Où est Max?

Filmmaking in and around the Pathé studios in Vincennes, c.1911

Filmmaking in and around the Pathé studios in Vincennes, c.1911

1/ home and abroad

|

Before departing for Chicago in 1916, Max Linder was already very well travelled. He had been several times to the French Riviera (Max à Monaco, Le Hasard et l'Amour) and to the Alps (Max fait du ski, Max asthmatique). He had been seen on the banks of Lake Geneva (Max entre deux feux), in Berlin (Max professeur de tango) and in Barcelona (Max toreador).

(It is true that in Comment Max Linder fait le tour du monde, when he was supposed to be in China or Africa, he didn't actually go anywhere.) |

This piece is about Max at home, home being not - as a distant eye might think - Paris but Vincennes, the small town at the eastern edge of Paris that was home to the Pathé frères company, for which Max Linder made films between 1905 and 1916.

Max isn't often seen in Paris itself. His courtship of an American tourist leads to one exception in L'Anglais tel que Max le parle:

Max isn't often seen in Paris itself. His courtship of an American tourist leads to one exception in L'Anglais tel que Max le parle:

When he appears on the stage it is at a Paris theatre, the Alhambra, but we aren't shown the exterior, and the stage, wings and dressing room seem all to have been reconstructed in the 'théâtre de prises de vues', the Pathé studio at Vincennes:

Likewise for the interiors of locales that have Paris addresses, such as '60 avenue du Bois' (presumably '...de Boulogne') in Max pratique tous les sports or '26 avenue de l'Opéra' in Mari jaloux:

In the latter instance we do see the street outside as Max arrives at the address, but what we see is not the avenue de l'Opéra in Paris:

In the scenario for this film, the address is given as '20 rue de l'Opéra', so the intertitle may have been incorrectly reconstructed, but anyway the building at no. 20 is of the same type as no.26, and isn't what we see in the film. The street we see in the film is in Vincennes.

The same thing happens in Mariage forcé. Max's uncle lives in Paris, rue de la Fontaine au Roi, but the building we are shown as the uncle's residence is, again, in Vincennes:

The same thing happens in Mariage forcé. Max's uncle lives in Paris, rue de la Fontaine au Roi, but the building we are shown as the uncle's residence is, again, in Vincennes:

Vincennes locations such as the ones above have no difficulty in passing for Paris. In general a bourgeois apartment building in the one looks much like a bourgeois apartment building in the other, and Max's Parisian persona is not affected by his not being quite in Paris.

On one occasion at least Max identifies with Vincennes rather than Paris. In Peintre par amour he pretends to be an artist and assumes the pseudonym 'Léonard de Vincennes'.

Sometimes Vincennes can be recognised by its landmarks. Here are the town hall and the Pyramide du bois de Vincennes (it's actually an obelisk), both from Mariage forcé:

On one occasion at least Max identifies with Vincennes rather than Paris. In Peintre par amour he pretends to be an artist and assumes the pseudonym 'Léonard de Vincennes'.

Sometimes Vincennes can be recognised by its landmarks. Here are the town hall and the Pyramide du bois de Vincennes (it's actually an obelisk), both from Mariage forcé:

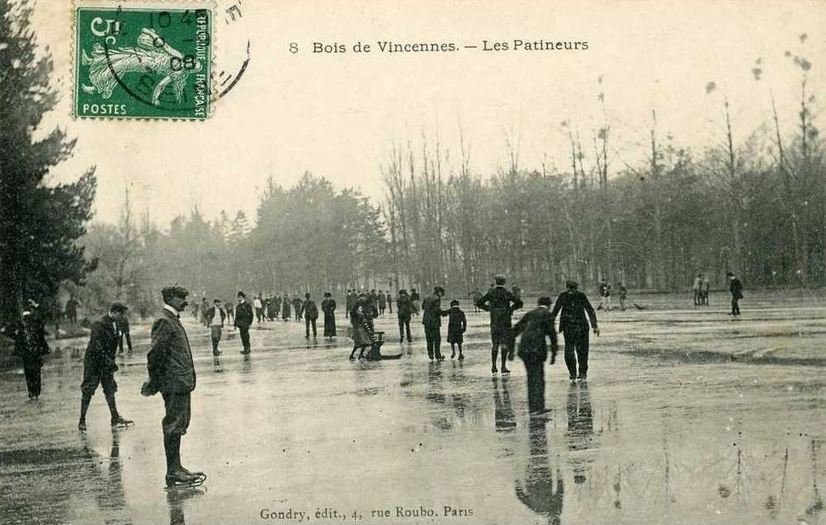

And the lake on which Max tries skating for the first time (Les Débuts d'un patineur) is recognisable, according to Pathé cataloguer Henri Bousquet, as lac Daumesnil in the Bois de Vincennes:

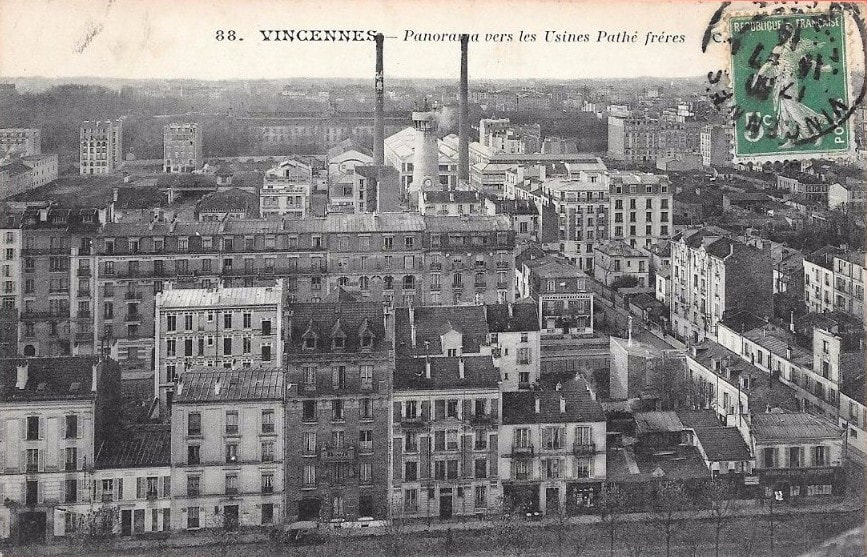

But mostly the Vincennes locations of Max's films would spark recognition in only a very small part of his worldwide audience. Most are recognisable only to Vincennois, and some only to those Vincennois familiar with a very specific sector of the town, the streets immediately around the Pathé factory. The next section of this post is about those streets, and about one street in particular.

2/ rue Louis Besquel

|

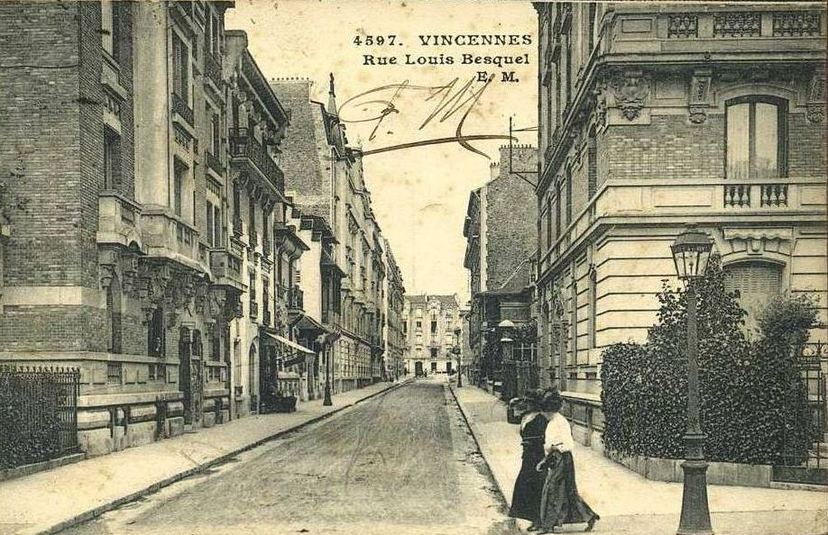

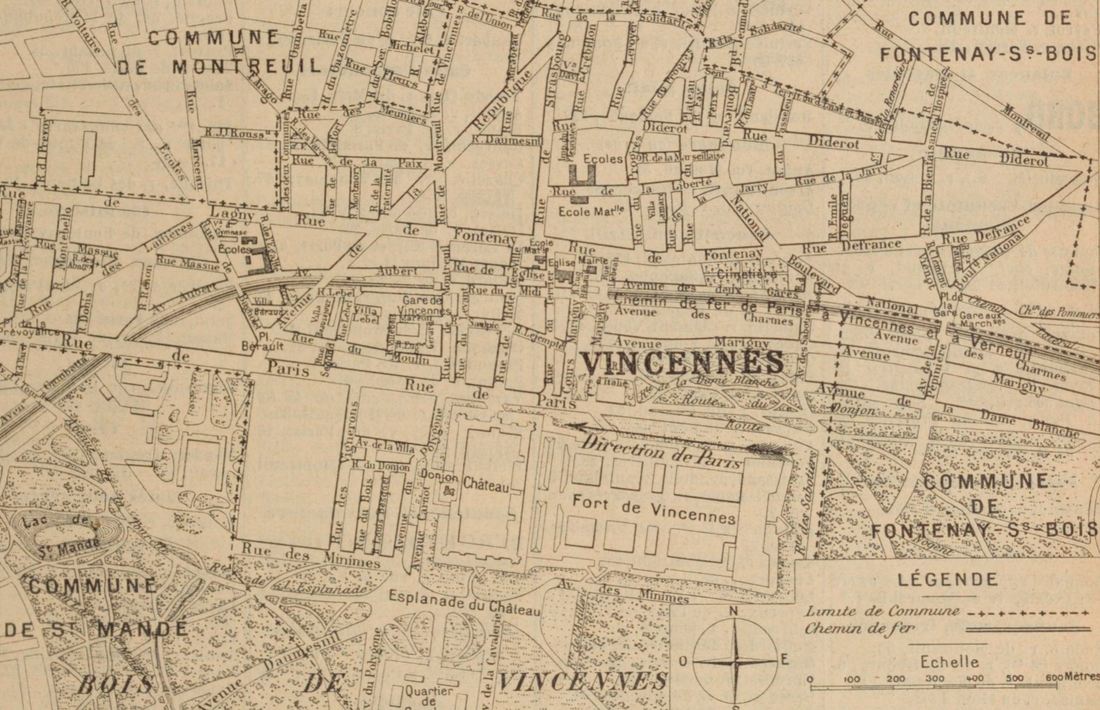

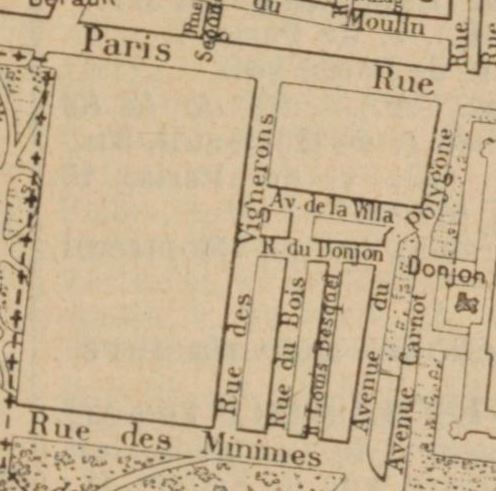

The street I am interested in is, on the map, the one running parallel to and between the rue du Bois and the avenue du Polygone, unidentified on this map perhaps because it had just been laid out and not yet named (it was laid out in 1903). This street's first point of interest, for us here, is its proximity to the Pathé factory and studios which, beginning to the right at 1 avenue du Polygone in 1896 (roughly by the 'n' in 'Avenue'), expanded in the new century onto the rue du Bois and the rue des Vignerons. |

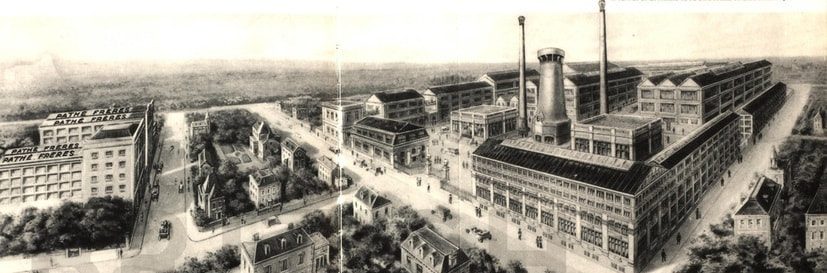

By 1910 the Pathé works looked like this:

The rue Louis Besquel is the next street along from the one at the bottom of the postcard below, with a terrace of apartment buildings and a free-standing villa at the end, where it meets the Rue du Donjon.

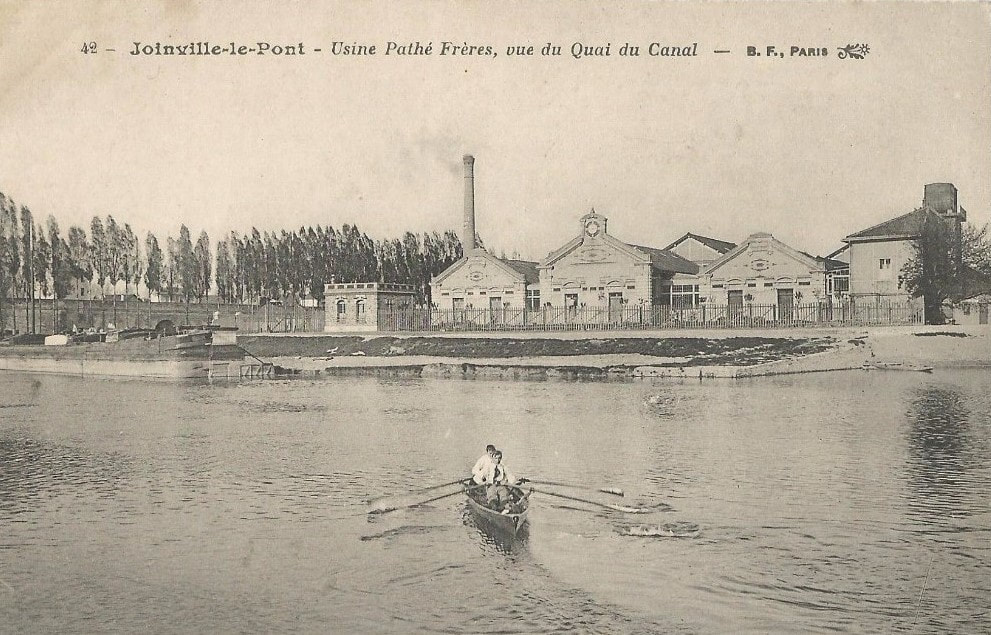

This street was developed by Georges Malo, a local architect-entrepreneur. Malo had designed Pathé buildings at Vincennes and Joinville-le-Pont. He was also commissioned by Pathé to adapt the Cirque d'Hiver in Paris for film screenings, and to provide the standard design for the 'Pathé-Exploitation' cinemas:

Malo's style was eclectic and, for some buildings, highly distinctive. Here are two examples of his work in other streets of Vincennes:

The first of these buildings was used in Ma fille n'épousera qu'un médium, from 1909. Malo's characteristic colour contrasts are well-enough represented in the tinted version:

The Mairie de Vincennes has published a detailed guide to the architecture of this sector, with much on the work of Georges Malo, accessible here (click on the pdf for the 'Parcours du patrimoine 5 -sud').

Architectural historian Patrick Urbain discusses here (in French) some of the distinctive features of Malo's work in the rue Louis Besquel, concentrating in particular on one very striking building, at number 28, dating from 1904:

Architectural historian Patrick Urbain discusses here (in French) some of the distinctive features of Malo's work in the rue Louis Besquel, concentrating in particular on one very striking building, at number 28, dating from 1904:

The whole street is remarkable, with apartment blocks and individual houses of different scale and style, but all using decorative brickwork and sculptural ornament. Malo has a penchant for contrasting materials, forms and colours:

Malo's street is largely intact, with a few additions made by others in the two decades after his first realisations (and one post WW2 building). For anyone interested in early twentieth-century French suburban architecture, walking down the rue Louis Besquel is a memorable experience.

The street is of great interest also to anyone interested in early twentieth-century French cinema. The direct answer to the question asked in the title of this piece - 'Where is Max?' - is that for a large part of the time Max was on the rue Louis Besquel. The street can be seen in twenty-one of the films I have been able to examine (about sixty), and Max can be seen going into, coming out of or running past at least thirteen of its thirty-two buildings. Several of these buildings appear in more than one film. The gallery below corresponds to a stroll down this street in the company of Max Linder, going firstly south to north on the west side of the street and coming back down the other side, passing in turn numbers 32, 30, 28, 24, 22, 18, 12, 10, 8, 4, 3, 17, 19 and 25:

The street is of great interest also to anyone interested in early twentieth-century French cinema. The direct answer to the question asked in the title of this piece - 'Where is Max?' - is that for a large part of the time Max was on the rue Louis Besquel. The street can be seen in twenty-one of the films I have been able to examine (about sixty), and Max can be seen going into, coming out of or running past at least thirteen of its thirty-two buildings. Several of these buildings appear in more than one film. The gallery below corresponds to a stroll down this street in the company of Max Linder, going firstly south to north on the west side of the street and coming back down the other side, passing in turn numbers 32, 30, 28, 24, 22, 18, 12, 10, 8, 4, 3, 17, 19 and 25:

All of these buildings can be viewed here, photographed in May 2017 by Denis Dupont:

This is not the only local street to be used by Linder. Here he is on the rue des Vignerons and the rue du Bois (now rue Anatole France), streets parallel to the rue Louis Besquel:

And here he is on streets at the top and bottom of the rue Louis Besquel - the rue du Donjon and the avenue des Minimes:

But the rue Louis Besquel remains Max's principal terrain.

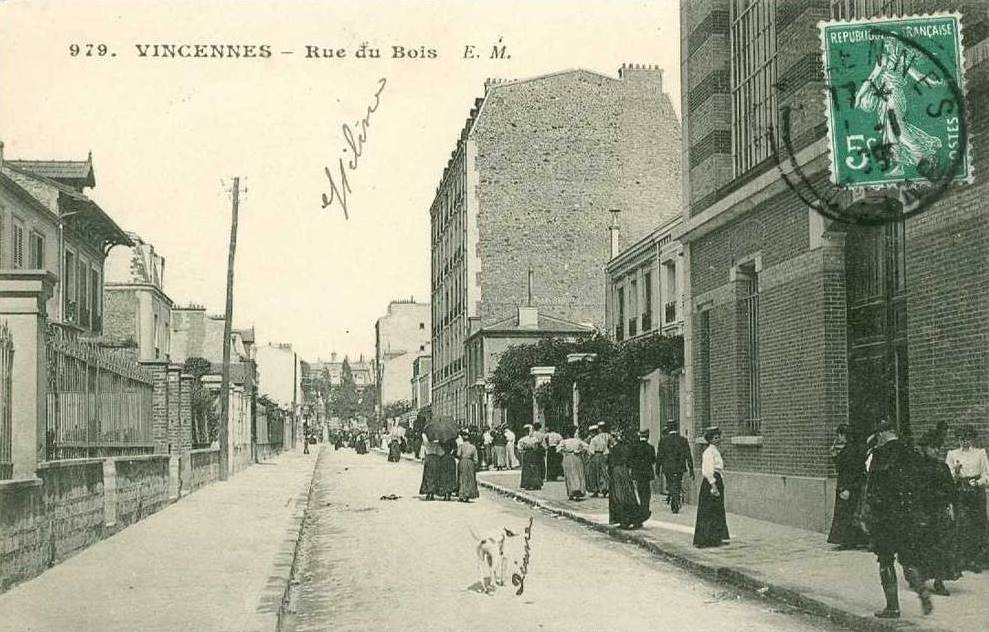

Several factors might explain this preference. One is merely practical. Compared with the rue du Bois and the rue des Vignerons, on both of which were entrances to the Pathé works, this entirely residential street (save for one grocer's shop) would be less encumbered with traffic and pedestrians, including workers coming to or leaving the factory. Compare with the rue du Bois, here:

Several factors might explain this preference. One is merely practical. Compared with the rue du Bois and the rue des Vignerons, on both of which were entrances to the Pathé works, this entirely residential street (save for one grocer's shop) would be less encumbered with traffic and pedestrians, including workers coming to or leaving the factory. Compare with the rue du Bois, here:

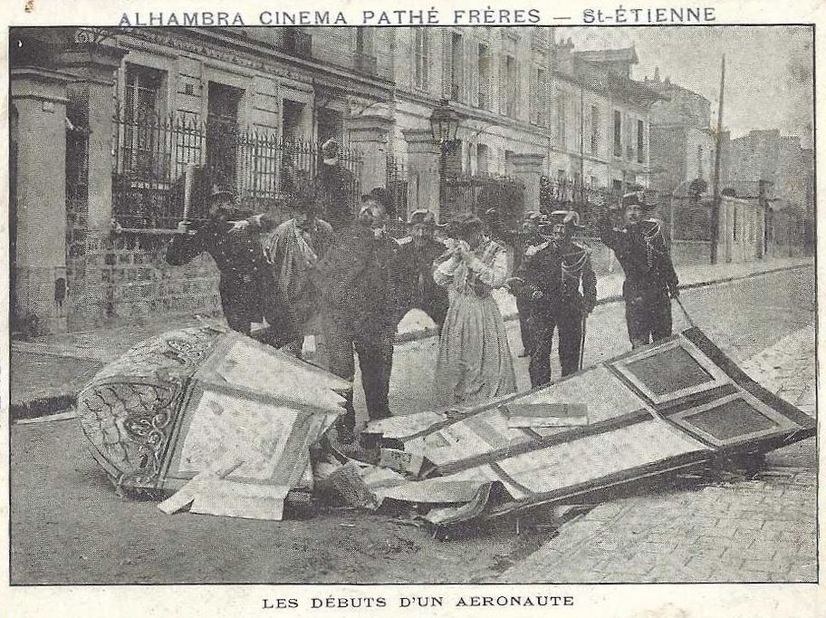

It is true that the rue du Bois could at times be conveniently empty. Here is a publicity postcard for a 1907 Linder film, Les Débuts d'un aeronaute. The card below left illustrates a gag involving a colonne Morris (a pillar for advertising) - Max has just flown past in a hot-air balloon. This was shot just outside the studio entrance we see on the right-hand side of the right-hand postcard above, as was the scene from Le Cheval emballé the same year, below right, which also features the destruction of a colonne Morris:

Another reason why the rue Louis Besquel appears so often in Linder films might be an identification of Max's character with the ethos of this street. Though Max's social status fluctuates a little, he generally conforms to a 'bourgeois rentier' type, or else to someone aspiring to that condition. Here is Richard Abel's description:

|

|

His character is now stabilized into that of an impeccably dressed young bourgeois - in frock coat, tie, and vest, with either striped or black trousers, spats, a top hat and cane. Consistently inhabiting well-appointed apartments, fully equipped with servants, as Sadoul points out, Max rarely ever worked; instead, he either courted young women (not always unmarried), frequented restaurants and nightclubs, or indulged in various sports. In other words, he now epitomized the leisured bourgeois rentier or young man living on an allowance and pursuing a life of "decadence". (The Ciné Comes to Town, p.240)

|

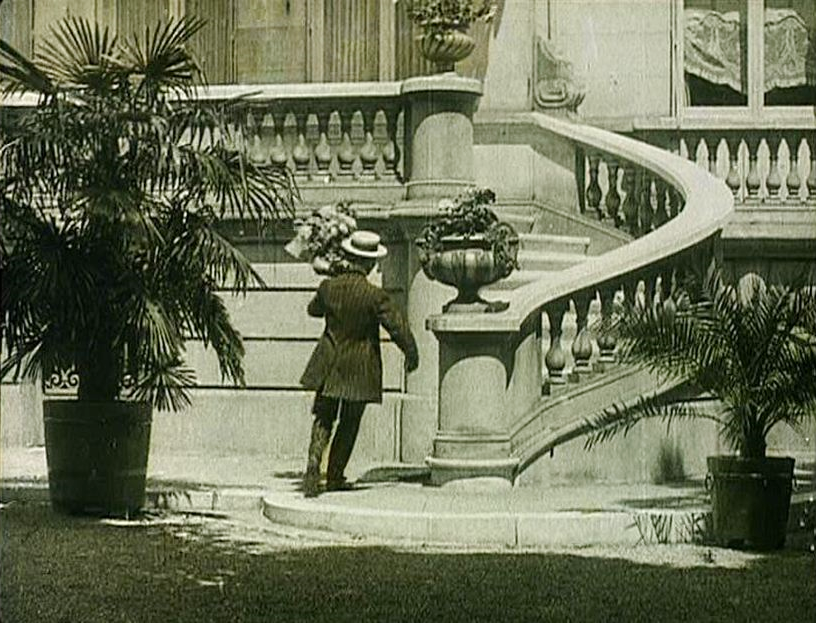

The films make great play from Max's sartorial distinction. Here, in Coiffeur par amour (1914), are three passersby with whom Max wants to change clothes so that he can insinuate himself into the residence behind them:

Patrick Urbain identifies the intended clientele for the variously proportioned residences built by Malo as within the social range Richard Abel ascribes to Max. The elegance, even dandyism by which Max distinguishes himself might then correspond to the visual distinctiveness of Malo's buildings. Max's cinematic persona and Malo's decorative façades both signify a certain modernity, an 'art nouveau' or 'jugendstil'.

A further reason might be, rather, a matter of visual contrast. He occasionally deviates from the elegant sobriety described by Abel - here he is in striped suit and straw boater:

A further reason might be, rather, a matter of visual contrast. He occasionally deviates from the elegant sobriety described by Abel - here he is in striped suit and straw boater:

The excess of Max's ensemble here seems to match the floridity of the setting (Charles Pathé's own home, on the avenue de la Villa):

But Max's definitive image is the svelte silhouette we see here:

The buildings in front of which we discern his elegant outline often seem chosen for the variety and curiosity of their contrasting forms:

By far the most frequent backdrop is one of the most distinctive entrances onto the rue Louis Besquel, at number 32. Here is Max in front of it in six different films:

3/ Vincennes, mise-en-scène

Buildings on other streets around the Pathé works date from the same period as these on the rue Louis Besquel, and even if not all are designed by or under the guidance of Georges Malo, they share an interest in contrasted materials and varying patterns, and serve in similar ways as backdrop when Max finds himself set against them:

These and other streets near the Pathé studios were of course also locations for many films not featuring Max Linder. Denis Dupont's Vincennes 1900 site provides many examples. Here is a small sample, pending an eventual street-by-street mapping of Pathé filmmaking in Vincennes:

The rue Louis Besquel was also of course used by non-Max films, and even if the building at number 32 is Max's defining backdrop, many other filmmakers exploited its distinctive aspect. Here, again, is a small sample:

It does seem strange to me that of the many films shot on the rue Louis Besquel, very few foreground what is by far its most distinctive building, at number 28:

I have seen it in only one film, Bébé victime d'une erreur judiciaire (aka Bébé joue au cinéma), a film that was long thought to be a Feuillade-directed Gaumont production. (See here for an account of why I think it is not by Feuillade, but rather a Pathé production from the time of Bébé's defection from Gaumont.) Even if the vivid colouring of the brickwork escapes us, the roughly hewn blocks of stone attached to the façade as decoration are unmistakable:

I had really hoped to find Max in front of this building. Pending the examination of the 120 or so Max films that I haven't seen, among which several may place him happily in front of Malo's signature piece, I would venture a guess that the outré decoration of number 28 goes too far to serve Linder's purpose. I have argued that other buildings in the vicinity are exploited for their distinctiveness but would add, now, that this is so within limits. The play of forms is one thing, but the backdrop shouldn't be a distraction from the star in front of it.

Remembering also that, although Linder's films are on close examination distinctively Vincennois, a larger audience sees him as Parisian, and his everyday surroundings should not be so outlandish as to counter that impression. In support of this last suggestion, we could look at Max's use of three more buildings in or around the rue Louis Besquel.

At the other end of the street, at number 10, is a doorway that Max goes in or out of in at least six different films:

Remembering also that, although Linder's films are on close examination distinctively Vincennois, a larger audience sees him as Parisian, and his everyday surroundings should not be so outlandish as to counter that impression. In support of this last suggestion, we could look at Max's use of three more buildings in or around the rue Louis Besquel.

At the other end of the street, at number 10, is a doorway that Max goes in or out of in at least six different films:

In none of these six shots do we see anything remarkable about the building that serves as frame or backdrop for the action. The doorway is just functional, especially in the closer framings, when the contrast of brick and stone that distinguishes the façade cannot be seen at all.

An angled shot up the street in Mariage forcé (1914) and another in Coiffeur par amour (1914) do something to display the façade's distinguishing features:

A similar problem presents itself with the next building along, at number 8. Close framing of its doorway would also conceal a contrast of brick and stone:

The doorway at number 8 provides the only instances I have found where we look out from inside a building (the glimpse of Malo's quirky house at number 5 provided the clue for identification here):

Each of these doorways has a surround of stone facing between it and the brickwork, so that, when filmed, close frontal framing makes these buildings look more like buildings of the previous decade. And it makes them look more Parisian, less Vincennois. When it comes to a third commonly used doorway, this impression is all the stronger. The rue Louis Besquel runs into the rue du Donjon, and looks straight onto number 10 of that street:

This building is contemporary with the street it faces, though its brickwork-free ground floor makes it seem stylistically more conventional, especially on camera:

I have looked at the buildings in the vicinity of the rue Louis Besquel that appear in films by Max Linder from the point of view of the buildings, with regret sometimes that certain buildings don't appear, and also sometimes that the camera never looks up to take in the whole building. A case in point is a moment in La Petite Rosse (1909), discussed by Richard Abel (The Ciné Goes to Town, p.238):

|

|

A nifty sequence of substitution follows — alternating between Madeleine at a balcony window and Linder coming out of the street door just below — to sum up her charming manipulation of his inadequacy. As she looks down from the balcony, Linder practices doing a trick with his cane and tosses it overhead. On a matchcut, she grabs it and steps inside; Linder looks around puzzled, suddenly lunges to catch an umbrella she has let fall (unseen), which he lays gently on the sidewalk, and rubs his eyes in disbelief.

|

Here are Madeleine at her balcony and Max in the street:

In case we imagined that, beyond the deftly handled cut, there might be a match of filmic and profilmic reality, we should note that Madeleine's balcony doesn't match the one immediately above Max as he stands on the pavement outside 10 rue Louis Besquel:

Madeleine's window is a studio confection, though the deftness of the cut on her catch makes the transition from street to studio barely noticeable.

When Max is in the street, the camera is at eye level and street level. The buildings behind him had better have a distinctive ground floor exterior, or else they will pass unnoticed. Unlike, for instance, the exterior-centred chase films that sometimes cross paths with Max, the narrative business of Max's films is for the most part conducted in interiors, which are not my concern. What then, in Max's films, is the function of exterior scenes?

Firstly, they can tell us that we have gone from one place to another. Even with the distinctive backdrops provided by Vincennois suburbia in its prime, the streets between interior scenes in Linder films are hard to differentiate, but the studio-confected interiors that they separate are even harder to tell apart. If Max is to be understood to have gone from one place to another, it can be useful to be see him in the street either leaving the first place or arriving at the second. The simplest form this takes is the close frontal or slightly angled shot of a doorway, many examples of which we have already seen:

Firstly, they can tell us that we have gone from one place to another. Even with the distinctive backdrops provided by Vincennois suburbia in its prime, the streets between interior scenes in Linder films are hard to differentiate, but the studio-confected interiors that they separate are even harder to tell apart. If Max is to be understood to have gone from one place to another, it can be useful to be see him in the street either leaving the first place or arriving at the second. The simplest form this takes is the close frontal or slightly angled shot of a doorway, many examples of which we have already seen:

There are occasions, nonetheless, where a film cuts directly from one interior to another, relying on the difference in décor to remind us that we have changed location, as here, in Max pratique tous les sports (1913):

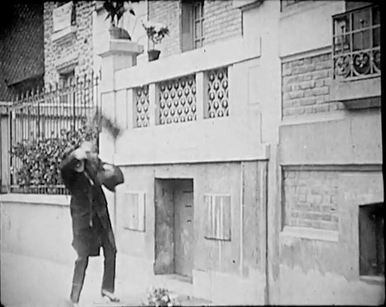

Secondly, exteriors are an occasion for gags. Max is only shown actually on the way from one place to another if something is going to happen to him on the street. In Le Chapeau de Max, he is on the way from the hat shop to the home of his fiancée. At the north end of the rue Louis Besquel he passes a worker who for some reason is holding a door against a fence with his back, and when he bends forward the door falls to flatten Max's hat:

The framing of the first of these incidents is unusually close, the angle unusually wide. This leaves little time for us to see Max coming and anticipate the mishap. The framing of the second incident is the more common, with a camera at a greater distance and the angle more acute, taking in more of the street and allowing us to see Max coming.

If this kind of framing is not used to show an incident, then it is to show an interesting movement of some kind. Running, for example:

If this kind of framing is not used to show an incident, then it is to show an interesting movement of some kind. Running, for example:

Or rolling:

Or crawling:

Or it may be that the camera is so positioned to make the most of an oncoming or departing vehicle:

As we have seen, these angled shots are more likely to give a fuller view of the street, with occasionally, a chance to look up from street level:

Conclusion: Where is Max?

I'd like to finish this piece by looking at where Max is in one particular film, Victime du quinquina, rightly identified by Richard Abel as 'one of the best films of his career'.

There is a reasonably accurate summary of the film, from the journal The Bioscope 04.01.1912, on Georg Renken's Max Linder site. There are several versions of the film available online, though none has a particularly good quality image. The best of them is, I think, here. This is a version that had been shown on Arte. It lasts almost fifteen minutes; a longer version derived from a Pathé Baby re-release is available on YouTube, Daily Motion and at the Internet Archive, but the image quality is worse:

I'd like to finish this piece by looking at where Max is in one particular film, Victime du quinquina, rightly identified by Richard Abel as 'one of the best films of his career'.

There is a reasonably accurate summary of the film, from the journal The Bioscope 04.01.1912, on Georg Renken's Max Linder site. There are several versions of the film available online, though none has a particularly good quality image. The best of them is, I think, here. This is a version that had been shown on Arte. It lasts almost fifteen minutes; a longer version derived from a Pathé Baby re-release is available on YouTube, Daily Motion and at the Internet Archive, but the image quality is worse:

It is slightly perverse to take this film as a case study because although seemingly complete versions are accessible there is some ambiguity regarding a set of intertitles that relate specifically to my question. These intertitles purport to tell the spectator something about where Max is, but what they say may not be reliable.

Briefly: in the course of an evening an inebriated Max offends three dignitaries, receiving a card from each so that he might answer to them in a duel. Later, Max is found drunk in the street on three occasions by three different policemen, to each of whom he gives not his own card but one of those he received earlier that evening. As a consequence he is taken by each of the policemen to be someone eminent, and each takes him to the address on the card he gives them (the consequence being that he is confronted with each of the persons he had offended earlier that evening).

Briefly: in the course of an evening an inebriated Max offends three dignitaries, receiving a card from each so that he might answer to them in a duel. Later, Max is found drunk in the street on three occasions by three different policemen, to each of whom he gives not his own card but one of those he received earlier that evening. As a consequence he is taken by each of the policemen to be someone eminent, and each takes him to the address on the card he gives them (the consequence being that he is confronted with each of the persons he had offended earlier that evening).

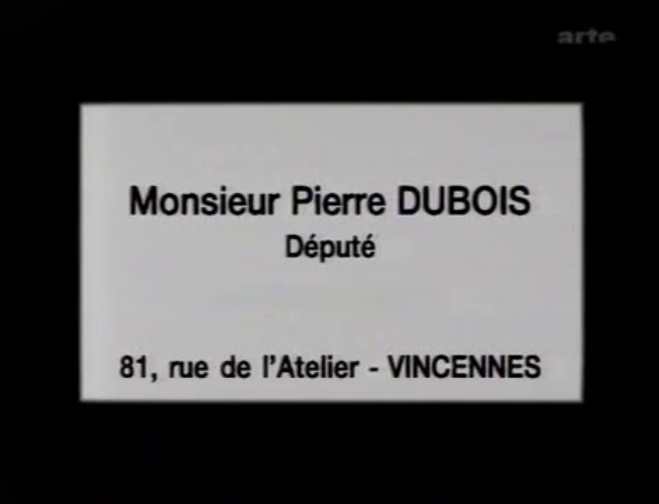

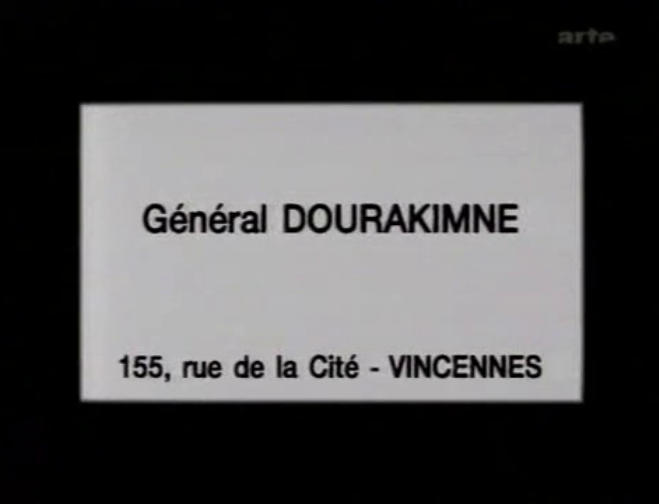

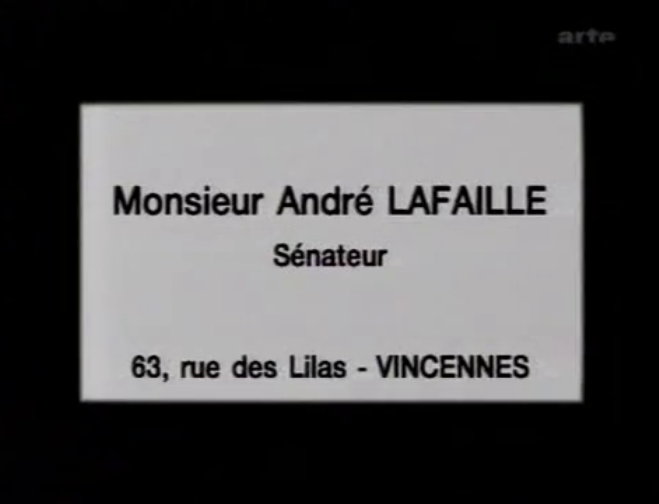

In the Arte version , the cards Max receives and then redistributes read as follows:

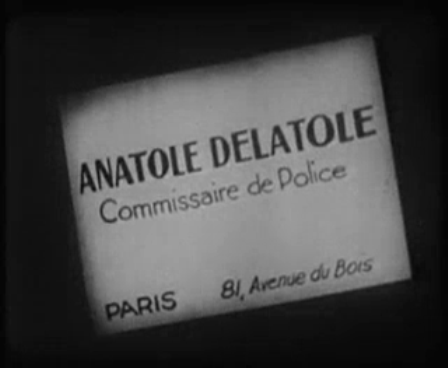

In the Pathé Baby version of the film, the names and addresses are very different:

If all else were equal I'd prefer the first set of addresses, since I'd be glad to locate Max in Vincennes not just physically but also narratively. However, the inserts giving the first set of addresses are clearly modern confections and do not seem textually authentic. Whoever confected them wanted (like me) Max to be in Vincennes, but didn't want him to be located too precisely, since none of those streets actually exists, or ever existed, in Vincennes. This person did match the addresses on the cards to the street numbers we see in the film, but then so did the person who wrote the second set of cards. The latter wanted Max to be in Paris and, by giving all three an address on the 'Avenue du Bois' ('...de Boulogne', I assume again, as with Max pratique tous les sports), was more faithful to the film, since at its denouement all three policemen come together on the street and point to different parts of it as the address at which Max belongs.

The second set of addresses has on its side the fact that the functions of the three dignitaries correspond to those of contemporary descriptions of the film (see here and here), and also the aspect of of the inserts, which are clearly not modern.

But I am not entirely convinced. Though the Pathé catalogue description gives no addresses, it has quite different names for the dignitaries: 'La Roze, Commissaire de Police'; 'Le marquis Cachtapinto del Salvator, ministre plénipotentiaire'; 'le Général Jean Nesoupey'. These could have been original suggestions that were abandoned but then still found their way into the catalogue description, certainly. It could also be that the second set of cards are a later invention, from the moment when Max's films were being repackaged for the home cinema, 'Pathé Baby' market in the early 1920s. In support of this contention, we should note that in this version the first man Max encounters gives him the card that reads 'Placide Trafalgar':

But I am not entirely convinced. Though the Pathé catalogue description gives no addresses, it has quite different names for the dignitaries: 'La Roze, Commissaire de Police'; 'Le marquis Cachtapinto del Salvator, ministre plénipotentiaire'; 'le Général Jean Nesoupey'. These could have been original suggestions that were abandoned but then still found their way into the catalogue description, certainly. It could also be that the second set of cards are a later invention, from the moment when Max's films were being repackaged for the home cinema, 'Pathé Baby' market in the early 1920s. In support of this contention, we should note that in this version the first man Max encounters gives him the card that reads 'Placide Trafalgar':

This is the first man Max is brought to later that evening by a policeman, but the card Max had given that policeman was that of 'Anatole Delatole' ('Commissaire de Police, Paris, 81, Avenue du Bois'). He had indeed been brought to a house numbered 81, so the first insert of a card (reading 'Placide Trafalgar') was the wrong insert. I'd say that such a mistake is more likely to have happened in a re-editing of the film than in the original.

This is not to say that the Arte version is the original, or even a more authentic version. The modern aspect of its card-inserts is problematic, as also is the fact that it is lacking an important part of a key scene that is present in the Pathé Baby version. When Max is taken by the second policeman to the second person's address, no. 155, the Pathé Baby version shows Max entering an empty room, looking queasy and then vomiting into a hat. The occupier then enters, which is where the scene in the Arte version begins. When this man brings weapons for their duel, Max runs the rapier through his own hat while his adversary puts on his, covering himself in Max's vomit as a consequence:

None of this business is in the Arte version. Clearly the gag was thought too revolting and removed, hence the intertitle that appears in the middle of the sequence, avoiding a jumpcut at the point of excision.

My conclusion, then, is that the two versions are both defective in some way. Nonetheless I shall pursue my inquiry and even with deficient evidence try to answer my question: 'Where is Max?', through an examination of the film's spaces and places.

Counting the street-level doorways as exteriors, there are nine interiors spaces in this film, at least according to the narrative.

The consulting room and Max's home are unremarkable interiors. The restaurant makes good use of the back-, middle- and foreground to demarcate types of activity:

The consulting room and Max's home are unremarkable interiors. The restaurant makes good use of the back-, middle- and foreground to demarcate types of activity:

The apartments of Max's three opponents are carefully differentiated by the type of room we are shown. We see the Chief of Police in a small dining room, the Ambassador in a more spacious salon, and the Minister of War in the bedroom:

The three landings at the top of staircases leading to the apartments are differentiated narratively but visually the differences are minimal. The third is exactly the same as the first, except that a sofa has been removed. The second is the same as the other two, except that it is framed more closely:

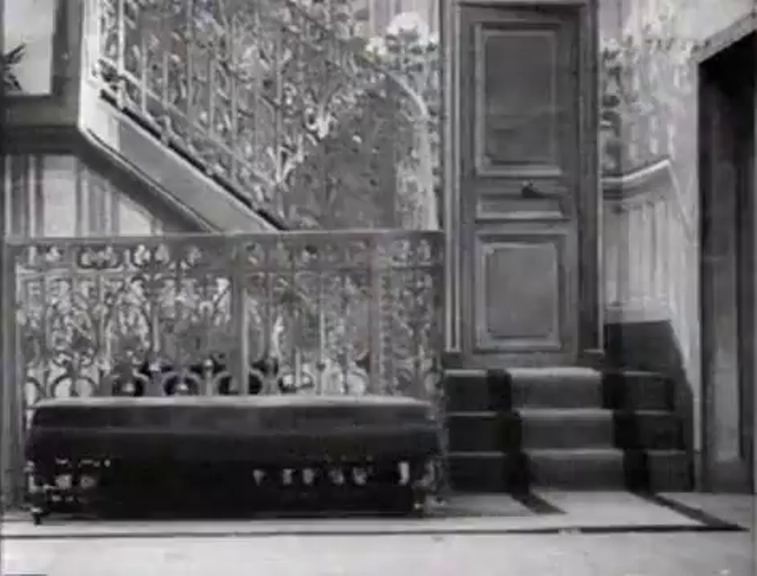

This suggests an effort at economy, but that doesn't explain the anomalous appearance of a completely different landing. When Max is kicked out of the first apartment, the landing we see is not the one that had previously been outside this apartment. There is no sofa, the banisters are different, there are four steps leading up to the door at the back, not three, and that door itself is different:

This anomaly is matched by the doorways that open and close this sequence. The doorway through which Max is carried in by the policeman is not the same one by which he exits when ejected by the Chief of Police:

The recurrence of the same studio-built staircases in Pathé films is notorious (see Barry Salt, 'The Pathé Staircase', in Film Style and Technology, p.51). Here are the two layouts we see in Victime du quinquina as they appear in Max ne se mariera pas and Max prend un bain:

I have insisted on the detail of the landings in Victime du quinquina because doorways in Linder films are a functional equivalent, and it is only because there were real ones conveniently nearby that there isn't the same recurrence of the same studio-built doorways in Pathé films. The recurrence of real doorways I have already discussed, but I shall have to come back to them in a moment.

There are nine exteriors in Victime du quinquina. The first shows the street near Max's home where he argues with the Chief of Police over a cab:

There are nine exteriors in Victime du quinquina. The first shows the street near Max's home where he argues with the Chief of Police over a cab:

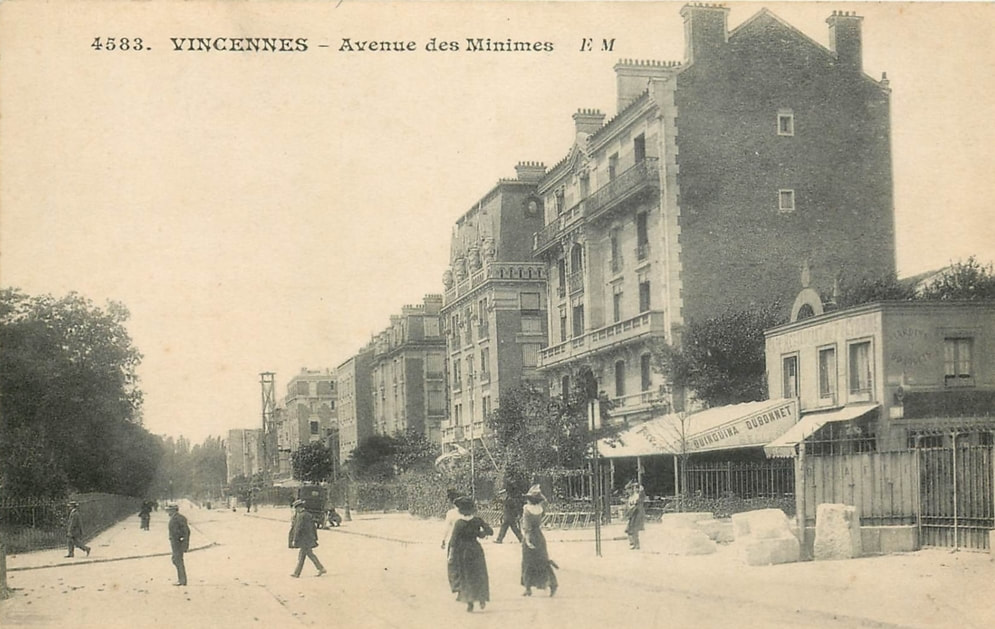

They are standing on the corner of the rue Louis Besquel and the avenue des Minimes. Here is a different view of the house behind the Chief of Police, from Le Cheval emballé:

The café we can see above is just offscreen in Victime du quinquina. Had it been visible, and shot from the other direction, perhaps we would have seen the advertisement for 'Quinquina Dubonnet' on its awning, as in this postcard:

We next see Max much later in the evening, trying to find his way home. He is on the corner of the avenue du Polygone and the avenue de la Villa, at the top of the street that turns right just after the café in the postcard above. From here he is carried to 10 rue Louis Besquel ('no. 81'):

When he is thrown out of this building he rolls out of a doorway at the other end of the street, at number 32, then rolls half way up the street, wrapped in a tablecloth, and bumps into a policeman in front of number 18:

This second policeman takes him to 10 rue du Donjon ('no 155'). He is thrown out of a window of this building, only to land on a third policeman walking past 10 rue Louis Besquel (the building to which he had been taken by the first policeman):

The third policeman carries him next door, to 8 rue Louis Besquel ('no 63'). Max is ejected twice from this address. The first time he is kicked out via the apartment door, and Max staggers out of the building of his own accord. This is the only time that Max comes out of the same building that he has entered, though this time, unfathomably, the number of the building has been changed from '63' to '81':

The third policeman come across him again, and brings him back into the building and up to the Minister's apartment. Max is ejected a second time, this time via the window, and this time he lands on all three policemen, who had gathered for a chat outside a building two doors down, number 12:

Each policeman recognises the gentleman he had earlier helped home, and each insists that the gentleman's home is in a different part of the street. They take out the different cards they had been given by Max, consider that they have been duped, and proceed to beat him up (in front of one of Georges Malo's ornamental façades). There the film ends.

The topographical inconsistency regarding where Max is in the street does not seem to me to be of the same order as the inconsistency re. the landing outside the first apartment, even if for most audiences both might pass unnoticed. The fact that Max consistently leaves a different building from the one he entered looks like elaborate play. Perhaps it is play only for the benefit of the locals, or even only for those locals directly involved in filmmaking at Pathé (several of whom lodged in houses on the rue Louis Besquel and the rue du Donjon - see Pathé: premier empire du cinéma, p.139).

The topographical inconsistency regarding where Max is in the street does not seem to me to be of the same order as the inconsistency re. the landing outside the first apartment, even if for most audiences both might pass unnoticed. The fact that Max consistently leaves a different building from the one he entered looks like elaborate play. Perhaps it is play only for the benefit of the locals, or even only for those locals directly involved in filmmaking at Pathé (several of whom lodged in houses on the rue Louis Besquel and the rue du Donjon - see Pathé: premier empire du cinéma, p.139).

Perhaps the play signifies something more, a way of matching the conflation of architectural forms to Max's ambiguous social position. For the policemen, Max easily passes as the Chief of Police, an ambassador or a government minister, and in the apartment of each he is entirely at home. Each dignitary considers him sufficiently his equal to duel with him, and it is only the beating he receives from the policemen that suggests that Max does not occupy the place in society they had thought (though how do they know he is not still someone eminent?).

Building on Richard Abel's observations, Vicki Callahan has discussed at length Max's 'uncertain class identity' ('Mutability and Fixity in Early French Cinema', pp.68-9):

Building on Richard Abel's observations, Vicki Callahan has discussed at length Max's 'uncertain class identity' ('Mutability and Fixity in Early French Cinema', pp.68-9):

|

|

While Linder appears to correspond to an established social type - looking like an impeccably groomed member of the bourgeoisie - his status is always uncertain and shifting before our eyes. Thus Richard Abel argues that Linder's early film persona seems to fit the somewhat blurred social category of the rentier, a person of independent means, or in Max's case “a lower class bourgeois figure with pretensions to that status”.

[...] The vagueness and elasticity of Max's status makes him typically proto-modern and aspirational. What the character comically shows us is that the best start towards social advancement is the correct look and the proper accessories of the lifestyle. Thus, even by 1910, when Max appears more solidly outfitted in the trappings of bourgeois society (complete with servants and infinite leisure time), we are still not sure if this is due to good lineage or merely to good taste. [Callahan goes on to discuss Victime du quinquina] The comic narrative concerns the true site of identity and respectability for a Frenchman in the Third Republic: the printed calling card. Here, a series of policemen misidentify a drunken Max and try to return him to his home address. Each policeman takes him to an address found on the numerous calling cards that he has, in fact, picked up on his drunken spree (the cards were given as reminders of his appointments to various duels the next morning). The cards, in conjunction with his dress (if not his behaviour), signify a gentleman, and thus, rather than spending a night in jail, Max is delivered to a succession of respectable homes (and in one instance he is even returned to a respectable wife in bed). Alongside their purely comic motivations, the narrative and performative strategies of Max Linder films play out important cultural anxieties about changing social status and structures. |

I would add that Max's social persona isn't just a vague mix of representations ( gentleman, rentier, parvenu, dandy, marginal...), it is also a specific construction, deliberately elastic, but not vague. Whether or not a film directly represents him as someone who makes films (as in Les Débuts de Max au cinématographe and Mari jaloux), Max's screen persona is always that of Max the film performer. His mutability enables him to assume roles in order to seduce (juggler, artist, musician, hairdresser, pedicurist, butler, jockey, boxer, bandit...), and to take a beating in order to raise a laugh, but beyond the premises of narrative and spectacle, this mutability is, through play, a performative deconstruction of fixed social status and structures. It is, as such, a synecdoche of the cinema in 1911: elastic, socially mobile, and (as Callahan says of Max) 'with enough income to avoid work'. (Like Bébé, 'Max joue au cinéma', because the cinema is play.)

We never see the calling card that Max gives to his adversaries in return for theirs, so we don't know what occupation it would have ascribed to him. To say 'artiste cinématographique' may to be pin him down too easily, allowing him to be despised by the dignitaries he encounters. I'd guess it would just have written on it 'Max', and his address, which would be no less respectable an address than theirs. (He probably does live on the same street as them.)

We never see the calling card that Max gives to his adversaries in return for theirs, so we don't know what occupation it would have ascribed to him. To say 'artiste cinématographique' may to be pin him down too easily, allowing him to be despised by the dignitaries he encounters. I'd guess it would just have written on it 'Max', and his address, which would be no less respectable an address than theirs. (He probably does live on the same street as them.)

So where is Max?

Socially, like the cinema, he is on the move: proto-modern and aspirational, upwardly mobile, with pretentions to respectability. As Ginette Vincendeau puts it: 'Linder can be located at the intersection of two different histories: that of the (international) film industry's growing embourgeoisement (its move out of the fairground and bid for middle-class respectability and audiences) and a specific French theatrical tradition' ('Max Linder', p.47).

Geographically, as this piece has sought to illustrate, Max is mainly in Vincennes, because that's where the cinema, i.e. Pathé, is.

Here, to close, is Max at the end of Les Débuts de Max au cinématographe, on the rue du Bois, just outside the entrance to the Pathé studio. He is being directed to blow kisses at the camera:

Socially, like the cinema, he is on the move: proto-modern and aspirational, upwardly mobile, with pretentions to respectability. As Ginette Vincendeau puts it: 'Linder can be located at the intersection of two different histories: that of the (international) film industry's growing embourgeoisement (its move out of the fairground and bid for middle-class respectability and audiences) and a specific French theatrical tradition' ('Max Linder', p.47).

Geographically, as this piece has sought to illustrate, Max is mainly in Vincennes, because that's where the cinema, i.e. Pathé, is.

Here, to close, is Max at the end of Les Débuts de Max au cinématographe, on the rue du Bois, just outside the entrance to the Pathé studio. He is being directed to blow kisses at the camera:

references and sources

- Vincennes au cinema en 1900

- La filmographie Pathé (Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé)

- Max Linder (Georg Renken)

- Max Linder films at the Internet Archive

- Richard Abel, The Ciné Goes to Town: French Cinema 1896-1914 (Berkeley: University of Califirnia Press, 1998)

- Vicki Callahan, 'Mutability and Fixity in Early French Cinema', in Michael Temple & Michael Witt (eds), The French Cinema Book (London: BFI, 2004)

- Laurent Mannoni, 'Les studios Pathé de la région parisienne (1896-1914)', in Michel Marie & Laurent Le Forestier (eds), La Firme Pathé frères 1896-1914 (Paris: AFRHC, 2004)

- Jacques Kermabon (ed.), Pathé: premier empire du cinéma (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1994)

- Ginette Vincendeau, 'Max Linder: the world's first film star', in Stars and Stardom in French Cinema (London: Continuum, 2000)

- The postcards used as illustrations were found on collector sites such as CPArama and delcampe.net