by the scenery along the route of the detour taken between those two topoi. More exactly I have been trying to understand how exactly Marcel Jambon came to be associated with Hatot's first films. The origin of the story appears to be film historian's G.-M. Coissac's 1925 article on Promio, quoted here in Jean-Claude Seguin's Alexandre Promio book:

In his Histoire du cinématographe (1925) Coissac had published extracts from Promio's memoirs, so I assume that it was in the unpublished part of his text that Promio said he made those films using décors hired from Jambon.

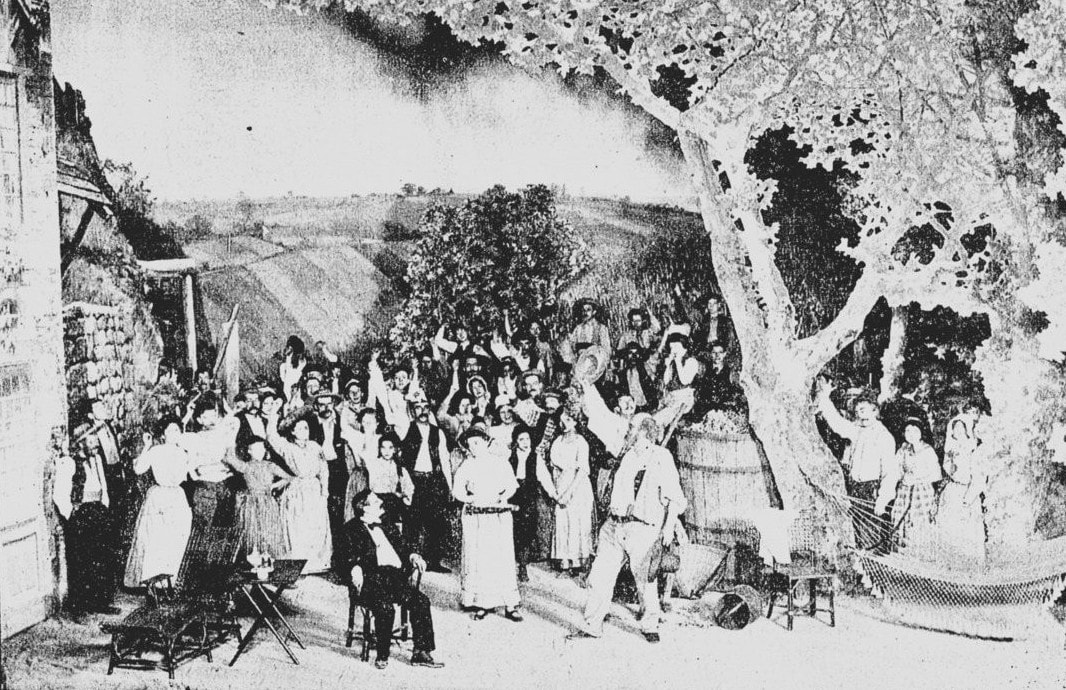

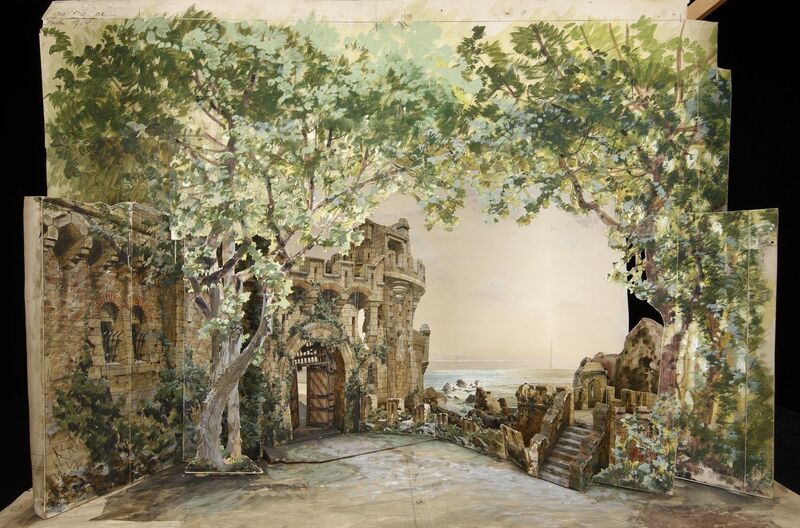

I don't dispute the possibility that on occasion Hatot and Breteau may have used a décor made by Jambon. Below we can see a tree that featured in Jambon's set for a production of Jules Mary's La Pocharde in February and March 1898, at the Théâtre de l'Ambigu-Comique, and then appeared in three of the tableaux in Hatot and Bréteau's Passion, filmed some time in April or May 1898:

I don't dispute the possibility that on occasion Hatot and Breteau may have used a décor made by Jambon. Below we can see a tree that featured in Jambon's set for a production of Jules Mary's La Pocharde in February and March 1898, at the Théâtre de l'Ambigu-Comique, and then appeared in three of the tableaux in Hatot and Bréteau's Passion, filmed some time in April or May 1898:

When La Pocharde closed on April 3rd, the tree either went back to Jambon's studio and soon after went to Breteau and Hatot's terrain on the Rue du Surmelin, or the tree went straight to the Rue du Surmelin from the Théâtre de l'Ambigu-Comique.

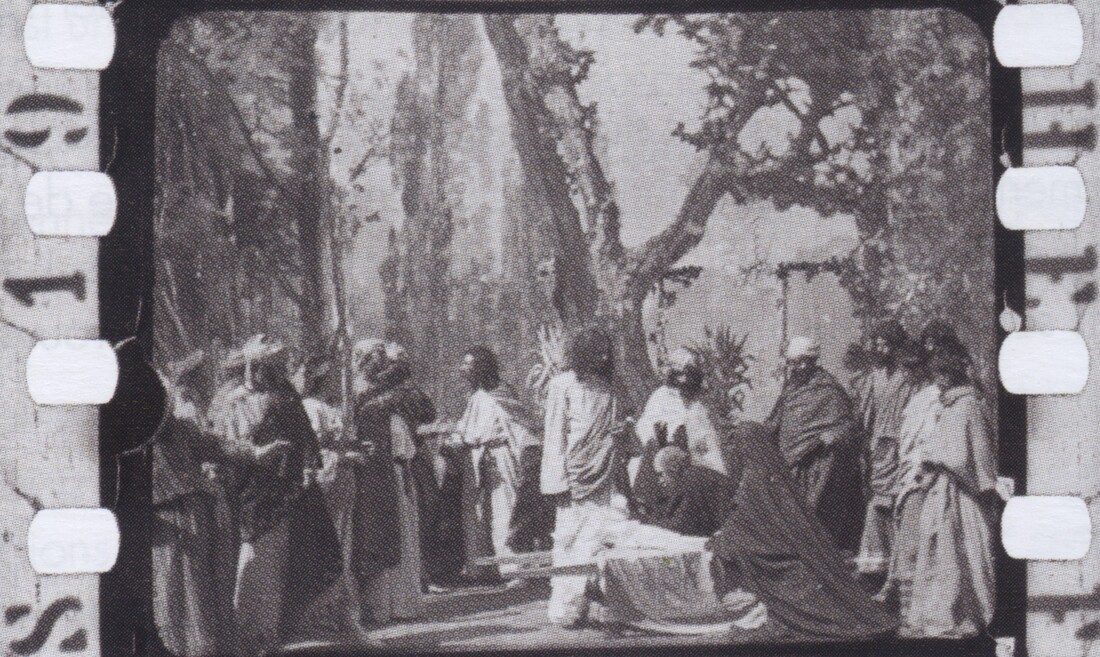

I suspect that the tree was never returned to Jambon, since when Breteau went to work for Pathé in 1898 and made a third Christ-Passion film for that company, he appears still to have had the tree:

I suspect that the tree was never returned to Jambon, since when Breteau went to work for Pathé in 1898 and made a third Christ-Passion film for that company, he appears still to have had the tree:

