a picture of great significance: Hitchcock's Susannah

In the course of his guided tour of the Bates house and motel, Hitchcock points to a picture on the wall of the parlour and says: 'Oh, by the way, this picture has great significance, because ...', but then he moves on to another room.

In the film itself we see the picture better, firstly as one of a number of objets:

In the film itself we see the picture better, firstly as one of a number of objets:

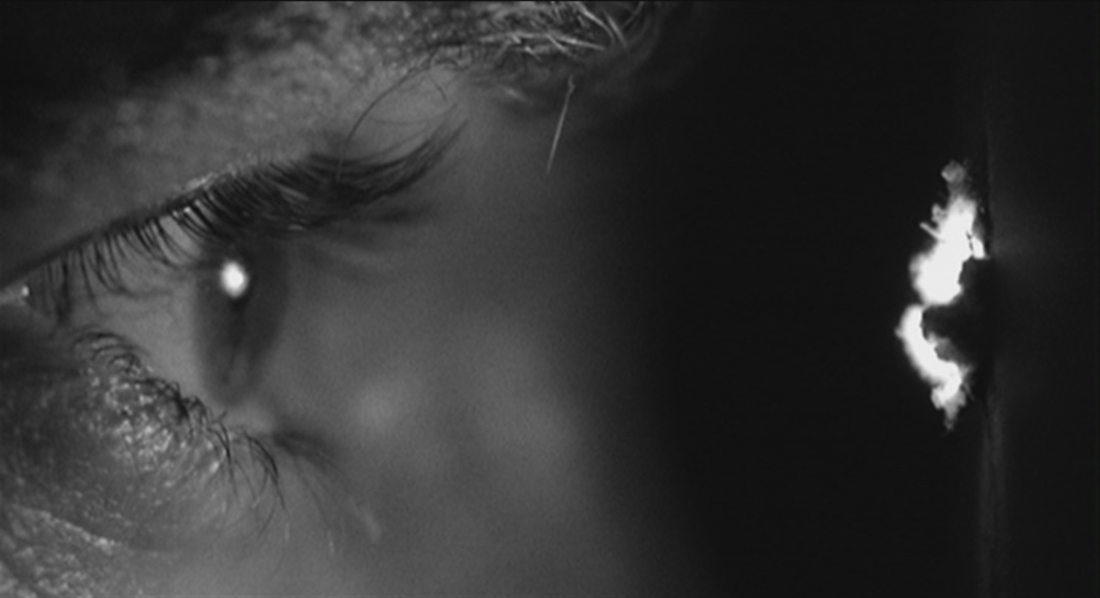

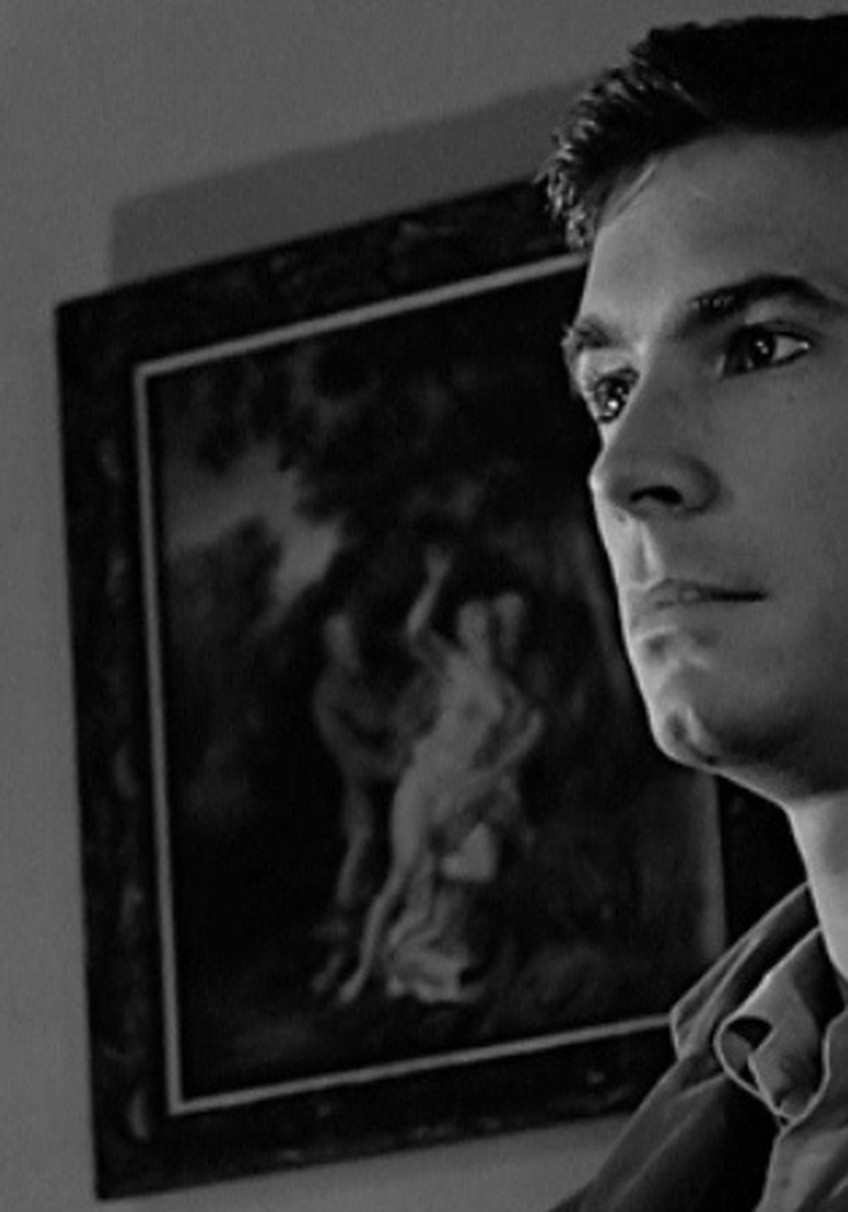

Then in close up, as Norman removes it to reveal a spyhole through which he will observe his victim:

The normal viewer identifies with Norman and wants to see what he sees:

The less normal viewer (that's us) wants to go back and look more closely at the picture that had hitherto obscured Norman's view:

|

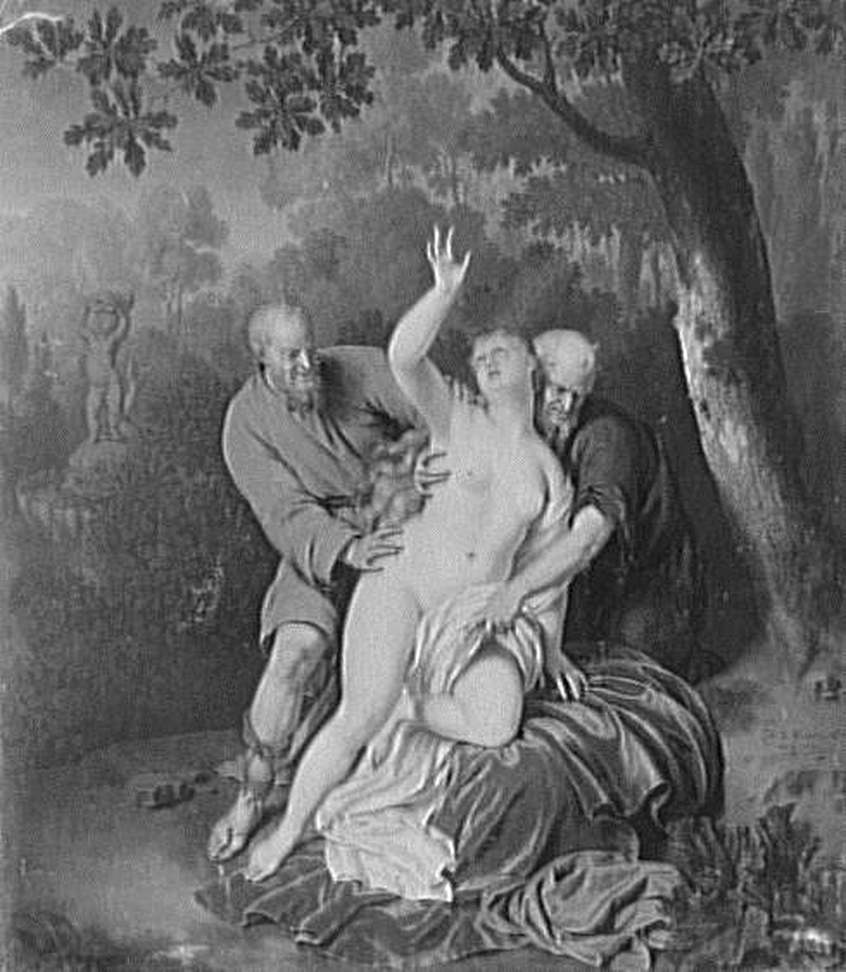

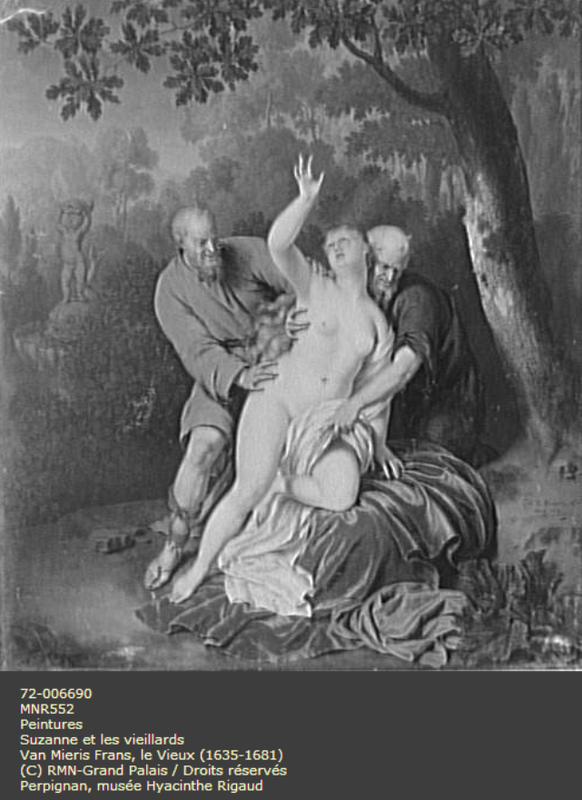

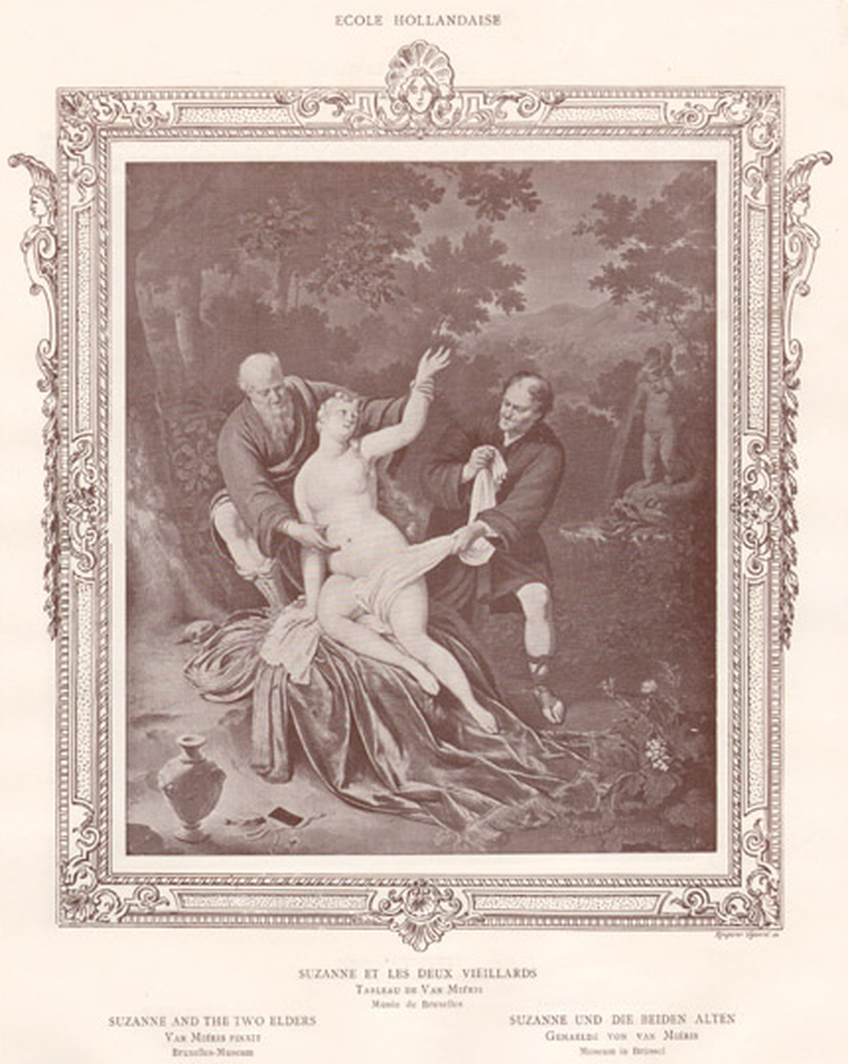

There has been consensus that the subject represented here is Susannah and the Elders, an episode from the Book of Daniel in which two old men spy on then attempt to rape a woman as she bathes. As far as I can gather no one has identified the artist, though I haven't gone through the entire corpus of Psycho scholarship to be sure. (My apologies if this post turns out to be redundant. [It turns out that it is - see note at the end of this post.]) As I was browsing through the images collected at the Réunion des Musées Nationaux, I happened across the above, the original of the image Hitchcock used. |

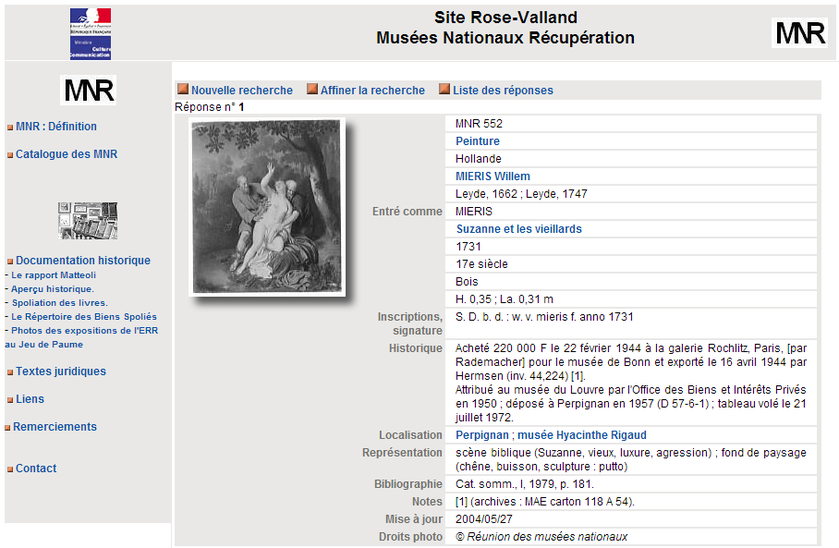

The artist is identified by the RMN as Frans van Mieris the Elder (1635-1681), and the work is said to be at the Hyacinthe Rigaud museum in Perpignan. However, another French government site attributes the painting to Willem van Mieris (1662-1747), Frans's youngest son:

The picture, measuring 35 by 31 centimetres, is dated to 1731 and Willem's signature is said to be apparent. After going to Bonn from Paris in 1944 it was given to the Louvre in 1950, and then to the museum in Perpignan in 1957. It was stolen from there in 1972.

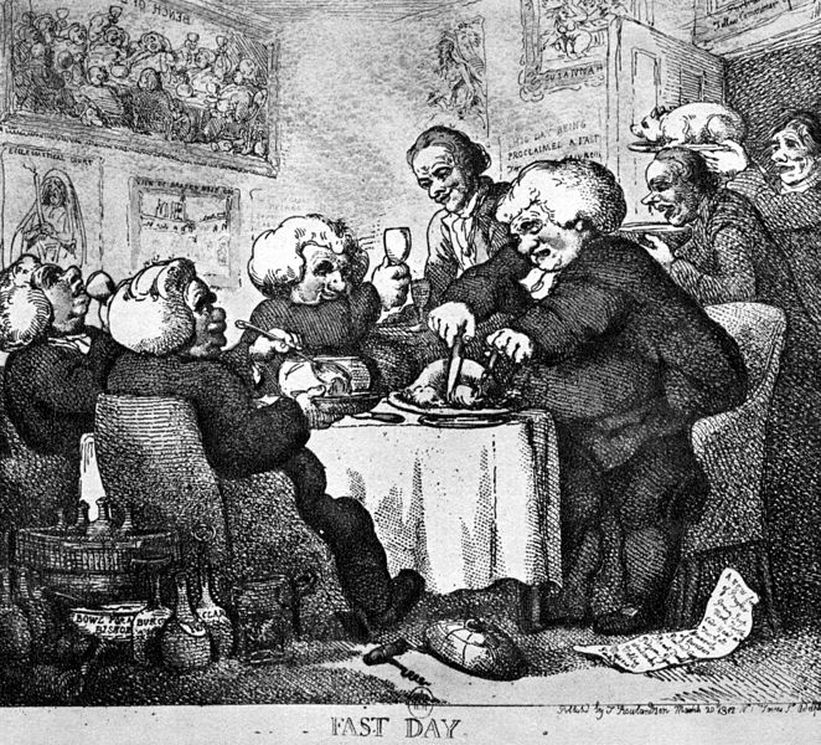

It would be interesting to know where Hitchcock found the image. Bill Krohn reports that Hitchcock had in his dining room a work by Thomas Rowlandson called Fast Day (1812), depicting clerics feasting. On the wall behind them is a painting of Susannah and the Elders, very like the Van Mieris:

Very like but not exactly. The old men do not appear to be touching Susannah yet, and she has her left arm raised rather than the right:

The Susannah in Rowlandson's print is a different version of the subject from the one in Psycho, not necessarily based on an existing work. It isn't, certainly, Rowlandson's own, less canonical version of the subject (see here).

(My thanks to Ken Mogg via Adrian Martin for pointing out Bill Krohn's report on the Rowlandsons owned by Hitchcock.)

(My thanks to Ken Mogg via Adrian Martin for pointing out Bill Krohn's report on the Rowlandsons owned by Hitchcock.)

You can see a wonderful collection of Susannah-related posts at ConSentido Proprio, here.

We know now who was the artist behind the Susannah in Norman Bates's parlour, but we await identification of other images in that room. The one on the right, below,is too dark for the subject to be clear, but it looks to me like another Susannah (If anyone can identify it, please let me know here):

We know now who was the artist behind the Susannah in Norman Bates's parlour, but we await identification of other images in that room. The one on the right, below,is too dark for the subject to be clear, but it looks to me like another Susannah (If anyone can identify it, please let me know here):

The picture on the left is Titian's Venus with a Mirror (1555):

Both the Titian and the Van Mieris were first identified several years ago - see the note at the end of this post.

Here are some other pictures glimpsed in Norman's parlour. They will be hard to identify, I think:

Here are some other pictures glimpsed in Norman's parlour. They will be hard to identify, I think:

Addition, 08.06.2016: 'laurent05735977' tweeted with the identification of one of these images, François Boucher's Vénus consolant l'Amour from 1751:

Merci Laurent.

A curious footnote to the Van Mieris identification is the large number of variations on the subject executed by the same artist. See, for example, this 'erotic' print from the 1890s, based on a Van Mieris painting, recently available from La Galerie Napoléon. This version is slightly different in composition from the Van Mieris that was in Perpignan:

The print locates this version in the Musée de Bruxelles, and the image conforms exactly to the description of the painting there from an 1895 guide, down to the detail that the old man on the left is holding her left hand in his left hand.

The variation below, dated 1704 and measuring 37 by 32 cm, sold at Christie's in Amsterdam in November 2010:

The variation below, dated 1704 and measuring 37 by 32 cm, sold at Christie's in Amsterdam in November 2010:

This version of the subject, in which Willem van Mieris renders an ivory sculpture by Francis van Bossuit, can be found at the Detroit Institute of Arts:

In November 1973 a picture called Suzanne and the Elders by Willem van Mieris was sold at Christie's in London. It is described as 'gouache sur parchemin', measuring 139 by 108 mm, signed and dated 1691. I haven't seen the catalogue yet to know if it is the same as any of the other versions we know, but the medium, small dimensions and early date suggest yet another different work. It appears to be the same work that sold at Sotheby's in Amsterdam in 1993.

In July 1992 a chalk on vellum Susannah (313 by 250 mm) by Van Mieris sold at Christie's in London.

In 2007, this Van Mieris, from the collection of the Duc de la Vallière, was sold at Sotheby's in Melbourne:

In July 1992 a chalk on vellum Susannah (313 by 250 mm) by Van Mieris sold at Christie's in London.

In 2007, this Van Mieris, from the collection of the Duc de la Vallière, was sold at Sotheby's in Melbourne:

That makes at least seven versions of the subject by Van Mieris, of which the one that until 1972 was in the Hyacinthe Rigaud museum in Perpignan was the one used by Hitchcock in Psycho.

I don't know enough to be able to explain Van Mieris's many variations on the theme, but for the time being I am just happy to know, finally, who exactly made a picture of such 'great significance'.

I don't know enough to be able to explain Van Mieris's many variations on the theme, but for the time being I am just happy to know, finally, who exactly made a picture of such 'great significance'.

Note (added January 4th 2013):

I have just discovered that the identification of the picture in Psycho had already been signalled two years ago by art historian Henry Keazor in the course of a lecture series on 'Hitchcock and the Arts' at the Universität des Saarlandes - for the forthcoming proceedings see here.

The first identifier was, I think, Jose Franco-Pereira, in his book INNERVATIONEN - Zur unbewussten Wahrnehmungsebene in Alfred Hitchcocks PSYCHO, published in 2001 (see here). Franco-Pereira also identifies the painting by Titian.

I have just discovered that the identification of the picture in Psycho had already been signalled two years ago by art historian Henry Keazor in the course of a lecture series on 'Hitchcock and the Arts' at the Universität des Saarlandes - for the forthcoming proceedings see here.

The first identifier was, I think, Jose Franco-Pereira, in his book INNERVATIONEN - Zur unbewussten Wahrnehmungsebene in Alfred Hitchcocks PSYCHO, published in 2001 (see here). Franco-Pereira also identifies the painting by Titian.

A further correction:

Henry Keazor has written to tell me that the first identifier of the Van Mieris was Barbara Stelzner-Large in her article ‘Zur Bedeutung der Bilder in Alfred Hitchcocks Psycho’, published in Helmut Korte & Johannes Zahlten (eds), Kunst und Künstler im Film (Hameln 1990), pp.121-133.

So I have to acknowledge that, like Jean-Pierre Léaud's father in Masculin-Féminin, I have simply re-discovered why the earth goes around the sun, centuries after Galileo.

Henry Keazor has written to tell me that the first identifier of the Van Mieris was Barbara Stelzner-Large in her article ‘Zur Bedeutung der Bilder in Alfred Hitchcocks Psycho’, published in Helmut Korte & Johannes Zahlten (eds), Kunst und Künstler im Film (Hameln 1990), pp.121-133.

So I have to acknowledge that, like Jean-Pierre Léaud's father in Masculin-Féminin, I have simply re-discovered why the earth goes around the sun, centuries after Galileo.