place as indicator of time in Zola's Thérèse Raquin (1867)

There are no dates in Zola's novel. Precise markers of time position events relative to other events in the novel, but nothing tells us when exactly those events occur. Chapter One says that 'a few years ago' there was a shop in the passage du Pont-Neuf with a sign that read 'Thérèse Raquin', and describes Thérèse with her aunt and her husband Camille in the shop. Chapter Three describes three years of life in this place, with Camille never missing a day of work and Thérèse suffering daily tedium and emptiness. Her affair with Laurent covers about ten months before they murder Camille. Laurent and Thérèse marry almost two years after the murder. About four months after the wedding Laurent leaves his job and rents a studio in which to paint. Further events are separated by a few months, and the climax, when each has resolved to kill the other, comes about seven years after the Raquin family moved to Paris. If we took the time of publication as the time of narration, the latest date possible for the move to Paris would be 1860.

The chronology of Zola's novel is vague; its topography, on the other hand, is precise.

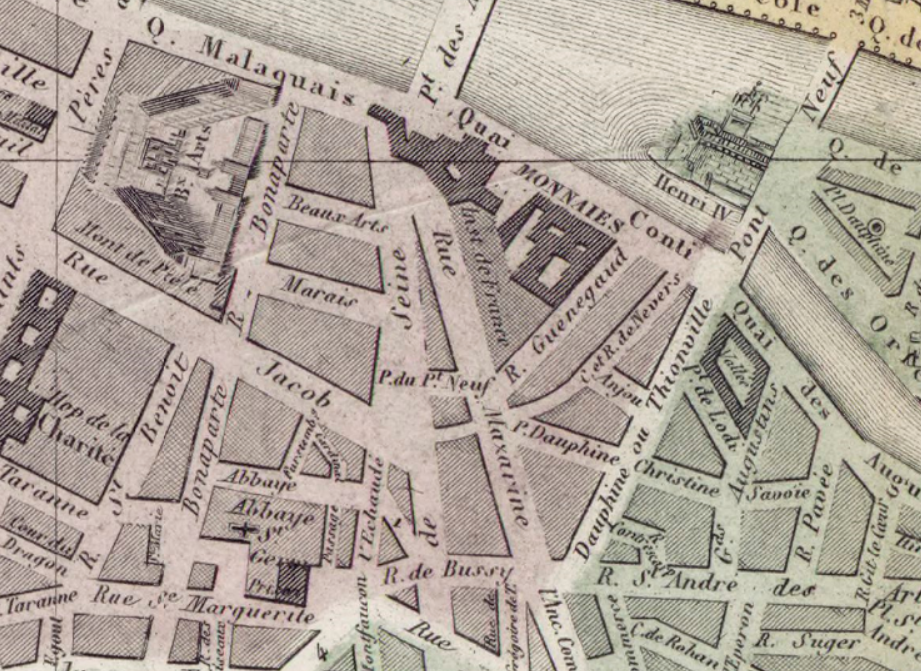

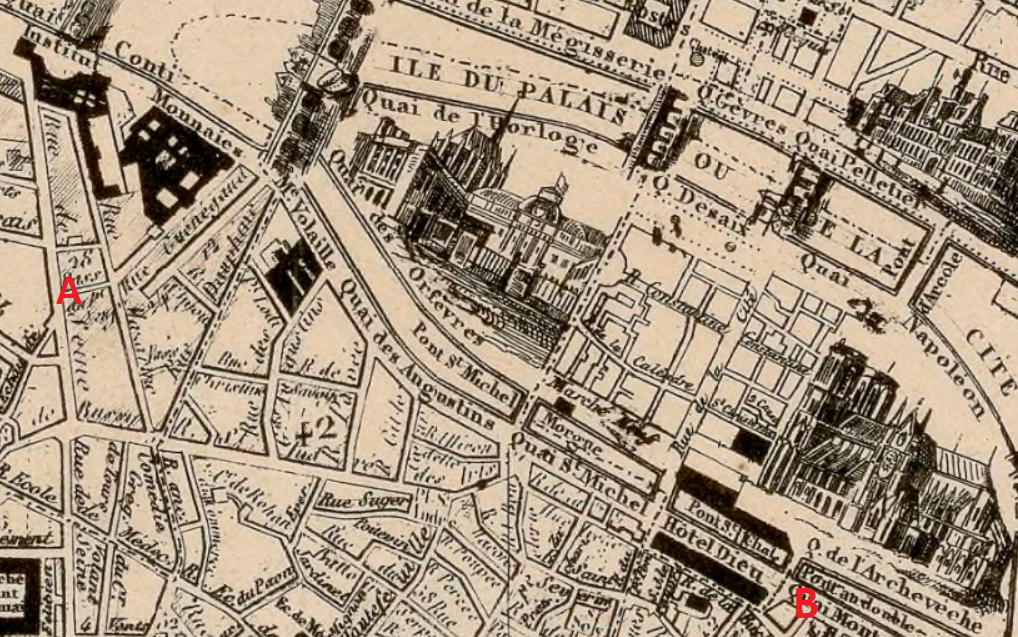

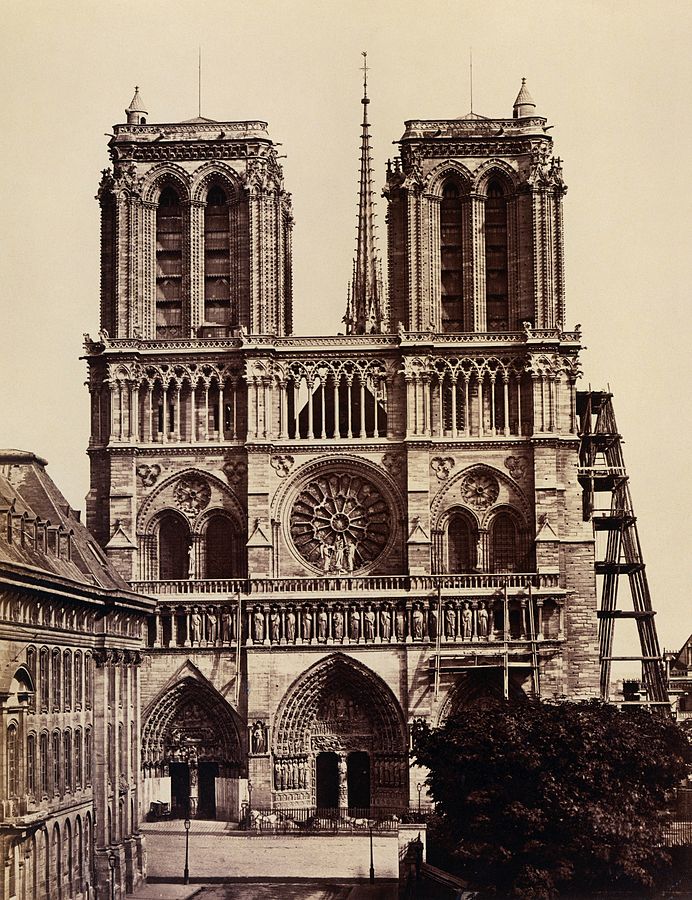

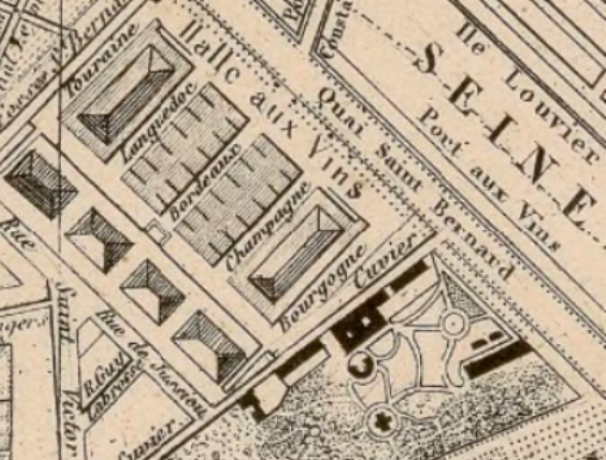

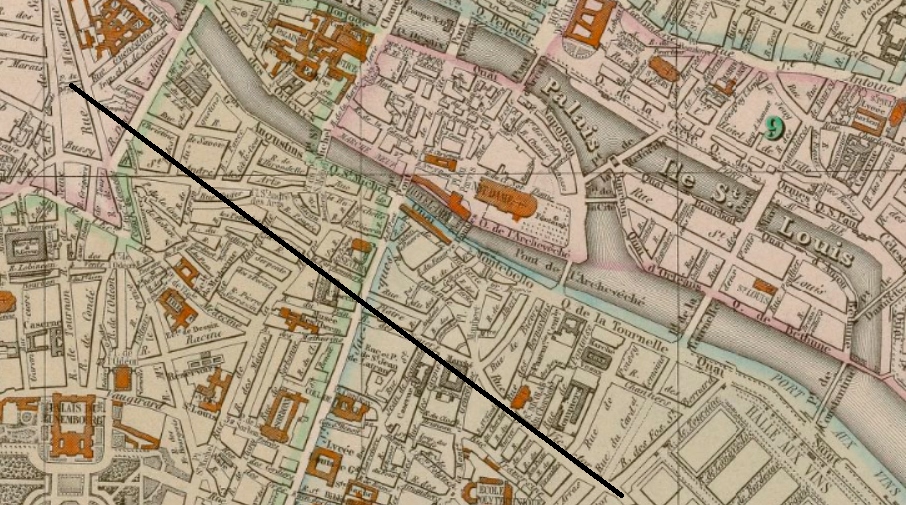

The passage du Pont-Neuf is the starting or end-point of several journeys across Paris, beginning with Camille's daily walks from home to work and back. He sets out from home (A on the map below), walks down the rue Guénégaud to the quais and follows these east, stopping (at B) to contemplate the scaffolding around the cathedral of Notre Dame, which was being restored:

The restoration of Notre Dame was ongoing through the 1850s and 1860s, so this mention isn't a precise indicator of time. Here are two photographs showing scaffolding on the cathedral, from 1860 and 1862:

Camille's walk to work continues past the Port aux Vins; on the way back from the offices of the Chemin de fer d'Orléans he spends time in the Jardin des Plantes contemplating the bears:

Camille's itinerary along the quais is replicated by his friend and eventual murderer Laurent, firstly in visiting the Raquin household as a guest and then, when he has replaced Camille as Thérèse's husband, in going from the passage du Pont-Neuf to his place of work, the same as Camille's. This replication is facilitated by Zola having placed Laurent's initial domicile on the rue Saint-Victor, 'opposite the Port aux Vins', i.e. in the same general area as the railway company offices, so that Laurent's journey from his home to the Raquins' home is, like Camille's, along the quais. Technically Laurent's home on the rue Saint Victor is opposite the Halle aux Vins, the Port being on the river, by the quai Saint Bernard. Zola's manipulation of the topography through nomenclature heightens the impression that Laurent's route necessarily matches that taken by Camille, along the river, whereas actually Laurent's itinerary could have been more direct, for example, down the rue Saint Victor to the place Maubert, along the rues Galande, Mâcon and Saint André-des-Arts to the rue Mazarine and up to the passage du Pont-Neuf:

The itineraries of Camille and Laurent along the river add to the novel's supply of aquatic motifs, the most dominant of which is the river itself.

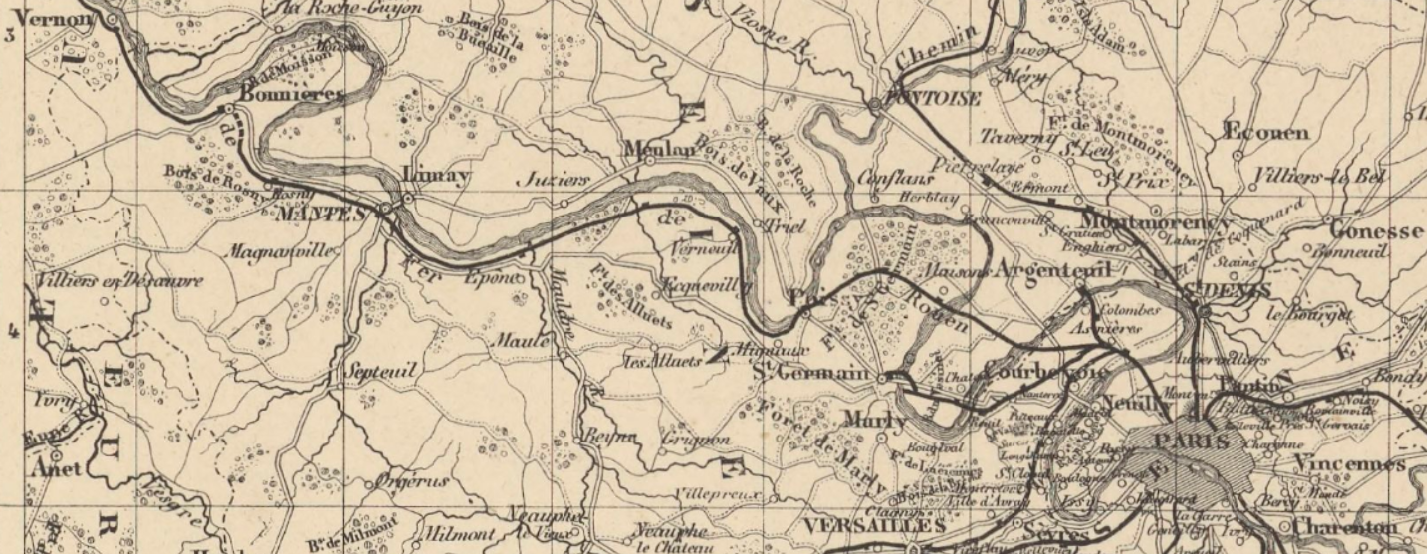

Camille and Thérèse were brought up by the Seine at Vernon, they move to an address in Paris near to and named after a bridge over the Seine, Camille walks along the Seine to and from work every day, he is murdered by being thrown into the Seine at Saint Ouen, his body spends fifteen days disintegrating in the Seine to end up on a slab at the Morgue, situated on the Ile de la Cité, overlooking the Seine.

