Un flic: art and artifice

(and also cars and hats and blondes)

(and also cars and hats and blondes)

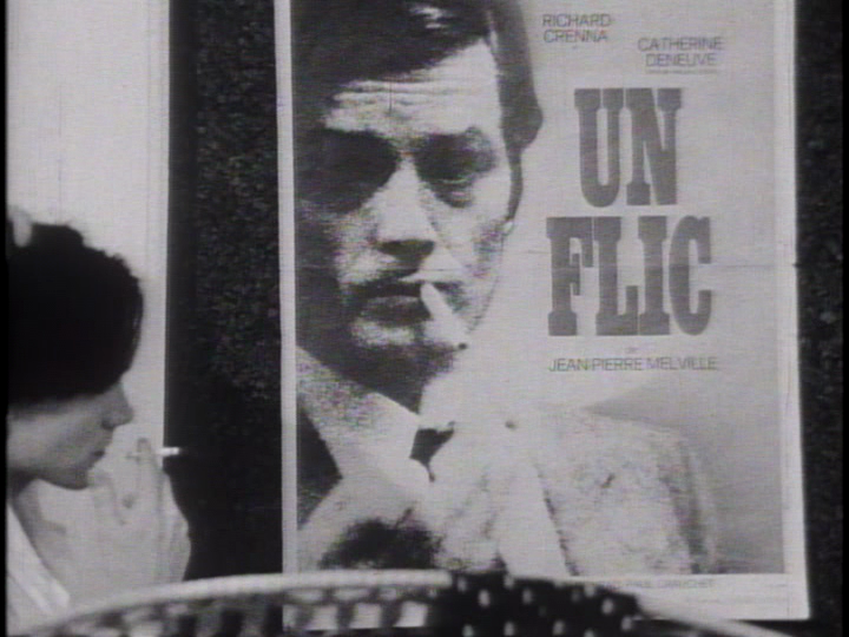

Jean-Pierre Melville's last film Un flic (1972) reprises several patterns and procedures familiar from his earlier work, along with actors and locations, all worked into a mode of elegiac intertextuality that we can call Melvillian.

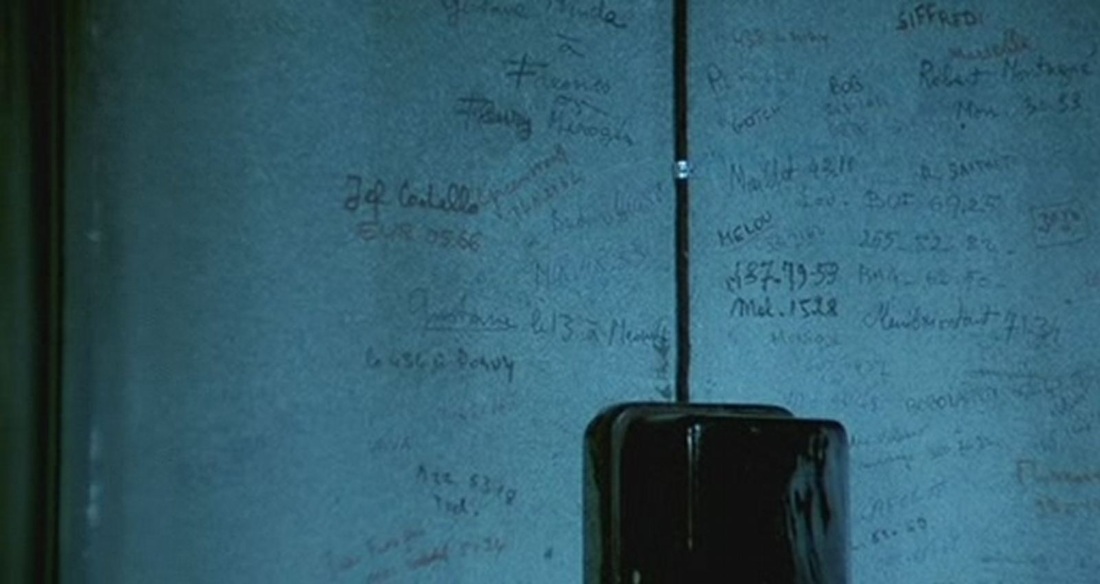

A fleeting instance of this manner is the view of names and phone numbers on a wall in the apartment of a dead prostitute. Among the names we can make out are those of Robert Montagné, 'Bob' from Bob le flambeur (1956), Gustave Minda, from Le Deuxième Souffle (1966), and Jef Costello, from Le Samouraï (1967), all films by Melville.

A fleeting instance of this manner is the view of names and phone numbers on a wall in the apartment of a dead prostitute. Among the names we can make out are those of Robert Montagné, 'Bob' from Bob le flambeur (1956), Gustave Minda, from Le Deuxième Souffle (1966), and Jef Costello, from Le Samouraï (1967), all films by Melville.

Coleman, the policeman who looks at these names, comments that 'on va avoir du boulot' ('We 'll have work to do'); the actor playing that policeman is Alain Delon, i.e. Jef Costello. The names by the phone also include two other roles played by Delon, Siffredi in Jacques Deray's Borsalino and 'Gotch' in Terence Young's Red Sun (both 1970). If the 'R' in R. Sartet stands for Robert then that is Delon's character in Le Clan des Siciliens (Henri Verneuil 1969).

The intertextual scheme of Un flic implicates both characters and actors: Coleman's assistant Morand is played by Paul Crauchet, who had appeared with Delon in Le Cercle rouge (1970), as a fence. The next call they make is on the victim of a robbery, played by Jean Desailly, the police inspector in Melville's Le Doulos (1962), a crime drama in which Desailly investigates the murder of a fence.

