1/ Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-98)

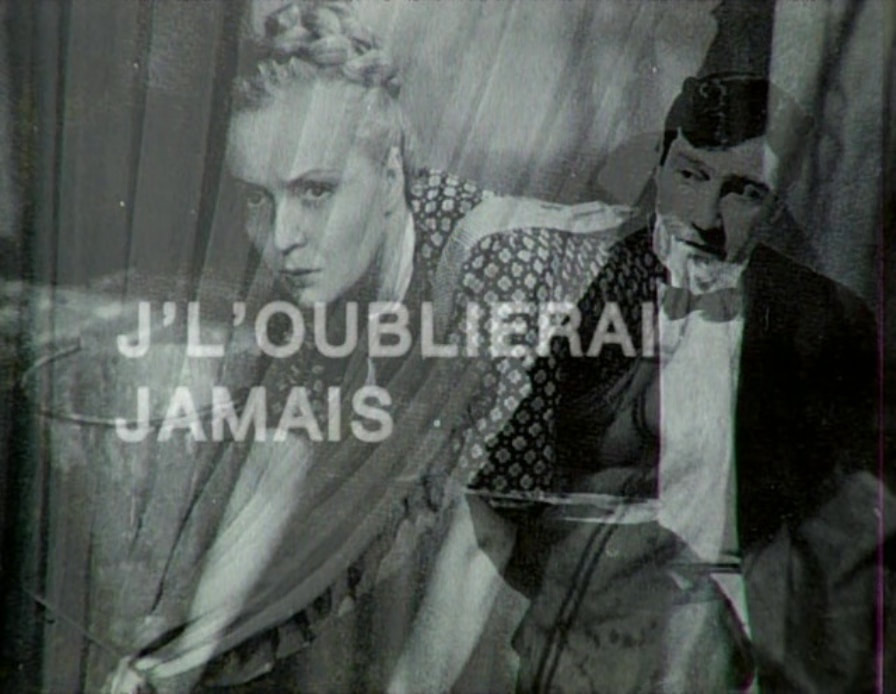

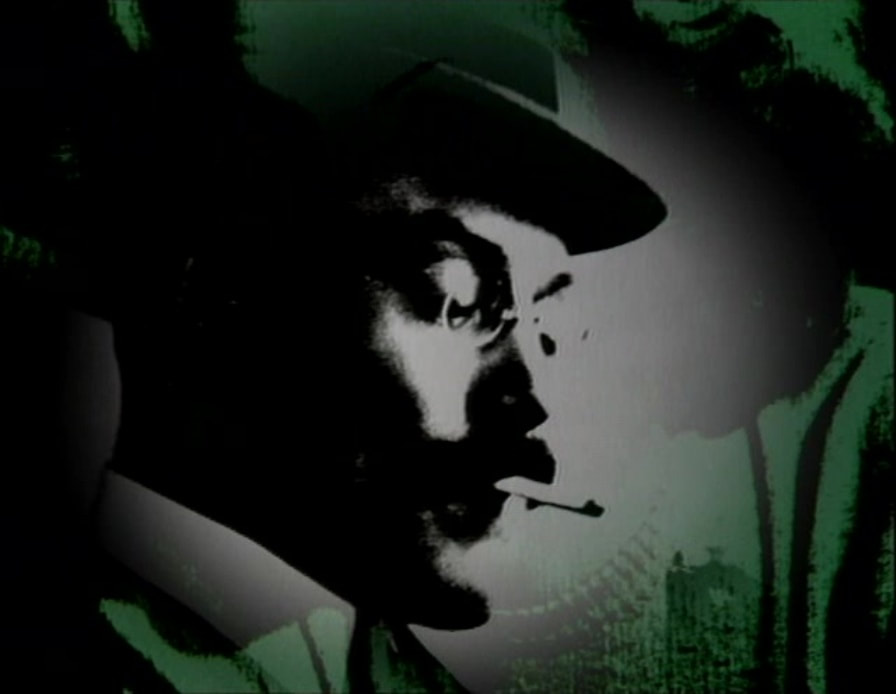

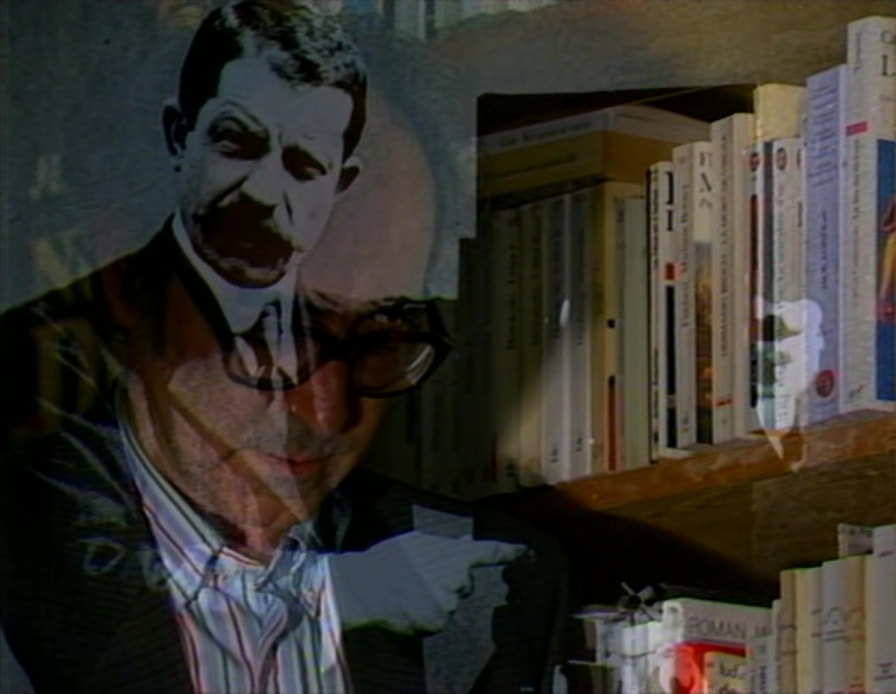

