the Grisbi connection: Chabrol & Becker

|

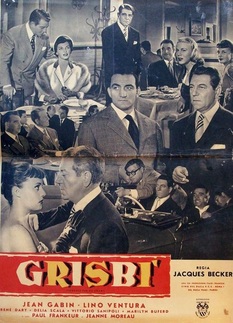

(The research for this post began with my looking at and for two streets from the opening sequences of two films, Claude Chabrol's Les Bonnes Femmes (1960) and Jacques Becker's Touchez pas au grisbi (1954), films that are linked by the word 'grisbi', but not by much else. This vis-à-vis of New Wave and pre-New Wave informs the discussion of several other films that feature in this post, mostly from between 1950 and 1960. I have tried not to be too distracted by interesting things that turned up in the process of investigating these streets, but possibly I haven't tried hard enough.)

|

1/ 22 rue Quentin Bauchart, 8e

The opening of Les Bonnes Femmes contrasts two Paris monuments, the Arc de Triomphe, with its flame to the unknown soldier, and the colonne de Juillet, with its statue of the Spirit of Liberty - one to the west of the city, the other to the east:

Views of the place de la Bastille and the avenue des Champs Elysées further establish the east-west reach of the film's topography before a right-to-left pan takes us from the Champs Elysées towards the first place of action, the rue Quentin Bauchart:

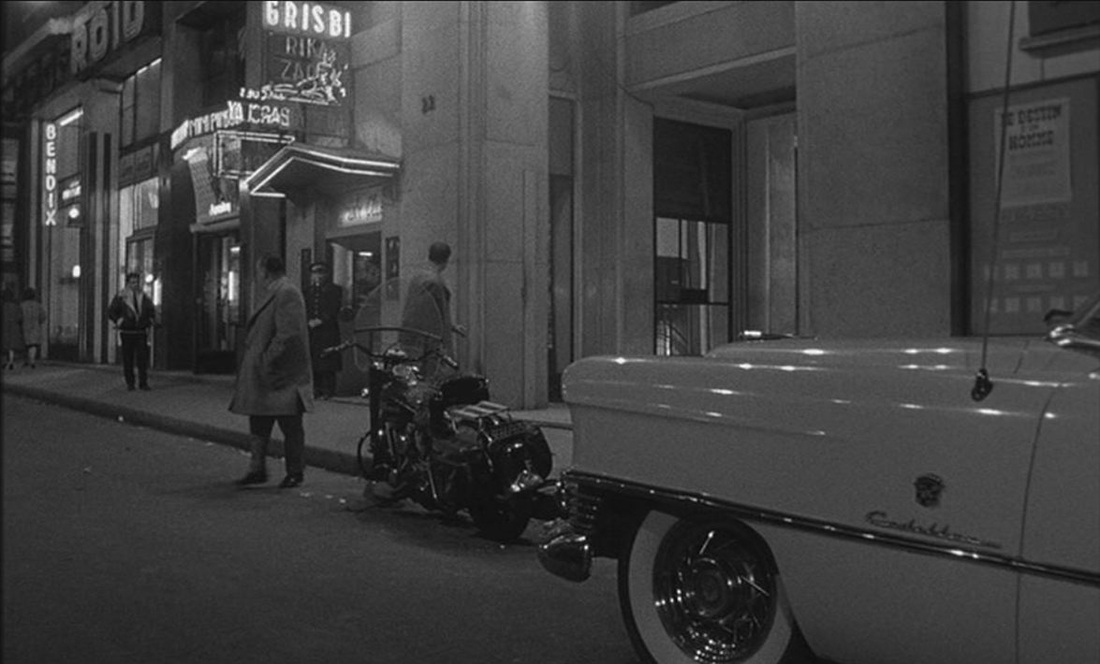

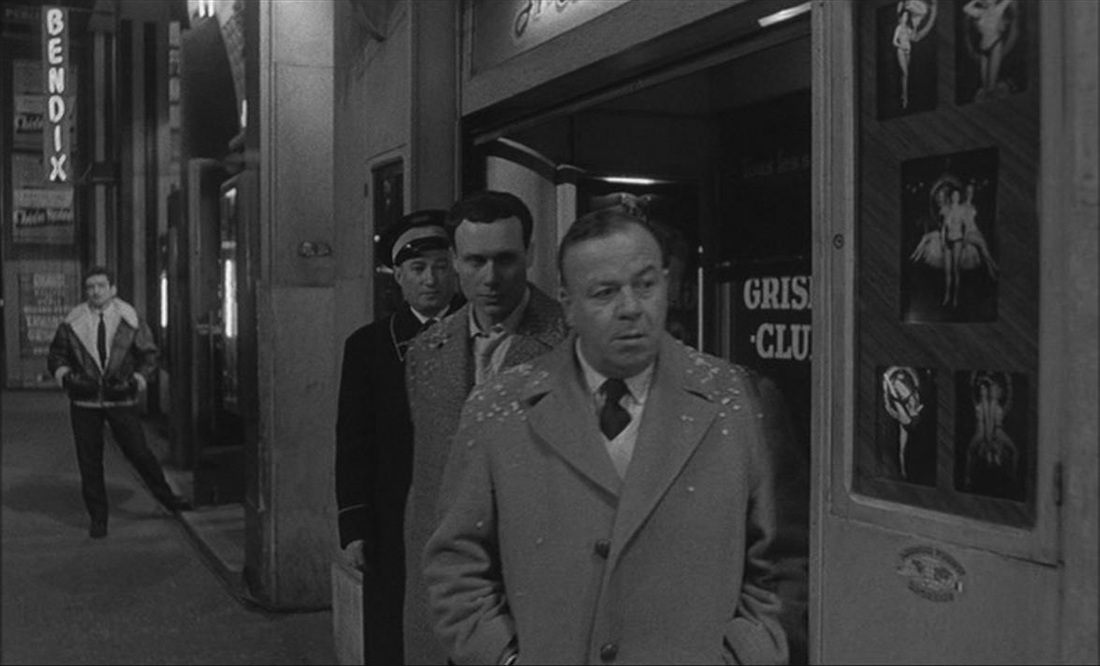

By the twenty-first of this sequence's thirty-six shots (note) the principal parties to the narrative that follows have come together on this street, neatly aligned in a composition characteristic of the film:

Two men on the pull ('dragueurs') are near the middle, half way up, having just emerged from a stripclub. Both are looking at the women to their left, including Jane, one of the eponymous 'bonnes femmes', at the right edge of the frame. Closest to the camera, left of frame, is Jacqueline, admiring the leopard-skin pillion of a Harley-Davidson. The two women have come onto the street in a group of nine friends from an arcade. Furthest from the camera, one of the group is running to fetch a taxi; in front of him, centre frame, is the motorcyclist who stalks Jacqueline through the film.

Of equal interest, at least to me, are the non-human things aligned along this street: buildings, vehicles, signs.

This, below, is a cinema, the Biarritz, a substantial part of a late '20s block occupying the corner with the Champs Elysees:

This, below, is a cinema, the Biarritz, a substantial part of a late '20s block occupying the corner with the Champs Elysees:

Sight of a cinema in a New Wave film immediately suggests reflexivity. We remember the Astor in Les 400 coups (1959), or the Cineac Italiens:

Or the Mac-Mahon and the Napoléon in A bout de souffle (1960):

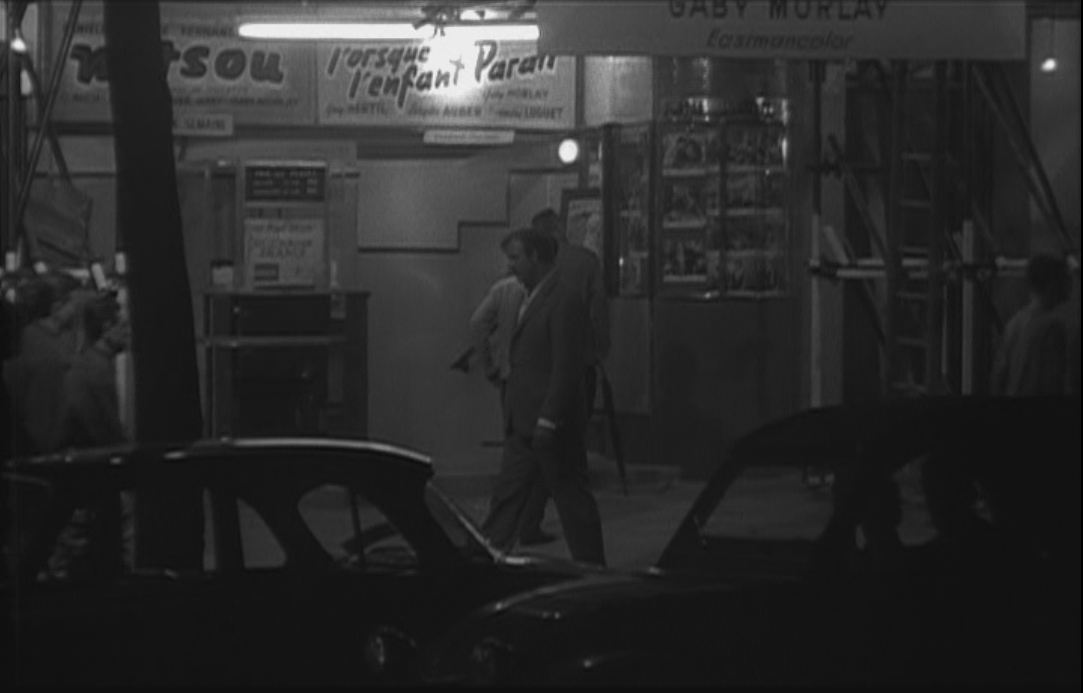

When we can see what film is playing at that cinema, reflexivity is multiplied by intertextuality - the films playing above are John Ford's The Long Gray Line ['Ce n'est qu'un au revoir'] (1955) and Budd Boetticher's Westbound (1959). See also the double bill of Jacqueline Audry's Mitsou (1956) and Michel Boisrond's Lorsque l'enfant paraît (1956), playing at the Boul'Mich in Rohmer's Le Signe du lion (1959), or Henry Hathaway's La Cité disparue [Legend of the Lost] (1957) at the Gaumont Richelieu in Rivette's Paris nous appartient (1960):

|

The richness of the intertext will vary according to the film referenced. Richest of the examples above is Hathaway's Legends of the Lost, especially in its French title, 'the lost city', which then comes to describe the Paris of Rivette's film. On the other hand I can make nothing of the double bill of sex comedies in Le Signe du lion (that may change when I get around to watching those films, but I doubt it).

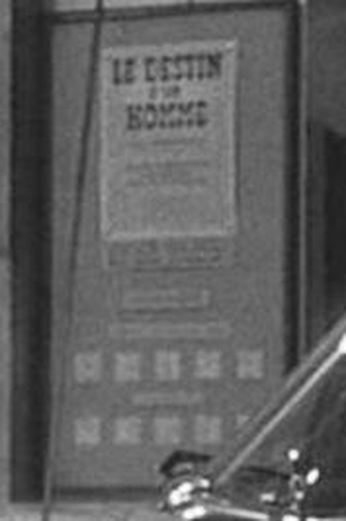

In Les Bonnes Femmes we can see that the film playing at the cinema next to the Grisbi-Club is Sergei Bondarchuk's Le Destin d'un homme [Sudba cheloveka] (1959), but it is hard to see a connection between the two films. It would be different if the Soviet film were playing in Le Signe du lion, focused as Rohmer's film is on 'the destiny of a man'. |

In the following sequence of Les Bonnes Femmes Jane and Jacqueline discuss matters in front of the Raimu cinema, at 63 avenue des Champs Elysées, where The Buccaneer (1958) is playing. Again, I cannot see that the referenced film brings anything to the referencing film. At a stretch it might have worked in A bout de souffle, as the last film of a great director, Cecil B. DeMille, framed by an unknown's first. Even then it wouldn't have matched what actually was playing in A bout de souffle at another Champs Elysées cinema, the George V - Resnais's Hiroshima mon amour (1959) supported by Varda's 1958 short Du côté de la côte:

The intertextualities of Chabrol's Les Bonnes Femmes are of a different order, as we may see in returning to its opening sequence in the rue Quentin Bauchart.

Parked outside the Biarritz cinema is a 1954 Cadillac, Series 62, the same car exactly (matriculation: 77 54 CR 75) that had been stolen two months earlier by Belmondo and Seberg in A bout de souffle:

Vehicular intertextuality is not the object of this post, but we can observe in passing that it is more likely to bear upon A bout de souffle than upon Les Bonnes Femmes. The Internet Movie Cars Database lists 48 vehicles for Les Bonnes Femmes, but only two of any significance (the Cadillac and the Harley-Davidson), whereas for A bout de souffle 121 vehicles are listed, with eleven marked as significant. To this quantitative reading we could add a qualitative assessment of the role cars play and the significance they bear. The presence of a particular car can be like the appearance of a particular person in a cameo role. In A bout de souffle there is a Ford Thunderbird belonging to the director-producer José Benazeraf, who appears in the film as the man from whom it is stolen. Actor Roger Hanin appears later in a cameo, but not before the 1952 Jaguar XK 120 Roadster (matriculation: 71 26 EG 75) he had been driving in Une balle dans le canon (1958) makes its own appearance, driving up the Champs Elysées:

Though I'd like to be working out how this car came from one film to the other (was it Hanin's own car?), I need to get back to the rue Quentin Bauchart.