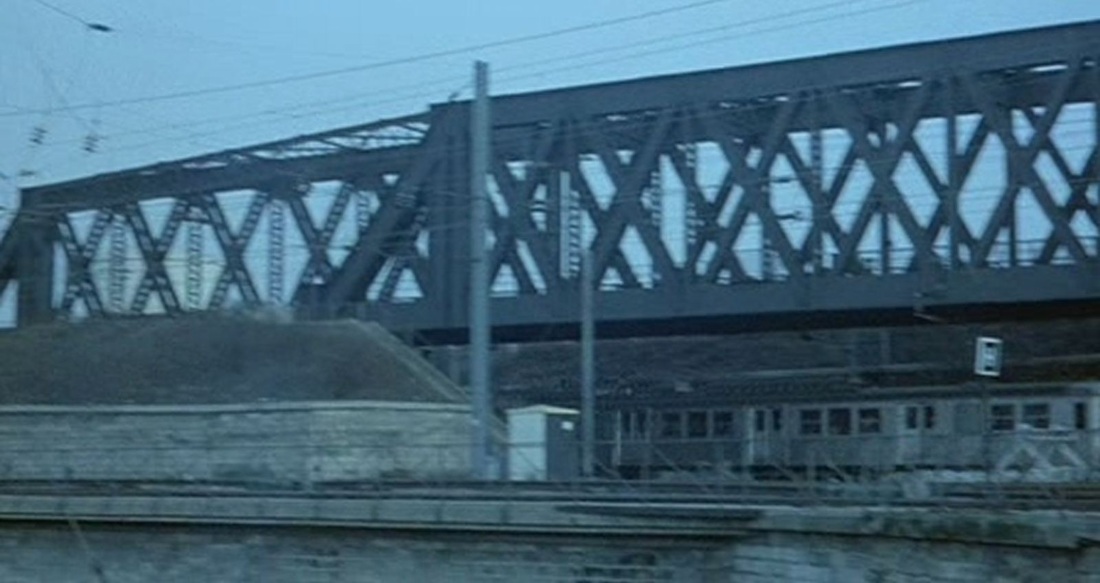

Places, likewise, are implicated. The house where the fence was murdered in Le Doulos was near a railway bridge, and we see that same bridge in Un flic:

The intertextual scheme of Un flic implicates both characters and actors: Coleman's assistant Morand is played by Paul Crauchet, who had appeared with Delon in Le Cercle rouge (1970), as a fence. The next call they make is on the victim of a robbery, played by Jean Desailly, the police inspector in Melville's Le Doulos (1962), a crime drama in which Desailly investigates the murder of a fence.

Places, likewise, are implicated. The house where the fence was murdered in Le Doulos was near a railway bridge, and we see that same bridge in Un flic:

(I haven't yet worked out where this bridge is, but I think it is somewhere near the cimetière de Saint Ouen, north of Paris.)

A brief view in Un flic of the place Pigalle recalls the use of that location in Bob le flambeur:

A brief view in Un flic of the place Pigalle recalls the use of that location in Bob le flambeur:

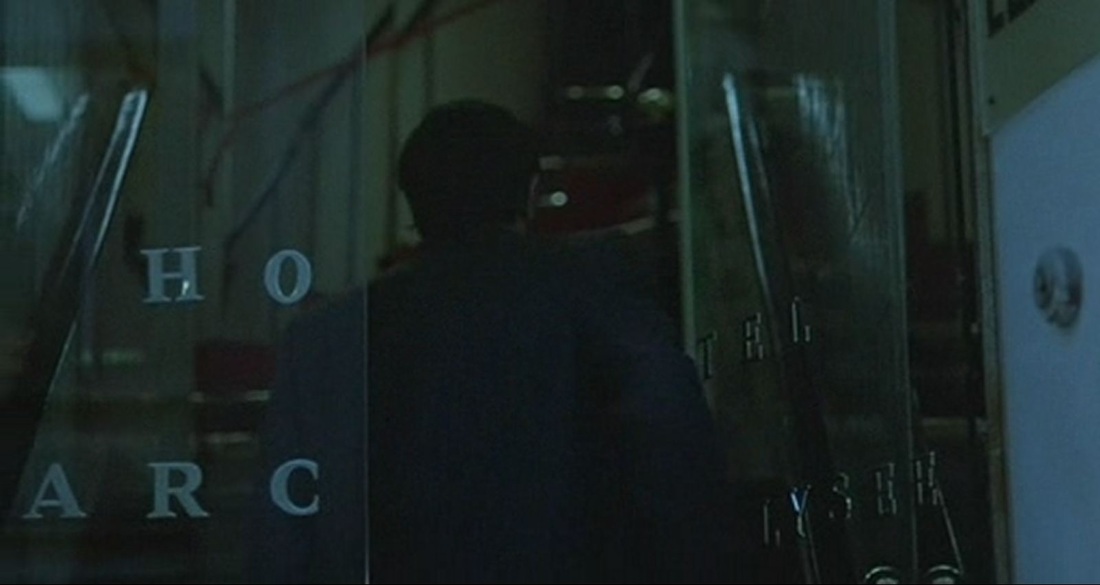

When, in Un flic, Delon calls on Catherine Deneuve at the Hôtel Arc Elysées, 45 rue Washington, Melville is back at a principal location for Le Deuxième Souffle. Ricci's restaurant in that film is at 23 rue Washington, and in the view below left you can see the hotel's sign further up the street:

Objects, also, can be signposts to other films. In Le Samouraï, police efforts to track Delon's character in the streets and then the métro system involve frenetic use of the carphone:

By contrast, in Un flic the attitude of Delon's character towards using the carphone is one of bored indifference, mimicked in the script by the use of the same dialogue on four separate occasions.

Morand answers the phone, then passes it to Coleman:

- Car number 8. I'll put him on.