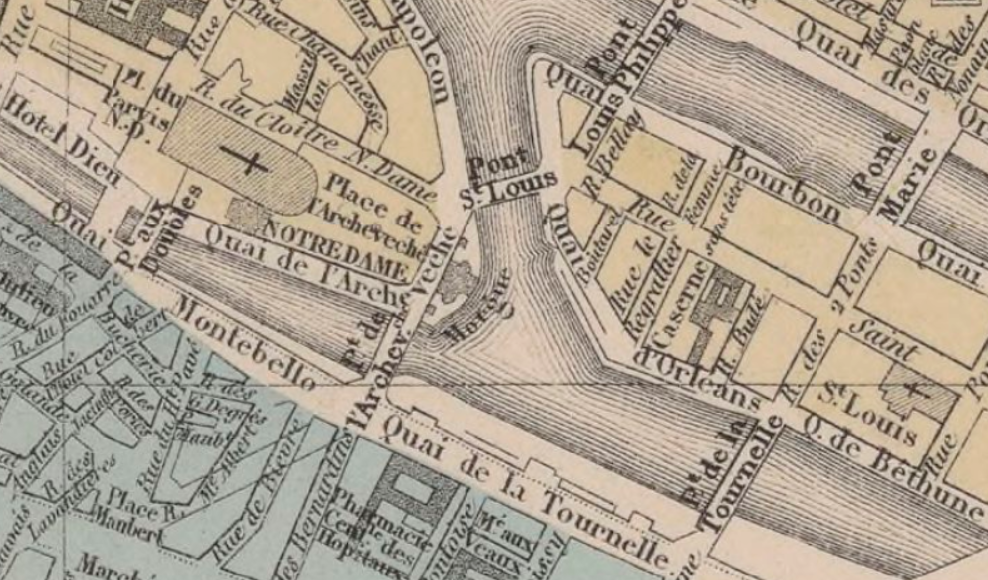

The exact location of the Morgue in Thérèse Raquin depends on when exactly the novel is set. Until 1864 the Morgue was on the quai du Marché Neuf, just east of the Pont Saint Michel, then it moved to a building by the Place de l'Archevêché:

If the Raquin family moved to Paris in 1860, the latest date at which they could have done so, at a stretch the Morgue to which Camille's body is taken almost four years later could be the new Morgue, above right. For reasons that I shall give below, I think the Morgue in Thérèse Raquin must be the earlier one, above left.

The excursion to Saint Ouen would have begun with Mme Raquin seeing off Thérèse, Camille and Laurent from the end of the passage du Pont Neuf: 'she would kiss them as if they were setting out on a voyage' (Ch. XI). The voyage motif was introduced earlier when Laurent asked Thérèse if they couldn't get rid of Camille for a while: 'Can't you send him on a voyage, somewhere far away?' [...] 'Do you think a man like that would agree to go on a voyage?... There's only one voyage you don't come back from...' (Ch. IX).

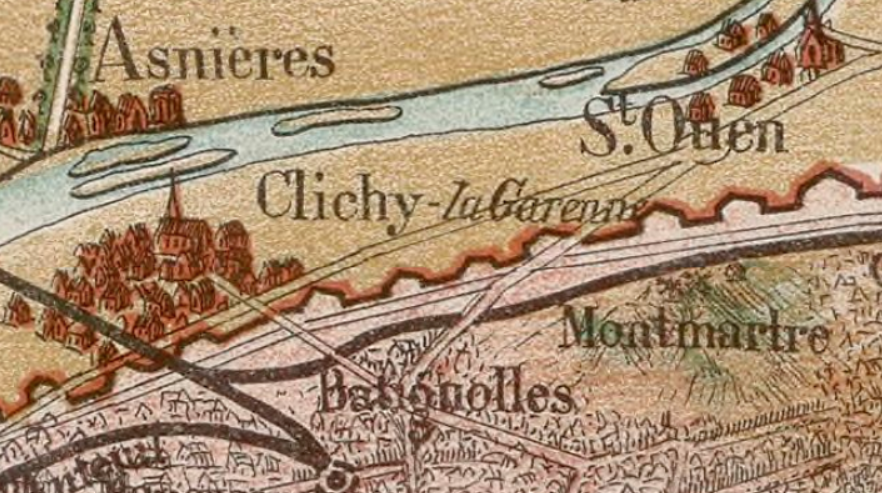

The group take a cab as far as the fortifications and then walk to the river at Saint Ouen:

The logical exit through the fortifications is the Porte de Saint Ouen (the route heading east from Batignolles, on the map above). Laurent's return journey, after the murder of Camille, takes him by 'voiture publique' to the terminus at the Barrière de Clichy (south-east of Batignolles), from where he took a cab. I think that the omnibus went via Clichy, so would enter Paris through the Porte de Clichy.