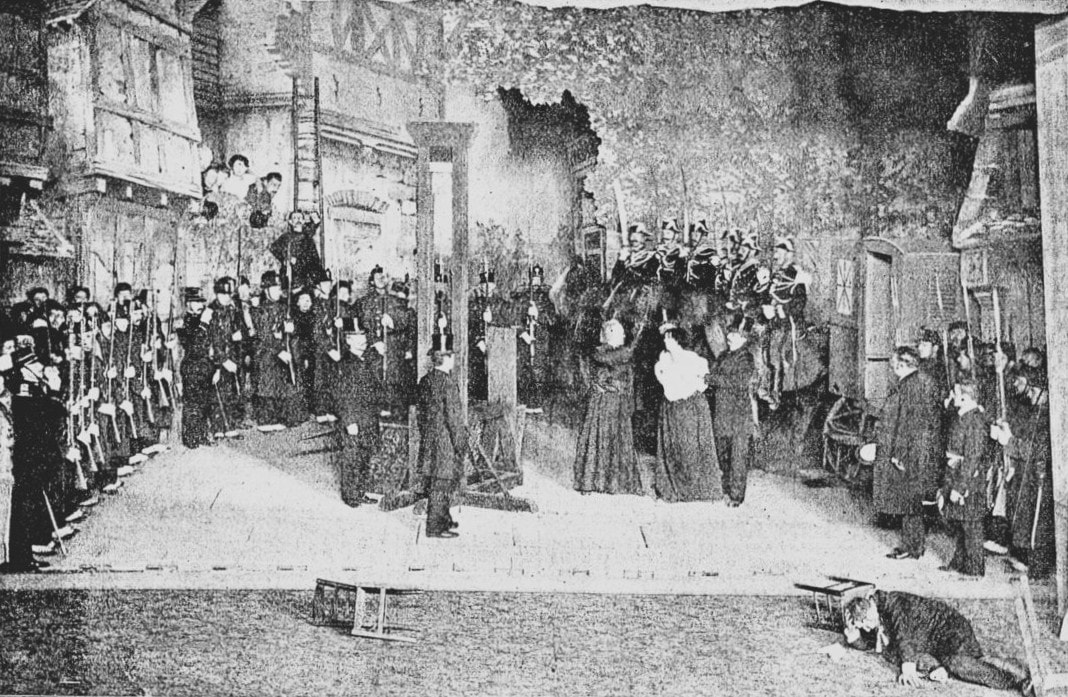

Another tableau from La Pocharde has elements that look like something in another Breteau-Hatot film from 1898, L'Exécution de Jeanne d'Arc:

The buildings on the left in each image are similar, but not the same, and I think the similarity is a coincidence, as is the fact that these are both execution scenes.

I have seen images of Jambon décors for about fifteen productions between 1895 and 1899, and the tree in La Pocharde is the only element in them that also appears in a Hatot-Breteau film. The received idea that Jambon designed sets for Lumière films as part of a Promio-led team is false. Jambon had much more important work to be getting on with than this, and if it so happened that in a film Hatot and Breteau used a piece of scenery originally made by Jambon's workshop for an unconnected stage production, this cannot be called designing for the cinema in the way we understand that now.

Moreover, in 1948 Hatot had told Musidora and Langlois who designed the sets for the films he made with Breteau:

'It was was painted by someone called Commis', says Hatot. I only recently realised that 'Commis' must be a mistranscription of Comy. Emile Comy was the director of the Théâtre des Fantaisies Nouvelles, from which Hatot and Breteau obtained their décors. I was perplexed, however, at the idea that this eminent and highly-experienced theatre director would himself be painting the décors for his productions. The answer came when I discovered that he had a son, Pierre, a painter who specialised in theatre décors. He worked with his father at the Eden-Théâtre in Brussels in the 1880s, and for several Paris theatres in the 1890s, including the Fantaisies Nouvelles. It is clearly Pierre Comy who should be credited with the décors of the Hatot-Breteau films made for Lumière in 1897 and 1898. Hatot and Breteau also made films for Gaumont in 1898; a letter from Léon Gaumont dated June 4th 1898 refers to a contract between them and is addressed to Hatot, Breteau and Comy, i.e. George, Gaston and Pierre.

As we have seen above, the background décors used by Hatot and Breteau appear across several films; the same is true of certain props and furnishings. I have already mentioned the map in the Marat and Campo-Formio films. A distinctive table-cloth reappears in six films, and is not always associated with the same background décor. Here it is in Chez le cordonnier, La Mort de Robespierre (showing its reverse side) and one of the Faust films:

The armchair in the Faust film above also appears in Scène chez l'antiquaire, Barbebleue and La Mort de Charles premier:

The windows in Scène chez l'antiquaire also appear in Les Dernières Cartouches and in the Marat and Robespierre scenes:

And the dais on which is placed Nero's throne serves also for the throne of Pontius Pilate:

Where films are made in or around a workplace or studio, as with Méliès and later Gaumont and Pathé, the recurrence of sets, props and costumes is normal. These companies had repositories for storing such objects, or workshops for making them. The circumstances in which Hatot and Breteau made their first films look more haphazard, at least as Hatot describes them, with sets and costumes collected on the day itself from suppliers:

Stelmans was near the Place de la République, Madame Selmy was more local:

I haven't noticed many recurring costumes, but it does seem odd, in these circumstances, that the same sets and objects recur. One explanation, as I have suggested, would be that the films with the same sets were made on the same day. But the objects that appear in front of different sets suggest that there was at least a small space of some sort in which these things were stored. It wouldn't surprise me if there were also some basic re-usable sets in that store room, at least by the time Hatot and Breteau had shifted production to the Rue du Surmelin.

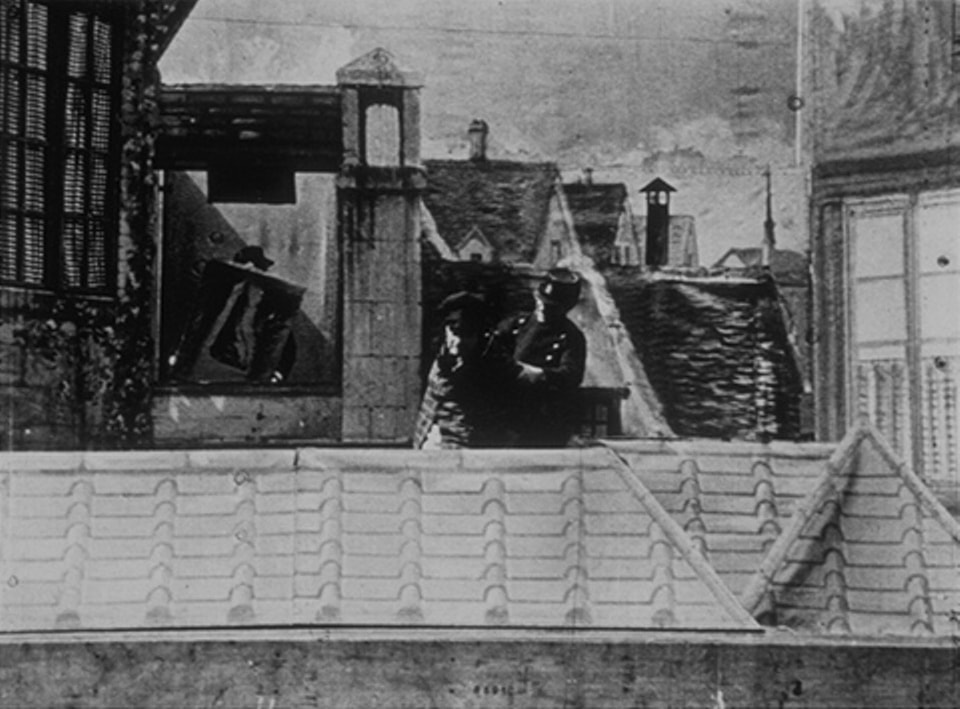

The best known example of a re-used set is the rooftop seen in two different films, one made for Lumière and the other for Gaumont. By this point, the story goes, Breteau was largely working on his own, as Hatot was doing his military service, and Breteau was remaking for Gaumont several films that had already been made for Lumière. Here, in Poursuite sur les toits (Lumière) and Les Cambrioleurs (Gaumont), is the same backdrop and set, with modified foreground:

One explanation given of this coincidence is that the set was bought by the Gaumont company from the Lumière company (McMahan, p.27), but this doesn't seem feasible since the Lumière filmmakers - Hatot and Breteau - were borrowing their sets from a theatre, so the set wasn't theirs to sell.

Another explanation offered (by Aubert and Seguin) is that the coincidence is unsurprising since Marcel Jambon was the set designer on the Lumière film and Jambon 'also worked with Alice Guy'. This is based on the erroneous assumption that Jambon was the supplier of all of the sets used by Hatot and Breteau, when all we can say for certain is that he supplied one tree. It is true that Guy did work with Jambon, but that was five or so years later, and anyway the connection only seems pertinent if we think Guy made the Gaumont film Les Cambrioleurs, but she did not.

Another explanation offered (by Aubert and Seguin) is that the coincidence is unsurprising since Marcel Jambon was the set designer on the Lumière film and Jambon 'also worked with Alice Guy'. This is based on the erroneous assumption that Jambon was the supplier of all of the sets used by Hatot and Breteau, when all we can say for certain is that he supplied one tree. It is true that Guy did work with Jambon, but that was five or so years later, and anyway the connection only seems pertinent if we think Guy made the Gaumont film Les Cambrioleurs, but she did not.

In his offensively titled lecture 'Alice Guy a-t-elle existé?', Maurice Gianati established that this and several other Gaumont films were made by Breteau - it is he who appears at the window, disguised as a woman - claiming that about forty films were made by Breteau and Hatot for Gaumont, mostly reworking films made for Lumière.

One of these remakes is the 1898 film called Les Métamorphoses de Satan in the 1900 Gaumont catalogue. (In the Gaumont compilation of her films it is attributed to Alice Guy, renamed Faust et Méphistophélès and re-dated 1903.)

One of these remakes is the 1898 film called Les Métamorphoses de Satan in the 1900 Gaumont catalogue. (In the Gaumont compilation of her films it is attributed to Alice Guy, renamed Faust et Méphistophélès and re-dated 1903.)

Les Métamorphoses de Satan is a fusion of the two Faust films Breteau and Hatot made for Lumière in 1897, re-using the décor (seen also in La Mort de Charles premier), as well as Satan's costume, though the chair and the table-cloth do not return:

|

Another difference is that the Gaumont film is played out on what looks like a raised concrete or wooden floor, the same that was the used for the Lumière film Poursuite sur les toits, showing that they were both made in the same space, no doubt at the Rue du Surmelin. The effect of that stage is to raise the performers towards the middle of the frame and to cut off the top of the décor that had in the earlier films fitted the frame perfectly.

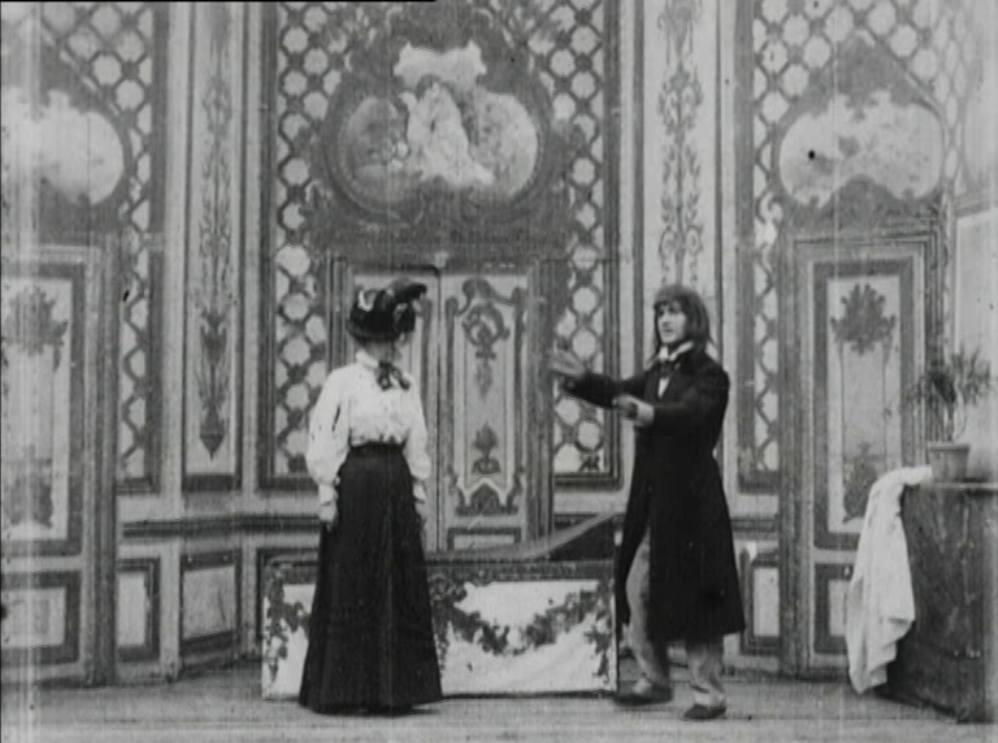

A further striking difference is what we see through the doorway in which Marguerite appears. Behind her in the Lumière film are decorative patterns on the wall, somewhat like wallpaper samples. Behind her in the Gaumont film is a picturesque landscape, with some sort of vegetation in the mid-ground and a cloudy sky beyond: |

The vegetation in that landscape is familiar, having appeared already in the Lumière films Néron essayant des poisons sur des esclaves and L'Assassinat de Kleber:

And it will appear again in the 1898 Gaumont film L'Aveugle fin de siècle:

|

If recurrent décor-use is a sign of authorship then L'Aveugle fin de siècle is a film we must attribute to the Breteau-Hatot team. Likewise for Quatre jours de clou (right), in which, despite the poor quality image, we can just about recognise the décor from the above. And we must, then, also attribute to them this Lumière film, because in it can be seen a part of the foreground décor used in L'Aveugle fin de siècle: |

The question is, though, can we use recurrent décor-use to say that a set of films are by the same person or persons. Once a studio is fully functioning we cannot, since the studio will have a repository of décors at the disposition of its filmmakers and the use of any particular décor won't be determinant, though recurring décor can, in those circumstances, tell us that a film is from one studio rather than another.

In the case of Breteau and Hatot, working for companies without a fully operative practice of producing and maintaining their own décors, reliant then on obtaining décors from external sources such as theatres, I would say that the presence in one film of a piece of décor used in another film is evidence that both films were made by the same people.

At this point a Jambon-type story might be invoked, according to which different filmmakers at different companies are acquiring décor from the same theatrical source. I don't believe this story (I call it le canard jambon) because there is little evidence for it and quite some evidence against it.

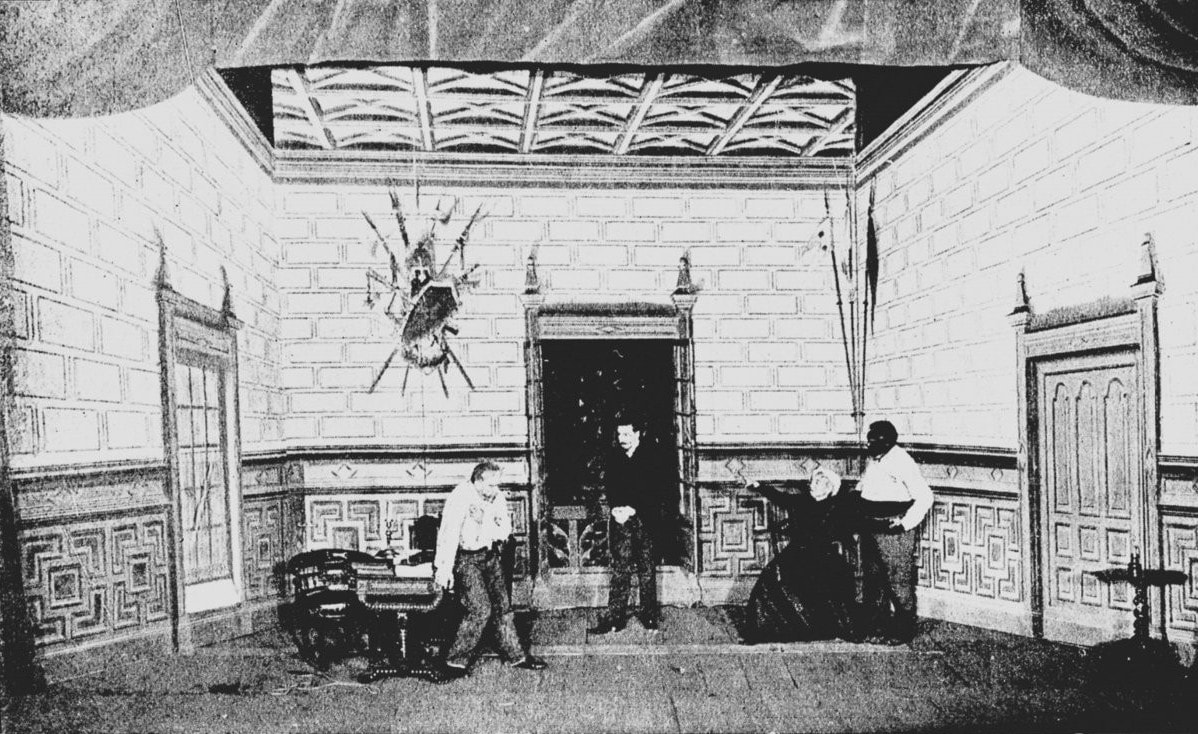

I had been tempted to argue that the sets we see in the Hatot-Breteau films are not of the quality evident in the stage work of Jambon, but to be fair there are some illustrations of the latter that show sets as basic as those in the films. For example, the wall at the back of this set by Jambon for Mamz'elle Bon-Coeur (1899, Ambigu-Comique) could easily be the wall in front of which the Hatot-Breteau Last Supper is eaten:

In the case of Breteau and Hatot, working for companies without a fully operative practice of producing and maintaining their own décors, reliant then on obtaining décors from external sources such as theatres, I would say that the presence in one film of a piece of décor used in another film is evidence that both films were made by the same people.

At this point a Jambon-type story might be invoked, according to which different filmmakers at different companies are acquiring décor from the same theatrical source. I don't believe this story (I call it le canard jambon) because there is little evidence for it and quite some evidence against it.

I had been tempted to argue that the sets we see in the Hatot-Breteau films are not of the quality evident in the stage work of Jambon, but to be fair there are some illustrations of the latter that show sets as basic as those in the films. For example, the wall at the back of this set by Jambon for Mamz'elle Bon-Coeur (1899, Ambigu-Comique) could easily be the wall in front of which the Hatot-Breteau Last Supper is eaten:

I have found no images of Pierre Comy's theatre designs, but I suspect that they wouldn't match the general standard of Jambon's work.

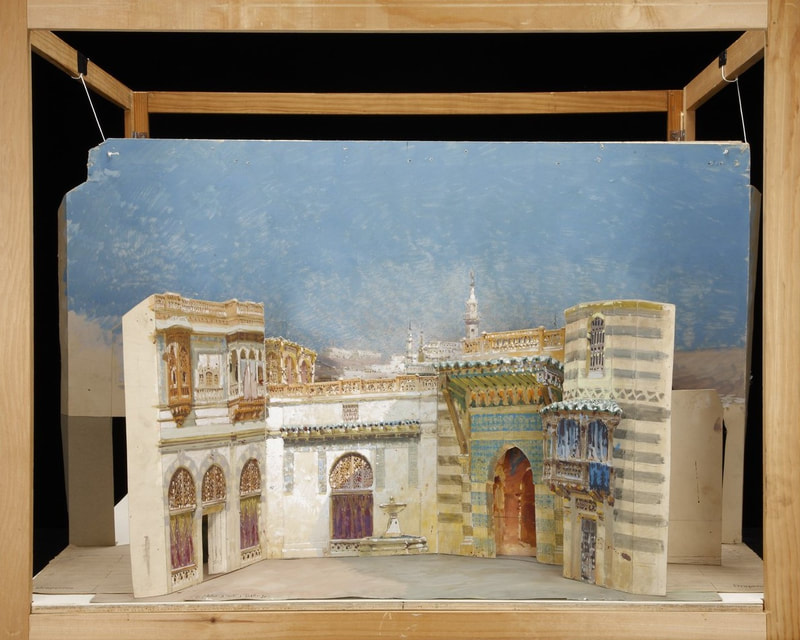

Here, for comparison with the Comy sets used in the Hatot-Breteau films, are a few of Jambon's designs for the theatre, viewed on Gallica. The comparison is not altogether fair, of course. These are, as Mariann Lewinsky Sträuli has pointed out to me, aquarelle sketches of planned stage sets with the sophisticated look and glowing colours of that genre, making quite a different visual impact from what the realised sets would have looked like :

Jambon did produce sophisticated designs for the cinema, but that was later, when the cinema could afford to pay for work of such quality. Alice Guy tells of commissioning ten backdrops from Jambon for a set of phono-scènes to be recorded with Caruso, only for the singer to withdraw at the last minute. Guy says she made use of Jambon's services on other occasions (though not for her Life of Christ, designed by Henri Menessier).

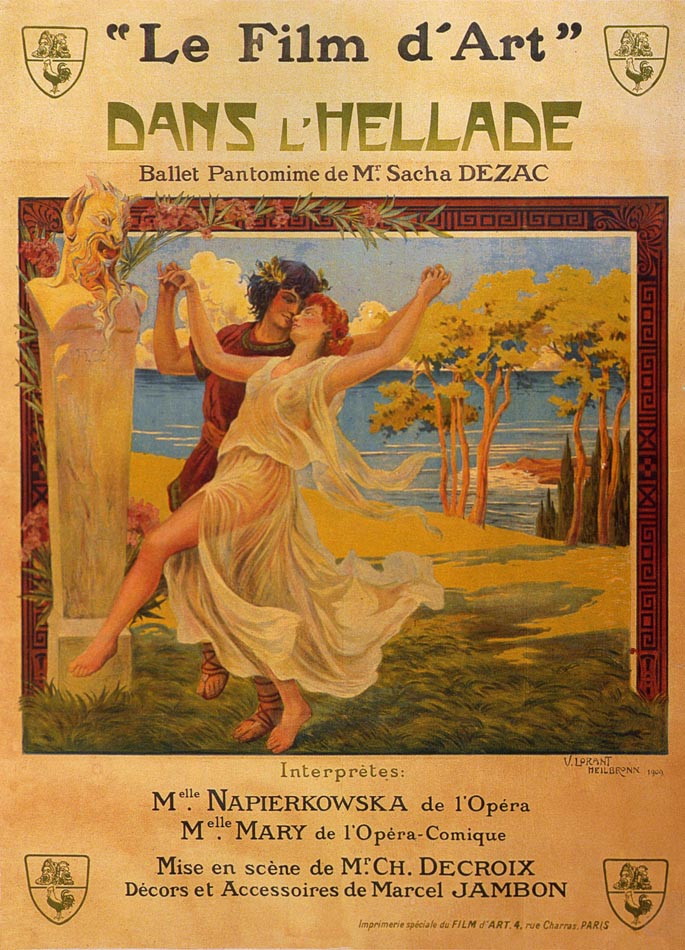

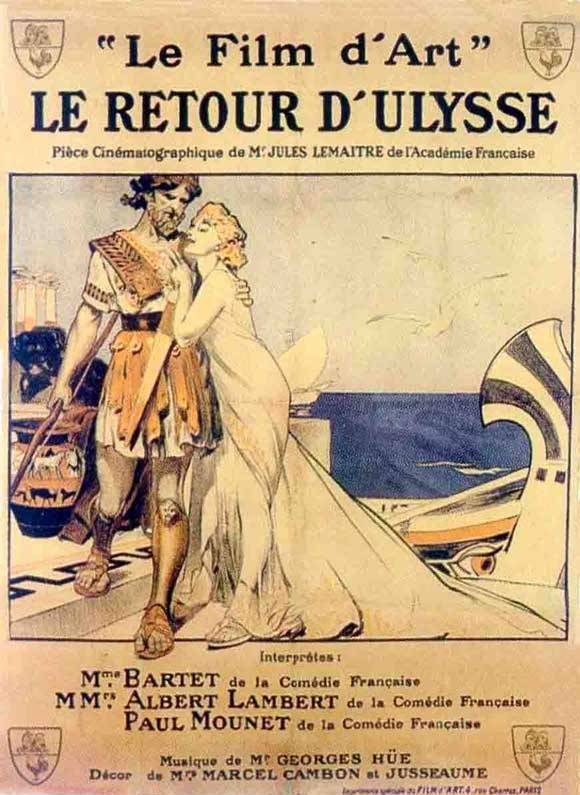

|

From these posters we can see that Jambon was involved in the rise of the 'Film d'Art'.

Below are stills from four of Pathé's 'Film d'Art' productions, dated November 1908, February 1909, March 1909 and January 1910, all supposed to have been designed by Jambon. Some of these commissions were probably completed by his partner Alexandre Bailly, since Marcel Jambon died in September 1908. The poster for Le Retour d'Ulysse credits Lucien Jusseaume alongside Marcel Cambon (sic). |

4/ auteurs?

Seguin's book on Alexandre Promio seeks to promote Lumière's cameraman, 'cet opérateur hors du commun', as some sort of auteur. Central to this reading is the moment when, in 1897, Promio took to filming reconstructions of historical events, mostly mediated by well-known paintings. The relevant films discussed by Seguin are Néron essayant des poisons sur ses esclaves, L'Assassinat du duc de Guise, La Mort de Charles premier, La Mort de Marat, La Mort de Robespierre, La Signature du traité de Campo-Formio, L'Assassinat de Kléber, L'Entrevue de Napoléon et du Pape, Les Dernières Cartouches and Combat sur la voie ferrée. In this context he also discusses the two Faust films and the Passion of Christ. These are all films made by Breteau and Hatot.

Seguin usefully situates these films in a pictorial context, both painterly and cinematic, but his efforts are all directed at promoting Promio:

|

|

In September a reorientation brings Promio to Paris, where he will make composed films ['réaliser des bandes "composées"'] i.e. the first historical views. (p.112)

With these composed films [...] we pass from individual labour to collective enterprise. Hence for all of the views filmed at this moment, in Paris, at least three men - not counting the actors - were working together: the operator ['preneur de vues'], the director ['metteur en scène'] and the designer ['décorateur']. The first was, obviously, Alexandre Promio, the second was Georges Hatot, the last was Marcel Jambon. To these names should be added that of the actor Bretteau [sic], whose rôle was, apparently, not negligeable. (pp.112-13) Consultation of the Lumière catalogue reveals a certain number of views with a chiefly historical theme, even if treated in terms of pictorial representation. Numbers 290 to 302 must be attributed to Alexandre Promio and his team ['équipe de tournage']. We can consider that he was the author of other views, but prudence is called for, even if in the present case it is quite probable that the task was allotted to a single filmmaker ['que l'on a demandé à un seul "cinéaste" de réaliser ces tournages']. [p.118] |

Seguin plays up Jambon's contribution, plays down that of Hatot, and says nothing of Breteau:

|

|

The rôle of Marcel Jambon was no doubt far from negligeable in the realisation of these 'historical views' [...], was probably essential, since he is part of a pictorial culture keen on heavily dramatised historical representation. [pp.116 & 118]

Unlike Marcel Jambon, Georges Hatot was then just a young man with only rudimentary knowledge of the scenographic art. It is highly probable that Alexandre Promio intervened directly in certain aspects of the staging. He was in any case the 'cinéaste' who composed these films. [p.117] |

Seguin identifies pictorial precedents for the Nero and Duc de Guise films:

For the five films related to the Revolutionary period or to Napoleon, Seguin suggests that the models not so specific but are, rather, part of a collective culture on which all image makers drew. Here are four of those films in vis-à-vis with print representations of the same scene:

For the Death of Marat there are well-known precedents in painting, and Seguin mentions both David and Hauer (below left and centre). At first it occurred to me that, because of the presence of a map in the Marat film, the 1860 painting by Baudry (below right) might be a model:

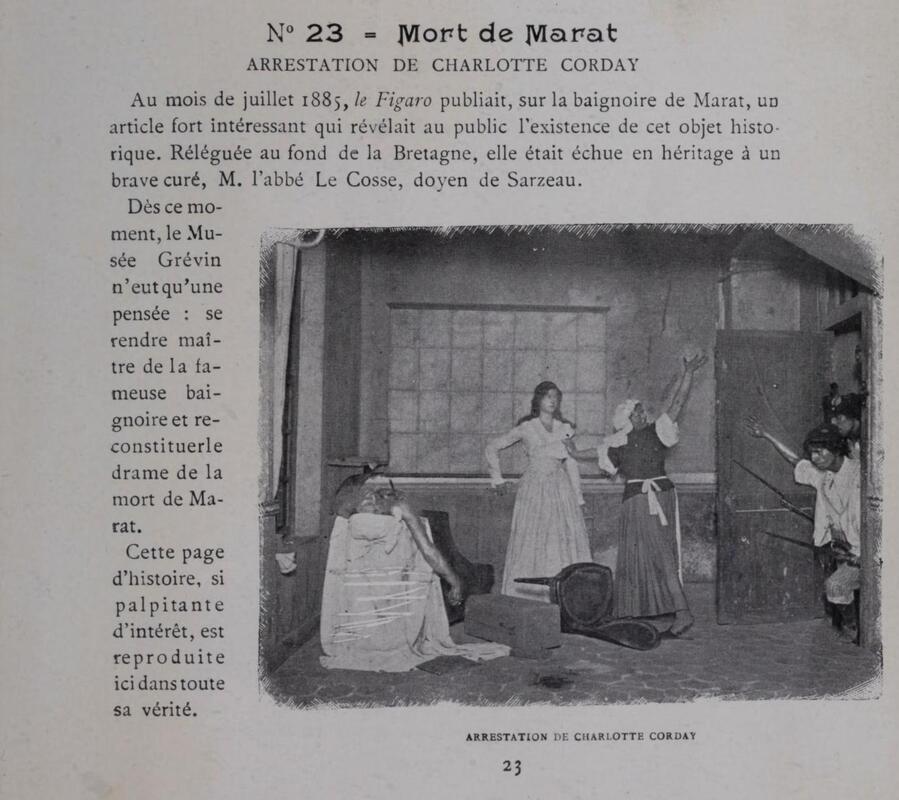

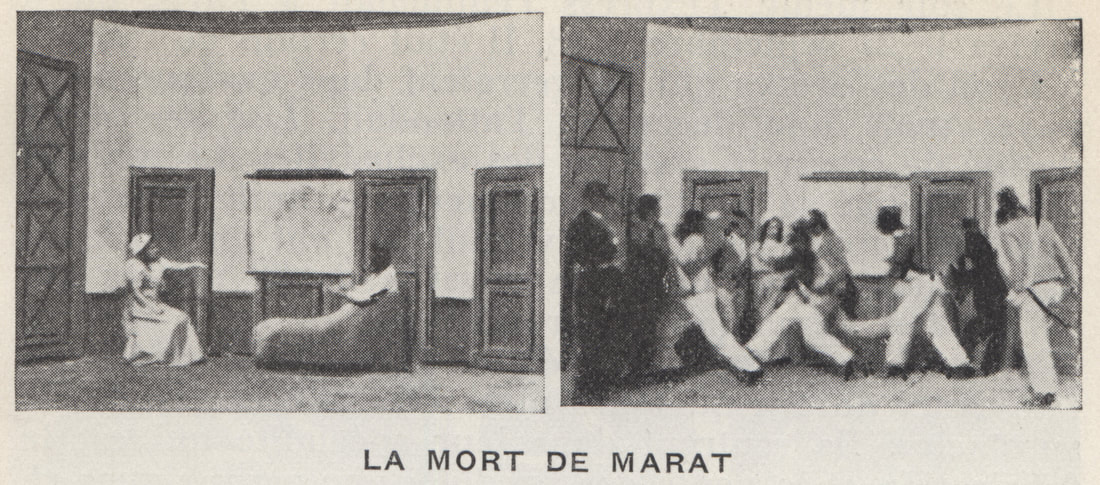

But I now think that this is based on a waxwork exhibit, not a painting:

|

The Musée Grévin's 'Death of Marat' exhibit opened in 1886. It featured the actual bathtub in which Marat died and several other authentic period objects, including a map of France from 1791. As well as replicating the map, the set of the Hatot-Breteau Mort de Marat matches the sparseness of the Musée Grevin staging. |

In 1947 Georges Sadoul had already suggested that some of these Lumière historical films might be inspired by 'stereoscopic views, tableaux vivants and waxwork museums'.

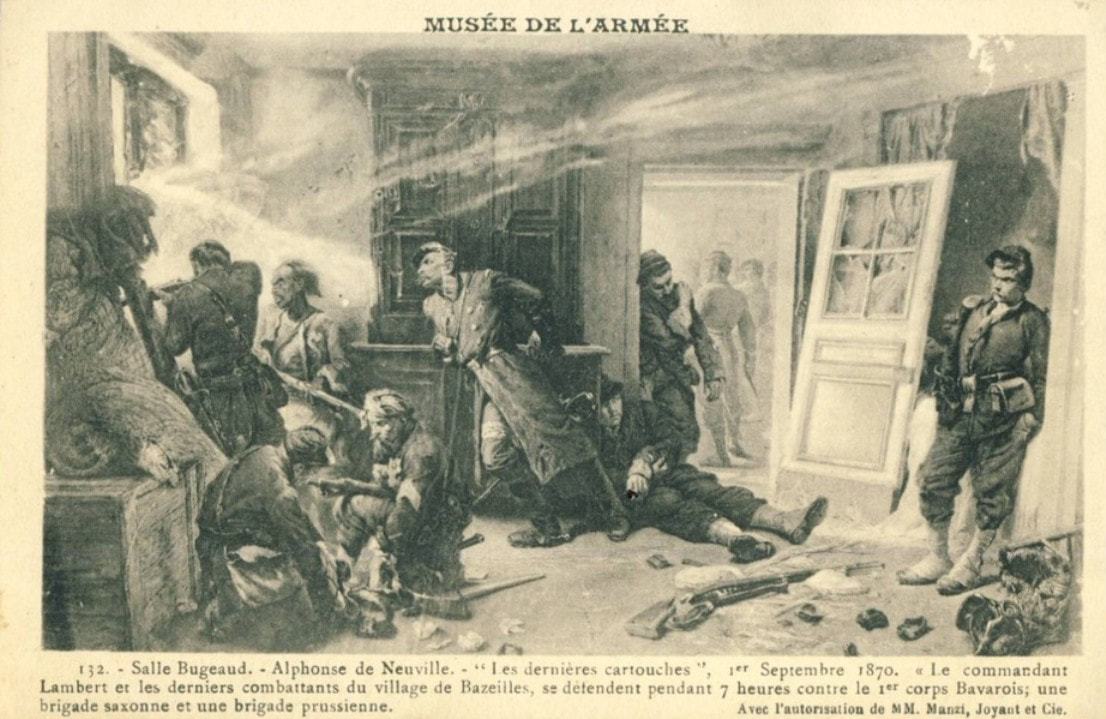

The most recent events evoked in the Hatot-Breteau historical views are two incidents from the Franco-Prussian war of 1870. Both films are restagings of paintings from the 1870s by Alphonse de Neuville:

Seguin's auteurism makes him say that Promio must have been interested in the war-subjects of Neuville's paintings because he had filmed several military views, but that is like saying Hatot was interested in Neuville's war paintings because Hatot had just been doing his military service. We would also need to say what inclination towards things military led Méliès to make a version of Les Dernières Cartouches in 1897 (below left), to explain why the German-born Albert-Fritz Kirchner, aka Léar, made a version in 1898 (below centre) and why at the same time the Pathé company made its version (below right):

The fact is that the subject was consistently popular. In July 1897 a production of the play Les Champairol at the Théâtre de la République included a tableau re-enacting Neuville's painting, and in 1903 Jules Mary's play Les Dernières Cartouches, based on his novelisation of the painting, played at the Ambigu-Comique:

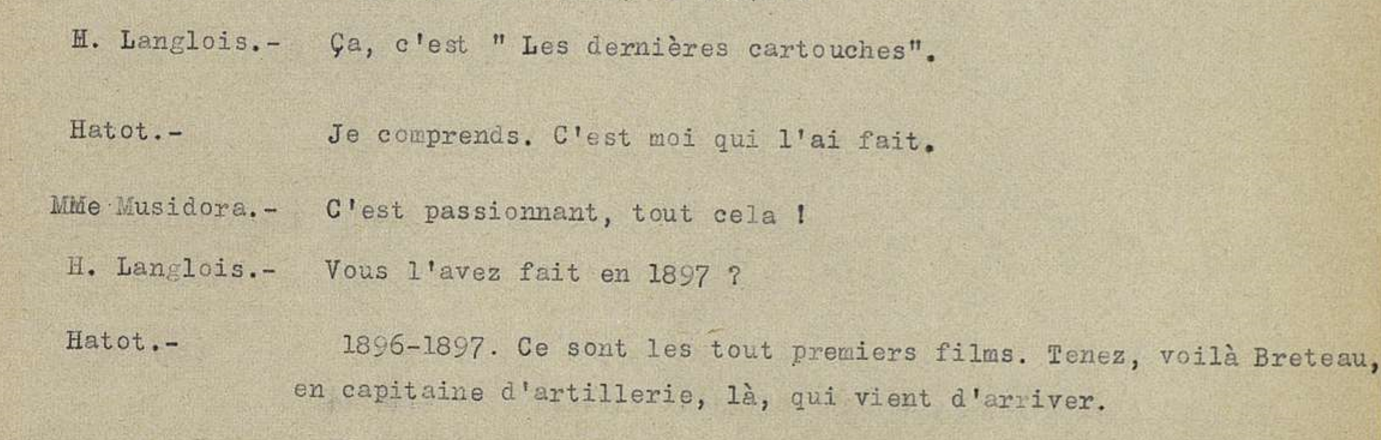

Hatot is very clear that Les Dernières Cartouches was made by him and Breteau, with Breteau also as actor:

It is nicely emblematic of the position I take regarding the claims made for Promio's authorship of this and other Breteau-Hatot films that in those reminiscences Promio's name is consistently and creatively mistranscribed by the sténotypistes: Amiot, Bromiaud, Promiot...

Without claiming that Hatot and Breteau are the réalisateurs of the films I have been discussing, when they are only the metteurs-en-scène, I think it would be a good thing if those films were not so often attributed to Promio, since he was only the opérateur. And it would also be good if Jambon were not so often credited as the décorateur of those films, when what credit there is should go to that now-forgotten peintre-ornemaniste, Pierre Comy.

Without claiming that Hatot and Breteau are the réalisateurs of the films I have been discussing, when they are only the metteurs-en-scène, I think it would be a good thing if those films were not so often attributed to Promio, since he was only the opérateur. And it would also be good if Jambon were not so often credited as the décorateur of those films, when what credit there is should go to that now-forgotten peintre-ornemaniste, Pierre Comy.

Appendix 1: Hatot with Lumière on the Boulevard de Strasbourg, 1896

The Théâtre des Fantaisies Nouvelles was at 32 Boulevard des Strasbourg. In July 1898 it started operating as a cinema 'for the summer', I think only in the afternoons. In this photograph, kindly provided by Marion and Philippe Jacquier, the man on the left is the Lumière operator Gabriel Veyre:

The films playing that I can decipher seem to be all Gaumont films from 1898, many of them attributable to Gaston Breteau: Rouget de L'Isle chantant La Marseillaise, Explosion du croiseur Le Merimac, Bonaparte au pont d'Arcole, Surprise d'une maison au petit jour, Le Château du Diable, Filous et Gendarmes, Le Nègre et le Maçon, l'Ahurissement d'un cocher, Déménagement à la cloche de bois, Les Tribulations de Mme Pipelet, Les Gendarmes au vert peints.

Though Le Château du Diable looks like an alternative title for Méliès's Le Manoir du Diable, I'm inclined to think that this must be a Gaumont film like the others, in which case it can only be Les Métamorphoses de Satan. I've not come across the title Filous et Gendarmes anywhere, but if it is an 1898 Gaumont film it can only be Les Cambrioleurs.

It looks like Breteau's arrangement with Pierre Comy for the use of décors had as quid pro quo the screening of Gaumont films at Comy's father's theatre.

This must be in July 1898, if the reference to the 'Fête Nationale' and the dates of the films advertised are anything to go by.

Though Le Château du Diable looks like an alternative title for Méliès's Le Manoir du Diable, I'm inclined to think that this must be a Gaumont film like the others, in which case it can only be Les Métamorphoses de Satan. I've not come across the title Filous et Gendarmes anywhere, but if it is an 1898 Gaumont film it can only be Les Cambrioleurs.

It looks like Breteau's arrangement with Pierre Comy for the use of décors had as quid pro quo the screening of Gaumont films at Comy's father's theatre.

This must be in July 1898, if the reference to the 'Fête Nationale' and the dates of the films advertised are anything to go by.

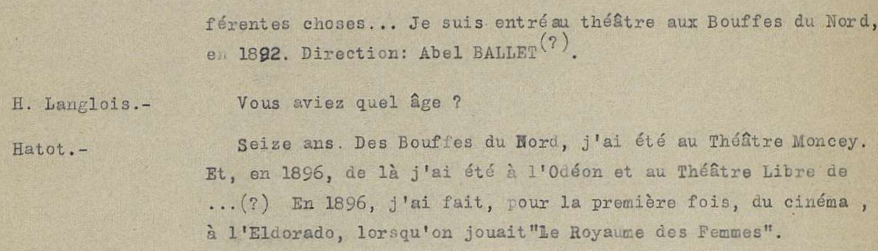

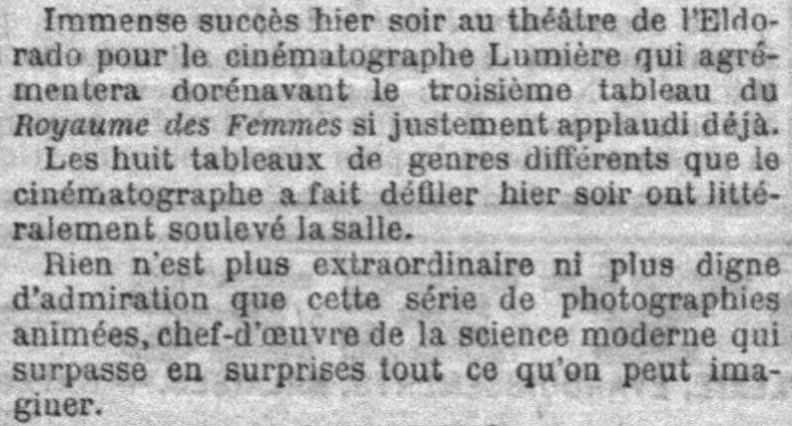

The Théâtre des Fantaisies Nouvelles was one of several competing establishments on the Boulevard de Strasbourg; its main rival was the Eldorado, at no. 4:

Talking about his early career, Hatot says that his first involvement with cinema was in 1896, at the Eldorado, when the show 'The Kingdom of Women' was on:

|

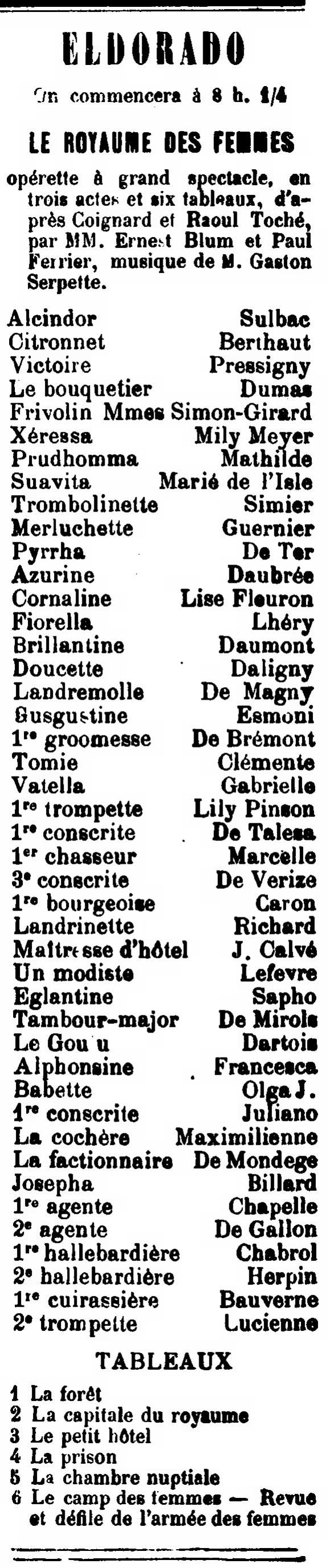

Le Royaume des femmes was a musical spectacle that ran at the Eldorado from February to May 1896. I don't know what rôle Hatot played in the production but he doesn't appear to have been in the cast, which was listed in full by L'Orchestre (right).

On the other hand, the rôle of the cinema in that production is well-documented. At the end of March, newspapers noted the addition to the show of 'eight tableaux of different genres' from the Lumière cinematograph: |

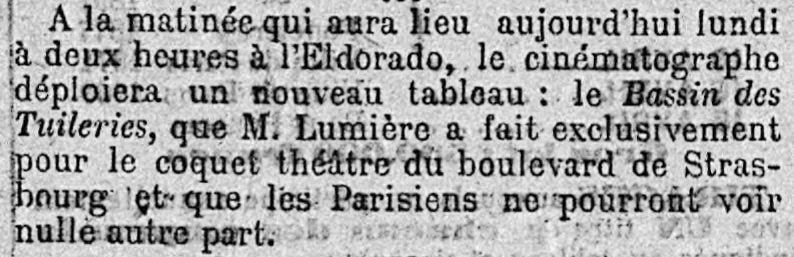

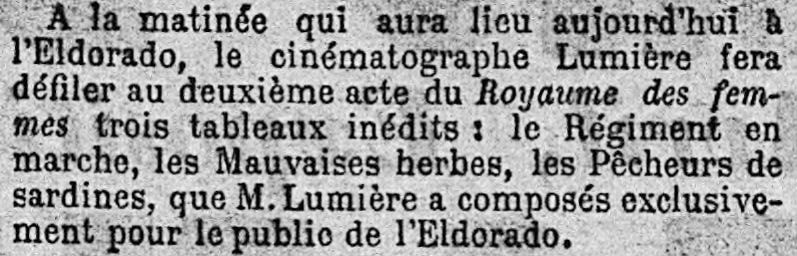

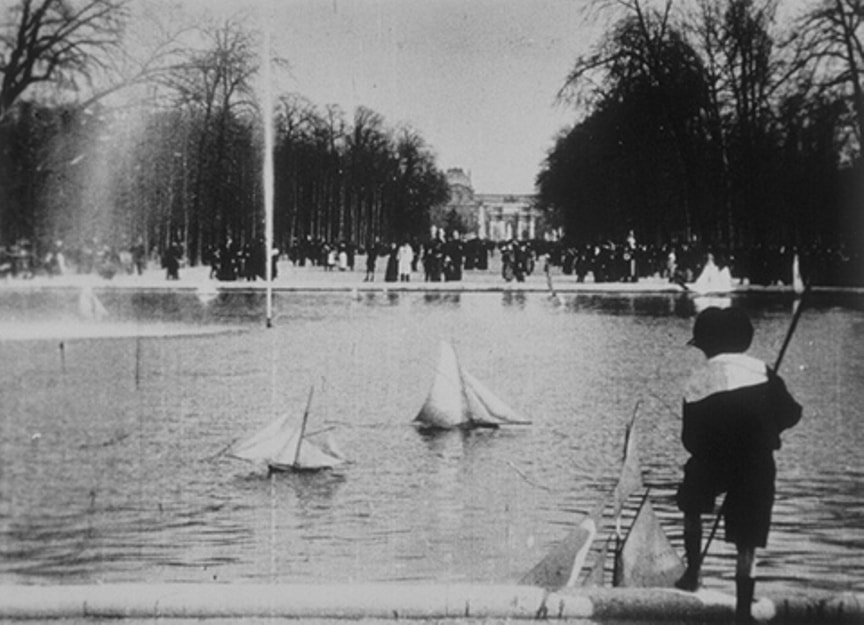

I haven't yet found an indication of which eight films were initially shown. Later news items describe additions to the programme, as when on April 6th Le Petit Journal announced that a new tableau would be added, Le Bassin des Tuileries, 'which M. Lumière has made especially for the charming little theatre on the Boulevard de Strasbourg, and which Parisians will not be able to see anywhere else'. On April 12th the same newspaper announced the addition of a further three tableaux: Le Régiment en marche, Les Mauvaise herbes and Les Pêcheurs de sardines, also 'composed exclusively for the Eldorado's public':

By April 15th, apparently in response to public demand, the Cinématographe's involvement with the Eldorado had increased exponentially, with a daily non-stop programme of films, starting either at 10.00 or 14.00 (press reports differ) and finishing at 18.00.

I would like to discover what Hatot meant by having 'fait du cinéma' in this context. I don't think he can have been the projectionist, because he says that when he and Breteau were staging films a year later 'we didn't know what we were doing, we didn't know what the cinematograph was, we didn't know what was inside the machine'.

Is it possible he meant that he was actually in one of the films that were projected? It would have to be a fiction, and I would have thought it would have to be a film made in Paris - there's no suggestion anywhere that his involvement with the Lumière company took him to Lyon. But I am not sure which are the Paris-made Lumière films requiring an actor from before April 1896.

This is, I think, an investigation for another time.

Is it possible he meant that he was actually in one of the films that were projected? It would have to be a fiction, and I would have thought it would have to be a film made in Paris - there's no suggestion anywhere that his involvement with the Lumière company took him to Lyon. But I am not sure which are the Paris-made Lumière films requiring an actor from before April 1896.

This is, I think, an investigation for another time.

Appendix 2: Hatot-Breteau films for Lumière

|

1897:

Assassinat de Kléber Assasinat du Duc de Guise Barbebleue Bataille d'enfants à coups d'oreillers Les Boxeurs et le spectateur trop curieux puni Le Charpentier maladroit Chez le cordonnier Chez le juge de paix Colleurs d'affiches Danseur russe La Défense du drapeau Dentiste Les Dernières Cartouches Les Deux Ivrognes Entrevue de Napoléon et du Pape Faust: apparition de Méphistophélès Faust: métamorphose de Faust et apparition de Marguerite Jury de peinture |

La Mort de Charles premier La Mort de Marat La Mort de Robespierre Napoléon et la sentinelle Néron essayant des poisons sur des esclaves Nounou et soldats Scène chez l'antiquaire La Signature du traité de Campo-Formio Les Tribulations d'une concierge Une farce à la chambrée Voyageur et voleurs 1898: Combat sur la voie ferrée L'Exécution de Jeanne d'Arc Le Marchand de confetti Le Marchand de marrons Poursuite sur les toits La Vie et la Passion de Jésus-Christ - 13 tableaux |

At the beginning of the first of the 1948 interviews Hatot says the following films are by him: Bataille de femmes; Colin Maillard; Farce et pot de peinture; Le Faux cul-de-jatte; Le Lit en bascule:

In the second interview, when they watch some of the films, he says he is mistaken about Faux cul de jatte, that it was made in Lyon and so not by him. There is evidence that confirms it as a 'Lyonnais' film, and evidence likewise for the four others, so it doesn't look like they could have been made by Hatot.

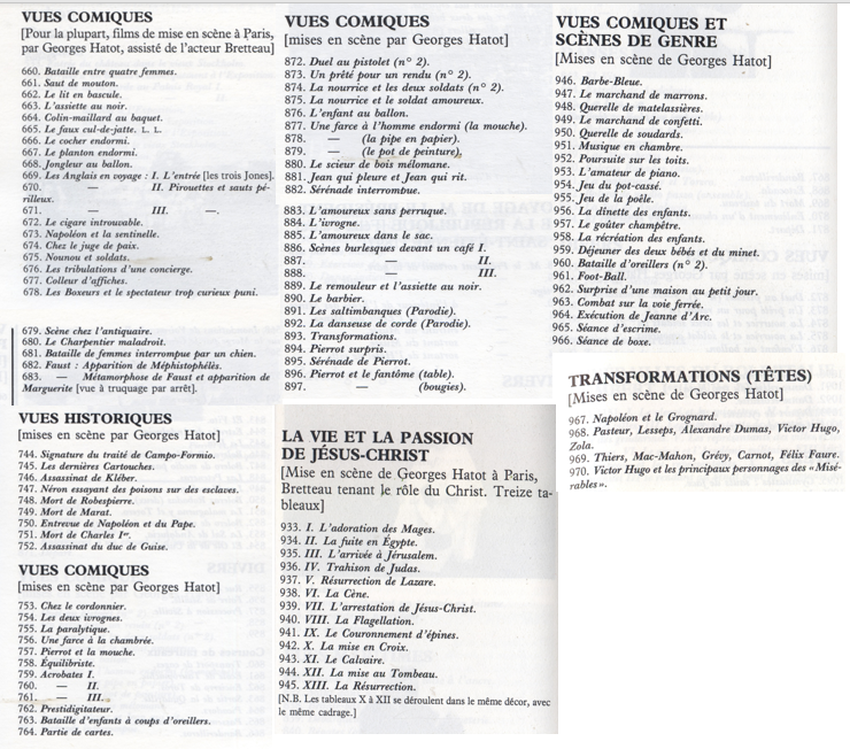

In 1947, in the Histoire générale du cinéma, Georges Sadoul wasn't aware that Hatot had made the films discussed in this post - this was before the interviews with Langlois and Musidora. By the time he wrote his book on Louis Lumière in 1964, Sadoul had somewhat over-compensated, crediting Hatot with a total of 108 contributions to the Lumière filmography:

Many of these can be identified as Lyon-made, and some (e.g. those with Trewey) are known to have been made at la Ciotat.

To be fair to Sadoul, for the first group of 'Vues comiques' he did say that they are 'mostly' made by Hatot, and by adding the letters 'L.L.' he attributed Le Faux cul-de-jatte to Louis Lumière.

Knowing that some films of a certain genre were made by Hatot at a certain time, Sadoul concluded that all of the films of those genres made at that time were his, constituting for him a veritable oeuvre, though Sadoul didn't, thankfully, pursue an auteurist reading of this corpus, chiefly because in this book the auteur he had fixed on was Louis Lumière. And thankfully no one else has, at least yet, made an auteur of Hatot circa 1897.

To be fair to Sadoul, for the first group of 'Vues comiques' he did say that they are 'mostly' made by Hatot, and by adding the letters 'L.L.' he attributed Le Faux cul-de-jatte to Louis Lumière.

Knowing that some films of a certain genre were made by Hatot at a certain time, Sadoul concluded that all of the films of those genres made at that time were his, constituting for him a veritable oeuvre, though Sadoul didn't, thankfully, pursue an auteurist reading of this corpus, chiefly because in this book the auteur he had fixed on was Louis Lumière. And thankfully no one else has, at least yet, made an auteur of Hatot circa 1897.

Appendix 3: Breteau-Hatot films for Gaumont

Of the films that Breteau made for Gaumont, mostly without Hatot, I have already mentioned L'Aveugle fin de siècle, Les Cambrioleurs, Les Métamorphoses de Satan and Quatre jours de clou, as well as La Vie du Christ. Les Tribulations de Mme Pipelet has a décor that appears to have been used in the Lumière film Le Marchand de marrons, suggesting that Breteau made both.

In his chapter entitled 'Alice Guy a-t-il existé', Gianati enumerates forty fiction films in the Gaumont catalogue of 1900 that were made by the Breteau-Hatot team (nos 115-151, 154, 173, 175). If he were right, and not counting the Christ film, this would be the complete list of their films for Gaumont, all made at the Rue du Surmelin site between June and October 1898:

In his chapter entitled 'Alice Guy a-t-il existé', Gianati enumerates forty fiction films in the Gaumont catalogue of 1900 that were made by the Breteau-Hatot team (nos 115-151, 154, 173, 175). If he were right, and not counting the Christ film, this would be the complete list of their films for Gaumont, all made at the Rue du Surmelin site between June and October 1898:

|

L'Aveugle fin de siècle

Barbe bleue Bonaparte au pont d'Arcole Les Cambrioleurs Chez le dentiste Chez le magnétiseur Chez le photographe Le Cocher de fiacre endormi Les Colleurs d'affiche Combat sur la voie ferrée Déménagement à la cloche de bois Don Quichotte Duel de clowns En conciliation Entre deux vins Episode de la guerre hispano-américaine Explosion du Merrimac Les Farces de Jocko Gendarmes au vert peints Guet-apens sous François 1er |

Idylle interrompue

Janville Je vous y prrrends! Leçon de boxe Marchande de frites et cocher de fiacre Les Métamorphoses de Satan La Mort de Lannes Le Nègre et les Maçons Noce comique L'Ours et la Sentinelle Pêche miraculeuse Pioupiou et Nounou Les Pompiers de Nanterre Quatre jours de clou Querelle de soudards Scène d'escamotage Surprise d'une maison au petit jour Les Surprises d'un perruquier Les Tribulations de Mme Pipelet Un duel néfaste |

In his lecture on Guy he also discusses L'Utilité des rayons X (no. 155) as a Breteau film, on the basis that Breteau is in it:

Though I prefer the argument from decor, I am persuaded by Gianati's claim that a Gaumont film is Breteau's when he is in it. Breteau is also in these two films, Chez le magnétiseur and Scène d'escamotage, the first time as the woman, the second as the man:

I'm not sure I recognise Breteau here in Rouget de l'Isle chantant la Marseillaise, but I do recognise here the décor used in Chez le magnétiseur and Scène d'escamotage, so this is one more Gaumont film that should be credited to Breteau:

In February 2016 Laurent Mannoni, Jacques Malthète and Maurice Gianati gave a presentation entitles '1896/2016: Lumière/Méliès: les débuts du spectacle cinématographique', in which the films of Hatot and Breteau were discussed. I wasn't there, so I'm afraid don't know if everything I have said here was already said then, or contradicted, or insome other way rendered redundant.

Here is a nicely coloured frame from Entrevue de Napoléon et du Pape, which was used in the pubicity for that presentation:

Here is a nicely coloured frame from Entrevue de Napoléon et du Pape, which was used in the pubicity for that presentation:

Many thanks to Mariann Lewinsky Sträuli and Dominique Moustacchi for discussing these things with me, and for all the information provided.

My thanks also to Marion and Philippe Jacquier for permission to use the photograph of Gabriel Veyre in front of the Fantaisies Nouvelles.

My thanks also to Marion and Philippe Jacquier for permission to use the photograph of Gabriel Veyre in front of the Fantaisies Nouvelles.

References and sources

Alice Guy, The Memoirs of Alice Guy Blaché, translated by Roberta and Simone Blaché, edited by Anthony Slide (Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, 1996)

Maurice Gianati and Laurent Mannoni, Alice Guy, Léon Gaumont et les débuts du film sonore (John Libbey: New Barnet, 2012) - see also 'Alice Guy a-t-elle existé', conférence de Maurice Guanati, 2010

Alison McMahan, Alice Guy Blaché: Lost Visionary of the Cinema (New York: Continuum, 2002)

Georges Sadoul, Histoire générale du cinéma: les pionniers du cinéma 1897-1909 (Paris: Denoël, 1947)

Georges Sadoul, Lumière et Méliès (Paris: Lherminier, 1985) - a new edition of Louis Lumière (Paris: Seghers, 1964)

Jean-Claude Seguin, Alexandre Promio, ou les énigmes de la lumière (Paris: Harmattan, 1999)

Archives de Paris - plans parcellaires

Catalogue Lumière

Ciné-ressources - archives

CNC AFF

Delcampe - cartes postales

Gallica (BNF)

Le Grimh

Musées de Paris collections

Catalogue Lumière

Ciné-ressources - archives

CNC AFF

Delcampe - cartes postales

Gallica (BNF)

Le Grimh

Musées de Paris collections