- Yes? Where's that? We're on our way, I'll call you back afterwards.

Morand answers the phone, then passes it to Coleman:

- Car number 8. I'll put him on.

- Yes? Where's that? We're on our way, I'll call you back afterwards.

Monotone telephony in Un flic also has its internal textuality, since the dramatic climax of the film involves information discovered through the tapping of calls, shown with shots of the inner working of the telephone system:

Patterning across different films and across different parts of the same film is a basic component of Melville's art. The shots of telephone equipment above illustrate another such component, a pleasure taken in the form of objects. This pleasure is expressed in showing the object itself, but also in discovering correspondences between objects, as when the exposed switches at the telephone exchange echo the exposed hammers of the piano Delon had played earlier:

Melville takes pleasure also in architectural forms, and we can see the shapes in the telephone exchange and inside the piano echoed in the façades of buildings:

(Jacques de Brauer's office building above, at 72 rue Regnault, 13e, had just been completed when Melville borrowed it for Un flic.)

For pleasure in the thing itself, the chief objects, across almost all of Melville's cinema, are American automobiles:

For pleasure in the thing itself, the chief objects, across almost all of Melville's cinema, are American automobiles:

These objects are beautiful and also functional. One of their functions is to carry into these French films an idea of the United States, not just a memory of older films from a noir or gangster tradition, but a strong sense of modern Americana (these are not yet vintage cars).

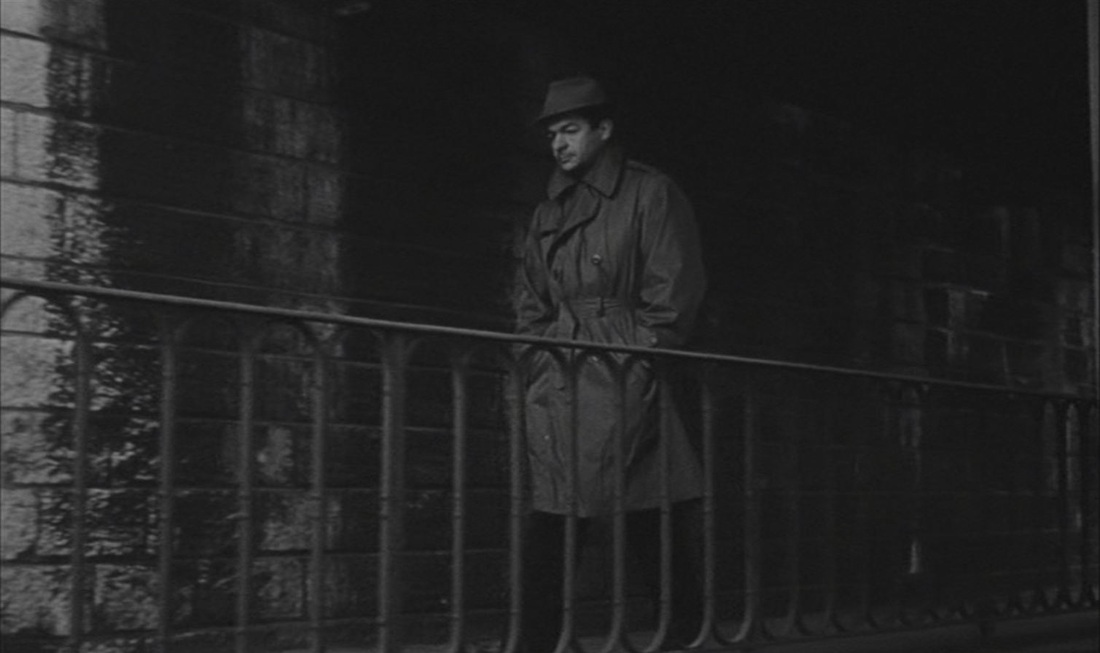

Another recurrent object in Melville makes similar associations, but its use changes over time to make it a sign of change over time. In Bob le flambeur and Le Doulos the fedora is naturally associated with the criminal hero. Here it accompanies his moments of self-interrogation:

Another recurrent object in Melville makes similar associations, but its use changes over time to make it a sign of change over time. In Bob le flambeur and Le Doulos the fedora is naturally associated with the criminal hero. Here it accompanies his moments of self-interrogation:

As eponymous object, the hat in Le Doulos becomes a more freely floating signifier, establishing formal correspondences between the two principals, Reggiani ('Faugel') and Belmondo ('Silien'):

In Le Deuxième Souffle fedoras are still the accoutrements of gangsters and policemen, though for the hero Minda (Lino Ventura) it is a kind of disguise, and he looked more at his ease in a beret:

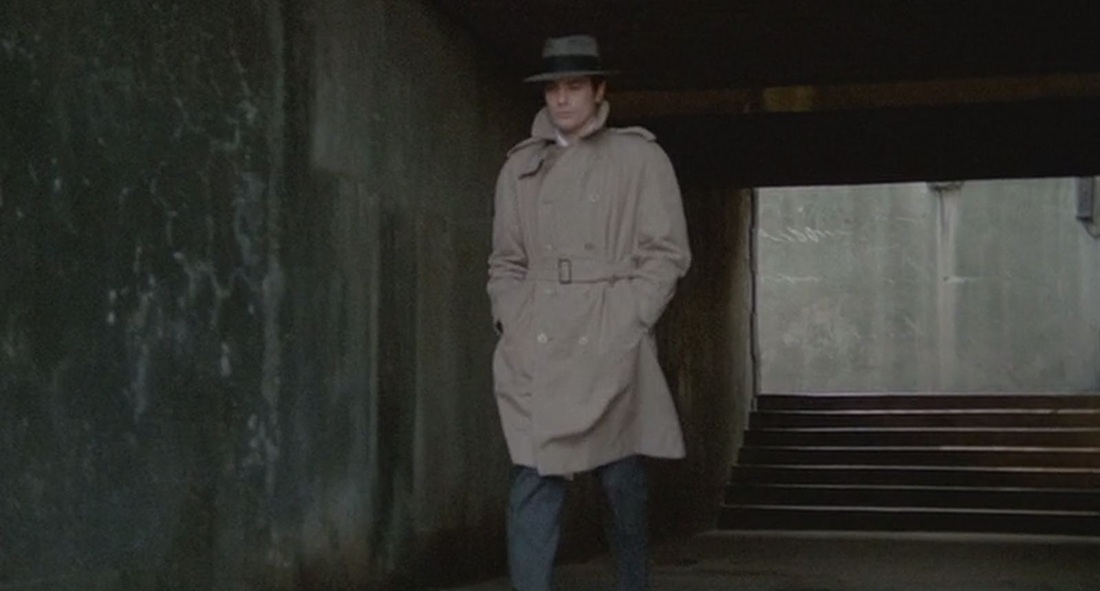

For Jef in Le Samouraï the hat is part of a ritually donned uniform and, when combined with a trenchcoat and a walk down urban corridors, serves to connect him intertextually with Faugel in Le Doulos:

The two men are, incidentally, very close to each other topographically, in the 13e arrondissement: Delon is on a staircase by the old Orléans-Ceinture railway station, about to emerge onto the rue Regnault, near one end of the rue du Loiret; Reggiani is in the part of the rue Watt that passes under railway lines, and is about to emerge near the other end of the rue du Loiret. At a stretch they might have seen each other:

The big difference between Delon in Le Samouraï and Delon in his next film with Melville, Le Cercle rouge (1969), is that in the latter he wears a moustache and doesn't wear a hat:

Fedoras in Le Cercle rouge are reserved for old-school gangsters and old-school policemen, as played by men older than Delon (Yves Montand, Bourvil, François Périer and Bourvil again, in disguise):

Le Cercle rouge supplies the emblematic view of this motif, a police photographer fixing the image of a dead gangster, with his gun and fedora:

In Un flic, fedoras are worn by bank robbers (left) and pickpockets (right):

But Delon is once again hatless throughout the film, a motif that allows his dishevelled, windswept hair to signify his distress at having had to kill his friend in the last action of the film:

In this décoiffé state he enters into a last exchange of looks with an equally décoiffée Catherine Deneuve:

For the men in Melville's crime films Delon's dishevelled hair is the endpoint of a chain that began with the well-groomed Bob Montagné looking into the mirror and commenting: 'Une belle gueule de voyou'.

For the women in Melville's crime films there is no such continuity. Un flic is the only one of those eight films with a female star of any substance, so the mise-en-scène of Deneuve cannot continue or deviate from an established pattern. In this respect Melville is no Hitchcock, and though there are recurrent blondes in his films, it cannot be said that Isabelle Corey, Monique Hennessy, Christine Fabréga, Nathalie Delon and Anna Douking are a match for Grace Kelly, Kim Novak, Janet Leigh and Tippi Hedren.

For the women in Melville's crime films there is no such continuity. Un flic is the only one of those eight films with a female star of any substance, so the mise-en-scène of Deneuve cannot continue or deviate from an established pattern. In this respect Melville is no Hitchcock, and though there are recurrent blondes in his films, it cannot be said that Isabelle Corey, Monique Hennessy, Christine Fabréga, Nathalie Delon and Anna Douking are a match for Grace Kelly, Kim Novak, Janet Leigh and Tippi Hedren.

Melville's alternative in Un flic is to construct a pattern internal to the film, beginning with the very first woman (almost) to appear on screen, eighteen minutes in:

Delon's opening vis-à-vis with the dead prostitute announces the closing vis-à-vis with Deneuve:

Between that beginning and end Delon has other exchanges with blonde women, as here with a cabaret dancer:

The motif is reprised in the blondness of Coleman's indicatrice, a transvestite, whose relation with Coleman is initially marked by tenderness (she is the only one who calls him Edouard):

By the end she is rejected, beaten up and cast out into the street, but in the meantime Deneuve has arrived on screen and the mise-en-scène of her lethal blondness effaces all else:

Against a background of dead prostitute and transvestite informer, Deneuve's infidelity, treachery, and the murder she commits are as nothing. She is all photogénie, Melville's answer to Hitchcock's Grace Kelly:

A cine-memory suggests one last counterpoint to the rendering of Deneuve's coiffure and physiognomy. The wife of one of the aged bank robbers is played by the blonde Simone Valère, a star in fifties cinema and a doyenne of postwar theatre, along with her partner Jean Dessailly. Here they are together in Le Voyageur de la Toussaint (Louis Daquin 1943):

And this is Simone Valère in La Beauté du Diable (René Clair 1950) and (the one on the right) in Ma femme est formidable (André Hunebelle 1951):

However formidable may be the wife she plays in Un flic, I don't really think the memory of her former roles is strong in Melville's film. Not, at least, to the degree it is for Jean Dessailly, who is also in Un flic, though not paired with Simone Valère.