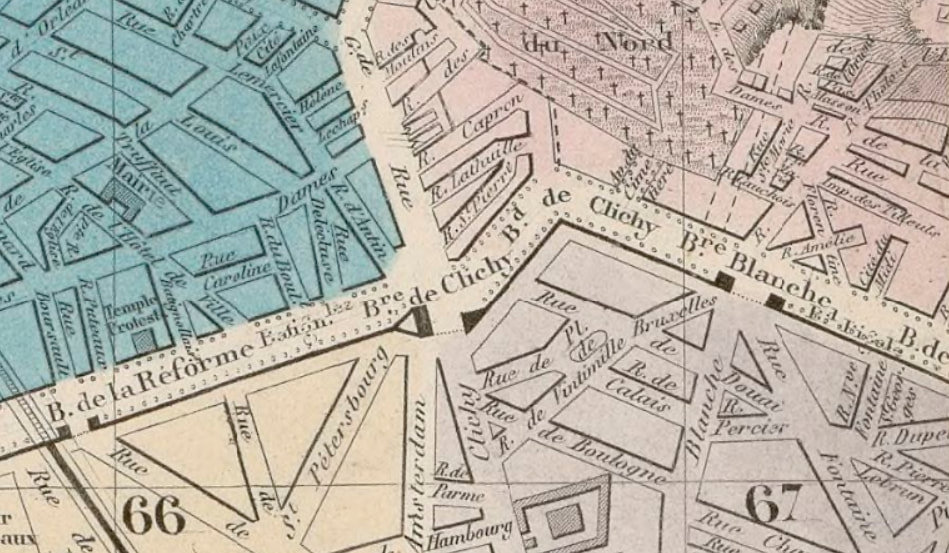

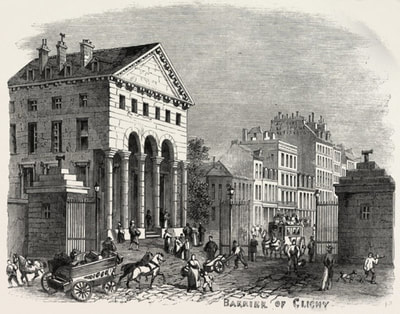

The Barrière de Clichy is another marker of time in the novel. This octroi (customs-house) was situated at what is now the Place de Clichy:

The Barrière de Clichy is another marker of time in the novel. This octroi (customs-house) was situated at what is now the Place de Clichy:

Here is Gustave Le Gray's photograph of the barrier, taken from his studio in the 1850s, with a 1859 illustration in which we see an omnibus like that taken by Laurent arriving from Saint Ouen:

In 1860 began the demolition of the customs-house:

And by 1861 it was no longer being mentioned on maps. Zola's mention of it in narrating Laurent's return from Saint-Ouen seems to date the murder to 1860 at the latest, moving back the whole chronology I suggested above, so that Camille, Thérèse and Mme Raquin will have moved to Paris no later than 1856. Of course the name 'Barrière de Clichy' might have persisted in usage after the demolition of the customs-house itself, even with reference to the destinations of buses. I wouldn't say that this location conclusively indicates a date for the setting of Thérèse Raquin.

I do, however, find conclusive the evidence around another location mentioned, this time as part of an itinerary within Paris. Close to the end of the narrative, when relations between Thérèse and Laurent are close to terminal, Thérèse takes to leaving the house for hours on end, arousing Laurent's suspicions that she might be planning to go to the police and denounce him as a murderer. Eventually he follows her, and immediately panics when she turns into the rue de l'Ecole de Médecine, because he knows that somewhere nearby is a police station. She in fact goes to a café at 'the former Place Saint-Michel', on the corner with the rue Monsieur-le-Prince. There she meets friends, drinks absinthe and eventually leaves with a young man, going via the rue de La Harpe to a house on the rue Saint-André-des-Arts:

Thérèse's itinerary is easy to reconstruct. She turns right from the passage du Pont-Neuf into the rue Mazarine, crosses the carrefour de Buci into the rue de l'Ancienne Comédie, turns left into the rue de l'Ecole de Médecine then right into the rue de la Harpe up to a café on the place Saint-Michel. From there, she and her lover go down the rue de la Harpe to reach the rue Saint-André-des-Arts. The Haussmannian changes that the place Saint Michel was about to undergo fix the date of this episode at no later than 1860. The illustration below, dated 1860, shows the demolition of the place Saint Michel, and on Vuillemin's 1860 map the name of the place has gone and the rue de la Harpe no longer reaches that far, curtailed by the laying out of the boulevard de Sebastopol (later renamed boulevard Saint-Michel):

So if Thérèse starts to go about town in 1860, the date of the Raquin family's move to Paris from Vernon must be c. 1853.

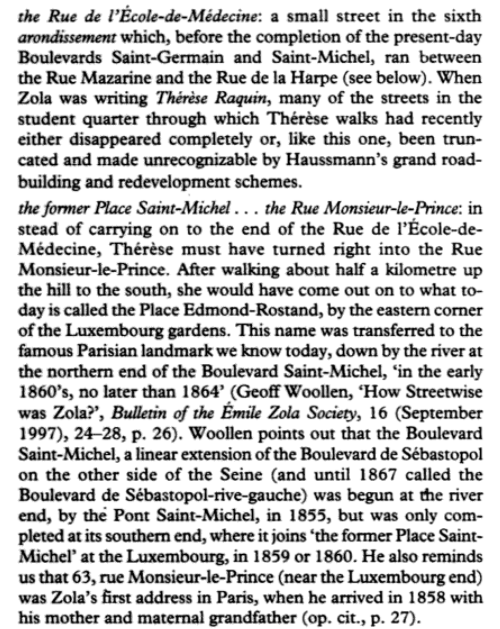

Most of these conclusions regarding what topography tells us about chronology in Thérèse Raquin had already been arrived at by Geoff Woollen in 1997 ('How Streetwise was Zola?', Bulletin of the Emile Zola Society, 16), and I might have saved myself some trouble if I had read Geoff's piece before trying to work all of this out. In the explanatory notes to his translation of the novel (Oxford World's Classics, 1998 [second edition]), Andrew Rothwell make good use of Woollen's research, though I disagree slightly with Rothwell as to the detail of Thérèse's itinerary:

I think Thérèse must have reached the place Saint Michel via the rue de la Harpe, rather than the rue Monsieur-le-Prince.

Only topography gives us anything like an exact sense of the novel's chronology, and that is because the topography of Paris in the 1850s and '60s is in flux, changing over time. These changes are the city's history, and their feint traces in the novel are almost the only traces there of history tout court. When we are told that Camille sought to educate himself by reading Thiers's Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire (begun 1845 and at volume 14 by 1856) and Lamartine's Histoire des Girondins (1847), we may conclude that history is of interest only to Bovaryesque imbeciles (Camille as a reader is clearly modelled on Flaubert's Charles, just as Thérèse as a reader is modelled on Emma). Zola's reader would probably make a connection between the revolutionary period covered by Lamartine (1791-1794) and Lamartine's own role as a revolutionary politician in 1848, and would probably connect the passage from Republic to Empire in 1804 as related by Thiers to the passage from Republic to Empire instigated by Louis-Napoleon in 1852, but the novel says nothing about the politics of the present in which the drama is set, nor about the immediate political past. The contrast with Zola's approach to history and politics in the Rougon Macquart cycle is striking.

History of a sort is evoked in the account of Thérèse's origins. She was born in Oran, to a North African mother. Her father, Captain Degans, was a soldier fighting in France's wars of colonial expansion in North Africa. Thérèse was twenty-one when she married Camille, the latest date for which must be 1853, which would mean she was born at the latest in 1832. France's occupation of Algeria began in July 1830, and Degans's liaison with Thérèse's mother - the daughter of an African tribal chief, Thérèse was told - soon followed. We are told that, after depositing the two-year-old Thérèse with her aunt, Degans returned to Africa and was killed there a few years later. It would be reasonable to conclude that he died in the course of General Bugeaud's campaign against Abd-el-Kader, 1836-37. Here again, history is manifest only obliquely, subordinated to the thematisation of Thérèse as racial other.