Directly across the street from the Biarritz is a Citroen DS, parked in front of a late nineteenth-century apartment building, with the Bella Napoli restaurant on the ground floor. There is still an Italian restaurant at this address, 25 rue Quentin Bauchart:

Directly across the street from the Biarritz is a Citroen DS, parked in front of a late nineteenth-century apartment building, with the Bella Napoli restaurant on the ground floor. There is still an Italian restaurant at this address, 25 rue Quentin Bauchart:

(The vomiting man, above, is one of the incidents cut from the U.S. print of Les Bonnes Femmes.)

Next along, on the corner with the Champs Elysées, was (as is now) a branch of the Société générale bank, better seen in a shot, below right, from the following sequence. The neon signage on this building advertises forthcoming film releases by the Sofradis distribution company, mentioning the Rex and Normandie cinemas and what looks like Brèves Amours (1959), a film with Vittorio de Sica and Michèle Morgan:

Next along, on the corner with the Champs Elysées, was (as is now) a branch of the Société générale bank, better seen in a shot, below right, from the following sequence. The neon signage on this building advertises forthcoming film releases by the Sofradis distribution company, mentioning the Rex and Normandie cinemas and what looks like Brèves Amours (1959), a film with Vittorio de Sica and Michèle Morgan:

Back in the rue Quentin Bauchart, on the other side of the street, there is an exit from the arcade that runs through the building and out onto the Champs Elysées. We can see the other exit seven years later in Bunuel's Belle de jour (1967), as well as a different view of inside the arcade:

(The stills by the entrance in Belle de jour are from Lelouch's 1966 film Un homme et une femme.)

It is not a coincidence that the same building serves in Les Bonnes Femmes and Belle de jour, since the building also housed the offices of Paris-Film Production, the company run by Robert and Raymond Hakim, and both films were produced by the Hakim brothers: this is a local location.

It is not a coincidence that the same building serves in Les Bonnes Femmes and Belle de jour, since the building also housed the offices of Paris-Film Production, the company run by Robert and Raymond Hakim, and both films were produced by the Hakim brothers: this is a local location.

Next to the arcade exit is the entrance to the Grisbi, a stripclub to which we shall return at length, later. After this is an entrance to a dancehall, the Mimi Pinson. This club specialised in Latin-American music, as can be heard on the soundtrack throughout this sequence. It had a reputation as a place to pick up women, as the 1963 Fodor Guide to Europe makes clear: 'Soft lighting, continuous dancing, with two bands, starting early in the afternoon. This is another spot where you should be able to find a partner.' (The 1967 edition of Fodor is even more explicit: 'Soft lights and sweet music and quite often a perfect stranger in your arms. You can ask any girl to dance with you. This is what she came for.')

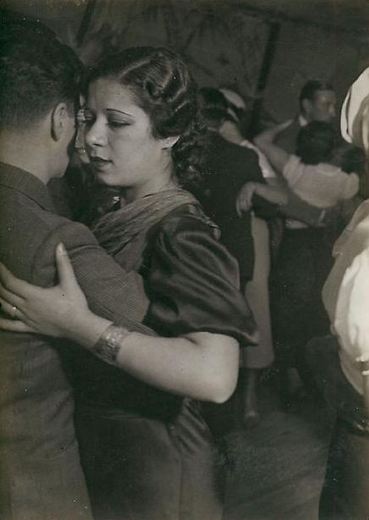

As the signs on these doors indicate, the principal entrance was in the arcade, the galerie. The friends have been dancing, though we don't see where they have been dancing until the end of the film, in its famous coda. The closing sequence of Les Bonnes Femmes has been read as discontinuous and disconnected, which it is in terms of narrative temporality, but topography connects it strongly to the film's opening sequence, since this is the inside of the Mimi Pinson dancehall:

The band playing is that of Denis Tuveri, the accordeon and bandoneon specialist who also, as here, played the trumpet. Also featured is his wife, the singer and violinist Lina Bossatti:

|

It is the Latin American dance music being played by Tuveri's band that connects directly to the beginning of the film, where we hear, overlapping, both a tango and (I think) a javanaise.

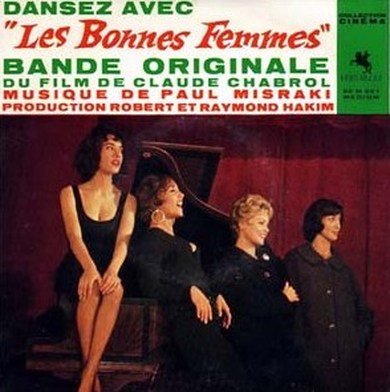

The E.P. of the score of Les Bonnes Femmes reproduced none of the discordant music accompanying the dramatic moments of the film (composed by Pierre Jansen - see here), but only a set of Latin American dance numbers composed by Paul Misraki and associated with each of the women: |

'Samba pour Jeanne', 'Rita Mambo', 'Rock pour Ginette' and 'Tango pour Jacqueline', as well as the 'Valse des bonnes femmes' with which the film comes to a close. There is also 'La Java d'Ernest', for the stalker Ernest Lapierre (who seems to have become André Lapierre on IMDB, though he introduces himself as Ernest in the film).

To know just from the topography that the film has returned to its opening would require an ability to recognise the dance floor of the Mimi Pinson. It was a famous establishment, dating back to 1937, but I doubt that many in the first audiences made the connection. In the opening sequence we do see, by the entrance, photographs showing Tuveri's band, but they are too small and go past too quickly to be remembered ninety minutes later when we see the band in action:

To know just from the topography that the film has returned to its opening would require an ability to recognise the dance floor of the Mimi Pinson. It was a famous establishment, dating back to 1937, but I doubt that many in the first audiences made the connection. In the opening sequence we do see, by the entrance, photographs showing Tuveri's band, but they are too small and go past too quickly to be remembered ninety minutes later when we see the band in action:

Next along from the dancehall is the showroom of an electrical goods shop, Ecofroid. Jane make an explicit connection with a place we shall see later when she points to a model of oven that they don't have where they work, an electrical goods shop on the other side of Paris, near the Bastille.

This connection with a space to come is the inverse of the return to the dancehall, in that we are not given the means to recognise the dancehall at the end as the one at which the women had been at the beginning (since we don't see them in there), whereas the two shops are so similar in how they are shown that someone might well confuse the two (see here), and think that the women's place of work is next door to a stripclub.

At the end of the street, at the corner with the Champs Elysées, is a hoarding covered with posters. The big one, below left, is for a tinned 'potage provençal', brand Liebig - the slogan reads '... les pieds sous la table'. The smaller ones are notices of theatrical productions - a reprise of François Campaux's play Chérie noire at the Bouffes Parisiens, and Roland Petit's Ballets de Paris production of Cyrano de Bergerac, with music by Marius Constant, at the Théâtre de l'Alhambra:

At the end of the street, at the corner with the Champs Elysées, is a hoarding covered with posters. The big one, below left, is for a tinned 'potage provençal', brand Liebig - the slogan reads '... les pieds sous la table'. The smaller ones are notices of theatrical productions - a reprise of François Campaux's play Chérie noire at the Bouffes Parisiens, and Roland Petit's Ballets de Paris production of Cyrano de Bergerac, with music by Marius Constant, at the Théâtre de l'Alhambra:

As promised, we return to the Grisbi-Club.

2/ striptease and neon

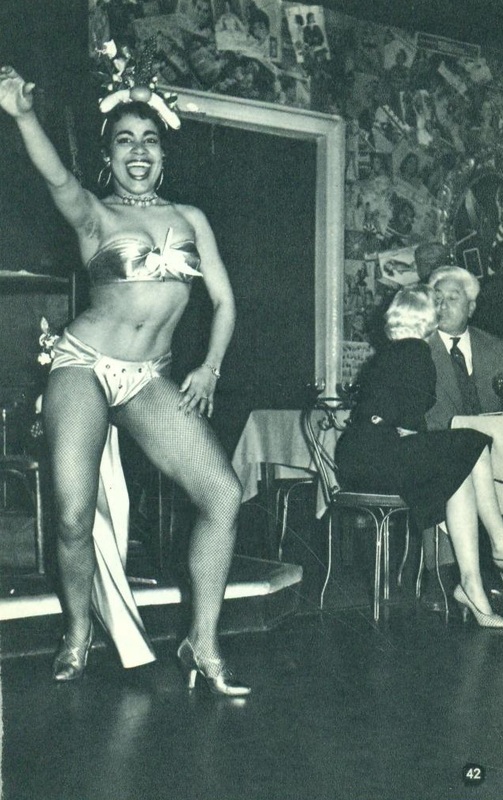

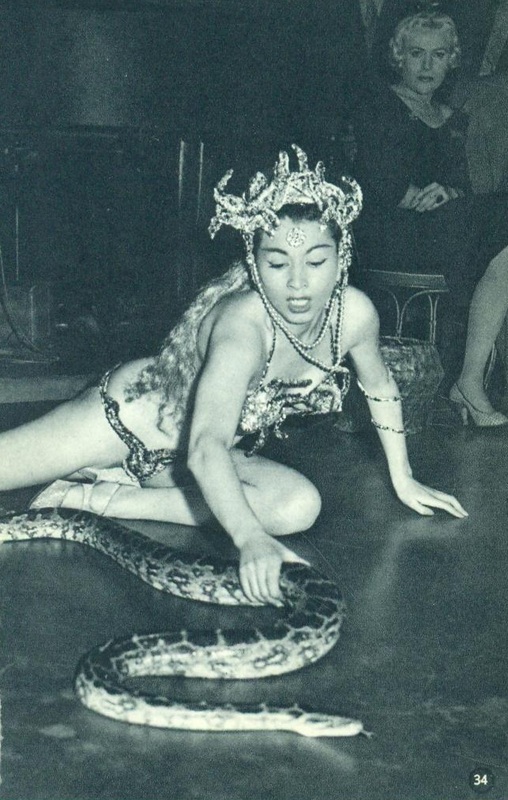

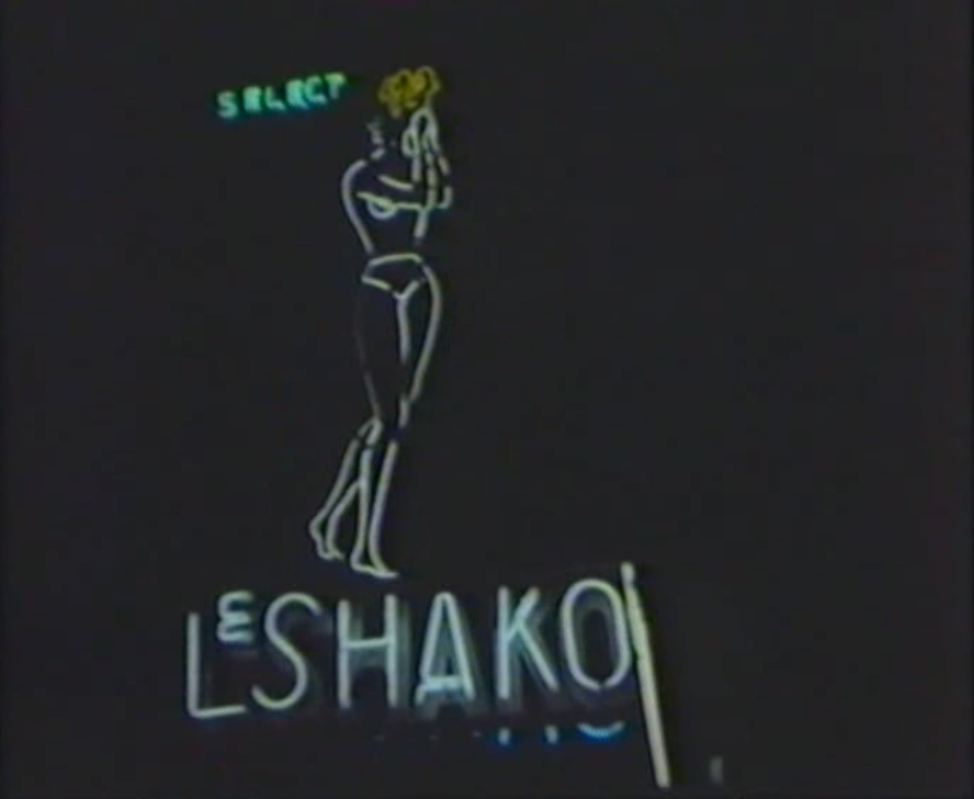

The Grisbi was a striptease and 'variétés' club, one of dozens that thrived in Paris after the Crazy Horse Saloon established the vogue for striptease in the early 1950s. It advertised itself as 'le cabaret en vogue' of the Champs-Elysées. Jacques Robert, in his Paris By Night: a Tour of the Capital's Gay Pleasure Haunts (1956), comments: 'The Grisbi is papered very effectively with magazine pictures, and has good cabaret turns.' Lawrence and Sylvia Pass Martin, in their Paris and its Environs: an Uncommon Guide (1963), were less than impressed: 'The Champs area offers, besides the Crazy Horse: Le Sexy (68 rue Pierre Charron), Le Grisbi (22 rue Quentin Bauchart) and Le Shako (corner of George V and rue Vernet). Sexy and Grisbi have little more to their show than stripping.'

For an impression of the kind of act on show at the Grisbi, see these three photographs taken there by Daniel Frasnay for Jan Brusse's 1957 book Paris Oh La La:

For an impression of the kind of act on show at the Grisbi, see these three photographs taken there by Daniel Frasnay for Jan Brusse's 1957 book Paris Oh La La:

This role is familiar from 1950s French films with a cabaret or stripclub setting, sometimes, as in Les Bonnes Femmes, filled out with dialogue and gesture, other times just as a background figure. Below are some examples:

La Tournée des grands ducs (1953) has the protagonist stand in as the club doorman, the most substantial doorman-related business I have come across in these films, except for the character role played by Carette in La Môme Pigalle (1955):

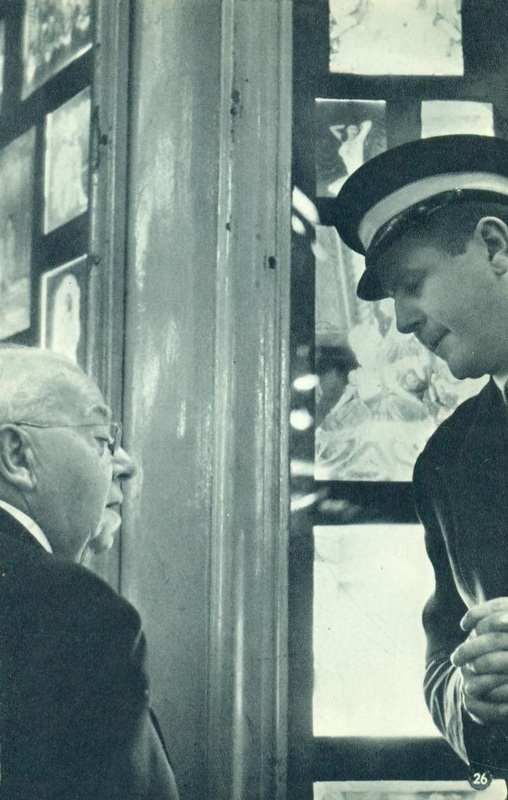

Remarkably, and no doubt coincidentally, one of the potential customers importuned by the doorman in La Môme Pigalle is the same man who is importuned on emerging from the Grisbi-Club in Les Bonnes Femmes - Chabrol's doorman asks him if he is planning to go home alone, and gets a scathing look as reply:

(I haven't found the name of this characterful extra who seemed to specialise in expressing indignation, but he does turn up at an art-gallery opening in Chabrol's next film, Les Godelureaux, and he is a member of the jury in Landru, from 1963.)

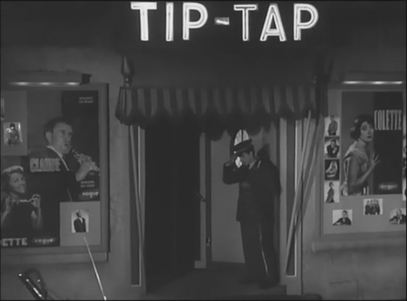

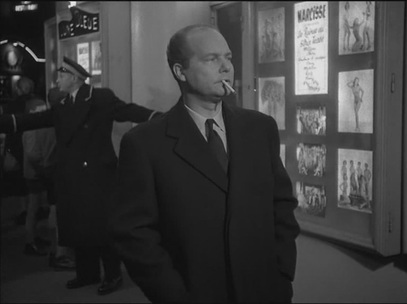

One of Chabrol's departures from '50s norms is to have used a real club's real name. In the examples above the first four - Le Ruban Bleu, Le Toboggan, Le Tip-Tap and Le Pégase - are studio sets with invented names passing for real clubs on real streets. The next two give invented names to real clubs - L'Age d'or = Le Piccadilly, La Main chaude = Le Sphinx - and the last three leave the real name in place (Le Narcisse) or just leave the identification of the club to the cognoscenti. The naked woman riding a horse and pulling a wagon, below, is the famous façade of La Roulotte, a club long associated with Django Reinhardt. The man being moved along by the doorman is played by Sacha Briquet, Henri in Les Bonnes Femmes:

|

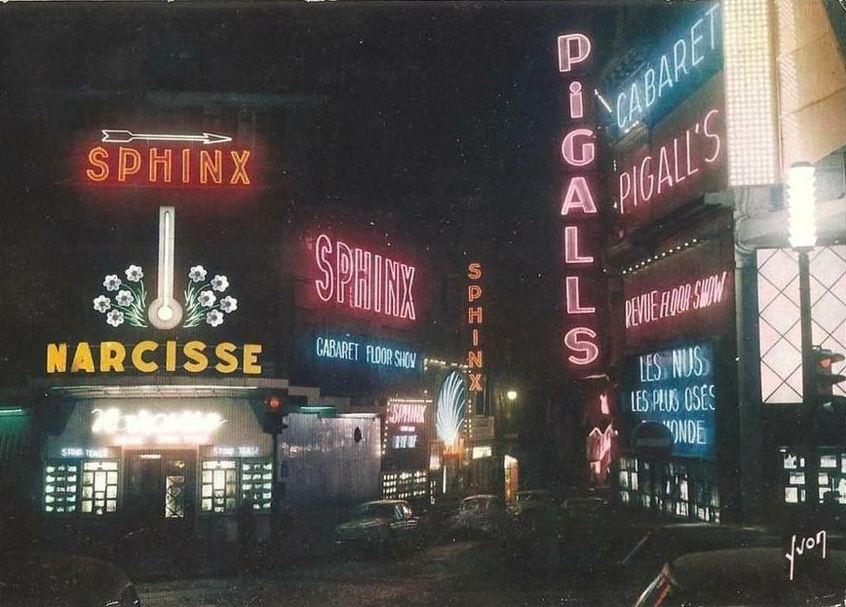

All of these clubs pretend to be or are actually in Pigalle, an area with a great concentration of such establishments and which, by their distinctive signage, is easy to establish as a locale.

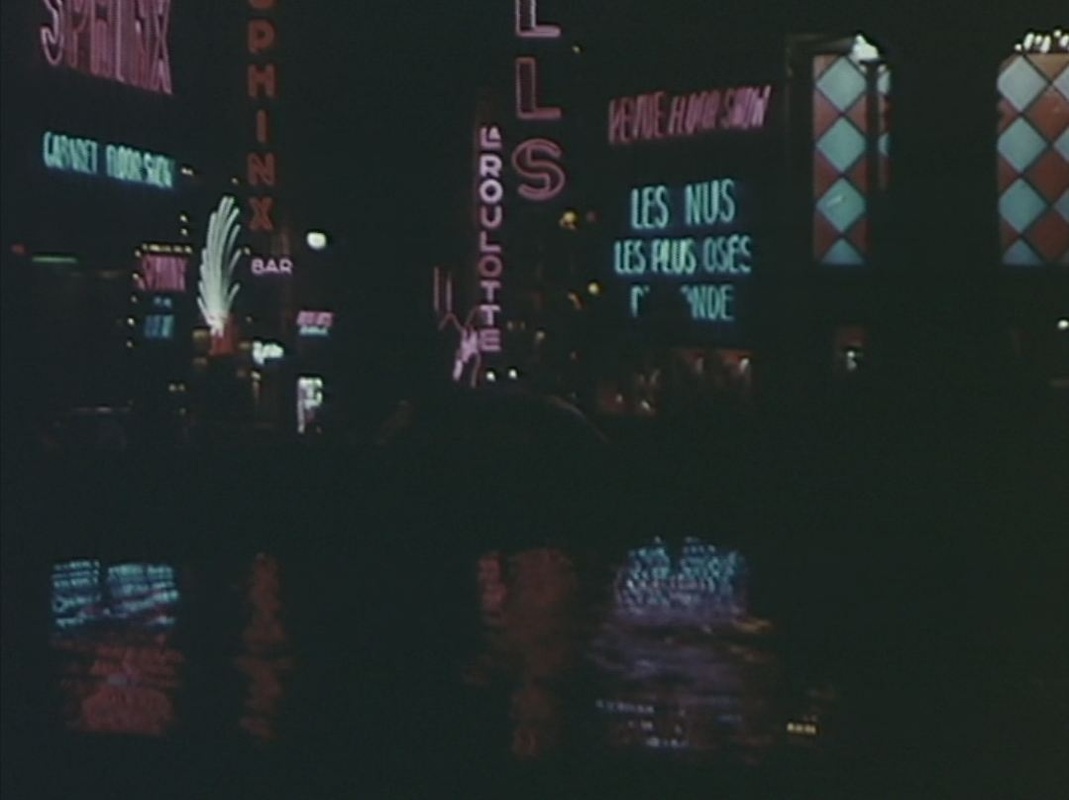

The images right are from the Pigalle-set parts of a dozen or so films made between 1949 and 1961: |

|

|

|

The fullest use of this localising signage that I have come across is at the climax of sex-change comedy Adam est... Eve (1954), where the man who has become a woman is due to appear nude in a Pigalle nightclub. Eight different illuminated signs for real clubs are dsplayed, left, before a sandwich man's board gives the name of the 'Adam et Eve', the invented place where she will perform.

|

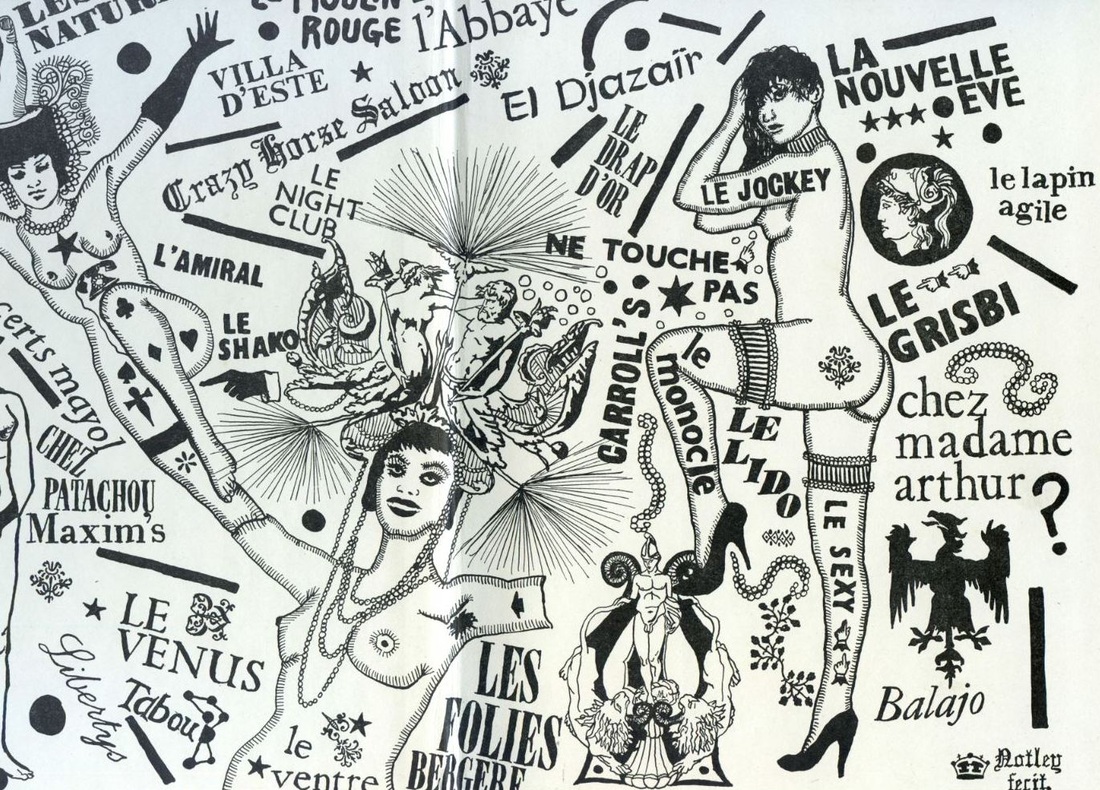

Another departure in Les Bonnes Femmes is to have kept out of Pigalle entirely, preferring the vicinity of the Champs Elysées, a more elegant neighbourhood, even if there was a comparable concentration of such establishments:

At the end of its opening sequence Les Bonnes Femmes gives us a brief glimpse of the Lido across the Champs Elysées:

To the Grisbi and the Lido, Les Bonnes Femmes adds a third stripclub, the one to which the two dragueurs take Jane and Jacqueline later that evening:

We only see the interior of this third club. The stripper performing here is the memorable Dolly Bell, star of the Crazy Horse Saloon, and though her act is very much like the act she was known for there, from the décor and the layout of the tables and stage we can see that this is not the Crazy Horse:

Dolly Bell does her act again, in yet another venue, in Jean-Daniel Pollet's Gala (1961):

And she worked on another New Wave film the following year, Doniol-Valcroze's La Dénonciation, serving as advisor to Françoise Brion for the amateur strip she stages for her husband after they have seen a show at a club very like the Crazy Horse:

Acts from the Crazy Horse did feature in several films around this time, including Jacques Poitrenaud's Strip-tease (1963) and José Benazeraf's 24 heures d'un Américain à Paris (1963):

The place where Chabrol restages Dolly Bell's act is in fact La Villa, a small stripclub on the rue Bréa in Montparnasse, seen here as photographed by Daniel Frasnay in the 1950s:

The plate-smashing in Chabrol's film would make La Villa immediately recognisable to spectators familiar with the Paris nightclub scene. Here is a description from Paris By Night (p.72): 'At the Villa the problem of attraction is permanently solved, for the "attraction" is the public itself! At this establishment you can break plates on your neighbour's head, and all at the expense of the management.' Fielding's Travel Guide to Europe (1966 edition) is more specific: 'La Villa (27 rue Brea) offers a grubby adult-playpen atmosphere, noise, strippers, $4 whisky, the breaking of stage crockery, 3 barmaids, and a performer-customer conga line to brave souls who take triple doses of vitamin pills.'