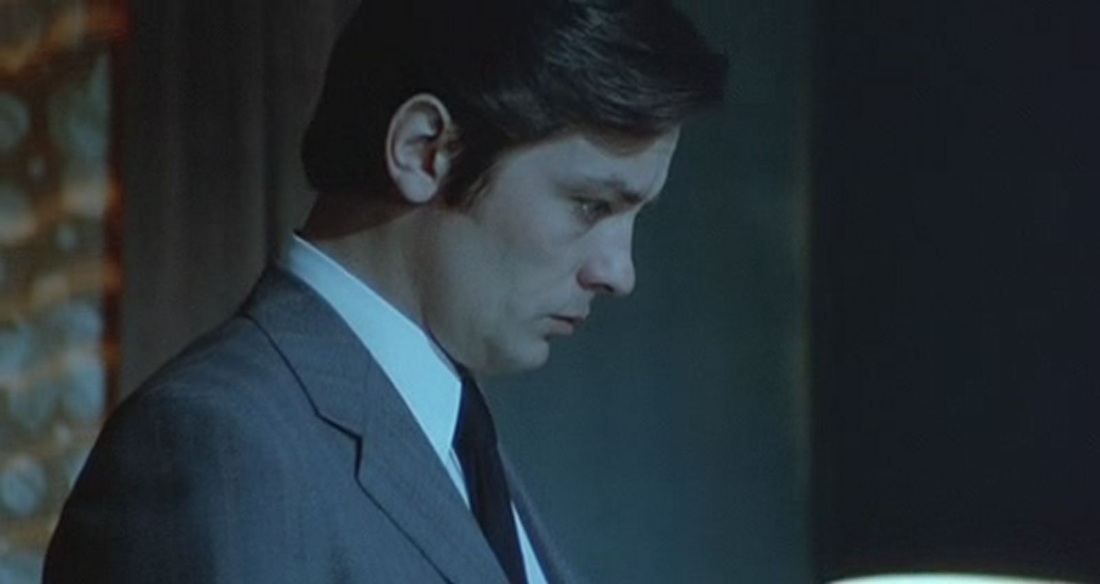

Here he is in Un flic as the homosexual art collector who has been robbed by a rent boy, and as the police inspector in Le Doulos:

Here he is in Un flic as the homosexual art collector who has been robbed by a rent boy, and as the police inspector in Le Doulos:

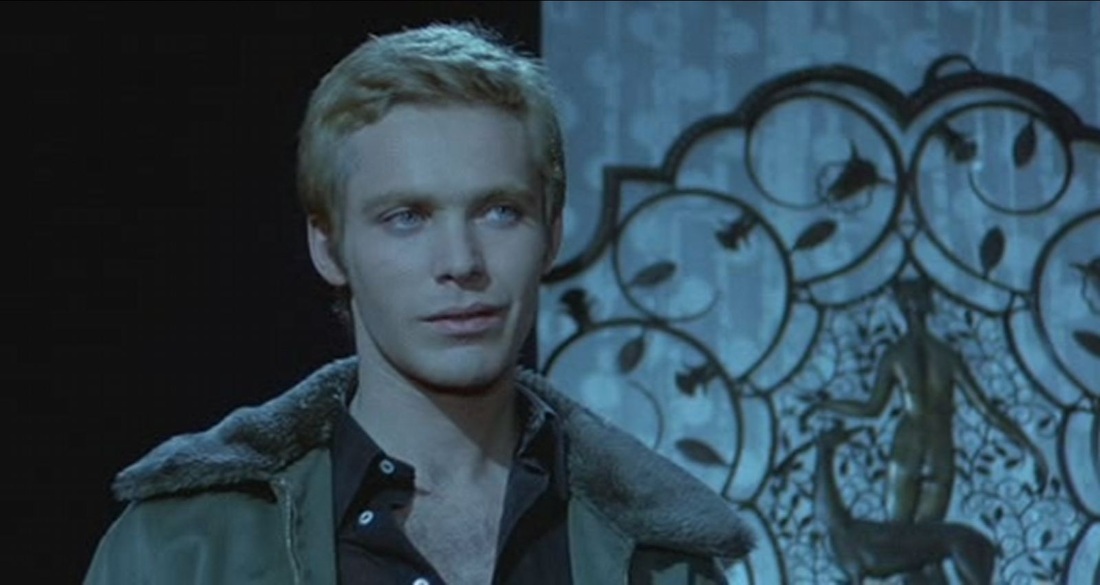

Incidentally, the rent boy is, with the drug trafficker denounced by the transvestite, one of two distinctly blonde males in Un flic (three counting the transvestite). They too, I would say, are a part of the backdrop of blondness against which Deneuve is staged:

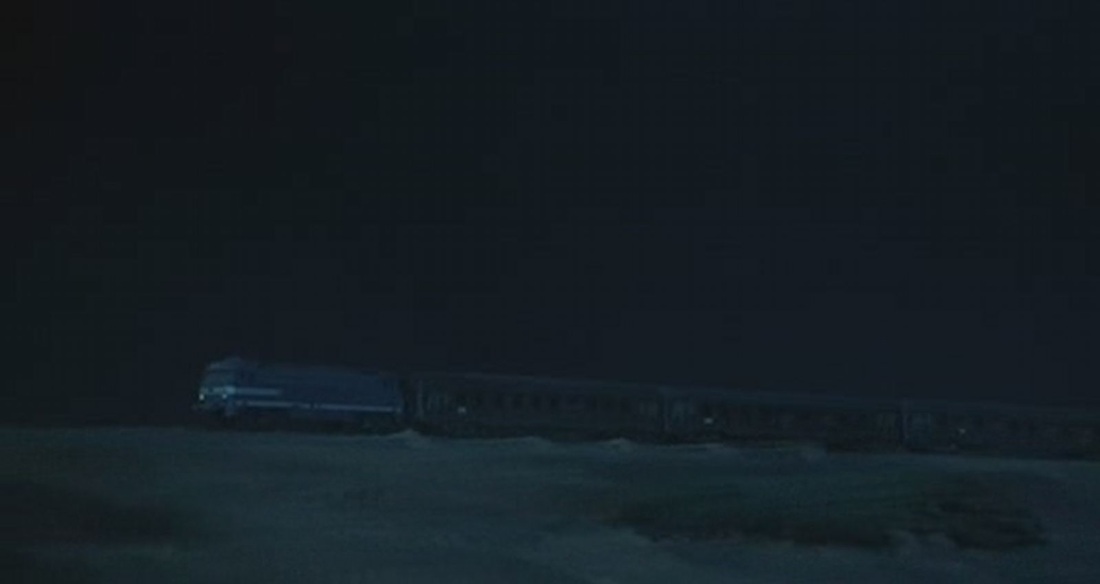

I hadn't meant to get distracted by cars, hats and hair colour. The prompt for this piece was the film's very peculiar shifts between renderings of the real world and artificial reconstructions of it. The example most often given in complaints about the film concerns trains. They are an important plot element and a recurrent background motif:

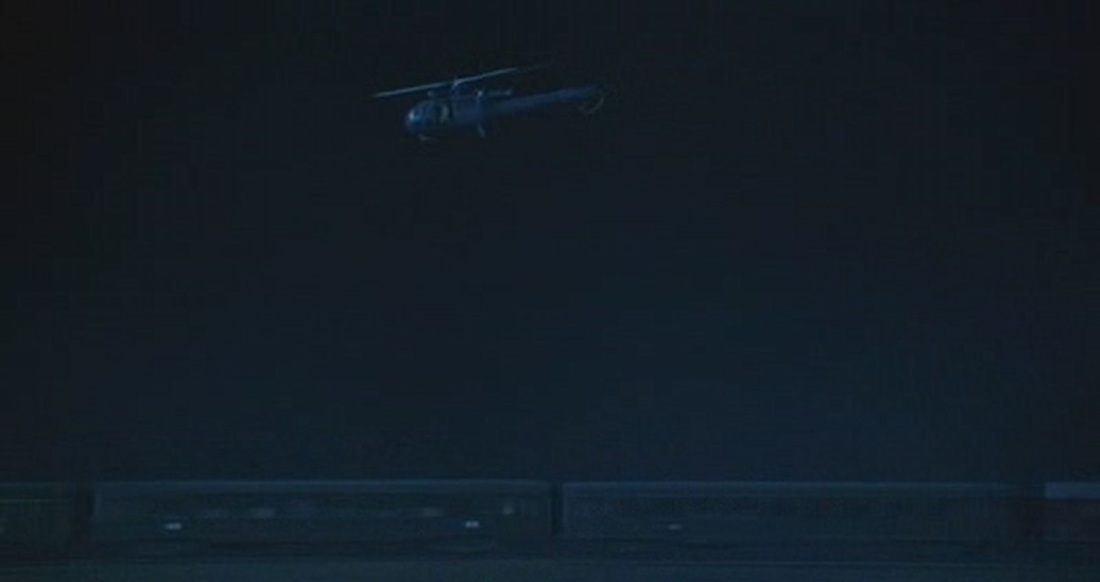

The most important of these is the last one, the Paris-Lisbon express, pulling into Bordeaux. In the next tranche of its journey it will be boarded from a helicopter by one of the gang who will steal a consignment of drugs being taken across the border. We see the train again during the heist, or rather we see a replica model of it, being followed by a replica model of a helicopter:

The close-up views of actual railway carriages and an actual helicopter only serve to make these models look more like toys, and it is hard to sustain, as I would wish to, an argument that this is self-conscious artifice. Ginette Vincendeau offers a persuasive defence:

'The ridicule poured on the use of models for this sequence is partly justified: train and helicopter do look like toys, even if they are, arguably, used with ironic self-consciousness - is Melville not acknowledging this when he cuts, at the end of the sequence, to a real helicopter dropping the men back at their starting point? Whatever the pros and cons of the models, the sequence on the train is of such fantastic precision and suspense that one forgives the defect. One is not surprised to hear that Melville may have spent "eight months editing the film".' - Ginette Vincendeau, Jean-Pierre Melville: an American in Paris, p.205.

'The ridicule poured on the use of models for this sequence is partly justified: train and helicopter do look like toys, even if they are, arguably, used with ironic self-consciousness - is Melville not acknowledging this when he cuts, at the end of the sequence, to a real helicopter dropping the men back at their starting point? Whatever the pros and cons of the models, the sequence on the train is of such fantastic precision and suspense that one forgives the defect. One is not surprised to hear that Melville may have spent "eight months editing the film".' - Ginette Vincendeau, Jean-Pierre Melville: an American in Paris, p.205.