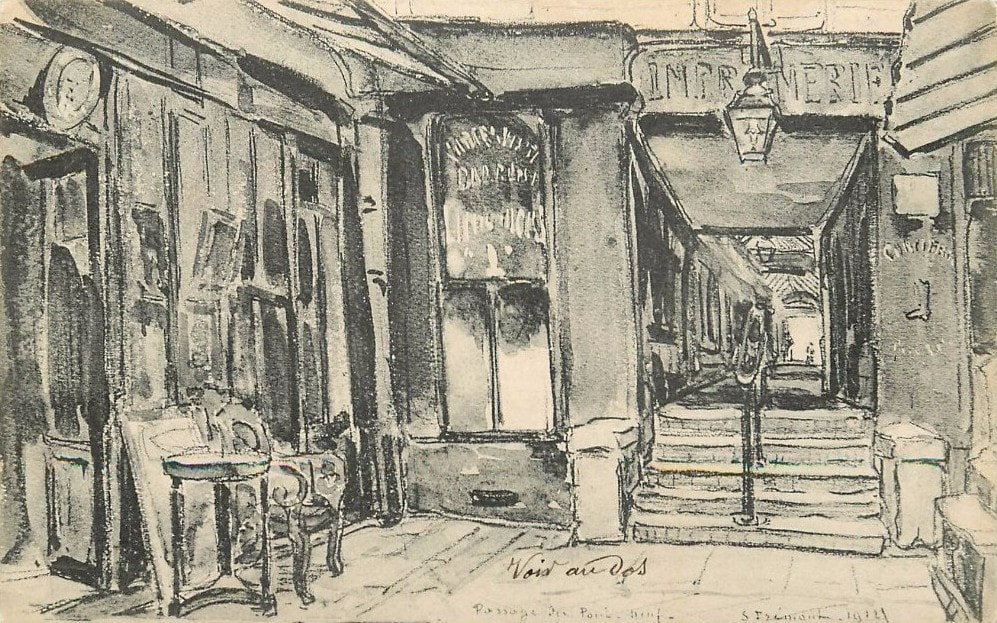

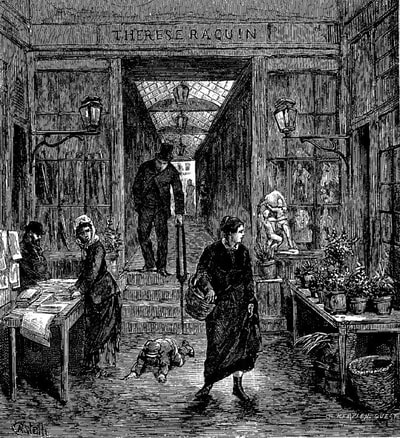

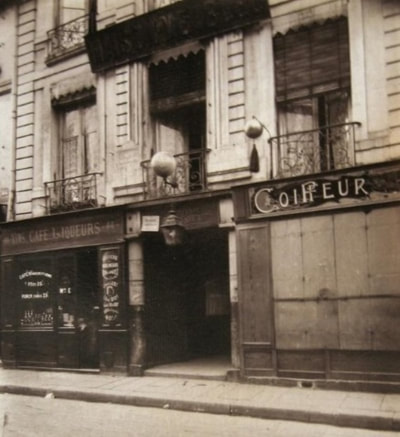

Appendix 1: le passage du Pont-Neuf

In his famous letter to Zola (June 10 1868), Sainte-Beuve challenged his representation of the passage du Pont-Neuf: 'I know this passage as well as anyone and for all the reasons a young man might have had to go wandering there. Well, it's not a true description, it's fantastic, it's like Balzac's rue Soli. The passage is plain, banal, ugly and above all narrow, but it doesn't have that profound blackness and Rembrandtesque tones you accord it.'

In 1879 Zola commented on Sainte-Beuve's criticism: 'He's right, only, it must be accepted that, simply, places have the sadness or the gaiety that we bring to them; we shudder when we pass a house where a murder has just been committed, though the day before it had seemed banal.'

In 1879 Zola commented on Sainte-Beuve's criticism: 'He's right, only, it must be accepted that, simply, places have the sadness or the gaiety that we bring to them; we shudder when we pass a house where a murder has just been committed, though the day before it had seemed banal.'

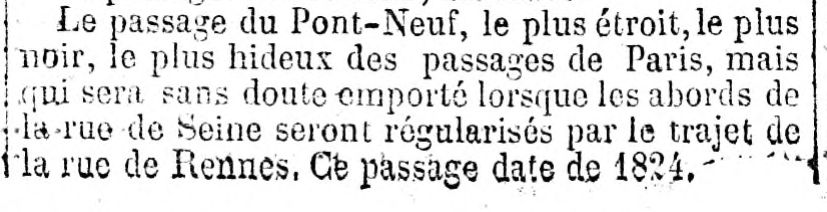

Contemporary comments on the aspect of this passage suggest that Zola could have been more forceful in his defence. In November 1868 an article on 'Les Passages et Galeries de Paris' in Le Petit Journal described it as 'the narrowest, the blackest, the most hideous passage in Paris'; in 1874 Pierre Larousse's Grand Dictionnaire, article 'Passages', said it was so dark that 'at midday you couldn't see a thing'.

It is quite possible, of course, that each of these descriptions was itself influenced by the description in Thérèse Raquin, but in 1850 a character in Xavier de Montépin's Confessions d'un bohème is described traversing 'that narrow and grimy corridor known as the passage du Pont-Neuf':

