Shot in April and May 1960, Le Petit Soldat is apparently a record of events two years earlier, the time of the insurrection in Algiers that led, eventually, to De Gaulle’s return to power and to the establishment of the Fifth Republic. It is one of very few films by Godard to be formally set in an earlier time; in 1960 he had categorically rejected the idea of making films about the past: 'Why not make something current, why do you have to consider present events as something taboo? A film is out of date when it doesn’t give a true picture of the era it was made in. (…) I would consider it indecent to make a film today about the resistance. (…) Doing it now is dishonest, impure, and fabricated' (Godard 1972: 26).

Le Petit Soldat is set in the past. This setting is a feature of the narrative, delivered by the narrator, voice off: ‘Geneva, 13 May 1958’. Against this, the vérité documented in the film is a different time, that of filming, April and May 1960. Datable material proliferates, and all of it relocates the film from May 1958 to April 1960. There is a case to be made for discounting the chronological specificity of the found materials, for not seeking period authenticity in a period film by Godard. He himself, in an interview with L’Express, says that a shot of that magazine’s banned issue about ‘Hitler: twenty years after’ was included because it happened to come out, in Switzerland, at the time of filming: ‘It was perfect timing!’. But he adds: ‘I imagine the public will see this as a gag, at best; but for me, every detail is always filled with little hidden meanings’ (Godard 1972: 27).

Le Petit Soldat is set in the past. This setting is a feature of the narrative, delivered by the narrator, voice off: ‘Geneva, 13 May 1958’. Against this, the vérité documented in the film is a different time, that of filming, April and May 1960. Datable material proliferates, and all of it relocates the film from May 1958 to April 1960. There is a case to be made for discounting the chronological specificity of the found materials, for not seeking period authenticity in a period film by Godard. He himself, in an interview with L’Express, says that a shot of that magazine’s banned issue about ‘Hitler: twenty years after’ was included because it happened to come out, in Switzerland, at the time of filming: ‘It was perfect timing!’. But he adds: ‘I imagine the public will see this as a gag, at best; but for me, every detail is always filled with little hidden meanings’ (Godard 1972: 27).

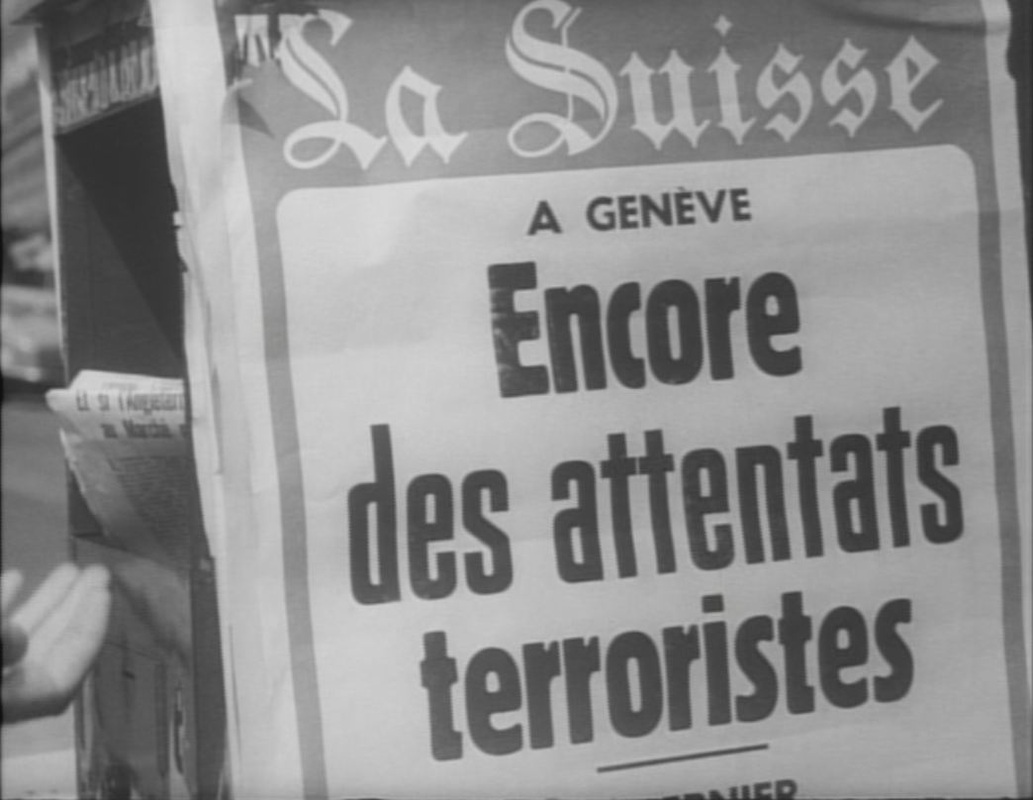

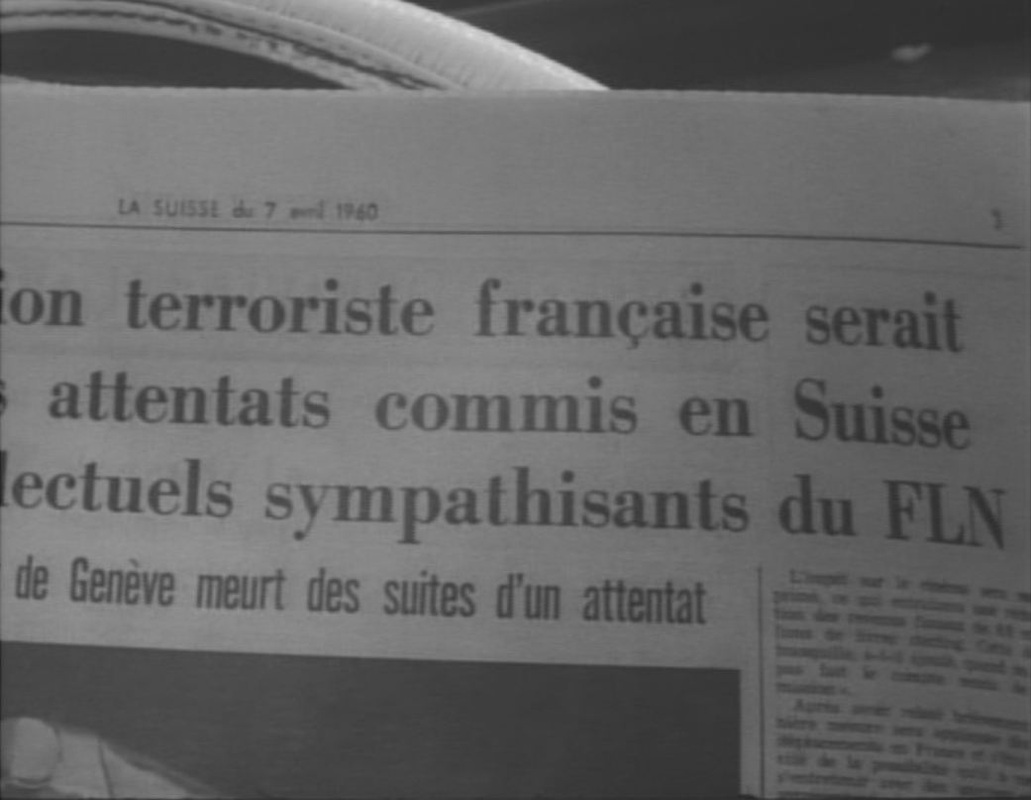

Perhaps the deepest repository of hidden meanings in Le Petit Soldat is that Daney-moment when Bruno Forestier buys the paper to read of ‘Fresh terrorist attacks in Geneva’, with the date at the top of the page, April 7 1960:

This looks very much like filming the paper of the day of the shoot, April 7 being a few days into filming. Curious about the detail of the terrorist attacks that trigger the action of the film, I rushed to the archives of La Suisse newspaper to read the story. But the newspaper is a fake: the news in Geneva that day was nothing like so sensational. There were certainly no terrorist bombs being planted in Geneva in early 1960. The page is a montage, serving the narrative’s need for terrorist activity of this kind, at this time, in this city.

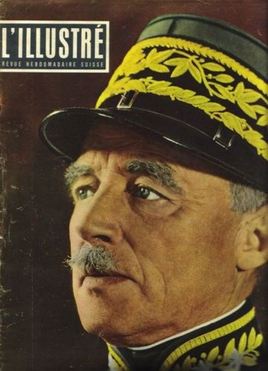

However, that need alone wouldn’t require that we see the date of the newspaper – on the contrary, if the time of the narrative is May 1958, it would be better simply not to include in frame the date at the top of the page. It can only be that we are to read the date, and read something into it. A clue comes five minutes later, when a man on a train is seen reading L’Illustré, the Swiss Paris Match, with the face of General Guisan on the cover.

However, that need alone wouldn’t require that we see the date of the newspaper – on the contrary, if the time of the narrative is May 1958, it would be better simply not to include in frame the date at the top of the page. It can only be that we are to read the date, and read something into it. A clue comes five minutes later, when a man on a train is seen reading L’Illustré, the Swiss Paris Match, with the face of General Guisan on the cover.

Guisan was the general in charge of the defence of Switzerland during World War Two, a national hero (for the French-speaking Swiss in particular). Guisan died on April 7 1960, the date on the newspaper bought by Bruno. This

image of Guisan not only goes against the May 1958 chronology of the narrative,

it also twists the April 1960 chronology: Bruno is supposed to have bought a

newspaper on April 7; a few hours later he is in the train, where another agent

is reading the ‘General Guisan’ commemorative issue of L’Illustré (which came out on April 21), reading, that is, a

magazine mourning the death of the great general some six hours before he

actually dies.

The opening of the film, then, sets against each other May 13 1958 and April 7 1960, significant dates for the eminent generals of two nations – De Gaulle and Guisan – inviting us to read them against each other. Inevitably, against the great soldier and statesman De Gaulle, Guisan is a ‘petit soldat’.

The two times are not resolved: the narrative unfolds as if it began on May 13 1958, but is constantly illustrated with images from April 1960. The reference to 1958 is sustained by sounds, the succession of radio broadcasts that punctuate the film. There are sixteen of them, each time motivated from within the narrative by characters listening to the radio. These broadcasts all refer explicitly to insurrection in Algiers, and through references to specific political figures and events several of the broadcasts can be dated to the week following May 13 1958.

Several but not all. A number introduce a third time frame, referring not to May ‘58 but to the insurrection in Algiers that occurred almost two years later, in January 1960: the ‘semaine des barricades’. This is, we remember, the action that prompts the trials taking place in Paris in November 1960, during the shooting of Une femme est une femme. The insurrectionists had intended to revive the spirit of May ‘58, but without this time falling for the lies of De Gaulle and his promise to defend ‘L’Algérie française’.

The two times are not resolved: the narrative unfolds as if it began on May 13 1958, but is constantly illustrated with images from April 1960. The reference to 1958 is sustained by sounds, the succession of radio broadcasts that punctuate the film. There are sixteen of them, each time motivated from within the narrative by characters listening to the radio. These broadcasts all refer explicitly to insurrection in Algiers, and through references to specific political figures and events several of the broadcasts can be dated to the week following May 13 1958.

Several but not all. A number introduce a third time frame, referring not to May ‘58 but to the insurrection in Algiers that occurred almost two years later, in January 1960: the ‘semaine des barricades’. This is, we remember, the action that prompts the trials taking place in Paris in November 1960, during the shooting of Une femme est une femme. The insurrectionists had intended to revive the spirit of May ‘58, but without this time falling for the lies of De Gaulle and his promise to defend ‘L’Algérie française’.

The mixing of reference to the two insurrections is a reading of one against the other, a history lesson in montage, and, paradoxically, a means for making political comment at a precise point in time. Had Le Petit Soldat been released as planned in Autumn 1960, it would have been playing in Paris as the trial opened, and the press coverage of the trial would have supplied the film’s audience with the means necessary to identify exactly the allusions made to the January events. Through the immediacy of the film’s political references it would have been read, exactly, as a film of its time. As it is, Le Petit Soldat was banned for more than two years. On release in January 1963, after more serious insurrections, and after the eventual end of the Algerian war, it had missed its moment, its point in time.

One effect of these missed readings is a recurrent confusion about the nature of the ‘anti-terrorist commando’ to which Bruno belongs. It is commonly identified with the OAS, the Organisation Armée Secrète, but this is not Pierrot le fou, where the inscription ‘OASIS’ on the wall of Marianne’s apartment invites us to associate the violence represented in that film with the actions of colonel Godard and company. (I know of no explicit reference in Jean-Luc Godard’s work to the coincidence of his name with that of the OAS’s head of operations, Colonel Yves Godard.)

Le Petit Soldat was made a year before the creation of the OAS. (Though there were secret contacts between the French secret services and OAS representatives in February 1960, the consensus among historians is that the OAS was not active until, at the earliest, late 1960.)

|

The organisation to whch Bruno Forestier belongs in Le Petit Soldat is, as Noël Simsolo (1970: 102) has pointed out, ‘la main rouge’ (‘the red hand’), the semi-mythical agency created by the French secret services (SDECE) to take the blame for government-sponsored terrorist actions. For information on ‘la main rouge’ see Méléro (1997) and Faligot and Krop (1985).

The car-bombing of Professor Lachenal in the film is exactly the kind of act for which ‘la main rouge’ was held responsible, especially after the government’s attention turned from the FLN’s arms-suppliers to mere apologists and sympathisers. |

In March 1960, for example, two professors at the University of Liège received ‘main rouge’ letter-bombs, and one of them, Laperche, was killed. The

bombs were hidden in copies of Hafid Keramane’s La Pacification, livre noir de 6 années de guerre en Algérie,

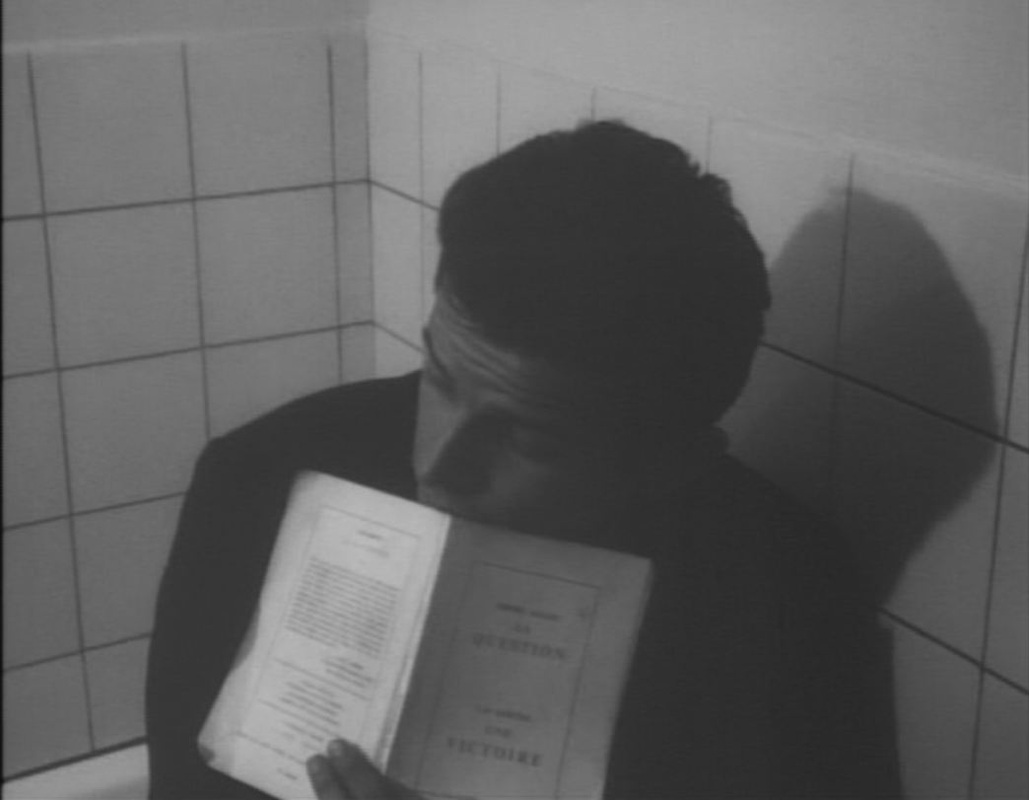

published that month in Lausanne by Nils Andersson’s press La Cité. In Le Petit Soldat we see FLN agents

reading from another book published by Andersson, Henri Alleg’s La Question.

A clearer indication is found in the name of Forestier’s immediate superior in the group, Jacques-Aurélien Mercier. This name is a typically Godardian rebus: ‘Jacques’ is a trace of the real, taken from the name of the actor, Henri-Jacques Huet (just as Paul Beauvais keeps the name Paul in the film); ‘Aurélien’ is from Aragon’s novel of that name, joining several other references to Aragon in this film (and in almost all Godard’s films of the sixties); ‘Mercier’ points us towards ‘la main rouge’, whose supposed head of operations was Colonel Marcel-André Mercier, otherwise known as ‘le petit Mercier’. Though the Mercier character in the film hasn’t the high rank of his namesake, his career is an emblematic résumé of the activities of ‘la main rouge’. Like many ‘main rouge’ agents, he is a veteran of the war in Indo-China: ‘We find his trace again in ‘57 in Rotterdam, when the cargo-ship Aramis is blown up, in ‘59 in Frankfurt when Professor Dietrich is assassinated. Now he is in Geneva.’ This cv echoes specific action attributed to ‘la main rouge’, like the sinking in 1958 in Hamburg of the cargo ship Atlas, belonging to the FLN’s arms-supplier Peuchart, and the car-bombing in 1959, in Frankfurt, of Peuchart himself. It also evokes the fact that colonel Mercier was based in Switzerland until his expulsion in 1957, as well as the assassination in Geneva of arms dealers in 1958 and 1959.

The only other detail given in the film that might identify a referent is the mention that the anti-terrorist cell is funded by ‘a former Poujadist deputé who had his moment of glory under Vichy’. This is in part a gag, since the funder of the cell is played by the funder of the film, Georges de Beauregard, but there is probably, among the fifty députés elected on Poujade’s ticket in 1956, one who had his moment under Vichy, recognisable in the remark. We can rule out Jean-Marie Le Pen, already an ex-Poujadist but too young to have done much under Vichy. He is, however, involved with Le Petit Soldat as the député who called for the expulsion of the foreigner Godard for making this film. The name of another ‘député poujadiste’, Berthommier, is mentioned in one of the several radio broadcasts heard throughout the film, but he was not much older than Le Pen.

The publicity accorded the actions of ‘la main rouge’ would have made the association more obvious in 1960, and the association gives credence still to the actions represented in Le Petit Soldat, even if in Geneva in 1960 no professors were blown up or radio journalists gunned down.

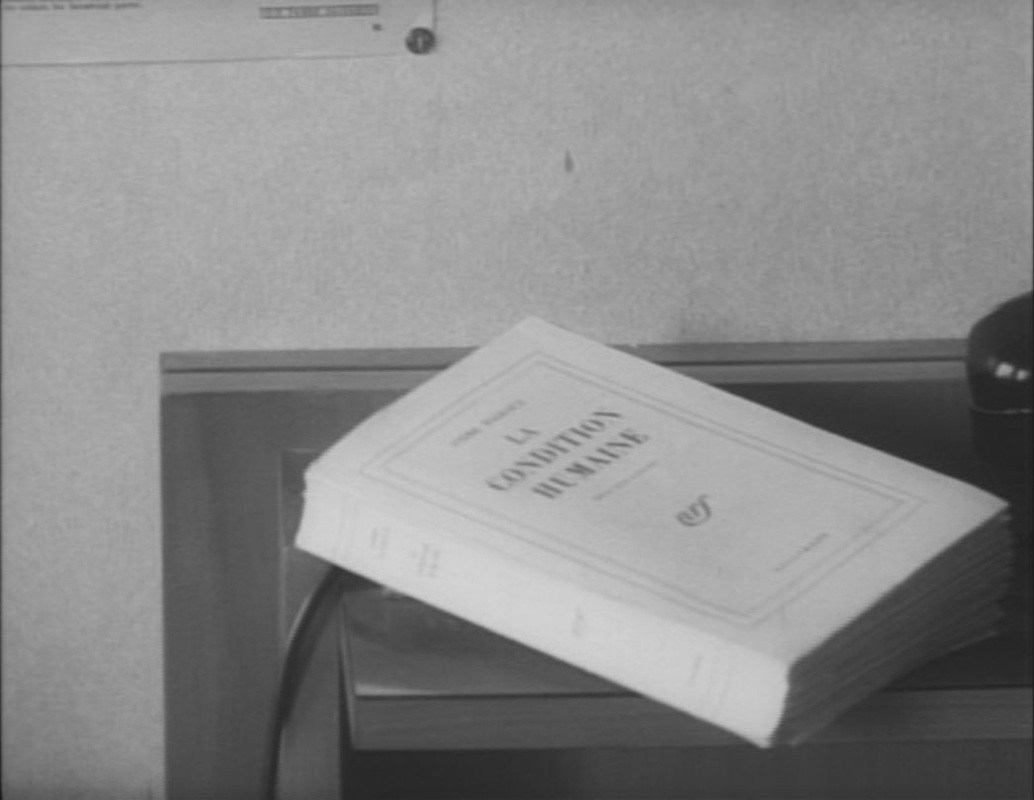

Le Petit Soldat is one of Godard’s most chronologically complex films. It appears all the more complex when the chronological specificity of its three narrative times is read against the recurrent memory in the film of earlier times: the 1914-1918 war, the Civil War in Spain and the period 1940-44 in France. These references include the opening (mis)quotation of lines from Aragon’s ‘Les lilas et les roses’, an allusion to Drieu la Rochelle’s suicide, and several references to Malraux (a copy of La Condition humaine on a bedside table, a still from Espoir on the wall above, etc.).

In the films that come after Le Petit Soldat, reference to the Algerian war is more straightforward, relatively, because the films are not made to carry the past as an extra burden. By 1965, and Pierrot le fou, the Algerian war is not a parallel chronology, but itself a matter for memory: ‘it was like in the Algerian war’, says Ferdinand (Belmondo), twice; when he is tortured by the same means used in Le Petit Soldat, the cinematic intertextuality helps us share this nostalgia (earlier in the film we see a poster for Le Petit Soldat on the wall of Marianne’s apartment); and the graffiti in Pierrot le fou that should read OAS – Organisation Armée Secrète – has been transformed into OASIS… This derisory escapism effaces the history of only two years before.

Another parallel history takes over, that of the Vietnam war. But in most of Pierrot le fou, and consistently in the films that follow, reference to Vietnam is of a different order: emblematic, iconic, less bound by precise chronology, more ‘pop’. An early sequence illustrates the transition. Ferdinand and Marianne (Karina) are in a car listening to the radio, a report of the death of 115 Vietcong. Marianne comments: ‘It’s terrible how anonymous it is. (...) They say 115 maquisards and it means nothing, but each one is a man, and we know nothing about him (...)’ (Godard 1969: 76; my translation). As in Le Petit Soldat, the radio is the medium, but here the event mentioned doesn’t serve to situate the narrative within a specific historical chronology. Rather, the narrative chronology makes the event emblematic: the scene is supposed to take place on July 14.

For a fuller discussion of chronology in Godard's first films, see the essay from which the above was adapted, here - first published in Studies in French Cinema 3:2 (2003).

References

- Alleg, H. (1958), La Question, Lausanne, La Cité

- Faligot, R. and P. Krop (1985), La Piscine. Les services secrets français 1944-1984, Paris, Seuil

- Godard, J.-L. (1972), ‘Learning not to be bitter: interview with Jean-Luc Godard on Le Petit Soldat by Michèle Manceaux’ [from L’Express, 16.6.1960], Focus on Godard (ed. R. S. Brown), Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, pp.25-27

- Méléro, A. (1997), La Main rouge. L’armée secrète de la République, Monaco, Editions du Rocher

- Simsolo, N. (1970), ‘Le Petit Soldat’, Image et son 244, pp. 101-106