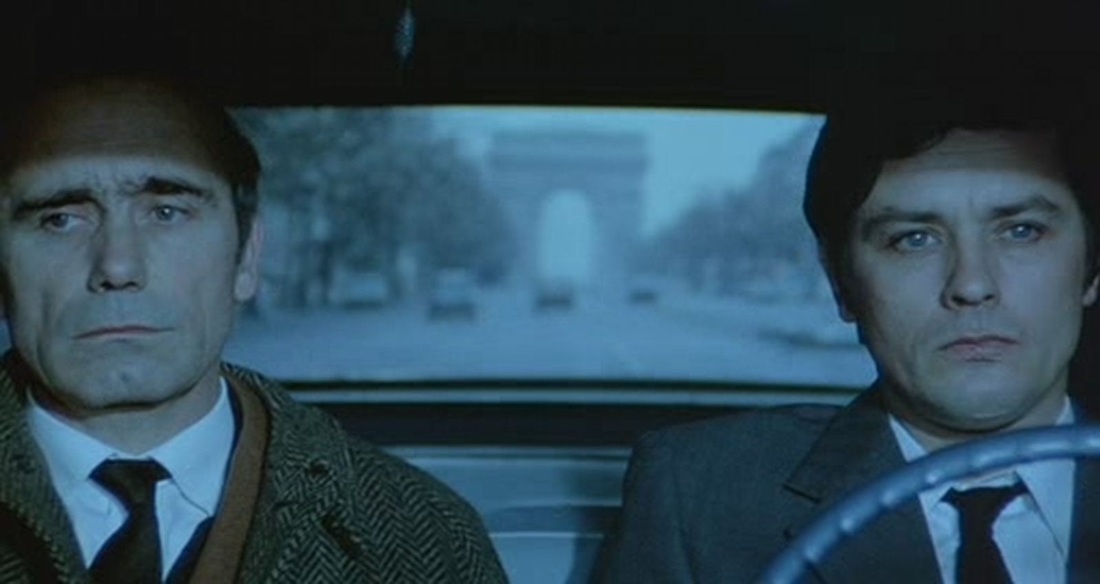

There is self-conscious artifice all the way through Melville's crime films, and its emblematic moment is the one where real world and reconstruction - location and studio - are combined in the same shot. Melville loves projecting the real streets of a city into the background of studio-simulated car rides. Here is an anthology of such signature moments:

This is the kind of procedure that the New Wave could dispense with by bringing its smaller cameras into the space of an actual car and from that space filming the actual world around it. When the procedure returns, in Godard's Alphaville and Pierrot le fou, it is to acknowledge the artifice and accentuate its formalism:

Whether Godard is being explicitly Melvillian here, the pretext for such studio confections in American cars (a Lincoln Continental and a Plymouth Valiant) is necessarily Melville.

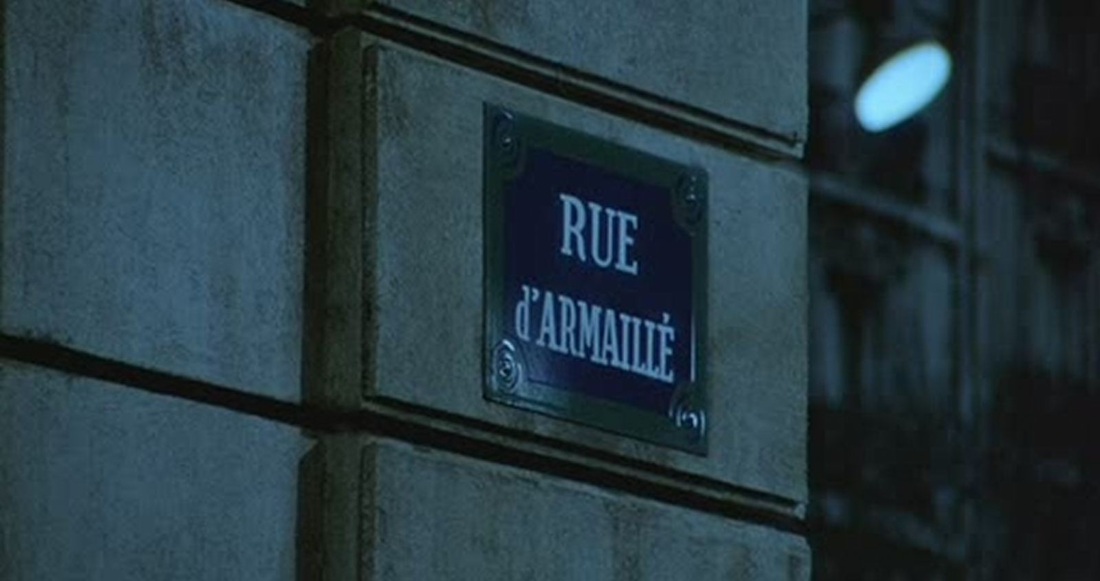

It was a different kind of studio confection involving a car that prompted this piece. A key location in Un flic is 'Simon's', the nightclub near the place de l'Etoile run by one of the bank robbers. The interiors of nightclubs are the kind of space Melville particularly enjoys reinventing in the studio. I haven't the space in this piece to digress on this topic, so shall stick to the nightclub's exterior:

The film is careful to give us the exact street, the rue d'Armaillé, in the 17e arrondissement, and from the view we are given of the avenue Carnot and the Arc de Triomphe beyond we can fix the address as number 1, just before the junction with the rue des Acacias:

The trees were in blossom on the avenue Carnot when the Google Maps image was taken (May 2008), hiding the Arc de Triomphe and making it harder to match this view with what we see in Un flic. We needn't be surprised that there is a boulangerie now where the nightclub was - things change, and also there never was a nightclub there, since the rue d'Armaillé in Un flic is a studio construction in front of a backdrop of the Arc de Triomphe. A pair of flashing lights on the avenue Carnot and a cyclist animate this otherwise static picture:

Ten years before, in Le Doulos, Melville had created the space outside a sophisticated Paris nightclub by putting an awning over the entrance to his rue Jenner studios (see also here):

In the fiction of Le Doulos this club has no specified location. The difference in Un flic is the need to situate the nightclub near the location of the film's dénouement, at the top of the avenue Carnot by the Arc de Triomphe. This topographical exigency is what, paradoxically, determines the reconstruction of the rue d'Armaillé, the avenue Carnot and the Arc de Triomphe in the studio. This one composition connects Simon's club with the eventual place of his death, in the shadow of the Arc de Triomphe:

When Un flic approaches the moment of Simon's death, the Arc de Triomphe is shown only partially, or framed, or reflected, or as back-projection - in each case diminishing its triumphalism and echoing the facticity of its first representation as backdrop:

The sequence outside Simon's nightclub with the Arc de Triomphe as backdrop brings the half-kilometre-long avenue Carnot into the restricted space of the rue Jenner studio. At the same time Melville plays with the actual space of the studio when he has the cyclist come from around a corner to the left of the set, as if he had also reconstructed here the rue des Acacias:

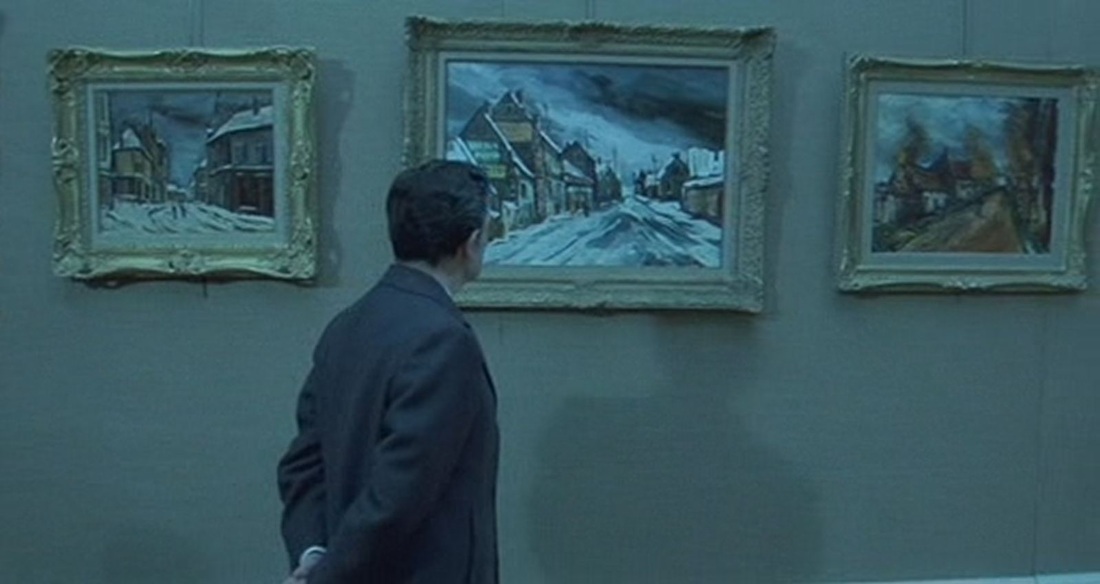

The artifice in this staging of cityscape is foregrounded by association with art, as the following sequence opens on a close-up of a village street by Vlaminck:

Melville's composition matches Vlaminck's, and as the camera pulls away from the painting we find ourselves in a studio-constructed space that matches that of the nightclub exterior:

The group to the right have just come from around a corner, like the cyclist in the previous sequence. The backdrop replacing the Arc de Triomphe represents the Louvre's Grande Galerie:

Hubert Robert had also portrayed the Grande Galerie as an ancient ruin (see here). Melville's version of the Louvre is not as fanciful, but is quite unfeasible. Next to the first Vlaminck are two other Vlamincks, though Vlaminck would never have been exhibited in the Louvre:

The painting to the left is 'Epernon, paysage d'hiver', from 1927; to the right is 'La Route', from 1905. I haven't been able to identify the one in the middle.

Melville puts other paintings in the Louvre that I cannot identify. In the corner are some marine subjects - if you can identify any please let me know, here:

Melville puts other paintings in the Louvre that I cannot identify. In the corner are some marine subjects - if you can identify any please let me know, here:

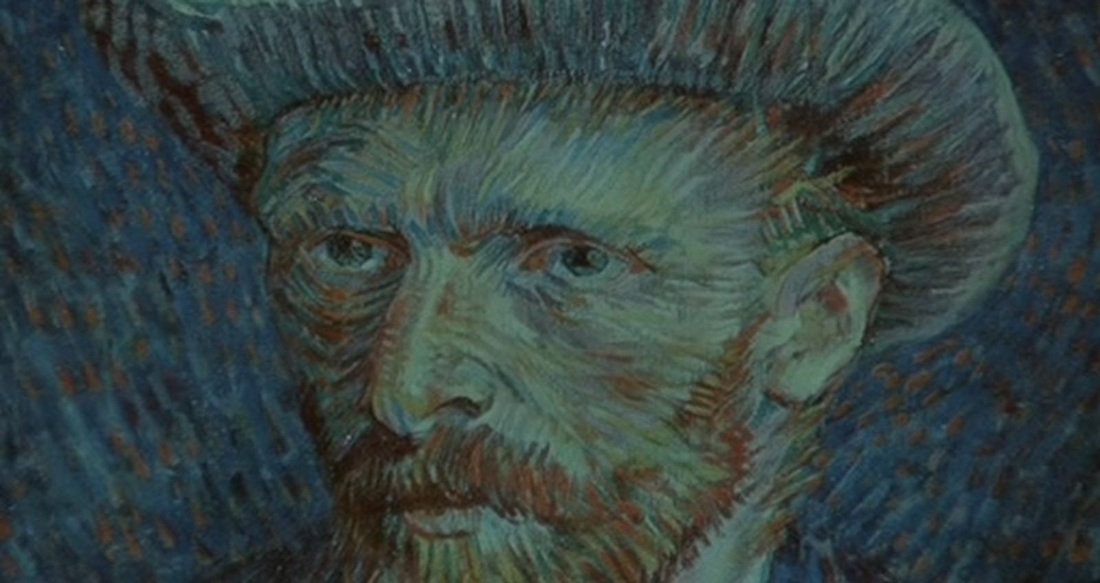

On the other hand, the pictures on the opposite wall are much easier to identify:

Simon is standing in front of Van Gogh's Wheatfield with Cypress, the one in New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, I think. The Van Gogh portrait with a bandaged ear is privately owned. The painting at the right edge is his portrait of Patience Escalier, also privately owned.

The sequence ends with Simon, in a felt hat, in vis-à-vis with Van Gogh in a felt hat, from the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam:

The sequence ends with Simon, in a felt hat, in vis-à-vis with Van Gogh in a felt hat, from the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam:

This simple artifice, a match of hats across time, combines the inter- and intra-textualities typical of Melville with another characteristic combination: pathos and humour.