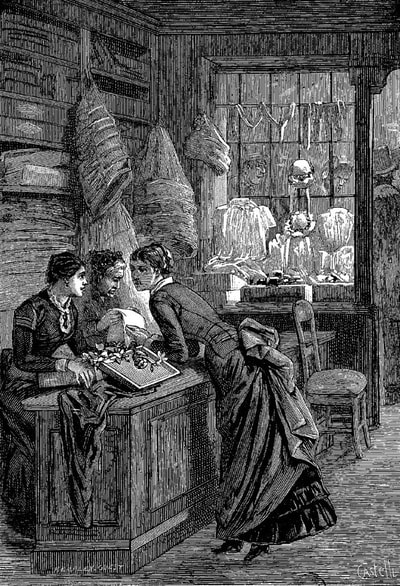

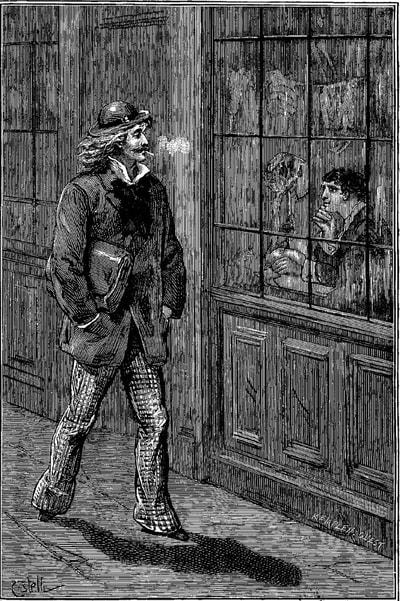

What visual record I can find of the passage du Pont-Neuf post-dates Zola's novel. Horace Castelli's illustrations for an 1883 edition of Thérèse Raquin correspond to Zola's depiction, of course:

Atget photographed the passage between 1910 and 1913, just before and in the course of its demolition:

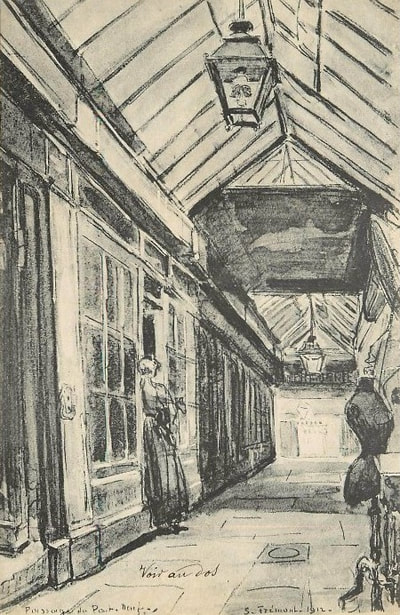

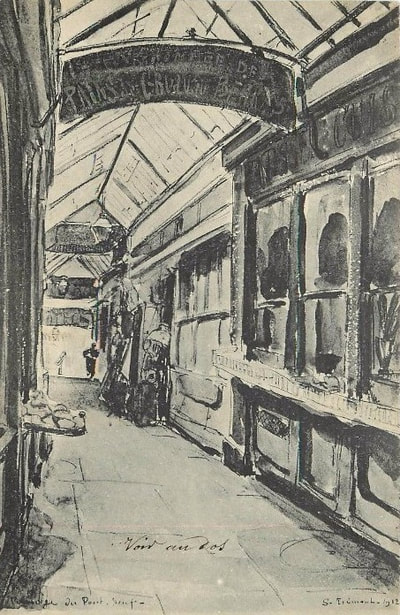

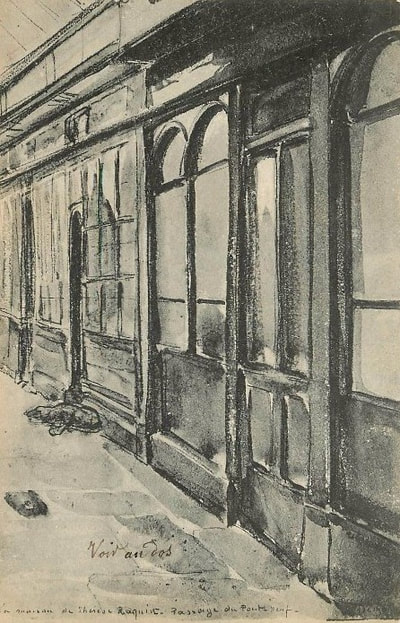

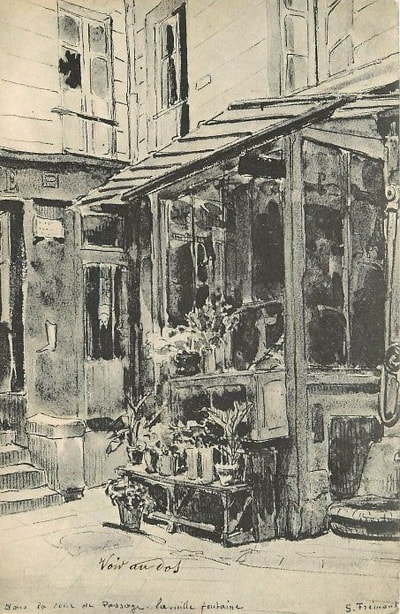

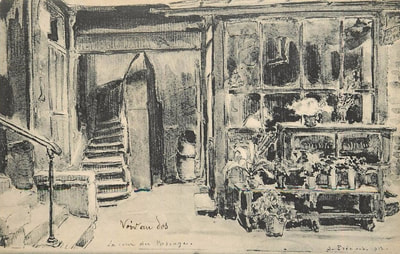

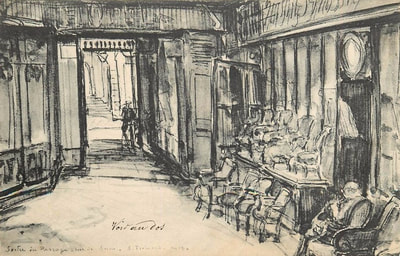

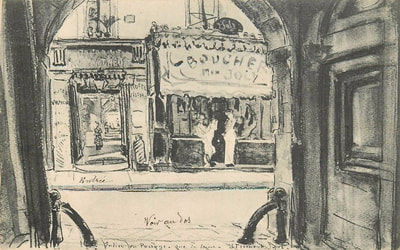

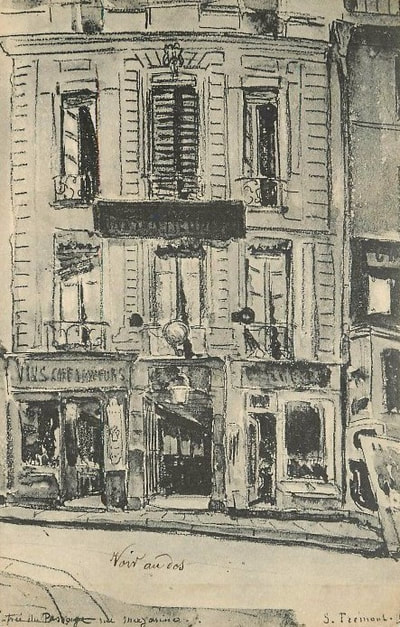

In June 1912 Suzanne Frémont recorded the passage just before its demolition in a series of drawings:

Appendix 2/ impressions of Saint-Ouen

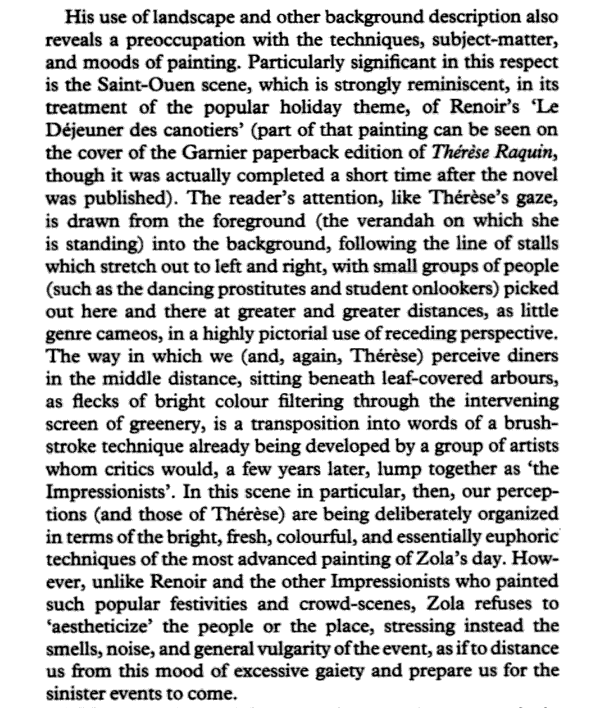

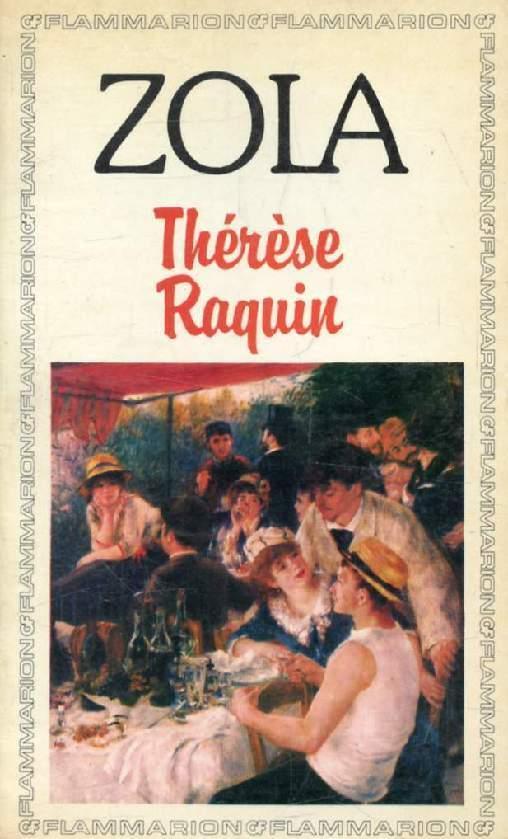

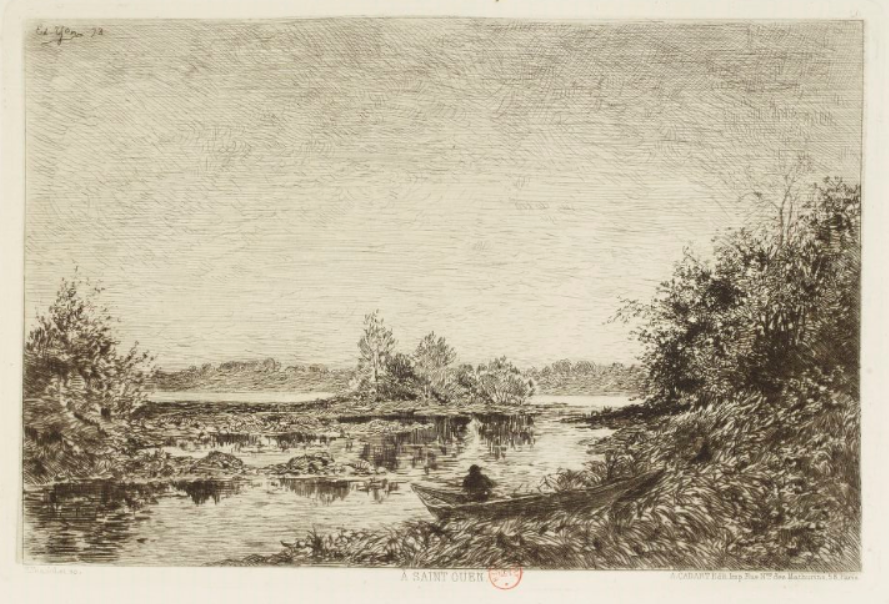

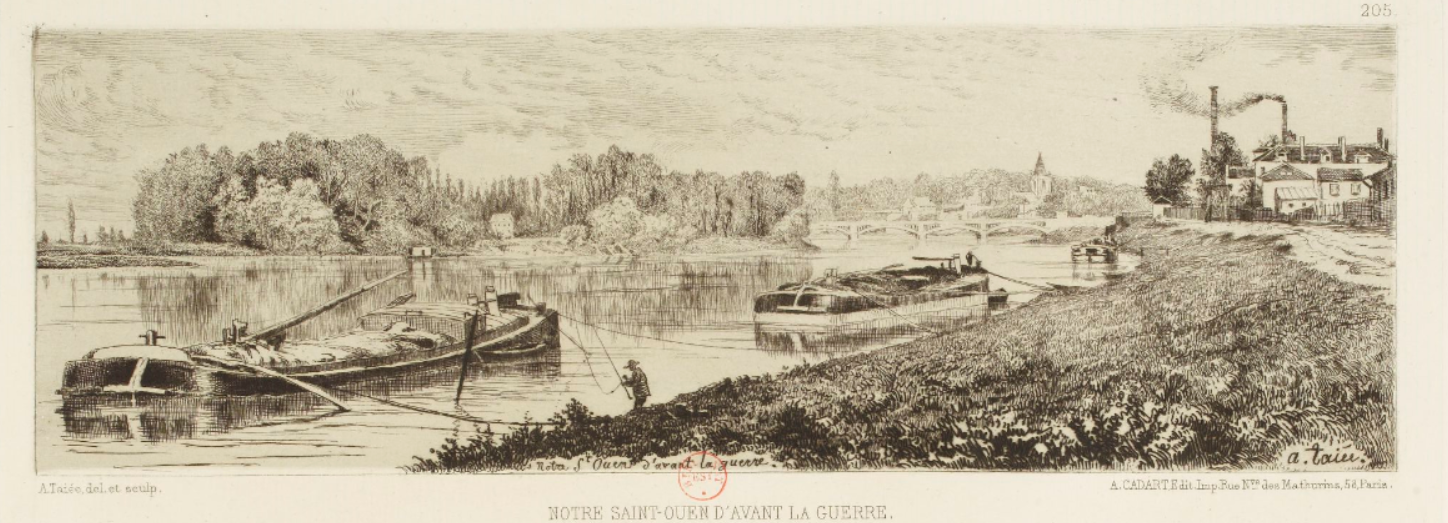

Whereas the novel's precise urban topography can be read map in hand, the excursion out of the city to Saint-Ouen is less precise, cartographically. After stating exactly how they got there - walking up the chaussée de Saint-Ouen from the fortifications - the novel presents the various elements of the setting - river, islands, woods, restaurants - more as impressions. Andrew Rothwell's excellent introduction to his translation of the novel relates Zola's approach directly to the practice of Impressionist painters:

|

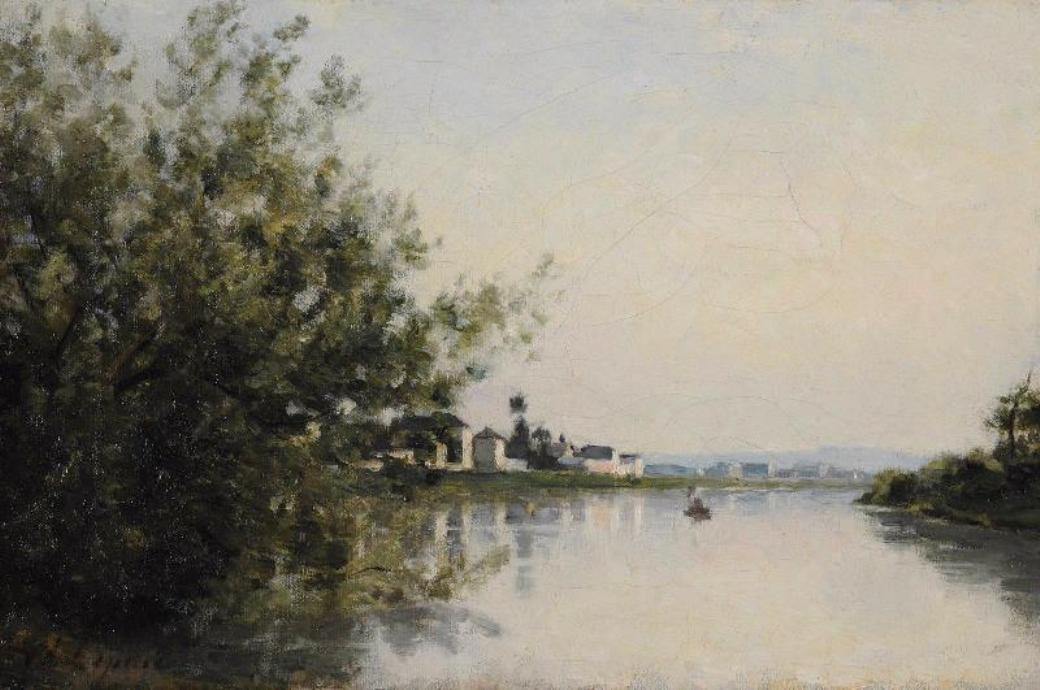

Renoir's Déjeuner des canotiers (1881) represents a scene at Chatou, further along the Seine to the west. Though several painted at Asnières, the other habitual destination for the Raquins' outings, no Impressionist painters actually seem to have recorded their impressions of Saint-Ouen. The green islands of Saint-Ouen remind Thérèse of her childhood in Vernon; paradoxically, several Impressionist painters, especially Monet, did depict Vernon and environs. |

The Rubenesque depiction of fishing at Saint-Ouen by Zola's friend Manet is hard to match up with the depiction of Saint-Ouen in Thérèse Raquin:

Here, from Manet and the Family Romance (2001, p.72), is Nancy Locke's comment on the location in this painting:

Better matches to Zola's depiction can be found in the work of other contemporaries:

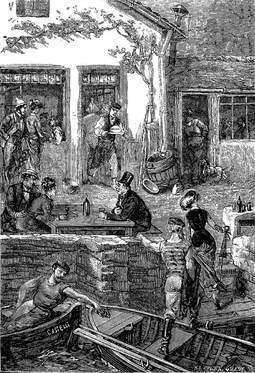

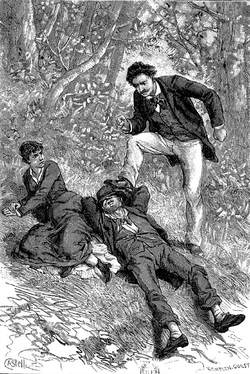

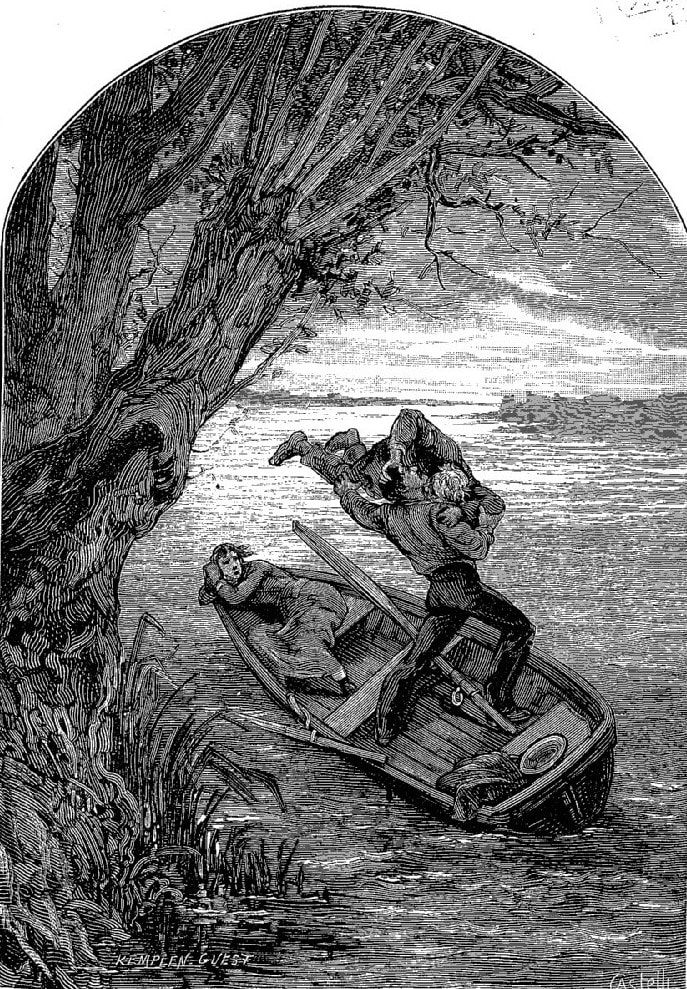

Three of Castelli's 1883 illustrations for Thérèse Raquin relate to the Saint-Ouen episode: