|

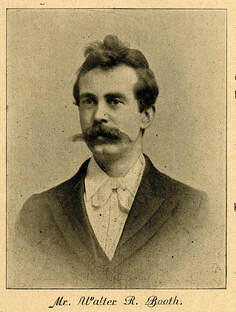

Walter Booth in Muswell Hill This is a post about the roughly seven years Walter Robert Booth spent working on films for Robert Paul at his Muswell Hill premises. For overviews of his career see the entry in the Who's Who of Victorian Cinema (here), Luke McKernan's blogpost 'A Movie Magician' (here) and Malcolm Cook's article 'The lightning cartoon: Animation from music hall to cinema' (here). 1/ 1897-1899 In her 2016 thesis on the film exhibitor William Slade, Patricia Cook notes that Walter Booth worked with Slade between March and July 1897, in Worcester, Cheltenham, Exeter and other towns. She gives a succinct account of the rôle played by Booth in these exhibitions: |

|

|

Slade recognised the benefit of having a professional entertainer, and engaged Walter Booth as a ventriloquist and lightning sketch artist. Having Booth to complement the film programme with his marvellous range of skills and an ability to engage an audience would have provided that extra element which the film shows, vulnerable to technical problems, needed. By advertising Booth as providing 'refined drawing room entertainment', Slade was careful to avoid any association with the music hall, emphasisisng that the show was arranged to meet the tastes of a middle-class audience. (Cook 2016 p.112)

|

|

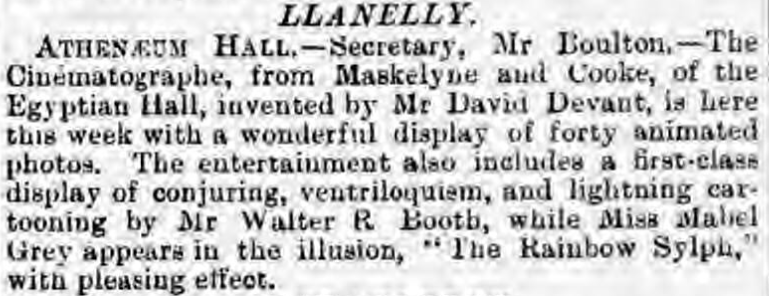

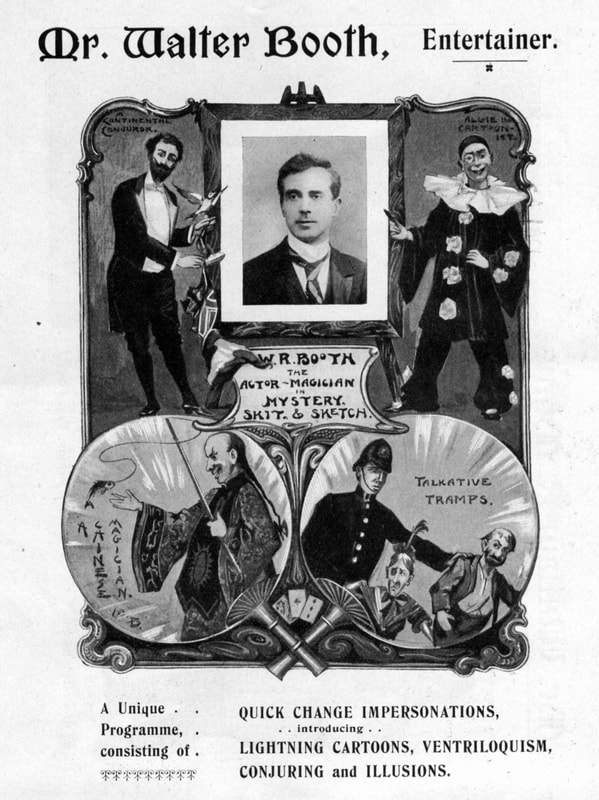

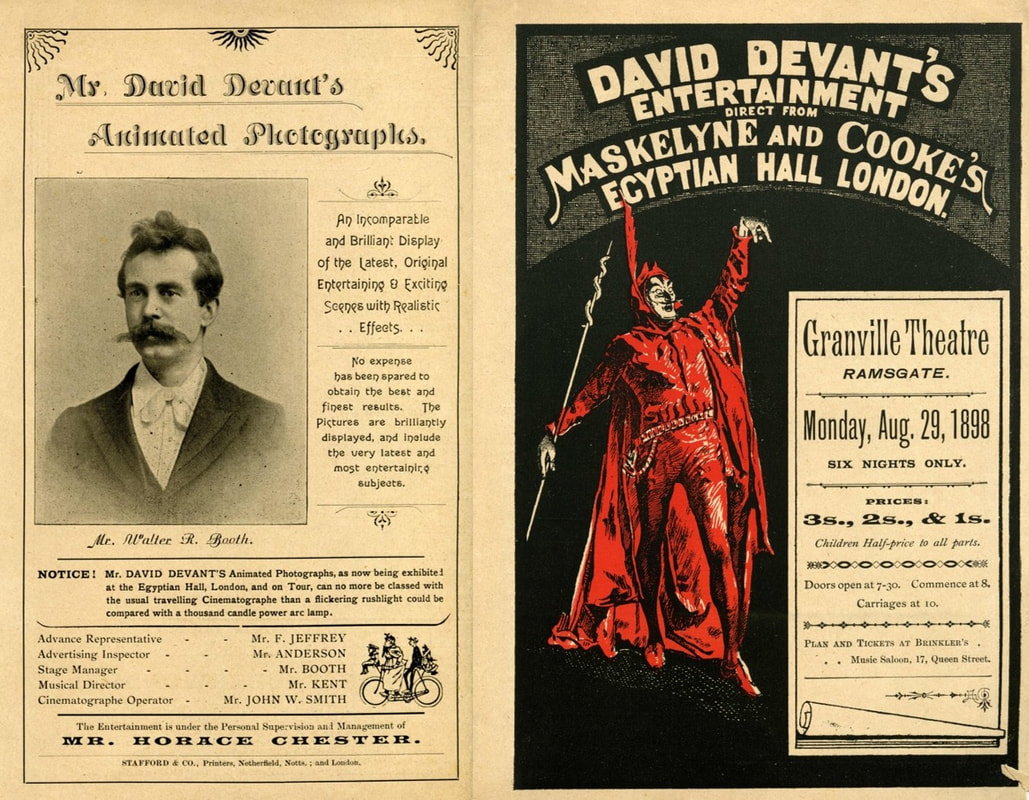

By the end of 1897 was performing as part of David Devant's touring show for Maskelyne and Cooke, where there was less need to emphasise the refinement of his act. The components thereof included conjuring tricks, lightning cartooning, ventriloquial sketches, sleight-of-hand and mind-reading.

|

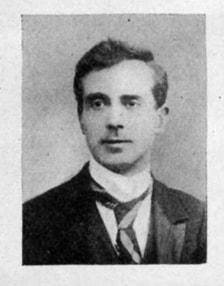

In the Davenport Collection, a wonderful resource for researchers into 'magic and entertainment history', are two brochures, published for Maskelyne and Cooke, that show Booth to have been an established and valued part of the Devant show:

As with Slade, the show included 'animated photographs', but the films this time were provided by Robert Paul, Booth's eventual employer. Booth continued with the Devant show until the end of 1899 though by October 1899 he was also working for Paul.

2/ Walter Booth on screen, 1899-1906

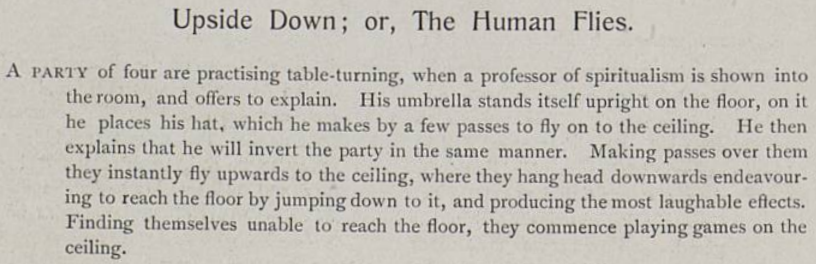

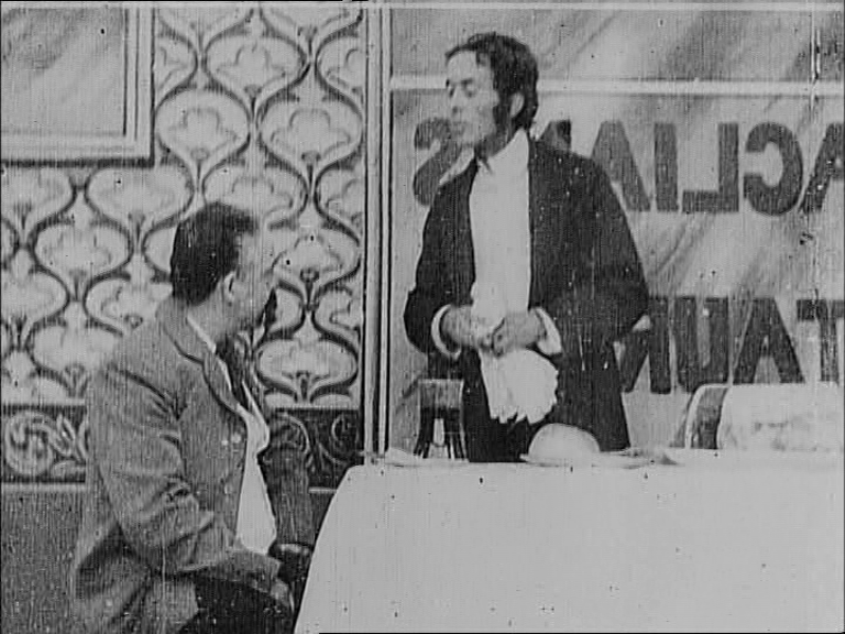

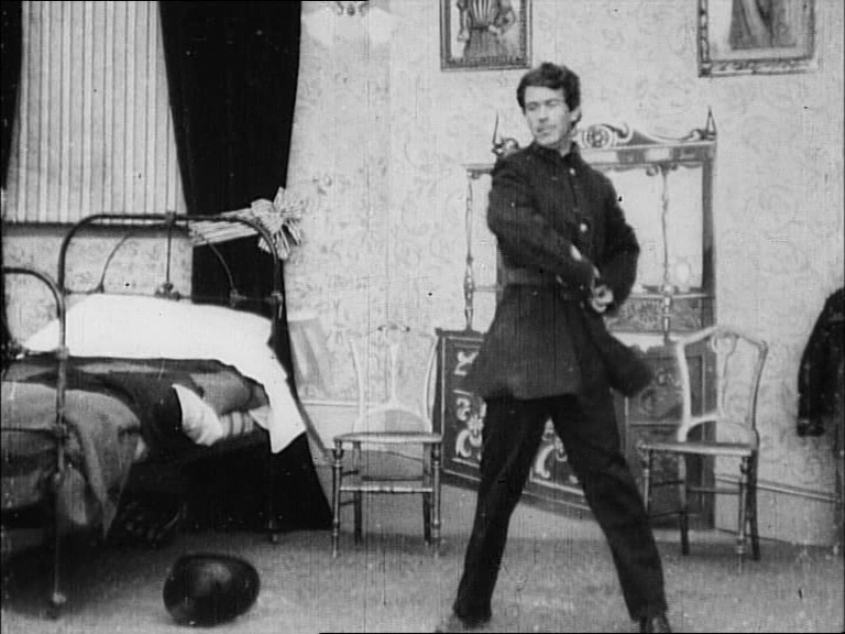

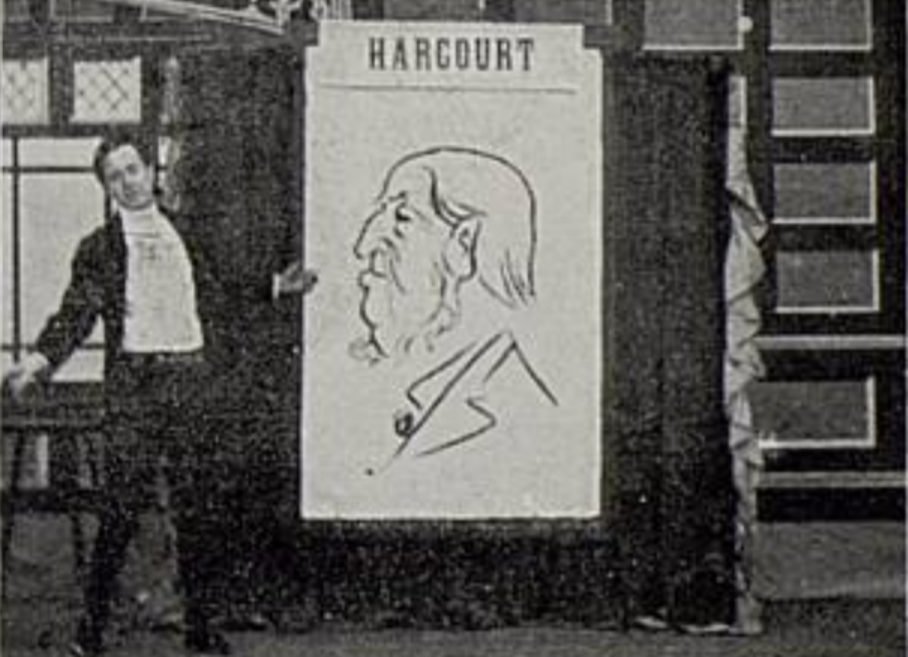

Upside Down is a remarkable trick film that demonstrates sophistication in both staging and editing. Paul had already mastered the necessary skills to achieve this, but the idea of combining cinematic trickery with the trickery of the stage may have been prompted by the arrival of Booth. The professor of spiritualism's first acts are basic conjuring, one of Booth's professional selling points, but the subsequent illusions, making himself disappear and turning his audience upside down, are not. Booth's contribution to the film is his stage presence, the quality that had made him appreciated by Slade and, presumably, Devant. That same presence, adapted to the exigencies of the screen, put him at the centre of several Paul productions in the following six years, some but not all thematically associated with his experience on the stage. Booth can be identified as a performer in at least 9 films: Upside Down, as a magician (1899), His Brave Defender, as a concerned neighbour (1900), The Cheese Mites, as a waiter (1901), The Over-Incubated Baby, as a 'doctor's boy' (1901), Undressing Extraordinary, as a weary traveller trying to get undressed for bed (1901), The Waif and the Wizard, as a conjurer (1901), Artistic Creation, as a lightning sketch artist, himself effectively (1901), Political Favourites (1904, a lost film), as a lightning sketch artist, himself again, and A Lively Quarter-Day, as a conjuror with magic powers (1906).

|

Robert Paul's 1907 catalogue has an image from The Freak Barber (1905) where the barber could well be Booth, but the image is not clear enough to be certain.

In a highly important contribution to Booth studies, given at the 2016 Pordenone festival, William Barnes also came up with a figure of nine (see below right), but he may not have meant the same films. |

I am also surprised by Barnes's description of Booth in Undressing Extraordinary as 'uncharacteristically whiskerless'. One of the most striking things about Booth on screen is his frequent whiskerlessness. I would guess that, as a Quick Change Impersonator, the option of adding or removing facial hair was essential.

3/ Booth as filmmaker

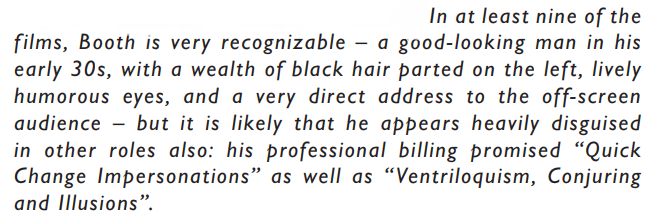

The importance of William Barnes's intervention at Pordenone does not lie in his views on Walter Booth's facial hair but in his eloquent insistence that the attribution of films produced by Paul between 1899 and 1906 to Walter Booth is a serious error in need of correction. This is Barnes's text from the Pordenone catalogue (2016. pp. 207-08):

In his indispensible monograph on Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema (2019, pp.245-46), Ian Christie restates the case conclusively:

Despite this consensus of the wise, it doesn't seem likely that the profligate attribution of Paul-produced films to Walter Booth as director will be redressed, so ingrained is the idea in the internet and in the minds unthinking auteurists.

4/ The Booths in Muswell Hill

|

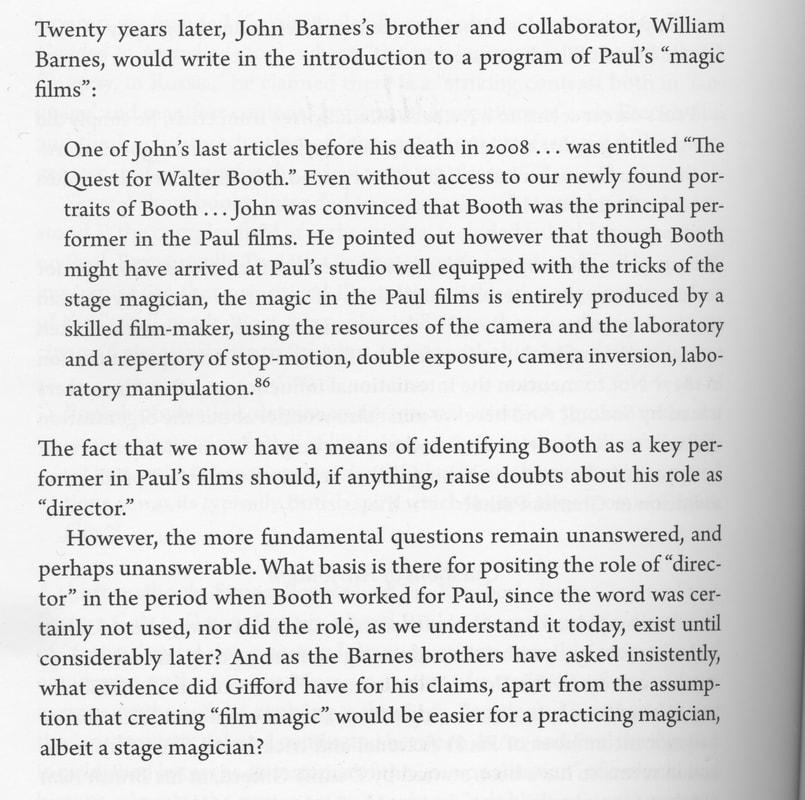

Some time between April and May 1900, Walter Robert Booth married Sarah Grace Roberts at King's Norton, Worcestershire (near Birmingham). Sarah was three years younger than Walter. By March 1901, when the Census was taken, they were living as lodgers at 'Ferndale', 22 Greenham Road, N.10. This newly built house was walking distance from where Booth was employed:

|

The square encloses the studio and film works; the marker on Colney Hatch Lane marks the house which Robert Paul occupied in 1903, at no. 57; the marker on Barnard Hill (no. 10, 'Gardena') is the home of J. H. Martin, who worked for Paul until 1908, when he left to form a partnership with G.H. Cricks. Cricks also worked for Paul c. 1900, but he did not live locally.

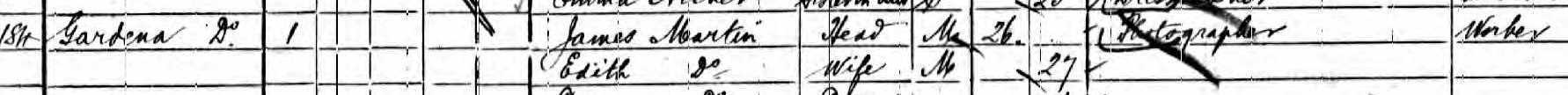

In a manifesto-like advertisement of October 1898, Paul had announced that 'during the past Summer a Staff of Artists and Photographers have been at work in the North of London with the object of Producing a series of Animated Photographs (eighty in number) [...]. These Eighty Films, which have been produced regardless of expense, with specially made Dresses and Backgrounds, are now ready for issue'. James Martin (not John, as he is sometimes called) was probably a part of that initial staff, and perhaps so was Booth. In the 1901 Census Martin gives his profession as 'photographer':

How, then, in the same census, does Walter Booth describe himself - Conjurer, Ventriloquist, Lightning Cartoonist, Quick Change Impersonator, Illusionist, Thought Reader?

None of those. He describes himself, rather, as a Scenic Artist, working for his own account, i.e. self-employed (Martin, as an employee of Paul, had put 'worker'). I have a sense that Booth's situation was more precarious than might have been supposed.

|

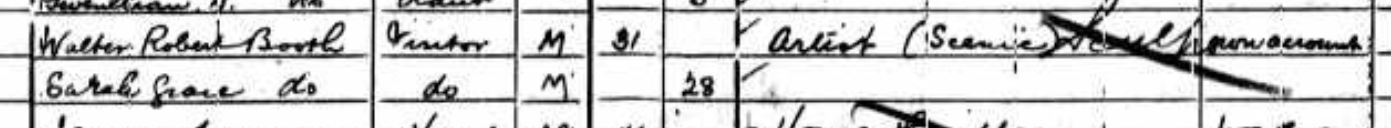

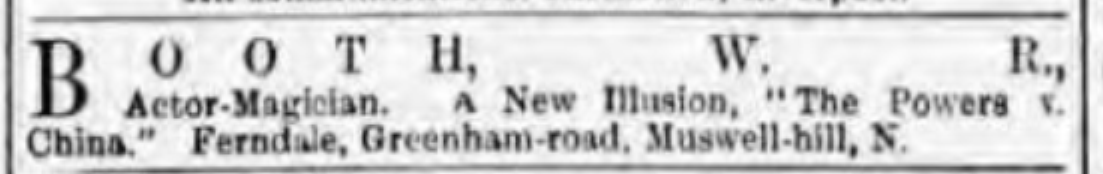

In August and September 1900, when already appearing in films for Paul, Booth was advertising for stage work as 'Actor-Magician', promising a new illusion called 'The Powers v. China'. In fact Booth continued to appear as a stage performer around the country, often on his own account, till at least 1903. He also did so as an employee of Robert Paul, accompanying screenings of Paul's series Army Life; or, How soldiers are made (1900). We can see from this review (right), from the Portsmouth Evening News (01.01.1901), that Booth did get to present his China-themed illusion.

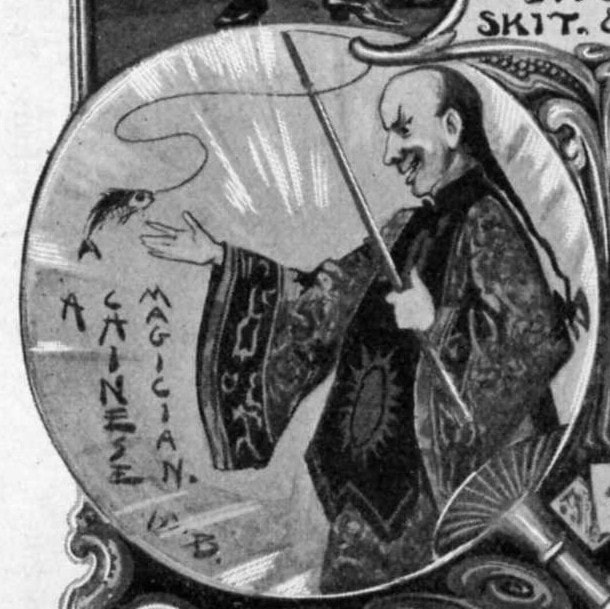

One of the publicity brochures produced by Maskelyne and Cooke shows Booth as a Chinese magician, and given this predilection I think it reasonable to suggest that he is the performer in Paul's lost film Chinese Magic, aka Yellow Peril (1900): |

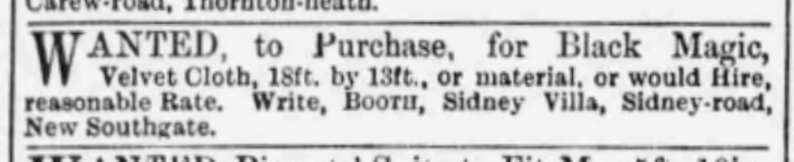

Booth worked for Paul as an actor in films and as live entertainment in the intervals of screenings, but we must suppose that he did at some point work as a scenic artist. One piece of evidence suggests that he did, among other things, work on set design for Paul's films. He placed this advertisement in The Era in May 1900:

I don't think Booth was actually intending to practise black magic, but I don't think either that he wanted this cloth for use in a stage appearance - it would have been much too heavy to bring along to venues. Much more likely is that it was meant as a backdrop for animated photographs. Confirmation of this isn't likely to come from the films themselves, of which several are played out against a black, possibly velvet background; moreover, hiring the cloth suggests that it is wanted for a specific project. The advertisement is an intriguing dead end.

The address Booth gives is that of a house near the film works; in 1898 Paul is listed in Kelly's Directory as living there, though his main residence was on High Holborn, opposite his business premises.

The address Booth gives is that of a house near the film works; in 1898 Paul is listed in Kelly's Directory as living there, though his main residence was on High Holborn, opposite his business premises.

5/ A Family Portrait

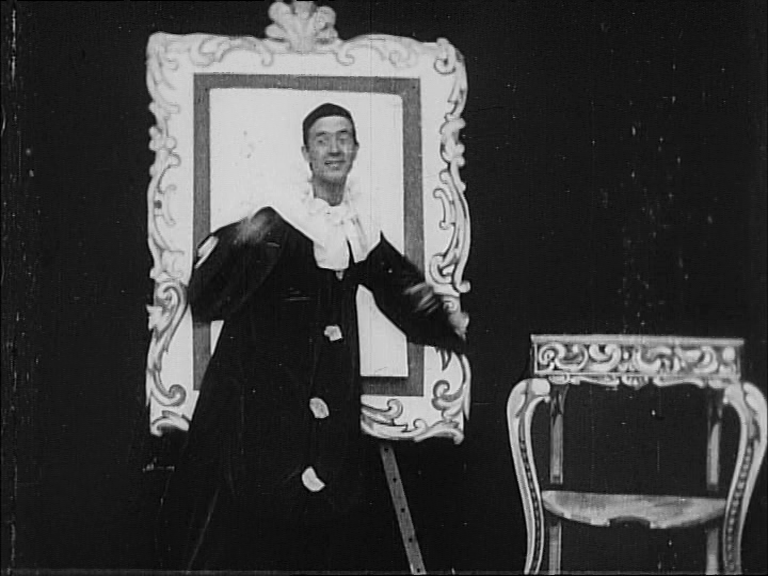

Of the films Booth would have been involved with in his time with Robert Paul, several related directly to his experience as a stage performer, most directly with those that exhibited his skills as lightning sketch artist. Of these, Artistic Creation (1901) survives in excellent condition, and I fully agree with the summary in Paul's catalogue: 'This is considered the finest and smartest picture of the kind ever taken, and a perfect photograph.'

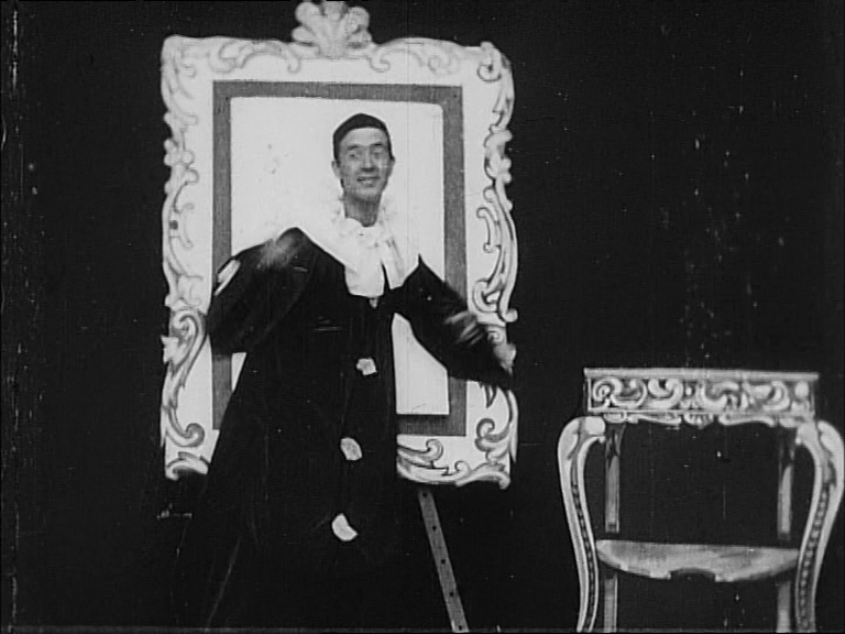

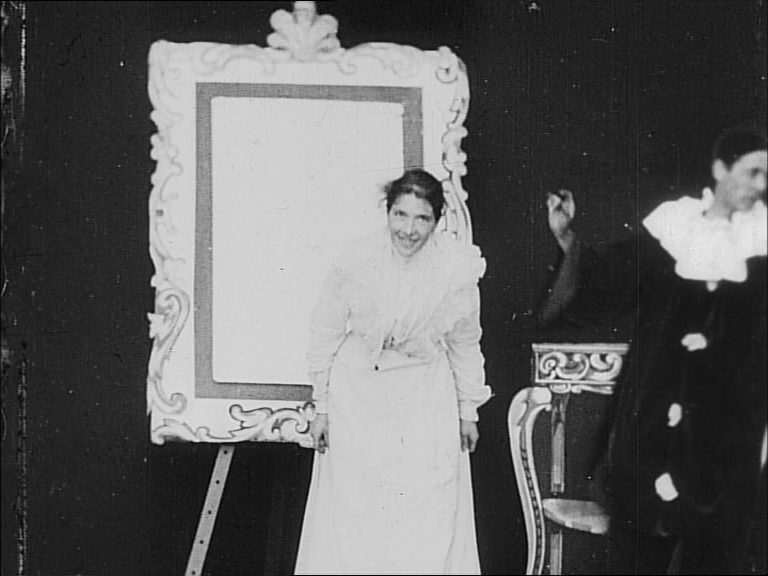

The film relies on cinematic not stage effects, though the staging probably corresponds well enough to what the staging of Booth's act looked like, an easel with paper to draw on and a table for props. Booth goes further, wearing for the film exactly the same Pierrot outfit he wore as 'Algy the Cartoonist' in the Devant show two or three years earlier:

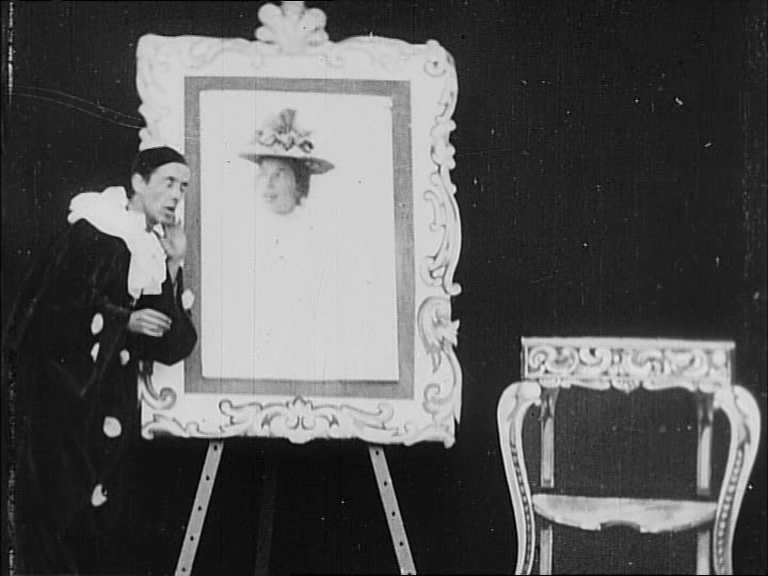

The cartoonist draws a woman's head, which then becomes a real woman's head which he places on the table. He then draws a torso which he places under the head. The woman asks for arms and then a lower half, making her whole. She takes a smiling bow and he invites her to sit down, because he has one last thing to draw:

He starts drawing a baby but she immediate runs off screen in horror. When he turns and finds her gone, in consternation he brings the baby towards the camera and the film ends with a remarkable view of Booth and baby:

Remarkable too is the performance of the woman assembled by the cartoonist. Her demeanour is unusually natural and relaxed, both in her exchanges with Booth and in her address to the audience. There is a moment just after she is made a complete woman where they switch sides of the stage and their gestures suggest an uncommon familiarity. I do not think this an actress, I think this is Sarah Grace Booth, helping out her husband in the execution of 'his 'artistic creations'.

What further persuades me that this is husband and wife is that on June 14th 1901 Sarah gave birth to a son, Sydney Robert Booth. The baby in the film is not a doll or a bundle of rags; it is clearly young Sydney, who would have been about three months or so when the film was made. When Booth brings the baby towards us there is at the end an evident tenderness towards the child, when in any other film of that moment - see The Over-Incubated Baby (1901) - the child, even if not a doll, is merely a prop.

Artistic Creation is a personal film, but it also a sophisticated illustration of creation at various levels. The cartoonist is a creator of images whose powers are increased by cinematic device, allowing him to create living beings from his drawings.

Artistic Creation is a personal film, but it also a sophisticated illustration of creation at various levels. The cartoonist is a creator of images whose powers are increased by cinematic device, allowing him to create living beings from his drawings.

|

Can we say that Artistic Creation is 'a Walter Booth film'? He and his family are the actors, the props and costume come from his stage work, the idea for the film may well have been his, but there would be others involved in its making. Someone determined that the action should be staged as close to the camera as possible, and that there would be no distractions in the background, just a black (velvet?) backdrop. (Compare with the staging of Political Favourites (1904), right.) |

A photographer operated the camera, and a highly skilled editor made the numerous substitution cuts pass smoothly. It is meaningless to call any one of the individuals involved the director. The proper attribution of the film is to the production company. Formally this is a Robert Paul film. Informally, though, I shall think of this family portrait as a Walter Booth film.

1902-1906

Only a few Paul films survive from this period, and the catalogue images are too often not clear enough for a face to be recognisable, so it difficult to know what exactly Booth was doing in the period up to his departure to work for Charles Urban in 1906. In March 1903 he 'gave up-to-date cartoons' at a concert in Hammersmith Town Hall. Sometime between April and June 1904 Sarah gave birth to their second child, Elizabeth Grace, but in Shepherd's Bush. This suggests that the Booth family have moved, but there are other reasons why a woman might want to give birth elsewhere than at her home, and there is no evidence that the family was not in Muswell Hill until Booth changed employers.

Booth appears in one surviving film from this period, A Lively Quarter-Day, or Quarter-Day Conjuring (1906). His rôle is that of a conjurer, moving into a new house. It woud be too fanciful, I think, to suggest that this was some kind of self-reflexive valedictory.

The film was advertised in May 1906, at which point Booth must already have left Paul's employ, because also being advertised in May 1906 was a film he had made for Charles Urban, The Hand of the Artist. The family had moved to Isleworth, which was where Booth made his films for Urban.

One of those films, Comedy Cartoons (1907), again adapts his lightning sketch skills to cinematic ends:

The film was advertised in May 1906, at which point Booth must already have left Paul's employ, because also being advertised in May 1906 was a film he had made for Charles Urban, The Hand of the Artist. The family had moved to Isleworth, which was where Booth made his films for Urban.

One of those films, Comedy Cartoons (1907), again adapts his lightning sketch skills to cinematic ends:

The film features innovative animation, but what strikes me most about it is how much Booth has aged in the six years since Artistic Creation.

Booth's status as an important pioneer of filmmaking rests chiefly with his work made after leaving Robert Paul, and has been well documented.

Walter's son, Sydney, became an engineer in the chocolate industry, living in Bourneville, Birmingham. Walter, born at Worcester on July 12th 1869, died at Bourneville on May 8th 1938.

Booth's status as an important pioneer of filmmaking rests chiefly with his work made after leaving Robert Paul, and has been well documented.

Walter's son, Sydney, became an engineer in the chocolate industry, living in Bourneville, Birmingham. Walter, born at Worcester on July 12th 1869, died at Bourneville on May 8th 1938.

References

Barnes, John (1997), The Beginnings of the Cinema in England, vol.5, Exeter: University of Exeter Press

Barnes, William (2016), Pordenone Catalogue

Christie, Ian (2019), Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema, London: University of Chicago Press

Cook Malcolm (2013), 'The lightning cartoon: Animation from music hall to cinema', Early Popular Visual Culture, vol.11

Cook, Patricia (2016), 'Slade's Electro-Photo Marvel: Touring film exhibition in late Victorian Britain', PhD thesis submitted to Birkbeck College, University of London

McKernan, Luke (2014), 'A Movie Magician': https://lukemckernan.com/2014/12/10/a-movie-magician/

Barnes, John (1997), The Beginnings of the Cinema in England, vol.5, Exeter: University of Exeter Press

Barnes, William (2016), Pordenone Catalogue

Christie, Ian (2019), Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema, London: University of Chicago Press

Cook Malcolm (2013), 'The lightning cartoon: Animation from music hall to cinema', Early Popular Visual Culture, vol.11

Cook, Patricia (2016), 'Slade's Electro-Photo Marvel: Touring film exhibition in late Victorian Britain', PhD thesis submitted to Birkbeck College, University of London

McKernan, Luke (2014), 'A Movie Magician': https://lukemckernan.com/2014/12/10/a-movie-magician/