Le Samourai: places and maps

Giuliana Bruno on Le Samourai (Atlas of Emotion, pp.29-30):

(This piece is an attempt to fill in some of the details in the story about mapping that Bruno sees emerging in Le Samourai from the ruins of film noir.)

1/ places in Paris

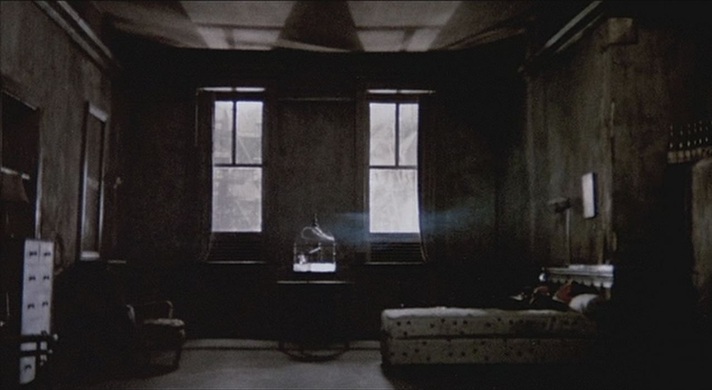

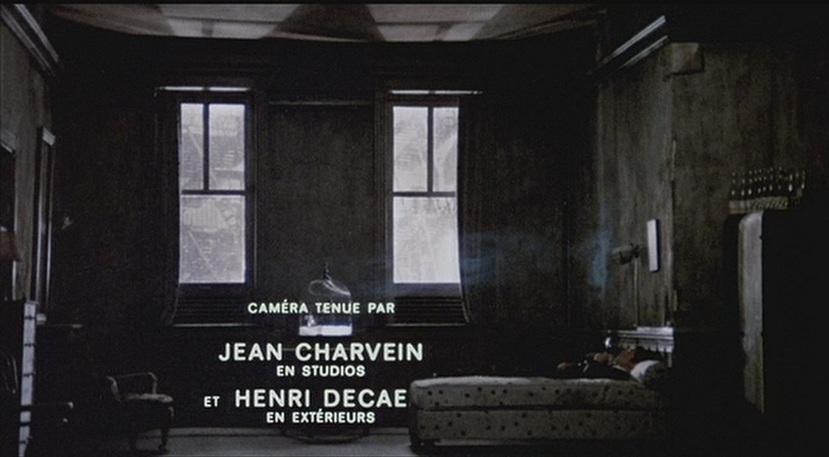

The first two sequences of Le Samourai establish an important topographical contrast in the film: interior vs exterior, studio construction vs real location. The credits, appearing over a view of the interior, include a neat signal of the difference this contrast makes cinematographically, with a page specifying who held the camera in the studio scenes and who held it in the exterior scenes:

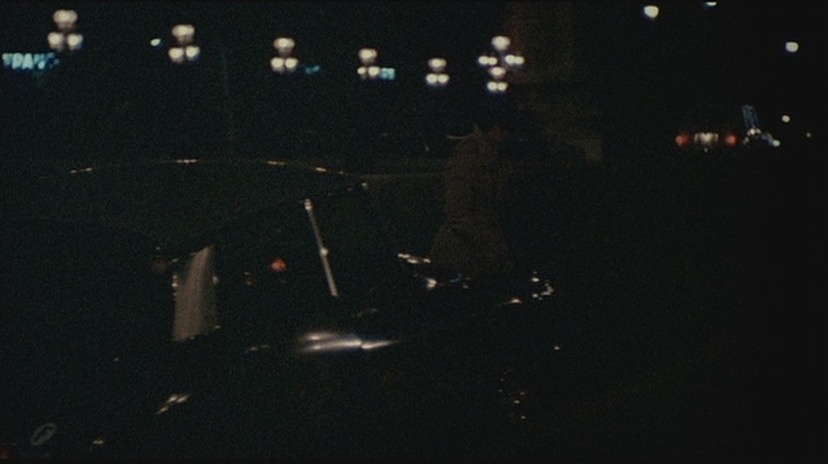

An artificial connection is made between interior and exterior by the backdrop beyond the windows representing stairways, and by the noise of passing traffic added to the soundtrack. This interpenetration has its complement later when back-projection is used to show passing streets in a 'driving through Paris' sequence:

Note also the projection onto the interior's ceiling of shadows from passing traffic outside, and the presence of the rain both as sound heard within the room and as image seen beyond the window.

The relation between inside and outside in this opening is not just a matter of cinematographic contrasts. It informs also how we read the topography of the film. Jef (Alain Delon) emerges from his apartment building onto the street outside. Continuity of time is established by sound (the persistent rain), editing (a clean cut rather than a dissolve) and mise-en-scène (Jef's appearance in the street is as it was in the apartment).

The relation between inside and outside in this opening is not just a matter of cinematographic contrasts. It informs also how we read the topography of the film. Jef (Alain Delon) emerges from his apartment building onto the street outside. Continuity of time is established by sound (the persistent rain), editing (a clean cut rather than a dissolve) and mise-en-scène (Jef's appearance in the street is as it was in the apartment).

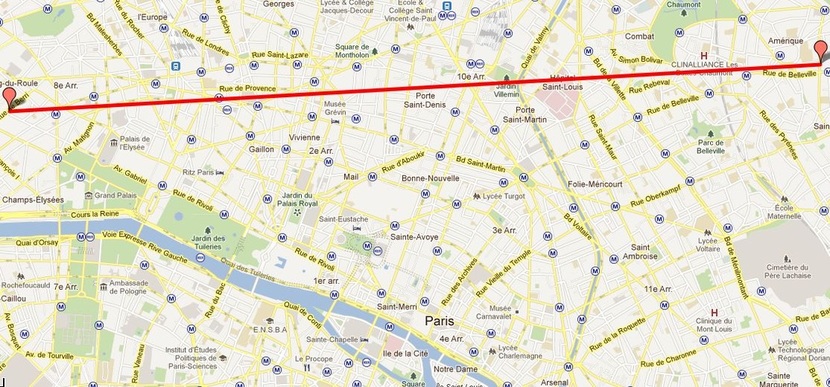

By these same means a continuity of place is also established. However, if we assume that here is the street on which he lives, we have been misled: Jef's apartment building is to the east of Paris, in an impasse off the rue du Docteur Potain; the street onto which he emerges is to the west, the rue de Berri just off the Champs Elysées. (You can see 'now' images of Jef's apartment building here.)