Below are details from a 1960 Pathé newsreel about La Villa's plate-smashing phenomenon (you can see the clip here):

Below are details from a 1960 Pathé newsreel about La Villa's plate-smashing phenomenon (you can see the clip here):

The area of Montparnasse around La Villa was an enclave of clubs, including La Boule Blanche and L'Eléphant Blanc on the rue Vavin, La Canne à Sucre on the rue Sainte-Beuve and, on the boulevard du Montparnasse, Le Jockey and Le Vénus. Had Chabrol filmed in the streets around La Villa we might well have seen the party atmosphere spill out in the manner of the Pathé film, where the plate-smashing carries on outside, with customers running hysterically down the street. The exterior of the Grisbi Club with which Les Bonnes Femmes opens represents a more sobre milieu, lacking the gaiety of Montparnasse, or the confusion and excess of the usual Pigalle setting for a stripclub entrance.

The doorman supplements the sobriety of these environs with his monotone mantra, 'les plus beaux nus de Paris' (the most beautiful nudes in Paris), a low key alternative to the slogan that dominated the place Pigalle: ' Les nus les plus osés du monde' (the most daring nudes in the world):

The evocative illuminations of Pigalle make the signage on the rue Quentin Bauchart seem perfunctory - Rika Zarai is an Israeli singer and Bel Air is her record label; Bendix is a brand of electrical appliance. Occasionally a neon of a recumbent nude lights up under the Grisbi sign, but it is a modest thing compared with the riches of Pigalle.

3/ the New Wave in Pigalle

Some members of the group in Les Bonnes Femmes decide to follow their soirée of dancing with a trip to Pigalle, but the film doesn't follow them there. One of them suggests Le Perroquet vert (rue Cavallotti, 18e), a restaurant popular with film actors (e.g. Jean Gabin), but we follow instead the two women who go their own way, walking past the Grisbi-Club onto the Champs Elysées.

Had Chabrol preferred Pigalle over the Champs Elysées for his opening sequence, its first shot might have looked more like the image left, below, than like the image right:

Had Chabrol preferred Pigalle over the Champs Elysées for his opening sequence, its first shot might have looked more like the image left, below, than like the image right:

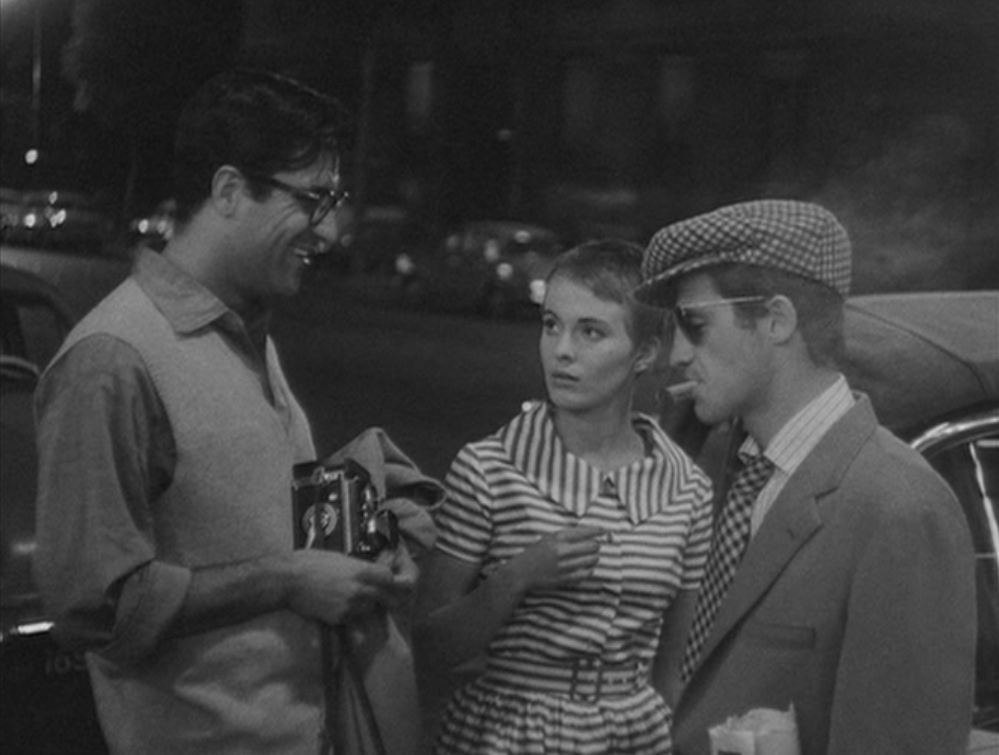

Both of the above are the work of cinematographer Henri Decae, moving with ease from the proto-New Wave of Bob le flambeur to the New Wave proper. Before shooting Les Bonnes Femmes Decae had already photographed Pigalle for a New Wave film. In Les 400 coups, when Antoine is being carted off to borstal, we watch with him as he sees the last of Paris through the bars of the van:

There is an irony in this clichéed vision of the city Antoine is forced to leave, because though he has hitherto been shown in and around the 9e arrondissement, he is never shown in proximity to the bars and nightclubs of Pigalle. At one point his friend René arranges to meet him by the fountain in the place Pigalle, but we do not see the encounter. Later, we see two cafés on the place Blanche, briefly, but not the place Blanche's most famous feature, the Moulin Rouge:

Truffaut was brought up in the area, but the hub for him was not the gaudy, neon-lit place Blanche or place Pigalle but the place Clichy, further west, at the edge of what is called Pigalle. Truffaut shows us the place Clichy several times, and also the boulevard de Clichy up to the rue Caulaincourt and the Gaumont Palace:

Les 400 coups concentrates on less sensational sides of the 9e, such as Antoine's home by the place Gustave Toudouze or René's home in the avenue Frochot:

(See here for a detailed identification of Paris locations in Les 400 coups).

The following year, old-school director Julien Duvivier would take Truffaut's actor Jean-Pierre Léaud for his film Boulevard and cast him in a role very much like that of Antoine Doinel, except that he has him live in a garret on the place Pigalle, embedding him in the clichéed milieu that Truffaut had carefully avoided:

|

The New Wave in general tended to avoid Pigalle. Towards the end of A bout de souffle, two petty criminals meet up outside La Coupole on the boulevard du Montparnasse. One of them is on the run from the police, and asks the other where he and his girlfriend can spend the night. The girlfriend suggests that they could stay with a friend of hers in Montmartre, and gets a sharp answer: |

‘No, not Montmartre… We’ve got too many enemies in Montmartre.’

By Montmartre is meant here, precisely, the seedy environs of the place Pigalle, the criminal milieu of old-school French gangster films.

In Paris nous appartient, two characters walk across Paris from Montmartre to the 6e arrondissement. We are shown several stages on their journey, but nothing between the place Emile Goudeau, 18e, and the boulevard Poissoniere, 2e, to get to which they would almost certainly have passed through Pigalle.

In Le Signe du lion, a group of friends go drinking in Pigalle, and we get glimpses of the place Pigalle and the place Blanche. This is just a thirty-second sequence in a film otherwise resolutely centred in the 5e and 6e arrondissements:

By Montmartre is meant here, precisely, the seedy environs of the place Pigalle, the criminal milieu of old-school French gangster films.

In Paris nous appartient, two characters walk across Paris from Montmartre to the 6e arrondissement. We are shown several stages on their journey, but nothing between the place Emile Goudeau, 18e, and the boulevard Poissoniere, 2e, to get to which they would almost certainly have passed through Pigalle.

In Le Signe du lion, a group of friends go drinking in Pigalle, and we get glimpses of the place Pigalle and the place Blanche. This is just a thirty-second sequence in a film otherwise resolutely centred in the 5e and 6e arrondissements:

We should discount Louis Malle's Zazie dans le métro (1960) as at best a para-New Wave film, but it does have splendid views of the place Blanche and the place Pigalle, revelling in the spectacle of neon:

Jean Eustache's first film Les Mauvaises Fréquentations (1963), aka Du côté de Robinson, is an authentic New Wave study of Montmartre and Pigalle through the behaviour of two very unpleasant dragueurs. Here they are on the boulevard de Clichy and the place Blanche (the Robinson is a dancehall next to the Moulin Rouge):

Eustache shows the area in the grey light of day, drab and unspectacular, but there is one authentic New Wave film that spends time in Pigalle and, like Zazie dans le métro, makes cinematic spectacle out of neon signage. Guy Gilles's L'Amour à la mer (1963) is a beautiful film, unjustly ignored:

The protagonist even meets Jean-Pierre Léaud in the place Clichy, as if Léaud hasn't moved from there since Les 400 coups and Boulevard (he's actually begging for money so that, he claims, he can get home to the suburbs):

Truffaut himself will bring Léaud back to the area in sequels to Les 400 coups:

Through Truffaut, the area around the place Clichy and the Gaumont Palace is a part of Pigalle that the New Wave can lay claim to. Like Guy Gilles in L'Amour à la mer, Jean Eustache in Les Mauvaises Fréquentations goes there in homage to Truffaut's Paris:

The same can be said of Godard. He is close to Truffaut territory when in Les Carabiniers (1963) he films Le Mexico cinema at 110 boulevard de Clichy:

Likewise when in 'Il nuovo mondo' (1963) he films the lights of the place Blanche (below left). But when he films in the place Clichy (below right), looking up towards the Gaumont Palace, he is quoting Truffaut:

He is quoting Truffaut again when, as the narrator in Bande à part (1964), he calls the place Clichy one of the most beautiful in Paris, with its 'lumière de charbon':

Some time around 1960, the owner of a boutique at 130 boulevard de Clichy decided to give a modern air to her business by calling it Nouvelle Vague. Both Eustache and Godard filmed the shop's neon sign as a sign of the New Wave's attachment to this particular part of the city:

The shop, incidentally, is still there, though it has modified its signage:

4/ a Grisbi connection: Les Nymphettes

Henri Zaphiratos's Les Nymphettes (1961) is a justly ignored film about the sexual mores of young women and the frustration they engender in young men. A broad definition would allow this as a New Wave film, if a bad one. It belongs among a number of films - both old school and New Wave - from the late '50s onwards that presented themselves as studies of particular social groups or categories, beginning with Les Tricheurs (Marcel Carné 1958) and including Les Dragueurs (Jean-Pierre Mocky 1959), Les Bonnes Femmes (Claude Chabrol 1960), Les Godelureaux (Claude Chabrol 1961), Les Parisiennes (Michel Boisrond et al., 1962), Les Vierges (Jean-Pierre Mocky 1963) and La Fleur de l'âge, ou Les Adolescentes (Jean Rouch et al., 1964).

Zaphiratos's observations of youth are modelled on those of Chabrol in Les Cousins (1958), and his film shares a number of minor cast members with Chabrol's, but chief among Les Nymphettes' New Wave credentials, such as they are, is the use of real locations, both interiors and exteriors. Outside a fashionable Montparnasse nightspot, L'Epi Club, the male protagonist is rejected by a girlfriend in favour of a man with an Alfa Romeo. He begins a slow mournful trek across Paris by night, past cafés and cabarets, amorous couples and importunate prostitutes. He goes into a cinema (to see Danny Kaye as Red Nichols in The Five Pennies - I can't think why) and, after crossing the river by the pont de la Concorde, ends up near the Champs Elysees.

The nightclubs on his itinerary interest me most, especially the last two of them:

Zaphiratos's observations of youth are modelled on those of Chabrol in Les Cousins (1958), and his film shares a number of minor cast members with Chabrol's, but chief among Les Nymphettes' New Wave credentials, such as they are, is the use of real locations, both interiors and exteriors. Outside a fashionable Montparnasse nightspot, L'Epi Club, the male protagonist is rejected by a girlfriend in favour of a man with an Alfa Romeo. He begins a slow mournful trek across Paris by night, past cafés and cabarets, amorous couples and importunate prostitutes. He goes into a cinema (to see Danny Kaye as Red Nichols in The Five Pennies - I can't think why) and, after crossing the river by the pont de la Concorde, ends up near the Champs Elysees.

The nightclubs on his itinerary interest me most, especially the last two of them:

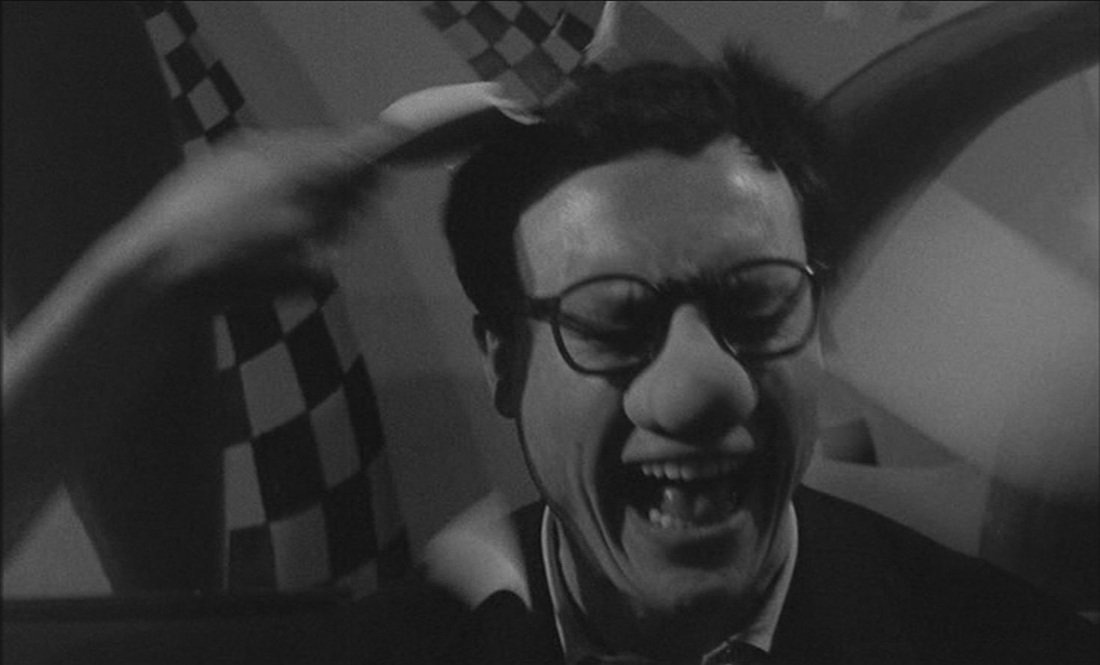

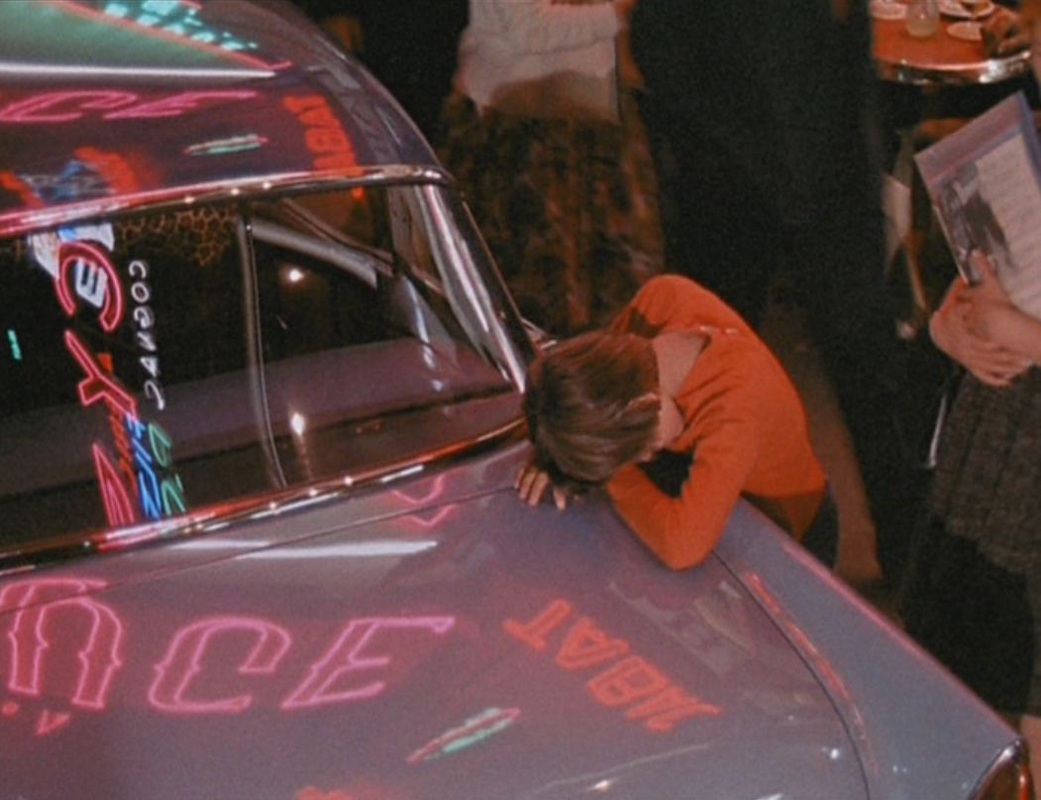

He is walking past the Grisbi-Club as a young woman is pulling across the grill to close up. She sells cigarettes in the club, and invites him in to see what the club looks like when its empty:

The young woman is played by Colette Descombes, who will acquire her own New Wave credentials as the taller of the two Brigittes in Luc Moullet's Brigitte et Brigitte (1966). She demonstrates for the young man what would be her idea of a striptease act:

After its introduction to France in the early 1950s, striptease was frequently represented in old school French films, especially those set in Pigalle. Les Nymphettes is one of a small number of New Wave films that show interest in striptease. The others include Chabrol's Les Bonnes Femmes (of course), Une femme est une femme (Jean-Luc Godard 1961), Gala (Jean-Daniel Pollet 1961), L'Oeil du malin (Claude Chabrol 1962), La Dénonciation (Jacques Doniol-Valcroze 1962) and Une femme mariée (Jean-Luc Godard 1964). A thorough study of New Wave striptease would have to look at the strips performed in José Benazeraf's New Wavish erotica (Le Concerto de la peur, La Nuit la plus longue, L'Enfer sur la plage and Joe Caligula), as well as those in Claude Lelouch's documentary La Femme spectacle. That study is something I am undertaking elsewhere. For the time being I shall return to the Grisbi connection.

|

Les Nymphettes was shot in the months following the release of Les Bonnes Femmes in April 1960. The similarity of title, the presence of Chabrol-associated actors, the views of La Villa and the Grisbi-Club, and the performance of a strip are all indications of a marked influence of the one film on the other.

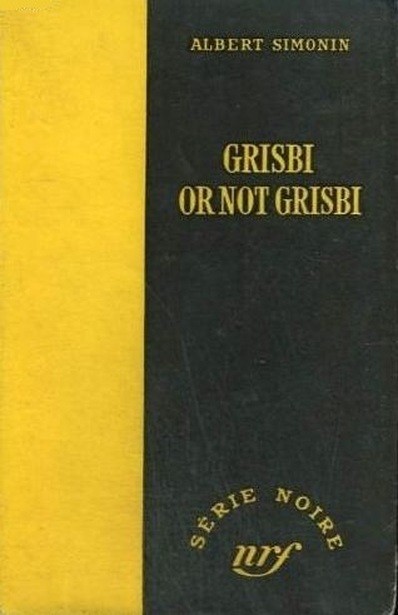

By contrast, similar indications of a connection between Les Bonnes Femmes and Becker's Touchez pas au grisbi are harder to find. I had thought that Chabrol's use of the Grisbi-Club might be signposting an intertextuality to be unpacked, like the bar called Casablanca in Hiroshima mon amour, or the cabaret called L'Eldorado in Jacques Demy's Lola - both real places implicating the fictions of other films. |

There are already several rich readings of the Casablanca connection in Resnais's film, and much could be made from a comparison of Demy's Lola and L'Herbier's Sibilla (in El Dorado, 1921), both cabaret-dancing single mothers.

I can't see much that is fruitful in the Becker/Chabrol Grisbi connection, even if I come back to my interest in striptease. It is a coincidence, finally, that both films feature women performing in a state of undress. Unlike the contrast of private and public striptease in Les Nymphettes and Les Bonnes Femmes, connected by reference to the same locale, the kinds of nudity here, below, are harder to connect:

I can't see much that is fruitful in the Becker/Chabrol Grisbi connection, even if I come back to my interest in striptease. It is a coincidence, finally, that both films feature women performing in a state of undress. Unlike the contrast of private and public striptease in Les Nymphettes and Les Bonnes Femmes, connected by reference to the same locale, the kinds of nudity here, below, are harder to connect:

La Villa in Les Bonnes Femmes conforms to a basic and modern formula, whereas Le Mystific in Touchez pas au grisbi is not a stripclub at all but a high-end nightclub with a floorshow featuring semi-naked dancers in elaborate and slightly ridiculous routines. I could just about argue that in Les Bonnes Femmes the name of the Grisbi-Club evokes a memory of the old-fashioned routine on show in Becker's film, but I'd rather say that Dolly Bell's act and the behavious of the audience are figures of New Wave modernity, effacing our memory of Becker's old world cabaret.

Performed nakedness is the best intertext I could find in which to read these two films together. I did think about the reprise by Chabrol of one cast member from Touchez pas au grisbi, but the screentime allotted bit-player Charles Bayard in both films is too brief to establish an intertext of any substance, and is also just a coincidence:

Performed nakedness is the best intertext I could find in which to read these two films together. I did think about the reprise by Chabrol of one cast member from Touchez pas au grisbi, but the screentime allotted bit-player Charles Bayard in both films is too brief to establish an intertext of any substance, and is also just a coincidence:

So I shall leave the Becker/Chabrol connection aside now, and concentrate in conclusion on a street in Montparnasse, as seen in Touchez pas au grisbi.

5/ 33 rue Blomet, 15e

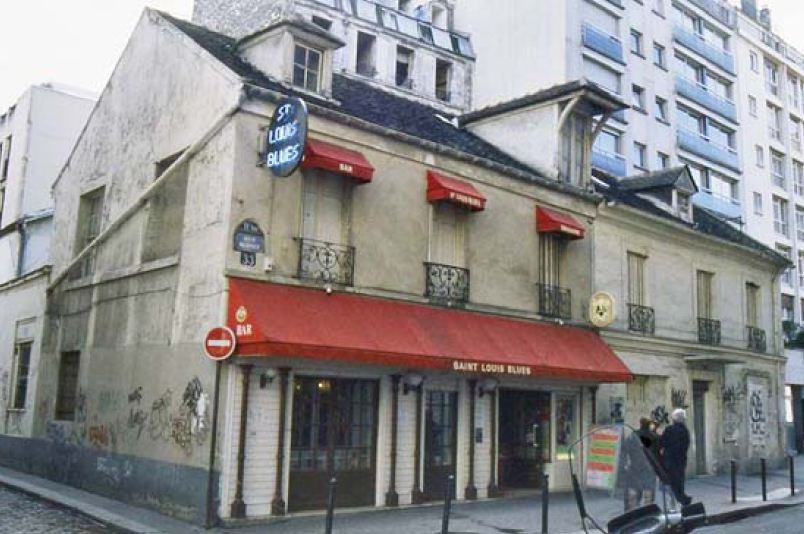

The rue Quentin Bauchart in Les Bonnes Femmes was easy to find, once a phone directory gave me the address for the Grisbi-Club and Google Maps showed me what the street looks like now:

But it took me a lot longer to find this street:

|

I'd assumed this was in the Pigalle area, because the film's opening cuts from a view of the Moulin Rouge on the place Blanche to a restaurant interior from which, eventually, characters emerge onto this street.

I looked in a 1950s directory for all of the hairdressing salons in Pigalle and Motmartre, and then for all of the restaurants (those are the two businesses each side of that arched entrance), but with no luck. |

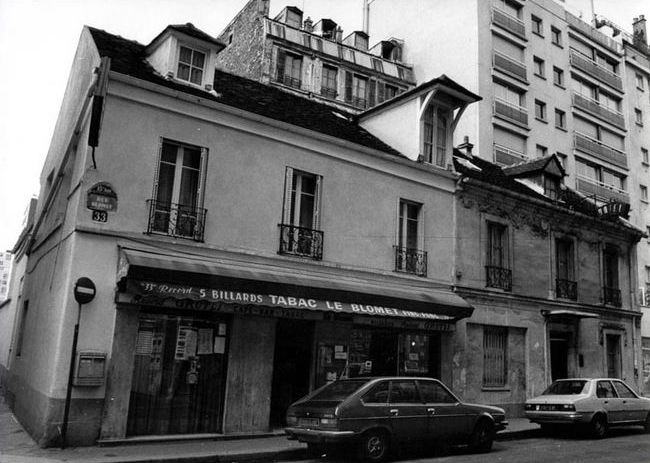

Then I saw that just behind is a sign for a veterinary clinic, so looked up all of those in Paris, and found the street, in the 15e arrondissement, kilometres from Pigalle. The vet is no longer there, but the restaurant is still a restaurant and the hairdresser's still a hairdresser's. This building is no. 42 rue Blomet:

The shot above is the last exterior view in Becker's film, and the only time we see the street in daylight. Most of the other views are of the other side of the street, and all are at night time:

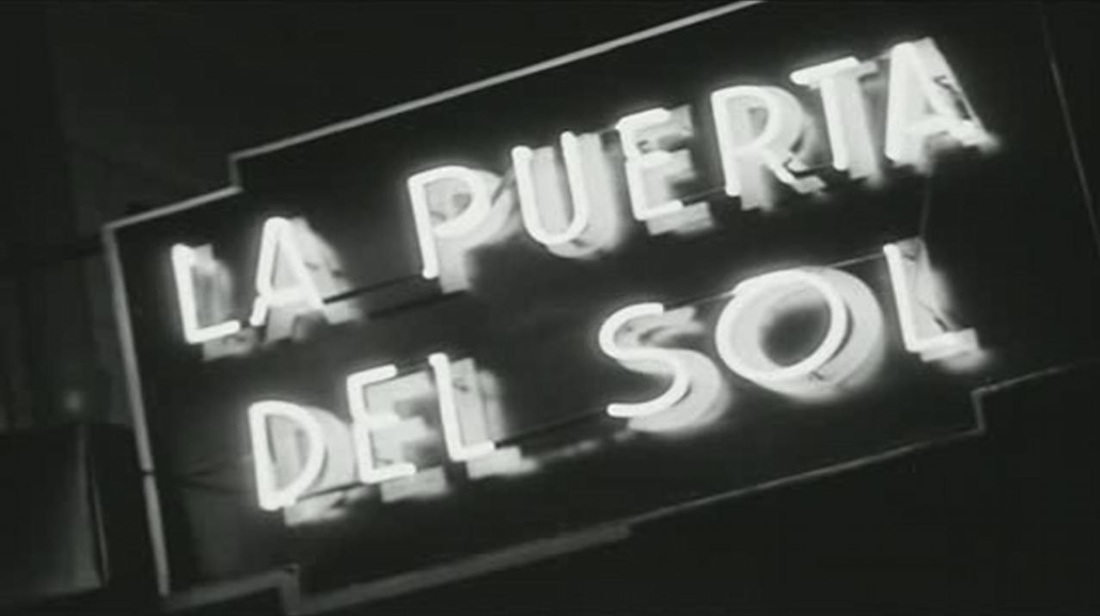

To the left, with a sign reading 'Cuisine bourgeoise', is the restaurant 'Chez Bouche', the studio-constructed interior of which is the first place shown in the film, after the credits have run over a panoramic view of the butte Montmartre and the place Blanche:

|

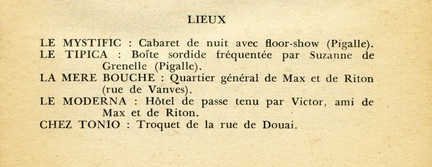

In cutting from a view of the Moulin Rouge to the interior of the restaurant, it is implied that the restaurant is somewhere thereabouts. The novel puts Chez Bouche across town, in the 15e (the rue de Vanves is now the rue Raymond Losserand), as you can see from the list of key locations that Albert Simonin puts on the first page.

|

Save for Bouche's restaurant, these are all in Pigalle, establishing straightway a topographical opposition. One of the things excised by Becker from Simonin's novel is its detailed preoccupation with place, so that topographical oppositions are established simply by visual difference, or the time it takes to journey from one place to another. There is one real and identified location preserved in the film, the junction of the rue Victor Massé and the rue Frochot, in Pigalle:

This nightclub is a principal location for the film, marking its underworld milieu on the map. The Mystific is an invented name, but its exterior is unmistakable thanks to the Hokusai-inspired stained glass window. The Frochot café next door confirms the identification as 2 rue Frochot. The ornamental window belonged to Le Shanghai, which had recently closed. A year after Becker's shoot, the space would become famous as the Théâtre en Rond de Paris.

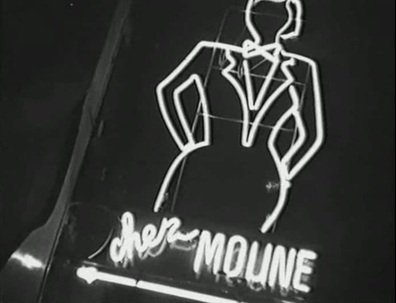

The only functioning club here at the time of the shoot was Le Fétiche, one of the area's best-known gay clubs. In Becker's film, the locale is turned straight by the added neon sign in the street - I'm assuming naked women connote a hetero establishment, on the basis that the hetero club Pigall's has a naked woman as sign, whereas lesbian club Chez Moune le Fétiche (created by a manager from Le Fétiche in the rue Frochot) has a dressed woman as sign:

The only functioning club here at the time of the shoot was Le Fétiche, one of the area's best-known gay clubs. In Becker's film, the locale is turned straight by the added neon sign in the street - I'm assuming naked women connote a hetero establishment, on the basis that the hetero club Pigall's has a naked woman as sign, whereas lesbian club Chez Moune le Fétiche (created by a manager from Le Fétiche in the rue Frochot) has a dressed woman as sign:

The club in Grisbi is heterosexualised also by the semi-naked women on the dance floor and the posters in the club owner's office:

Apart from Jeanne Moreau and Dora Doll (below left), who do a strikingly amateurish number together, the dancers in this fake cabaret look like a professional ensemble, but I haven't been able to work out yet from which real establishment they were acquired:

The year before, Jean Boyer had borrowed the dancers of the Nouvelle Eve (25 rue Fontaine, 9e) for his film Femmes de Paris but, whereas they had received a credit, the dancers in Grisbi are not acknowledged:

The doorman of Le Mystific is definitely a fake doorman, since he was played by the director's son Jean (and not Gérard Blain, as some filmographies claim):

|

The interiors of the club are studio constructions, but Becker uses more of the real exterior than just this entrance. To the left in the shot above is the rue Frochot, a short street packed with clubs and bars. Here it is, left, in the Grisbi-influenced Quand la femme s'en mêle (Yves Allégret 1957), a few doors up from the club in Grisbi. |

To the right of the Mystific, out of frame, is the avenue Frochot, a quiet, almost rural street with individual villas, quite uncharacteristic of Pigalle - though Django Reinhardt lived here, local to the clubs in which he performed.

Jean Renoir also lived here, at number 7, and some commentators on Grisbi report that Becker filmed from a window in Renoir's house (Renoir was something of a mentor to Becker). I can't quite work out if the story is true, since Renoir's house was across the avenue from the club, and the only shots from a window look onto the avenue from the club side. Whatever the case, Becker makes the most of this very different aspect of Pigalle:

Jean Renoir also lived here, at number 7, and some commentators on Grisbi report that Becker filmed from a window in Renoir's house (Renoir was something of a mentor to Becker). I can't quite work out if the story is true, since Renoir's house was across the avenue from the club, and the only shots from a window look onto the avenue from the club side. Whatever the case, Becker makes the most of this very different aspect of Pigalle:

Another director for whom Renoir was a kind of mentor also filmed in this avenue. This, in Les 400 coups, is Renoir's house:

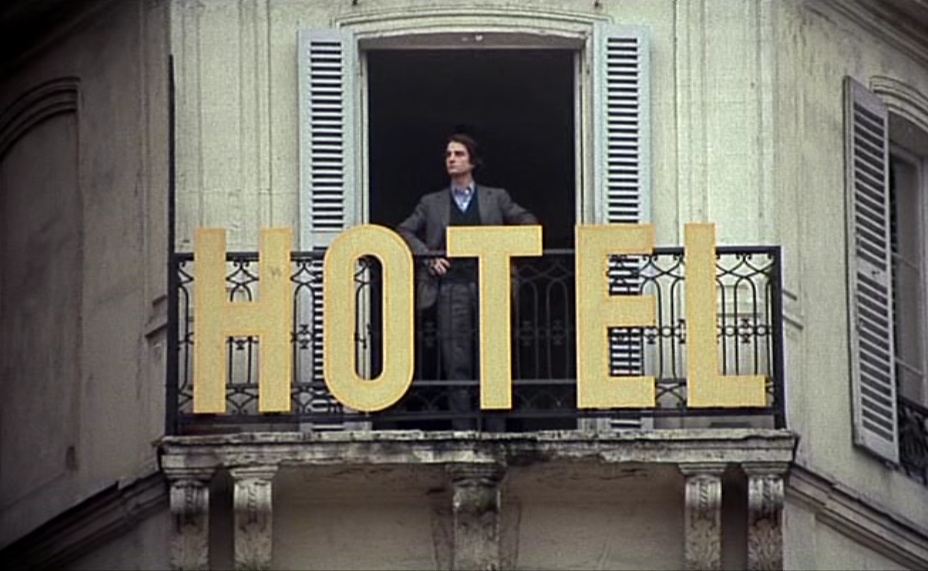

Other than in the opening panorama over Montmartre and the use here of the rue and avenue Frochot, Grisbi is generally reticent about its Parisian topography. One of the characters lives at the Hotel Moderna, a fictional name given in the novel, used to disguise a hotel on the rue Rodier, 9e, towards the eastern edge of Pigalle:

Two streets, that I haven't been able to identify, are given false names, the rue Alphonse Allais and the rue des Détroits:

The address or locale of Bouche's restaurant is not mentioned at all.

As we have seen, the location used for that street is the rue Blomet. Until the film's last exterior sequence we only see the street at night. With this little detail and in this kind of light, nothing says that the street here hasn't been constructed in a studio:

As we have seen, the location used for that street is the rue Blomet. Until the film's last exterior sequence we only see the street at night. With this little detail and in this kind of light, nothing says that the street here hasn't been constructed in a studio:

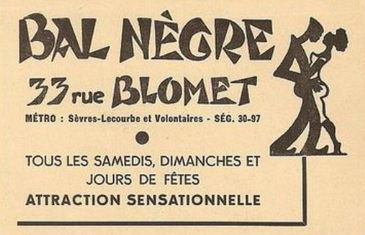

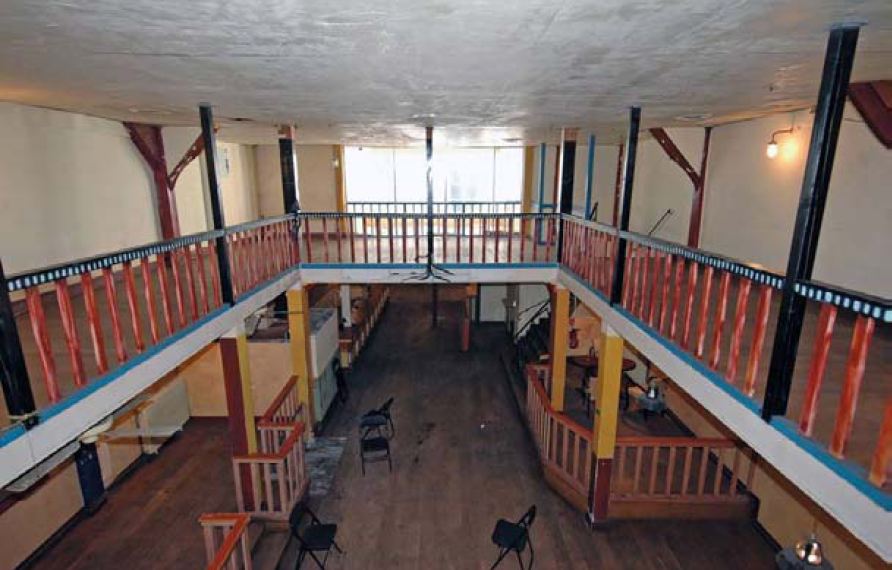

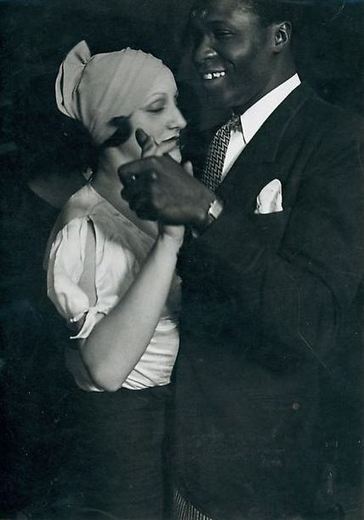

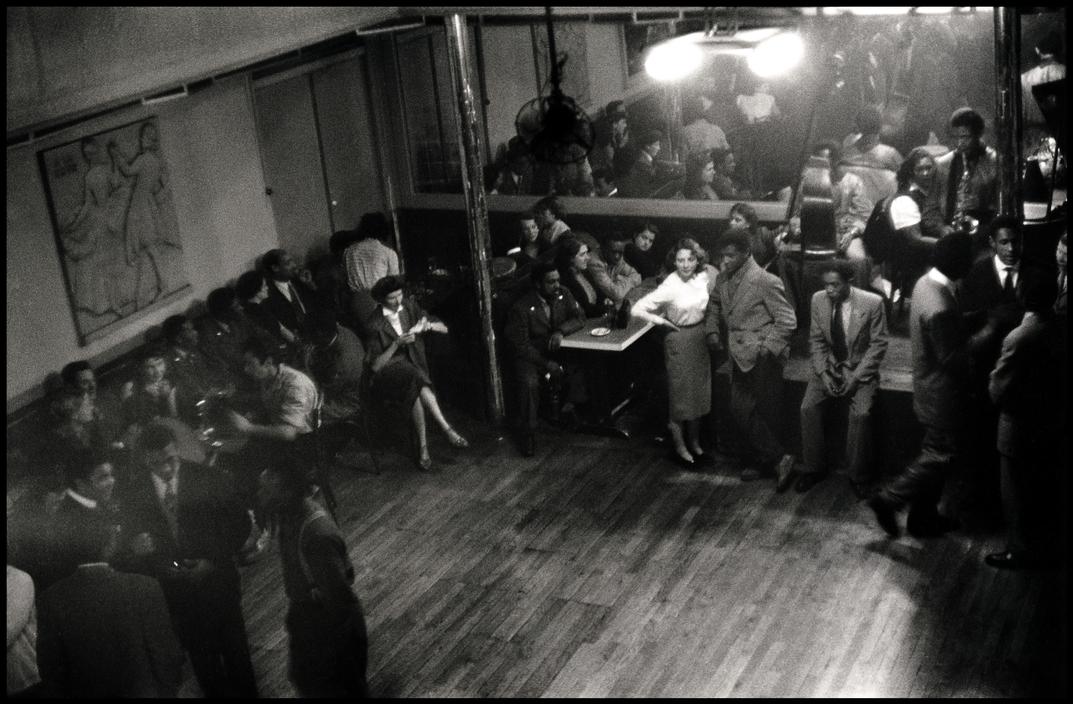

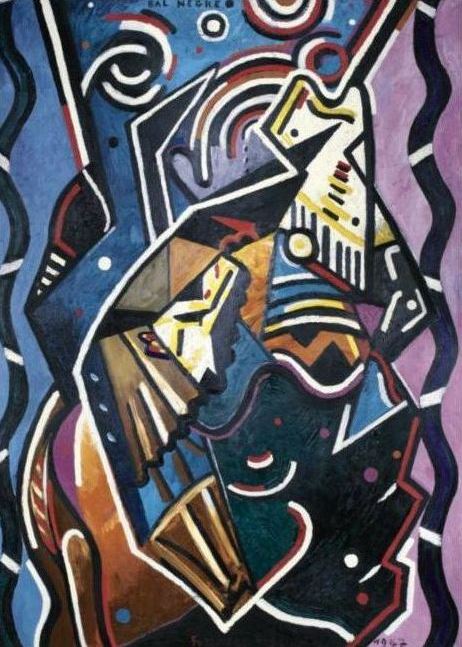

Or almost nothing. Just above the door by which the two men have left is a sign that reads, on closer examination, 'Bal Nègre'. At 33 rue Blomet, in the mid-1920s, was created the Bal Blomet, a social space for West Indians in Paris that soon became a fashionable spot for all kinds of nightclubbing Parisians, and was also known as the Bal Doudou, the Bal Colonial or the Bal Nègre. Its heyday was the 1930s, but it was broadly fashionable again postwar until it closed down in 1962. Its history is told here (in French).

(The card above right was offered for sale at auction in 2009 - see here - as dating from 1920, which is of course impossible. I'd say that it was from the 1950s, like the sign above the door in Touchez pas au grisbi.)

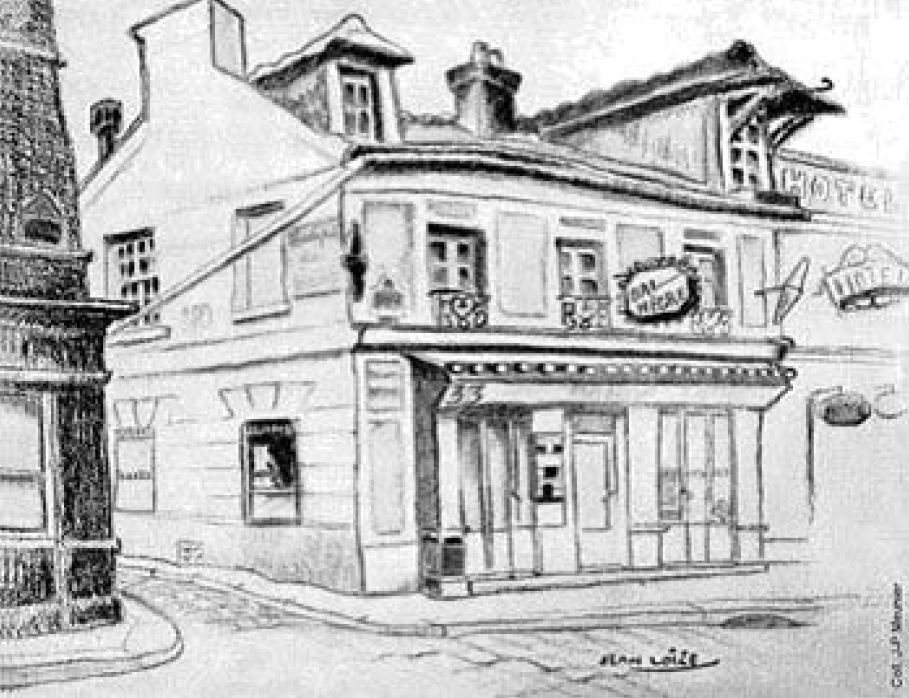

The site has recently become a matter of particular interest to local historians because the premises have been under threat of demolition - the threat is lifted, and the place will become a cultural centre. You can read here, pp 14-16, in French, a report from May 2010 by the Commission du Vieux Paris on this historic site. The pictures below are from this report:

The site has recently become a matter of particular interest to local historians because the premises have been under threat of demolition - the threat is lifted, and the place will become a cultural centre. You can read here, pp 14-16, in French, a report from May 2010 by the Commission du Vieux Paris on this historic site. The pictures below are from this report:

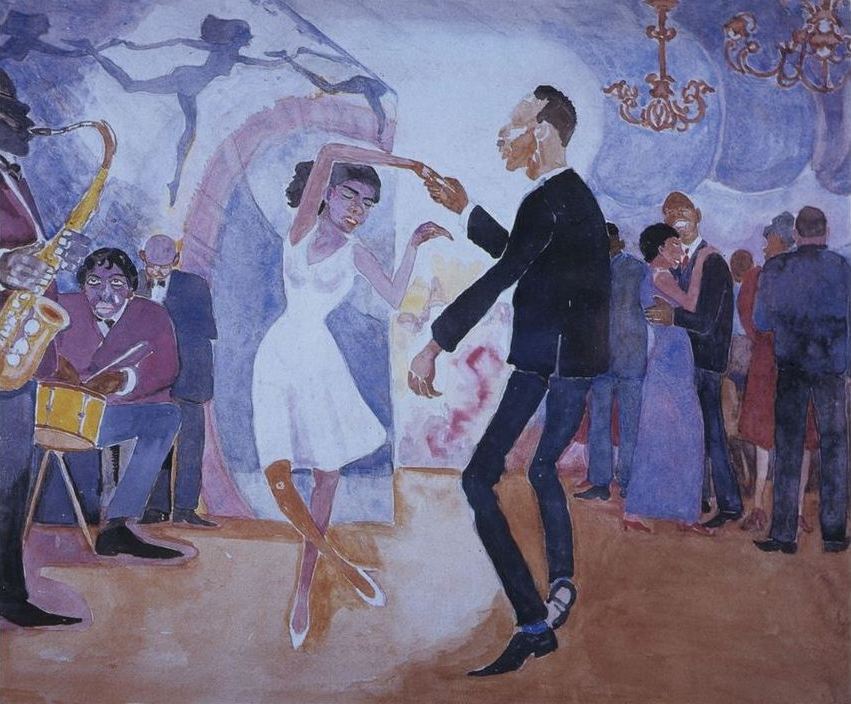

The Bal Blomet is important in the history of Antillean culture in Paris, of jazz more broadly, and has left its mark in the history of painting. Below is Palmer Hayden's Bal jeunesse, inspired by the Bal Blomet after visits in 1927:

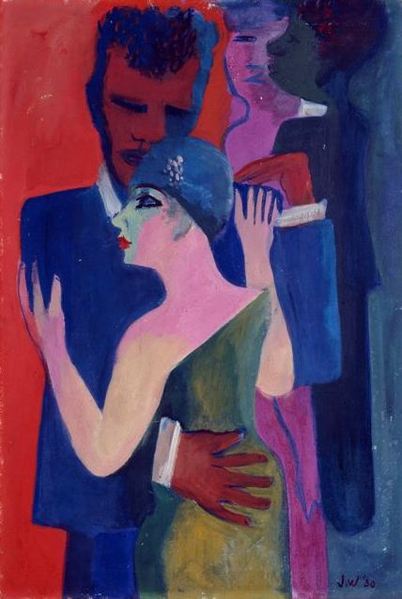

The two 'Bal Nègre' paintings above are by Milivoy Ulezac (c.1927) and Jan Wiegers (1930). You can see other artists' impressions here. Foujita and Mondrian were habitués in the '20s and '30s, as were poets Robert Desnos and Philippe Soupault, and the dancehall was photographed, famously, by Brassaï in 1932:

As unfeasible as the description of Sartre on the dance floor sounds, it is well-documented that he frequented the place alongside Beauvoir and Merleau-Ponty. It is here, for example, that he met Juliette Greco.

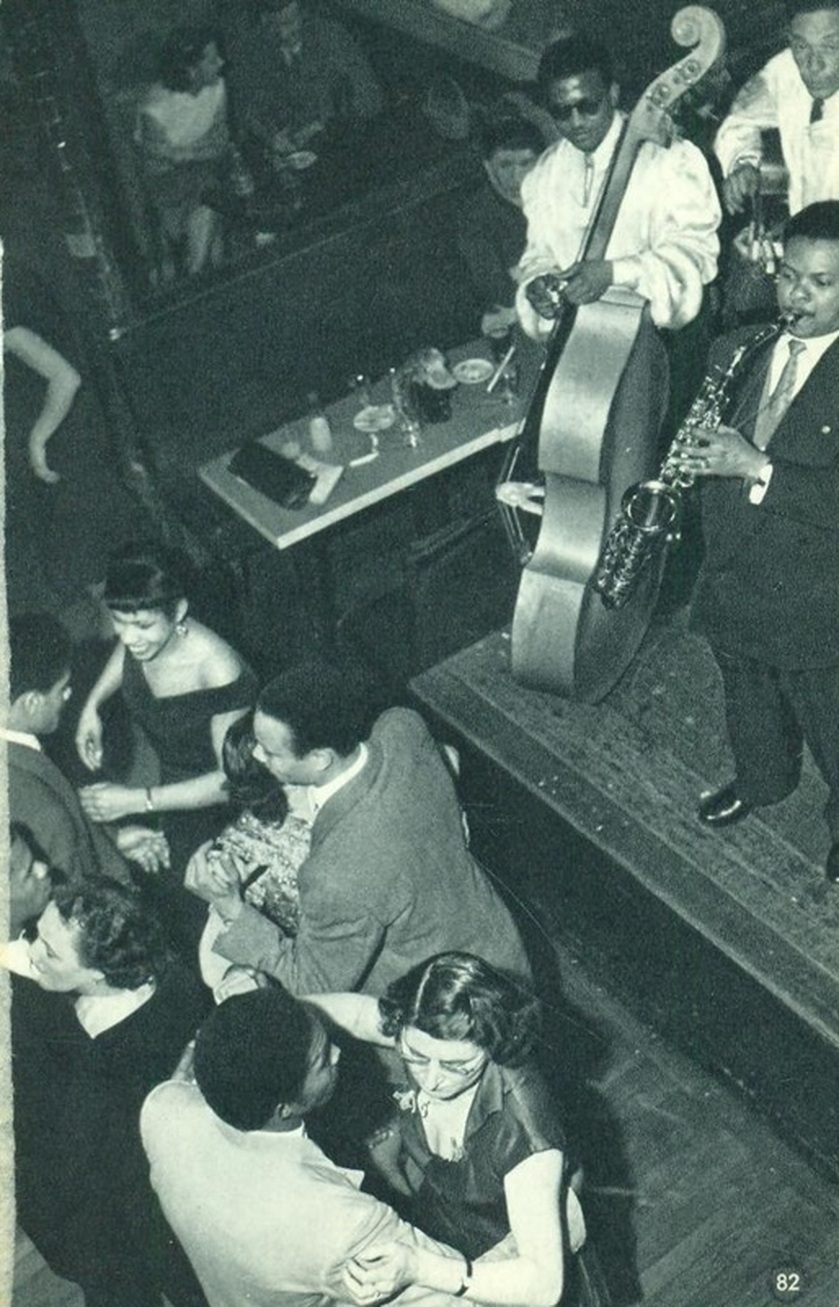

The photographers returned. Elliott Erwitt went up to the balcony for this plunging view:

The photographers returned. Elliott Erwitt went up to the balcony for this plunging view:

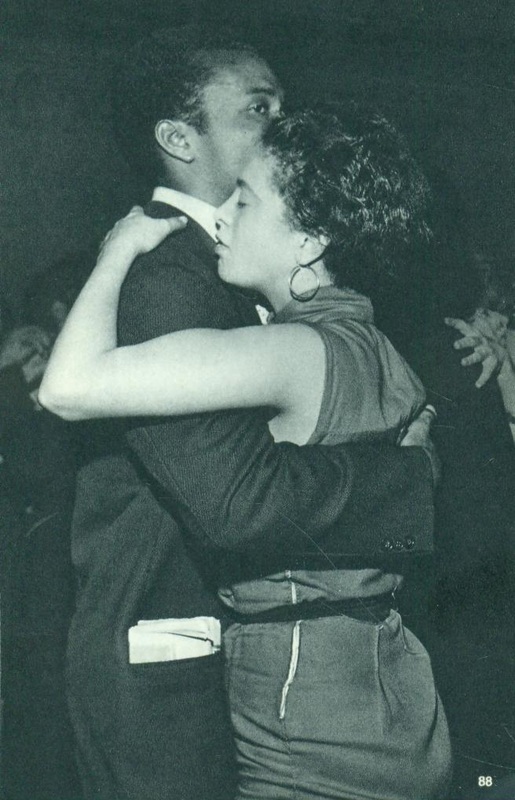

Robert Doisneau and Daniel Frasnay came closer to the dancing couples, in the manner of Brassaï in the 1930s:

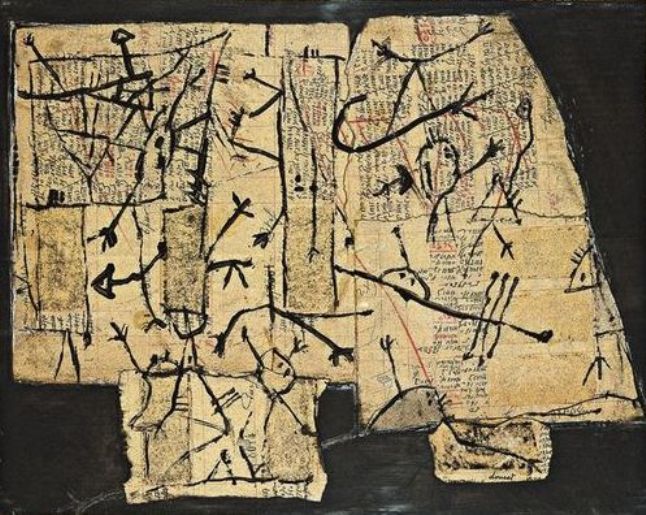

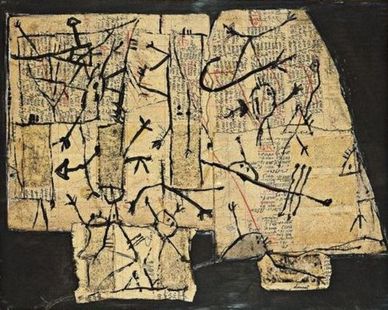

The art inspired by the Bal changed in emphasis, as these pieces by Francis Picabia in 1947 and Jacques Doucet in 1948 illustrate:

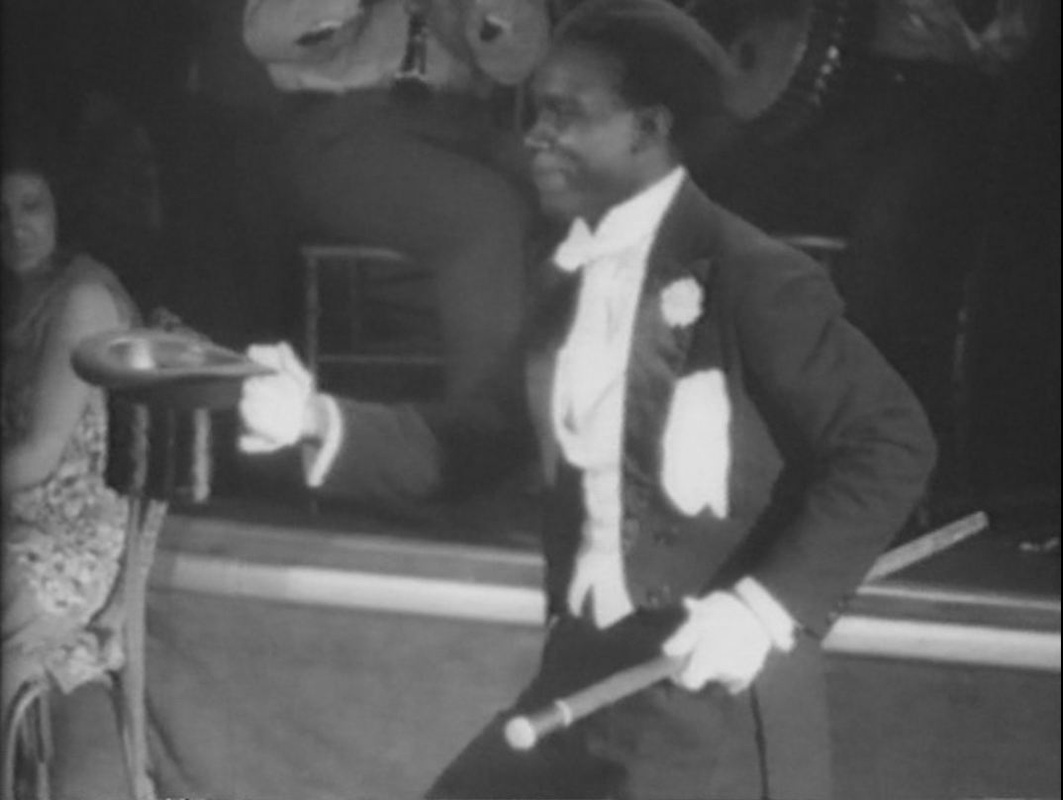

Unlike painters and photographers, very few filmmakers seem to have exploited this locale. In 1930 Jean Grémillon staged the climax of La Petite Lise (1930) at the Bal Nègre, though he reconstructed the look and ambience of the rue Blomet dancehall in the studio, importing musicians, dancers and regular clientele to ensure authenticity:

Ernest Léardée tells us that the dancer featured was Félix Ardinet, aka Bam Bam, and not Josephine Baker's sometime partner Joe Alex, as claimed on IMDB. Léardée, the orchestra leader at the Bal Blomet, describes at great length in his memoirs the process of importing and reconstructing the Bal in the studios at Joinville, and takes great pride in the authenticty of the result.

By contrast, Julien Duvivier represented the Bal Nègre in his 1932 Allo Berlin? Ici Paris, another studio reconstruction but without the same attention to authentic detail - the music and dancing especially are all wrong:

By contrast, Julien Duvivier represented the Bal Nègre in his 1932 Allo Berlin? Ici Paris, another studio reconstruction but without the same attention to authentic detail - the music and dancing especially are all wrong:

I have found the Bal Blomet in one other film, the 1931-set Henry and June (1990):

Again a studio reconstruction. The look isn't quite right and the music is wrong, which is disappointing given the film's fetish of exact reconstruction, for example in the scene showing Brassai taking a photograph, in which not only the subject being photographed assumes the pose of the subject of the original photograph, but the actor playing Brassai also assumes a pose from a photograph of Brassai (see here).

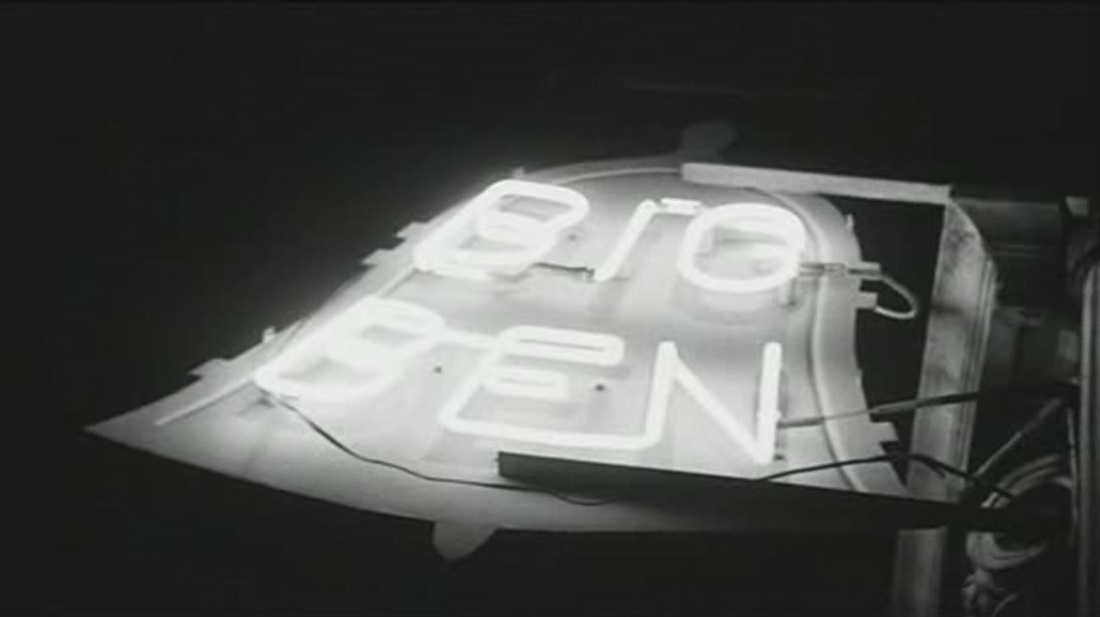

The dancehall at 33 rue Blomet was an exciting and significant place, but none of that excitement or significance is in evidence when Becker films there in 1954. The space itself, with its large galleried hall beyond the café area fronting the street, is ignored, since Becker constructs a fake interior for Bouche's restaurant to alternate with shots of the real street outside. He even has views from within the studio interior purporting to show the street beyond, and matches the backdrop of the street beyond with views of the real street by ensuring that in both we see the neon sign indicating a (fake) restaurant across the street, Chez Victor. This device doesn't quite work, in that when the sign is positioned in the real street the last letter of the name Victor doesn't light up, whereas when we see the sign from within Bouche's restaurant, it does:

The dancehall at 33 rue Blomet was an exciting and significant place, but none of that excitement or significance is in evidence when Becker films there in 1954. The space itself, with its large galleried hall beyond the café area fronting the street, is ignored, since Becker constructs a fake interior for Bouche's restaurant to alternate with shots of the real street outside. He even has views from within the studio interior purporting to show the street beyond, and matches the backdrop of the street beyond with views of the real street by ensuring that in both we see the neon sign indicating a (fake) restaurant across the street, Chez Victor. This device doesn't quite work, in that when the sign is positioned in the real street the last letter of the name Victor doesn't light up, whereas when we see the sign from within Bouche's restaurant, it does:

The first of these pairings is from the beginning of the film, the second from about fifty minutes later, and in each pairing the shots are consecutive, so there isn't a realist explanation to be found as to why the 'R' of 'VICTOR' isn't always on. This is a minor point, I agree. More interesting perhaps, is the variation introduced in the later shot in the street, where the car is facing and drives off in the opposite direction from the one it had taken before. The second time the car goes the wrong way up a one-way street, though I don't think we can be expected to register the fact. (It is only at the end that we get a sense of the traffic on the rue Blomet.)

My question, in conclusion to this piece (finally), is a simple one: what is Becker doing here? Why come all the way to shoot on the rue Blomet, both by night and day, for basic views of an ordinary street? Why use the outside of so famous an establishment as the Bal Nègre, even allowing its sign to appear in frame, however briefly, when nothing associated with the Bal Nègre is to be associated with the film Touchez pas au grisbi? (I don't have an answer.)

Put differently, my question would be: Where's the jazz?

Becker was a big jazz fan, but only Le Rendez-vous de juillet, of his few films hitherto, had given him the opportunity to exploit that interest. The jazz in Le Rendez-vous de juillet was of a very specific kind, centred on Claude Luter's trad ensemble based at the Caveau des Lorientais in the 5e, and we might have thought he would be tempted by the chance to ring changes by using the Antillean jazz of the band at the Bal Nègre, led by Barel Coppet at the time.

Antillean jazz ensembles weren't incompatible with French noir, as Melville would show two years later in Bob le flambeur, when he installed Al Lirvat's Cigal's band in a Pigalle cabaret to accompany Isabelle Corey's erotic dance:

Put differently, my question would be: Where's the jazz?

Becker was a big jazz fan, but only Le Rendez-vous de juillet, of his few films hitherto, had given him the opportunity to exploit that interest. The jazz in Le Rendez-vous de juillet was of a very specific kind, centred on Claude Luter's trad ensemble based at the Caveau des Lorientais in the 5e, and we might have thought he would be tempted by the chance to ring changes by using the Antillean jazz of the band at the Bal Nègre, led by Barel Coppet at the time.

Antillean jazz ensembles weren't incompatible with French noir, as Melville would show two years later in Bob le flambeur, when he installed Al Lirvat's Cigal's band in a Pigalle cabaret to accompany Isabelle Corey's erotic dance:

(You can see another of Lirvat's ensembles at La Cigale here.)

As it is, the only band playing in Touchez pas au grisbi, at the Mystific, is an ensemble led by Jerry Mengo playing a kind of jazz so conventional as to pass unnoticed.

Becker certainly knew about the music in the rue Blomet. Four years before he had asked the painter Jacques Doucet to decorate in CoBrA-style the river-going automobile featured in Le Rendez-vous de juillet, and it was just at this time that Doucet, like Becker a jazz enthusiast, was spending time at the Bal Nègre:

As it is, the only band playing in Touchez pas au grisbi, at the Mystific, is an ensemble led by Jerry Mengo playing a kind of jazz so conventional as to pass unnoticed.

Becker certainly knew about the music in the rue Blomet. Four years before he had asked the painter Jacques Doucet to decorate in CoBrA-style the river-going automobile featured in Le Rendez-vous de juillet, and it was just at this time that Doucet, like Becker a jazz enthusiast, was spending time at the Bal Nègre:

Becker and crew must have shot the sequences in the rue Blomet on a weekday, when there was no crowd of existentialists to distract them, and no biguine-flavoured jazz from Barel Coppet and ensemble to tempt them:

|

One answer as to why Becker didn't go beyond the front door at 33 rue Blomet might be that he was deliberately avoiding the distinctive brilliance of the music being played there in order to avert any competition with Jean Wiener's score, the Grisbi theme around which the film was centred and on which a large part of its eventual success would depend. |

That explains why Becker didn't use the resources of the rue Blomet once he found himself there, but it doesn't explain why he went there in the first place. Just a coincidence, probably. I'll have to leave it at that.

Touchez pas au grisbi is still a fine film though it didn't use the music of Barel Coppet, despite filming right outside the Bal Nègre, just as Les Bonnes Femmes is a fine film though it didn't make any intertextual connections with Touchez pas au grisbi, despite filming right outside the Grisbi-Club.

Touchez pas au grisbi is still a fine film though it didn't use the music of Barel Coppet, despite filming right outside the Bal Nègre, just as Les Bonnes Femmes is a fine film though it didn't make any intertextual connections with Touchez pas au grisbi, despite filming right outside the Grisbi-Club.

References

- Patrice Bollon, Pigalle: le roman noir de Paris (Paris: 2004, Hoëbeke, 2004)

- Catherine Grant, 'Unsentimental education: on Claude Chabrol's Les Bonnes Femmes, video-essay at Film Studies for Free (June 2009)

- Jacques Robert, Paris By Night: a Tour of the Capital's Gay Pleasure Haunts (London: Charles Skilton Ltd, 1962 [1959])

- Ernest Léardée, Brigitte Léardée, Jean-Pierre Meunier, La Biguine de l'Oncle Ben's: Ernest Léardée raconte (Editions caribbéennes, 1989)

- Kristin Ross, Fast Cars Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the reordering of French culture (The MIT Press, 1996)

My research is indebted to the scholarship of musicologist Jean-Pierre Meunier.