Below is an indication of the distance between shots (almost seven kilometres) :

Below is an indication of the distance between shots (almost seven kilometres) :

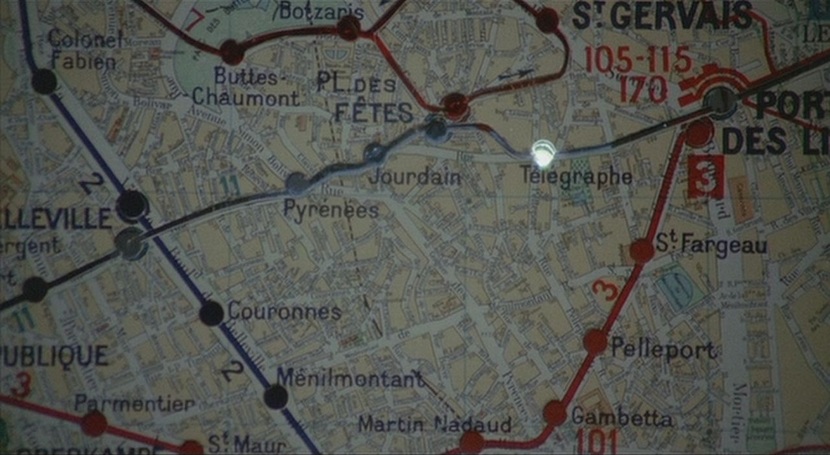

From this leap across the city we may conclude that Le Samourai is not particularly concerned with continuity of place. We cannot have assumed that straightway, however, since in this opening the exact location of Jef's building had not been signalled. That only happens little by little, with recurrent shots of the exterior at night or dawn, but with no topographic detail provided until a late sequence where Jef is shown leaving his apartment, crossing the rue de Belleville and taking the métro at Télégraphe. At that point only can we wonder how he came to be on the rue de Berri, across the city, when first he left that same apartment. But that would depend, of course, on our noting the Berri Bar across the road when he first leaves his building, and remembering what we had noted more than an hour later.

This topographic aporia (a type of topotrope - my neologism) only does its work on a second viewing, when we have discovered how precise the film can be about where it is in place, and also in time (noting the recurrent titles that mark the time, day and date of the action).

This topographic aporia (a type of topotrope - my neologism) only does its work on a second viewing, when we have discovered how precise the film can be about where it is in place, and also in time (noting the recurrent titles that mark the time, day and date of the action).

The recurring locales of Le Samourai give its topography an east-west spread, with Jef’s apartment to the east (1, impasse des Rigaunes, 19e - above) and, to the west, the apartment of his girlfriend (11, boulevard de l’Amiral Bruix, 16e).

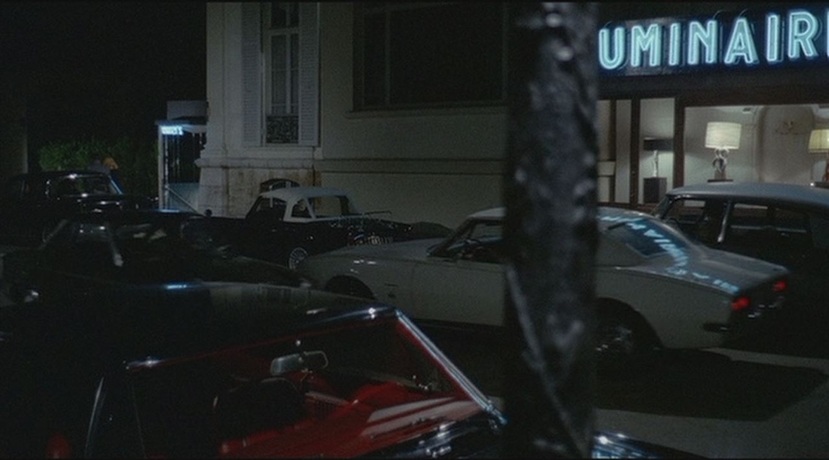

To the west also is, I think, the nightclub whose owner he murders – I haven’t yet located the street , but it looks very much like the area around the Champs Elysees (this piece may have to be radically revised if it turns out to be in quite another part of Paris):

Between these, formulaically, is the quai des Orfèvres (police headquarters), central to the film and, on the île de la Cité, to the city. The exact address is marked with two signs reading ‘36’, just one instance of a redundancy that permeates the film:

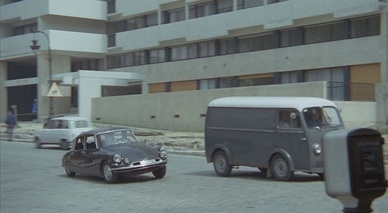

One other recurring locale, the garage where Jef gets the number plates of stolen cars changed, is zone-like and close to anonymous, though again its identification may call for revision of what this piece has to say about place:

[Update 01.04.2017: Yannick Vallet, in the course of his wonderful work on objects and places in Melville's films, found the exact location of the garage, at 118 rue Saint Antoine, in Montreuil.]

Additional nonce locales make this a topography with coverage: a hotel on the boulevard Rochechouart, to the north; a railway station on the boulevard Masséna, to the south east; the pont Alexandre III, central, slightly to the west:

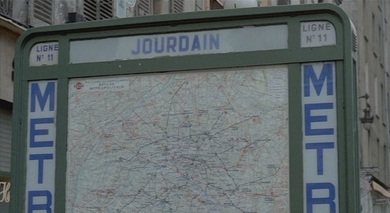

And there are the stations that feature in the film’s two métro sequences: George V, Port Royal, Porte d'Ivry, Télégraphe, Jourdain, Pyrénées, Botzaris, Place des Fêtes, Pré Saint Gervais, Châtelet...

2/ the first métro sequence

After Jef leaves the quai de Orfevres he takes a taxi to ‘1 rue Lord Byron’, just off the Champs Elysées. Going into this building, he is repeating with variations an episode from A bout de souffle, where Belmondo and Seberg go into a building on the rue Lord Byron to emerge by its second exit on the Champs Elysées, at 132:

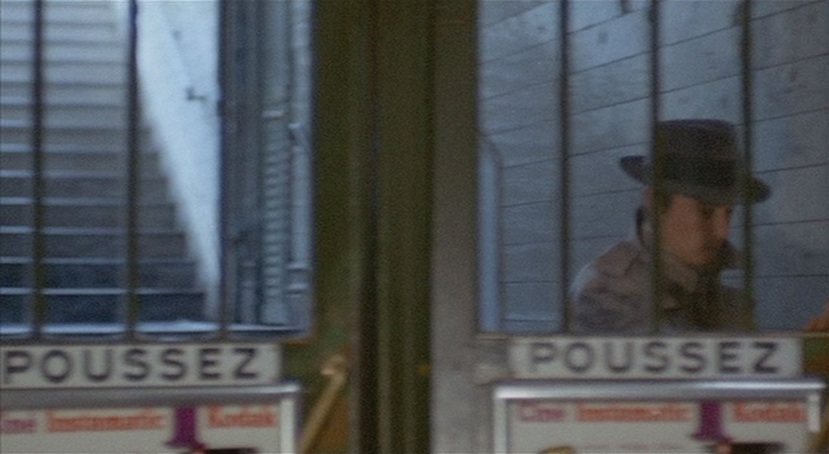

The building Jef comes out of is further down, at number 116. The policeman following him has observed the manoeuvre and is told by his Chief to wait for him to come out onto the Champs, specifying that this exit is next to the cinema Le Normandie. This is the cinema where, earlier in A bout de souffle, Belmondo had contemplated a photograph of Humphrey Bogart before going down into the George V métro station (unaware that the police were right behind him). Jef goes down the same steps, followed by a policeman:

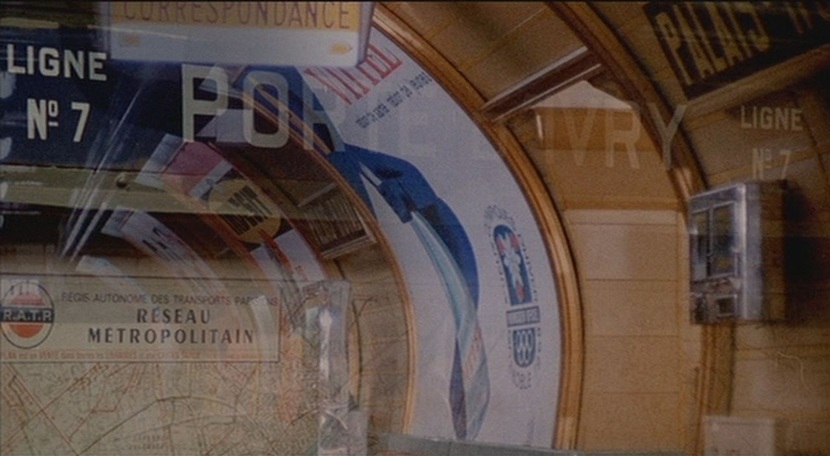

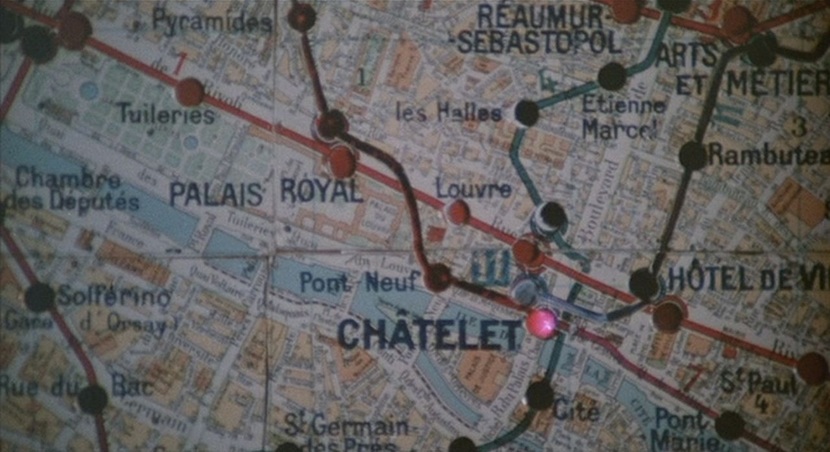

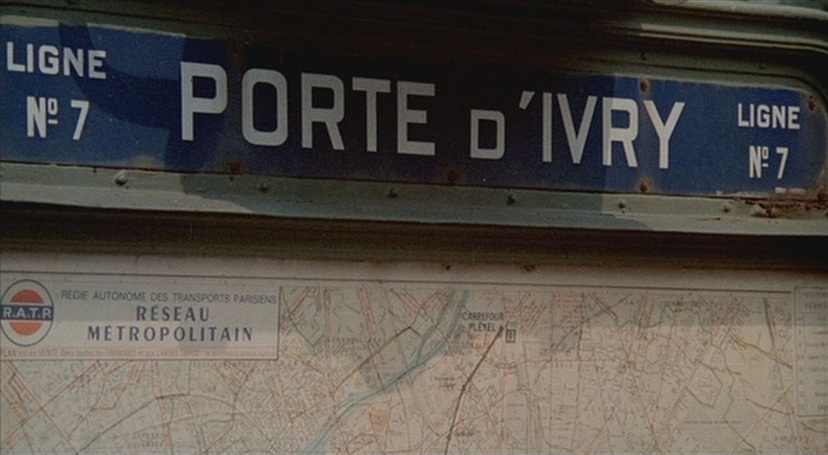

Eluding his pursuer, Jef takes a ligne 1 train to Palais Royal, changes there for the ligne 7, then gets off at Porte d'Ivry. A dissolve neatly combines the names of these two stations with a map of the métro and the key word 'correspondance':

The intertextual repetition by Delon of Belmondo's movements is just one element of the doubling that goes on in this sequence. As Delon emerged onto the Champs there was a poster next to the cinema of someone who looks very much like him:

|

Actually this is Maurice Ronet in Louis Malle's Ascenseur pour l'échafaud; through the grill we can see that this is the film playing at the Normandie. The intertextual signpost points to the difference between Ronet's character, who is trapped in a lift for most of Malle's film, and Jef, who has just without difficulty taken two lifts to shake off the policeman following him:

|

Before we see Delon getting off the first métro at Palais Royal, he is preceeded by a similarly dressed man whom we could easily mistake for Delon.They end up in shot together, just before Delon turns to get to the ligne 7 platform:

This is a mild form of the extreme doubling that occurs when we see the Chief Inspector interrogating a Delon-lookalike:

3/ the second métro sequence

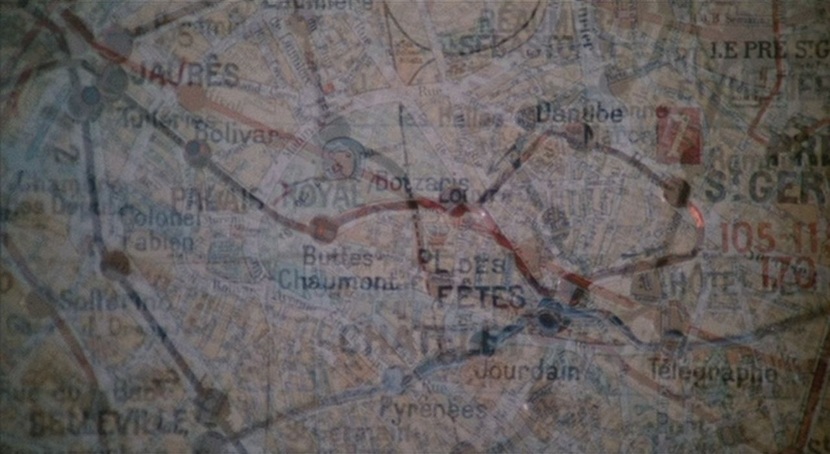

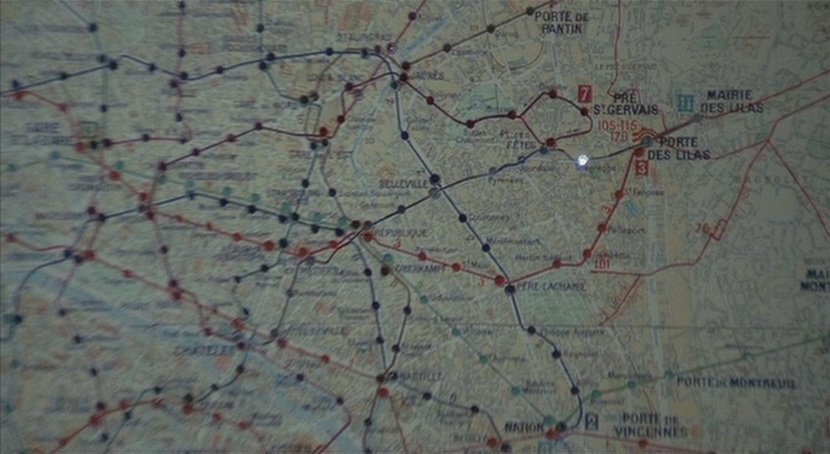

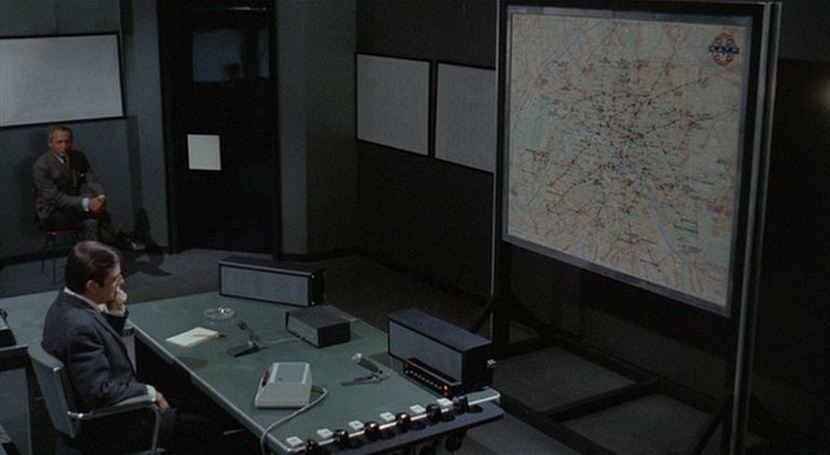

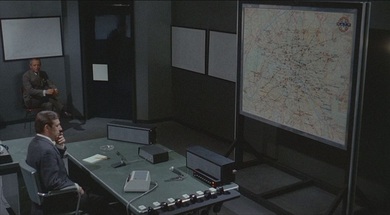

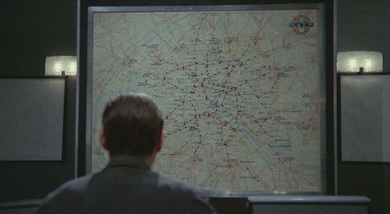

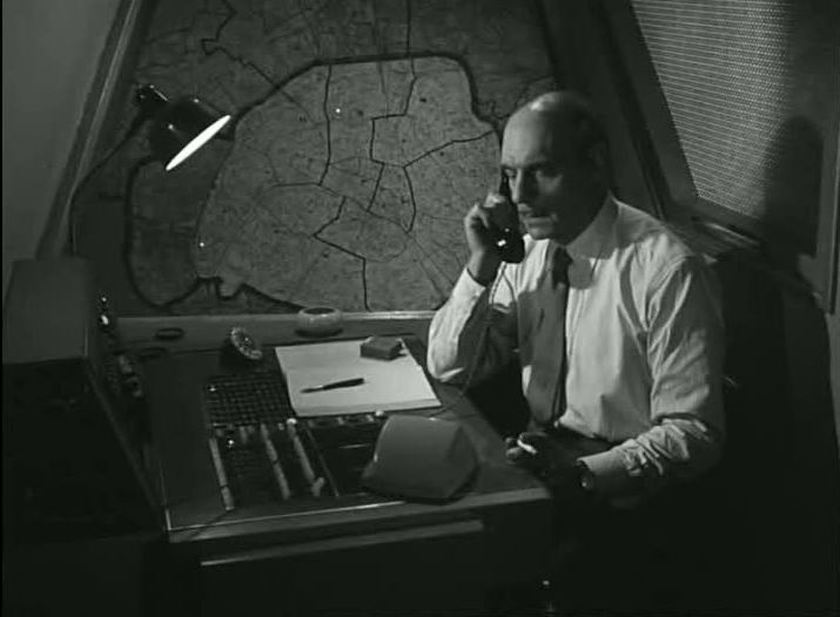

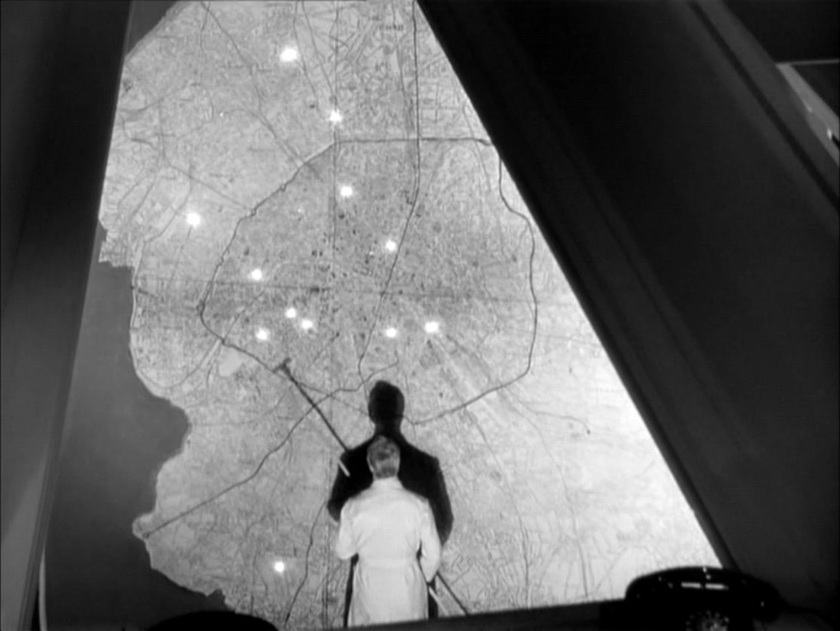

This sequence also plays with repetition, not least of the earlier sequence, but it is altogether a more complexly layered composition. It begins with Jef going down into the métro at Télégraphe, the which is reported by a watching policeman back to headquarters, where a map of Paris showing the métro system is being monitored by the Chief Inspector. He has a large number of agents positioned in and around the métro in this vicinity, some on the surface with car-telephones and some underground with a transmitter system that allows Jef's movements to be tracked on the map:

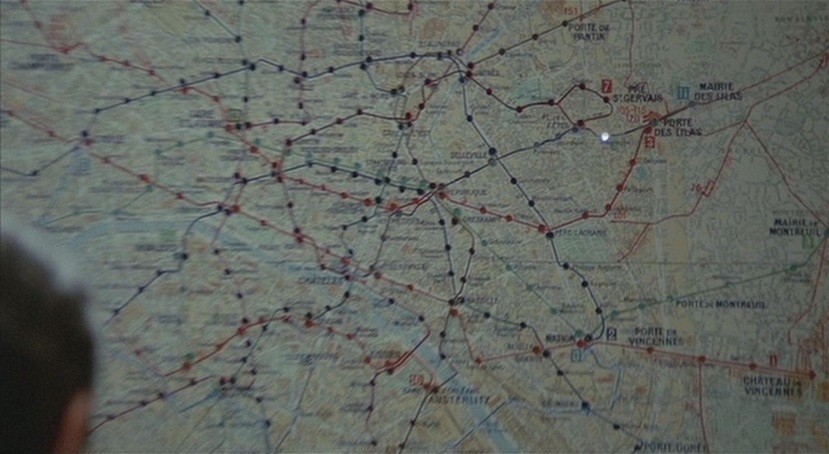

From Télégraphe Jef takes a westbound train, ligne 11, heading for Châtelet. Two stops along, at Jourdain, he jumps off at the last minute and makes his way onto the platform for trains going in the opposite direction, towards Mairie des Lilas. At the next stop, Place des Fêtes, he gets off and goes to the platform for ligne 7, from which he can get a train that will also take him to Châtelet, if by a more circuitous route than his original choice of line would have done. One map dissolves into another to show the signal that tells the Chief Inspector Jef has arrived at Châtelet, still being followed by the policewoman who picked up his trail at Place des Fêtes:

This sequence engages with the topography of Paris at three levels:

a/ the métro itself, an underground arrangement of tunnels, corridors, foyers and staircases, with its distinctive furnishings, décor and signage, and as defining feature the regular coming and going of trains. We are told that Jef knows this world 'like he knows his own pockets', though really the knowledge he demonstrates is little more than what the average habitual user of the system would know. Anyone with the ability to read any one of the many maps that are everywhere in and around the métro can find their way around it, and if we don't see Jef consult one of these maps - indeed if he appears to studiously ignore them - that only means that he knows where he is going and how to get there.

a/ the métro itself, an underground arrangement of tunnels, corridors, foyers and staircases, with its distinctive furnishings, décor and signage, and as defining feature the regular coming and going of trains. We are told that Jef knows this world 'like he knows his own pockets', though really the knowledge he demonstrates is little more than what the average habitual user of the system would know. Anyone with the ability to read any one of the many maps that are everywhere in and around the métro can find their way around it, and if we don't see Jef consult one of these maps - indeed if he appears to studiously ignore them - that only means that he knows where he is going and how to get there.

b/ the city at street level. The sequence shows seven different surface locales, each of them because it is a point of entry and exit from the métro system. If the soundtrack identifies some of these, it is in the image that location is exactly specified:

In passing these above-ground views show something more of the city: soon-to-be-demolished buildings on the rue de Belleville; the 1850s' church of Saint Jean-Baptiste; newly built apartments on the rue de Crimée; the théâtre Sarah Bernhardt on the place du Châtelet:

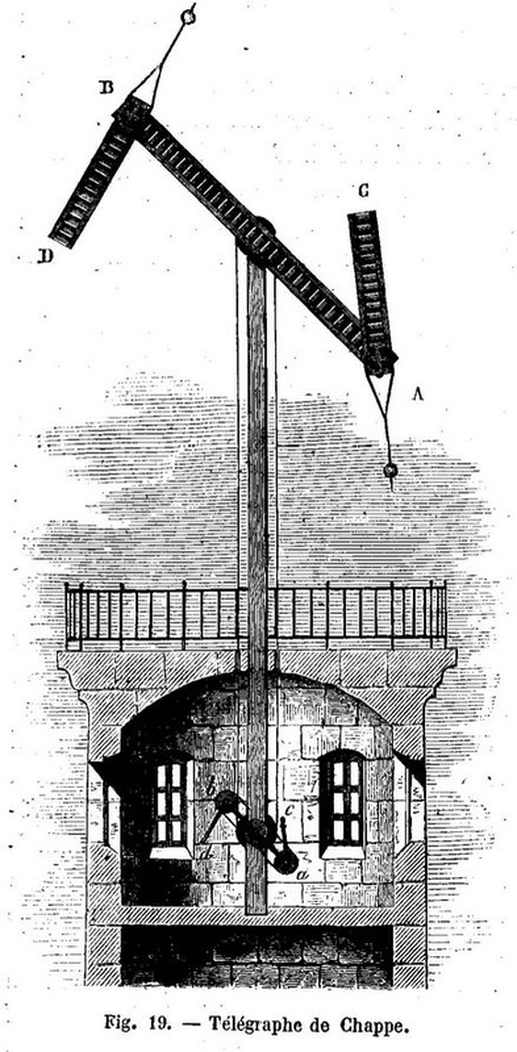

But what they chiefly show is the city refigured in terms of the schematic simulacrum below ground. The one-word station names, especially, are reductions of the locale to a convenience (saving space and time). The 'rue du Télégraphe' invites inquiry into the origins of its name (see here for a brief account, in French); 'Télégraphe', on the other hand, is, well, telegraphic, it's just a name. The relation between station names and street names is generally symbiotic, but the métro's tightening hold on the city's nomenclature is a discernible phenomenon since the first line opened in 1900.

c/ At the third level of this sequence's engagement with the topography of Paris, the ascendancy of the underground over the surface is also manifest. Movements at the two other levels are registered at the control centre, tracked on a map by the Chief Inspector:

The map he is studying is of a standard type published by the Paris transport authority (the RATP), one which naturally privileges the underground network, laying it out on the surface of the city, to the point of obscuring street and place names. The rue de Crimée, for example, has entirely disappeared from this map:

The Chief Inspector's overview might suggest that he has at his disposal a superior knowledge of the métro system. What his map doesn't show, however, is the topography of the métro beyond the actual train lines. It doesn't show the stairways and corridors, nor the various entrances and exits. Though, as I have said, Jef's knowledge of the métro is no more impressive than that of any regular passenger who knows where they're going, at Châtelet he demonstrates a little more savoir-faire. He takes the moving walkway that leads from the ligne 7 platform to the platforms for other lines. (This engineering novelty - installed in 1964 - is not on the Chief Inspector's map.) Halfway along Jef jumps from the walkway and runs back in other direction, leaving the following policewoman behind. That is how he eludes the scrutiny of the Chief Inspector, watching from two levels above.

From Jef's descent into the métro at Télégraphe to his emergence at Châtelet, the sequence lasts about eleven minutes, which corresponds, roughly and ironically, to the real time this would have taken him had he gone by the direct route. Rather than ten stops on the one line, Jef's actual journey goes through twenty-one stops with two changes. Seventeen of these stops are covered by the dissolve just before he arrives at Châtelet, leaving the earlier part of the journey shown in something like real time.

Had the film been made six months later, this journey would have been even longer. In December 1967 the section of ligne 7 between Louis Blanc and Pré Saint-Gervais, which had until then been one of two branches, was formally separated from the main part of the line (and renamed ligne 7bis), such that Jef would have had to change once more at Louis Blanc to get a train for Châtelet.

As it is, Jef's decision to switch onto the branch of ligne 7 isn't necessarily a sound one. The branch has the peculiarity of becoming a single, unidirectional line after Botzaris, making a loop before heading back. This means that if he gets off at Pré Saint Gervais or Danube he doesn't have the option of doubling back to elude his pursuer.

Furthermore, in taking a line that like the other goes to Châtelet, he is surely signalling that station to the police as his likely destination.

What is remarkable is not so much that Jef wins because he best knows the map, but that the police conduct this operation so incompetently as to let him get away. Seventy agents are deployed in the métro with more at the surface, and yet when Jef arrives at Châtelet they don't manage to cover all the exits, and Jef by chance emerges from an exit they have missed. Their plan seems to have been to have cars waiting at every possible station on his journey in case he should come out there, but they might reasonably have concluded that Châtelet, with its multiple intersections and exits, needed better coverage.

What is remarkable is not so much that Jef wins because he best knows the map, but that the police conduct this operation so incompetently as to let him get away. Seventy agents are deployed in the métro with more at the surface, and yet when Jef arrives at Châtelet they don't manage to cover all the exits, and Jef by chance emerges from an exit they have missed. Their plan seems to have been to have cars waiting at every possible station on his journey in case he should come out there, but they might reasonably have concluded that Châtelet, with its multiple intersections and exits, needed better coverage.

I may be being unfair to the Chief Inspector. Though everything points to Châtelet as his destination, in fact Jef could have left the métro at any one of its 347 stations, since his destination was any place where he could steal a car unobserved.

It is by chance that he came out at Châtelet, and by chance that he eluded the police there.

It is by chance that he came out at Châtelet, and by chance that he eluded the police there.

4/ stairs and levels

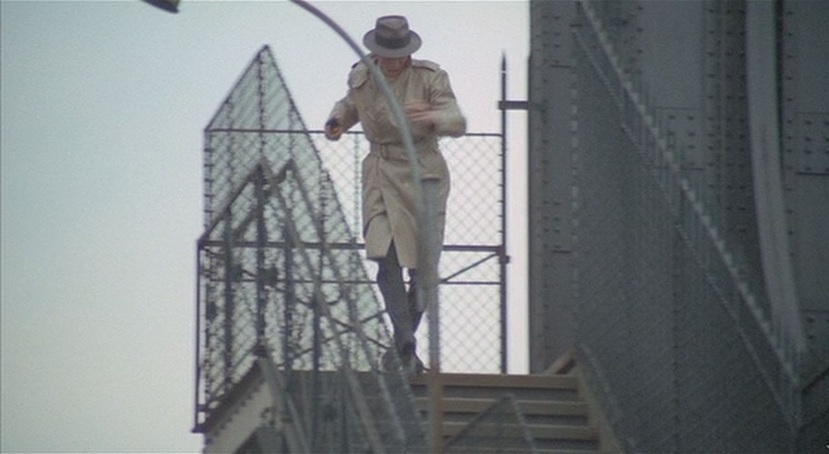

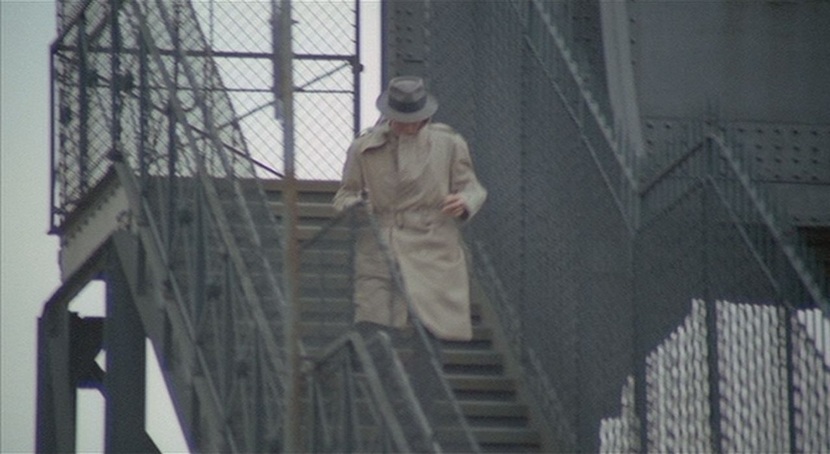

If we read the métro as a map, a set of lines arranged on a flat surface, the second sequence suggests an arbitrariness or redundancy in the notion of direction and destination. This is different from the earlier sequence where, having eluded the policeman following him from the quai des Orfèvres, Jef goes in a precise direction towards a specific destination, for a rendezvous at a fixed time. He gets off the métro at a frontier, Porte d'Ivry. Not the end of a line but the last point on the line before it leaves Paris:

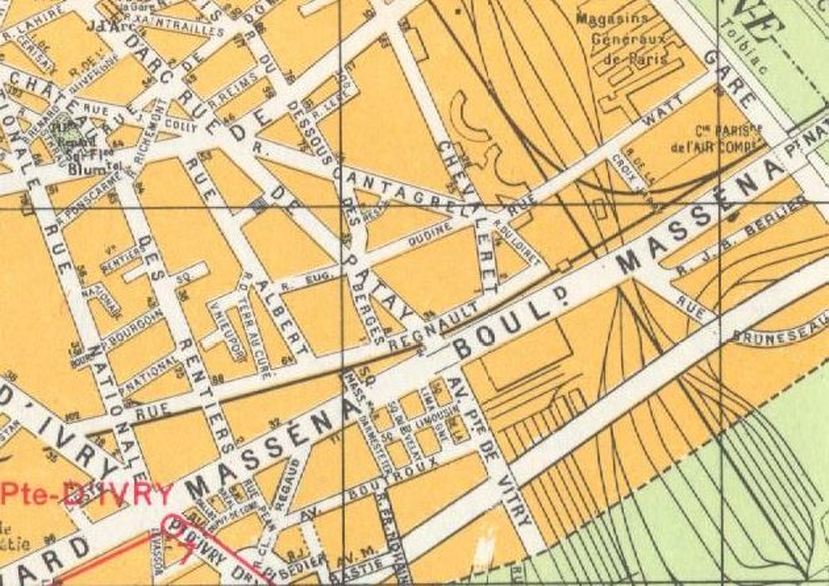

His rendezvous, however, is at a different station, the connection with which he has to make by walking. He remains within Paris, though still at its edges. By the boulevard Masséna he reaches an overground railway station originally called Orléans-Ceinture - on the map below it is near the corner of the rue Regnault and the rue du Loiret. His rendezvous is on a footbridge that crosses the railway lines and leads to the rue de la Croix Jarry. [This footbridge has sometimes - including by me - been wrongly identified as the one on which Jeanne Moreau ran her famous race in Jules et Jim, but that footbridge is at Charenton-le-Pont - see here Patrick Six's brilliantly thorough photo-essay on that location.]

Though the endpoint of his first métro journey, this elevated position is the antithesis of the métro - trains pass beneath the two men as they meet. Excepting the fourth-floor corridor that links the two lifts by which Jef earlier eluded a a tailing policeman, this is the most elevated place in Le Samourai, a film that stays mostly at or below street level (compare with the Belmondo vehicle Peur sur la ville, here, a film that also has a chase in the métro but which spends most of its time looking down on the city from very high up).

Though the endpoint of his first métro journey, this elevated position is the antithesis of the métro - trains pass beneath the two men as they meet. Excepting the fourth-floor corridor that links the two lifts by which Jef earlier eluded a a tailing policeman, this is the most elevated place in Le Samourai, a film that stays mostly at or below street level (compare with the Belmondo vehicle Peur sur la ville, here, a film that also has a chase in the métro but which spends most of its time looking down on the city from very high up).

This conclusion to Jef's journey is like a straight line drawn across the map.

The framing here, suggesting horizontal extension into the distance, occurs also at lower levels, ground and underground:

The framing here, suggesting horizontal extension into the distance, occurs also at lower levels, ground and underground:

The counterpart to this interest in horizontality is the recurrence of stairways. Jef himself goes up or down fifteen different sets of stairs in the film (and also goes up or down in three different lifts). Some of these stairways occur in succession, as in the escalographic (my neologism, see here) sequence leading to the encounter on the footbridge:

A staircase also figures in the aftermath of that encounter:

5/ all the maps

Maps appear in four types of place in Le Samourai. Two are directly tied to the métro sequences, where maps are a part of the given décor. The first of these is the entrance to a métro station, as here:

The second is in the station itself, either in the foyer or on the platform. The map need not be of the métro, since station foyers feature maps of the vicinity, and maps of other transport networks (e.g. the buses) also appear on station platforms:

The third place is in the Chief Inspector's office. As backdrop to a succession of interrogations, briefings with colleagues and solitary ruminations he has a copy of the 1739 Bretez-Turgot map of Paris (see here), a wonderful artefact but of no practical use in modern police work:

Modern police work is conducted in a dedicated map room, adorned with at least nine unreadable but seemingly identical monochrome maps (presumably of Paris), positioned discretely around the quai d'Orfèvres's chef d'oeuvre of cartographic policing, the map that is the object at the centre of the film's most celebrated sequence:

This object is, as I have said, a standard RATP map (though I haven't found exactly the context in which it might have been used), but it has been manipulated to perform the sophisticated task asked of it by the film. Rather than find some existing giant lighted map that could respond to transmitted signals, into this map's paper surface have been cut holes and lines, though only in those places that correspond to Jef's anticipated trajectory. We can see, for example, in the close-up below that no lighting mechanism could have informed the Chief Inspector if Jef had gone to Porte de Lilas and changed onto line 3:

The choice to adapt only the part of the map that relates to the story is understandable, but we might here ask why it is this part of Paris that was given a place in the story in the first place. A clue may lie in the method of surveillance deployed in this sequence, tracking Jef with 'gallium arsenide transmitters' . An ancestor of this modern technology is signalled in the name of the station at which Jef descends into the métro: 'Télégraphe'. This place name refers to Claude Chappe's telegraphic system, installed in the vicinity in the 1790s. It is possible that this part of Belleville was made central to the film's topography solely in order to make this connection between two technologies across two centuries.

My research is ongoing as to whether the Paris police would at the time, or indeed ever, have had at their disposal anything like the kind of surveillance equipment we see in La Samourai. (See here for a film showing the Paris police using a different tracking procedure.)

The idea would seem feasible to Parisians familiar with the PILI, the 'Plans Indicateurs Lumineux d'Itinéraires', illuminated journey-planning maps first installed in the Paris métro in 1937:

The idea would seem feasible to Parisians familiar with the PILI, the 'Plans Indicateurs Lumineux d'Itinéraires', illuminated journey-planning maps first installed in the Paris métro in 1937:

And readers of Simenon's Maigret novels would know of the giant lighted map at the headquarters of Police-Secours, indicating incidents all over Paris to which the emergency services would be sent:

But Melville's film is not a police procedural, and his cartographic construction is not - I'd conjecture - a record of police surveillance methods circa 1967. It is an invention, something more like the lighted map of London in Alfred Vohrer's 1966 film The Hunchback of Soho, a horror fantasy filmed entirely in Germany:

Or even like the 'Giant Lighted Lucite Map of Gotham City', here in a 1966 episode of Batman ('Instant Freeze'):

Conclusion

I agree with Giuliana Bruno that Melville's film is a lesson in cartography, but would be reluctant to concur that 'ultimately Le Samourai tells no other story than that of the subway map of Paris', because the configuration of that map in this film is not in any sense a story. The maps in Le Samourai, alongside its staircases and window frames, its car journeys and train rides, its zooms and pans - and that wonderfully strange, almost imperceptible back and forth movement of the camera in Jef's room, just after the credits, when you're not sure if it's you rather than the film that is wavering - and so much else, all these are readings of space, simply. Who needs a story?

(In case you're wondering, I don't think you can see from these grabs the slight shifts in framing that happen in that moment after the credits. I put them here to suggest you might want to go and watch the film, closely.)