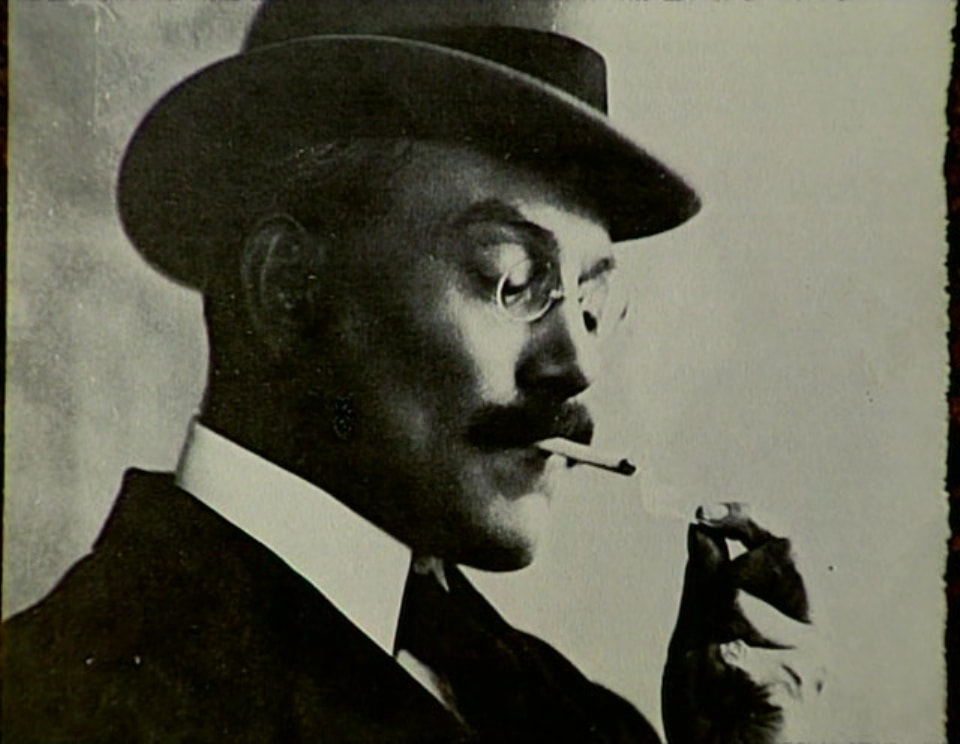

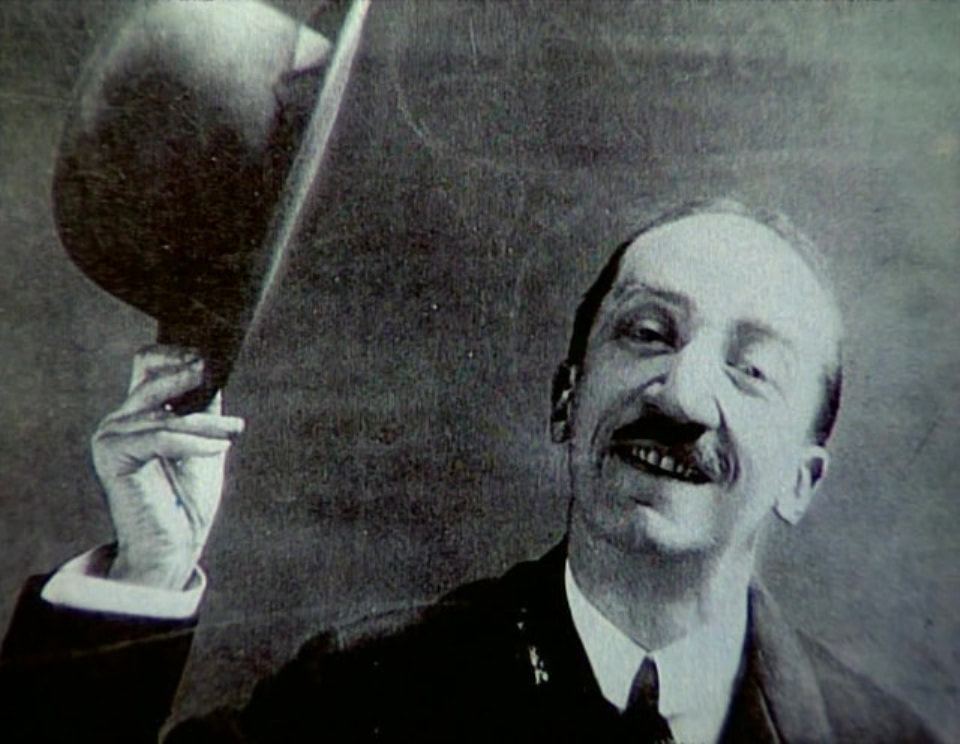

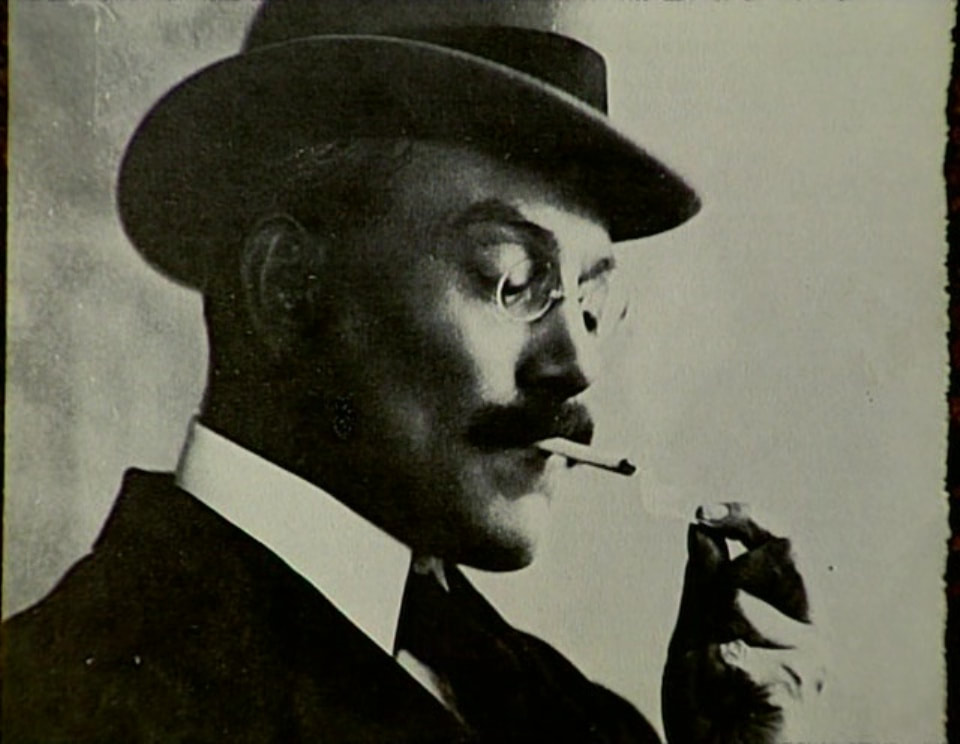

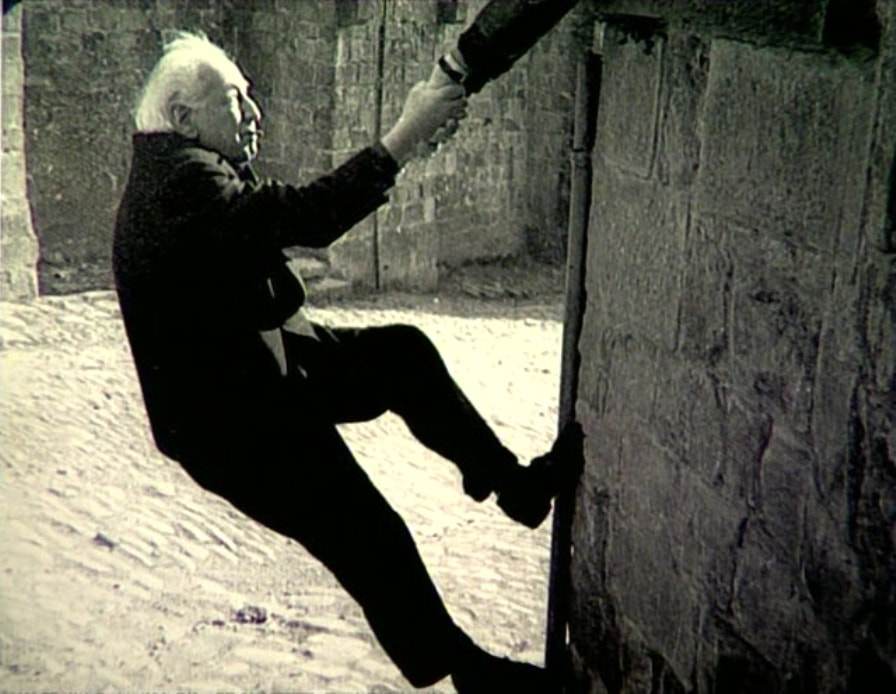

Godard's Histoire(s) du cinéma were completed in 1998 and presented as a co-production with Gaumont, a company with a significant place in the history of cinema, from 1896 onwards. Though the story of cinema's beginnings that Godard tells in Histoire(s) is dominated by pre-cinema and then by Lumière and Méliès, a place is accorded to the Gaumont company in part 1B through images of its founder Léon Gaumont and of Louis Feuillade, head of production at Gaumont after 1907:

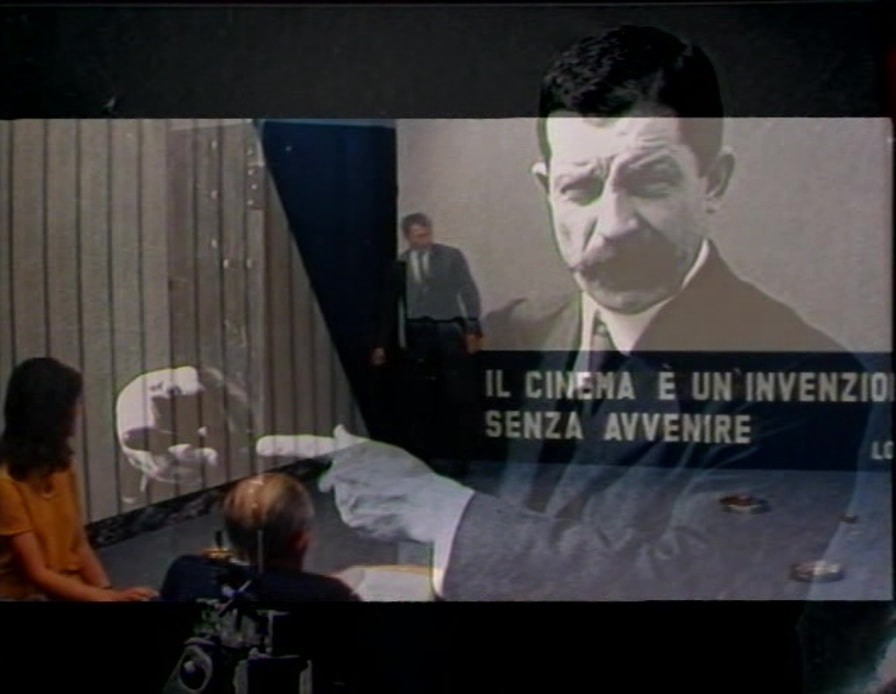

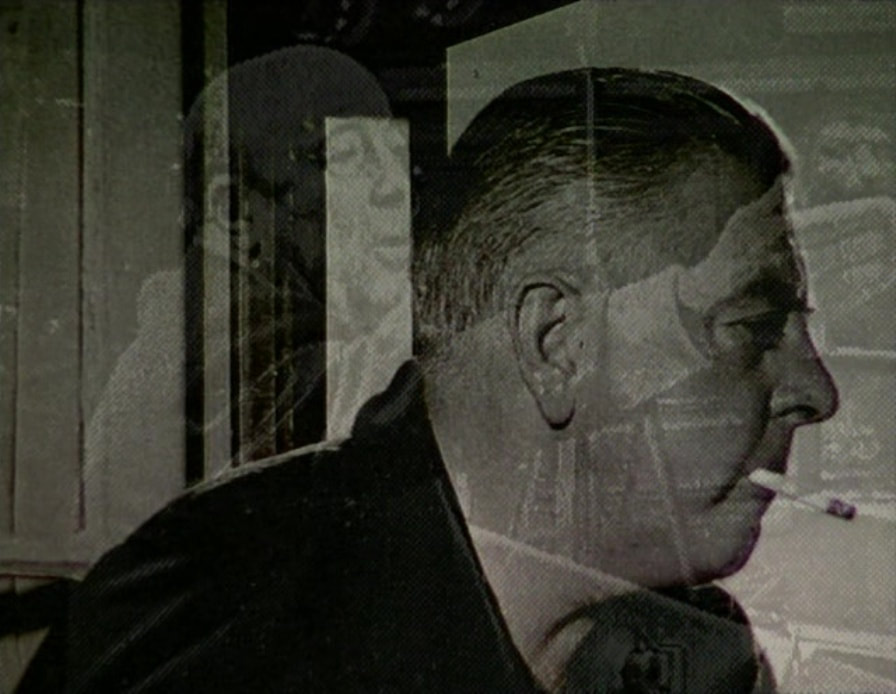

Feuillade's photograph is superimposed on an image from Bergman's Prison (1948), where a couple each side of a projector are watching a pastiche of an early comedy. The image of Gaumont and a camera is presented in several complex combinations with other images, most spectacularly with a shot from Le Mépris (1963), where his image appears to be on the screen in the viewing room at Cinecitta, above an Italian translation of the famous phrase attributed to Antoine Lumière regarding the cinema's want of a future:

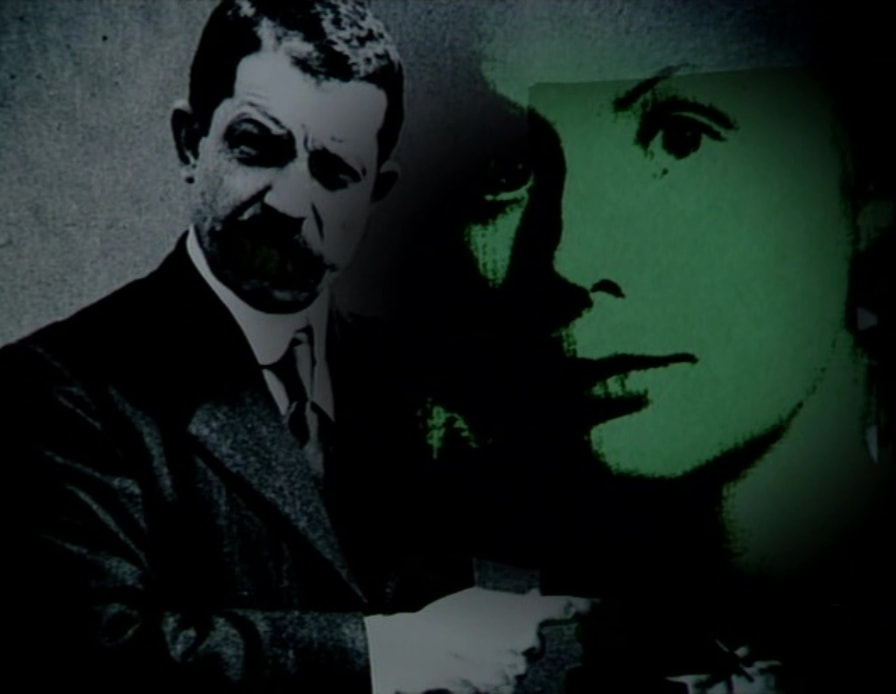

The image has been reversed so that Gaumont's face appears on the screen. When it is used again two minutes later the reversal is reversed:

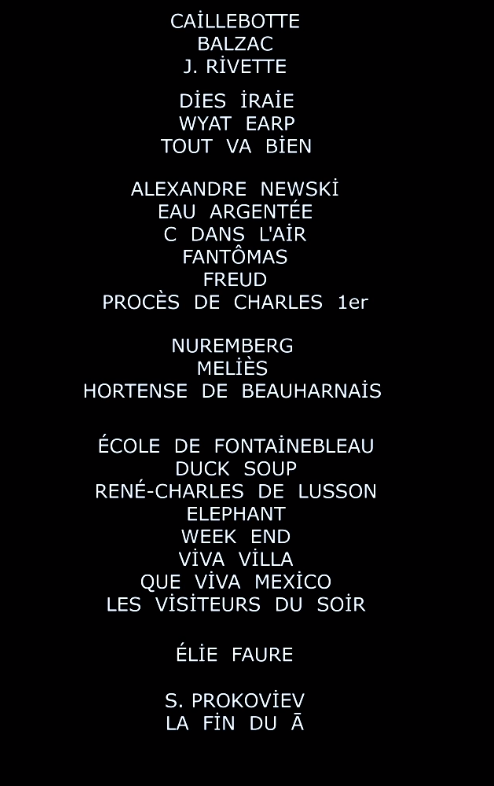

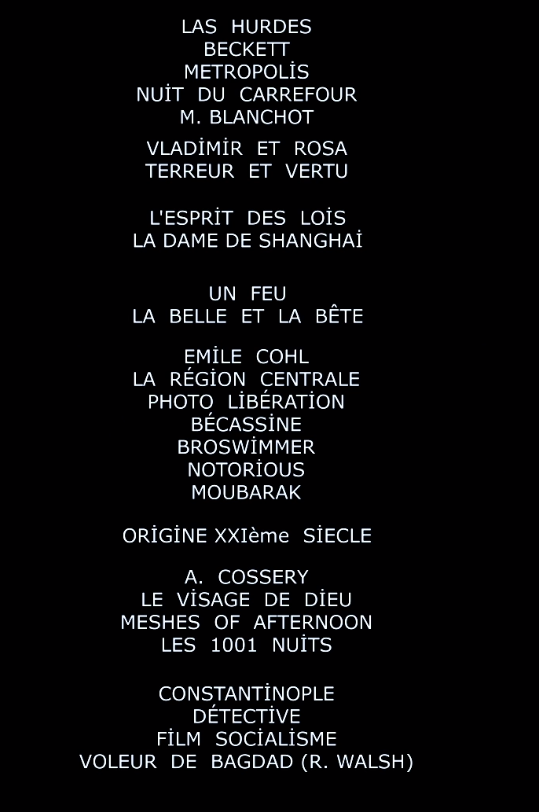

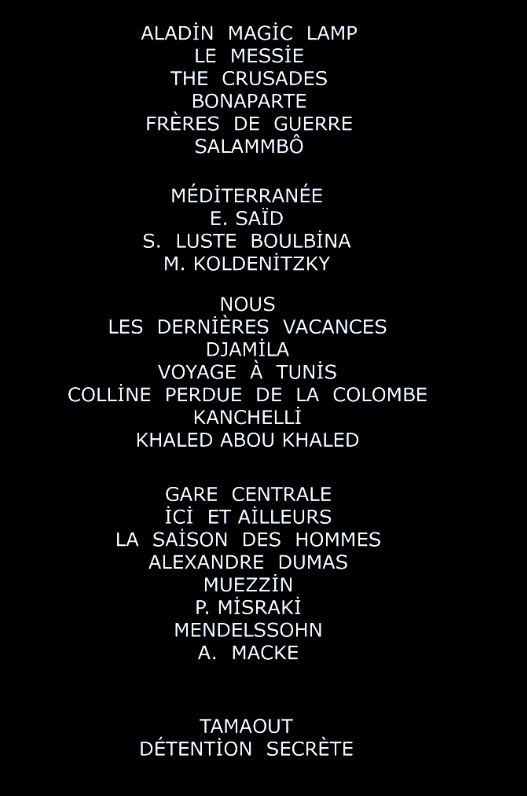

As well as these montages binding a founding father of cinema to images of its future, the name of Gaumont appears as a credit in each of the eight episodes of Histoire(s) du cinéma, always at the beginning and, after the first two, also at the end:

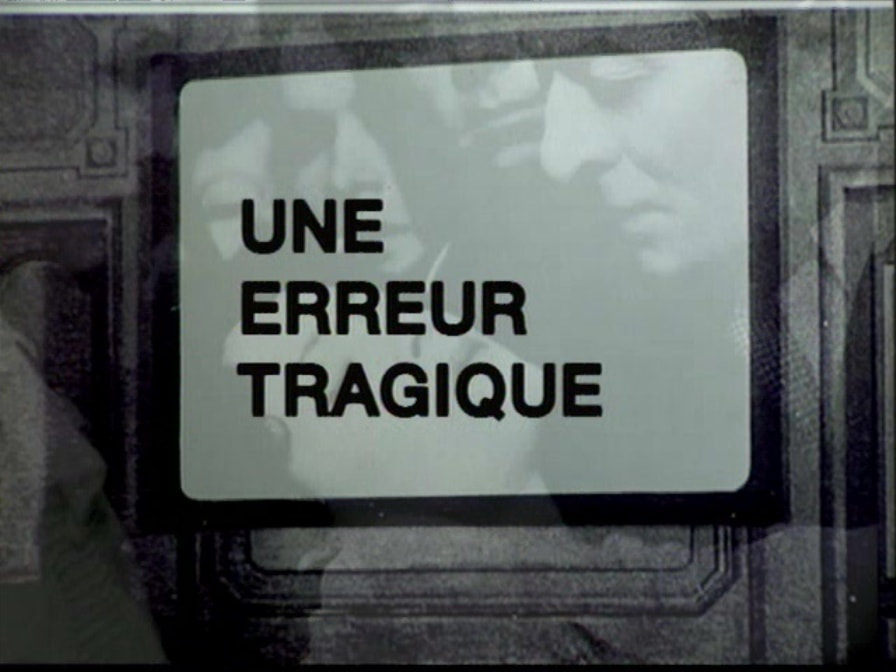

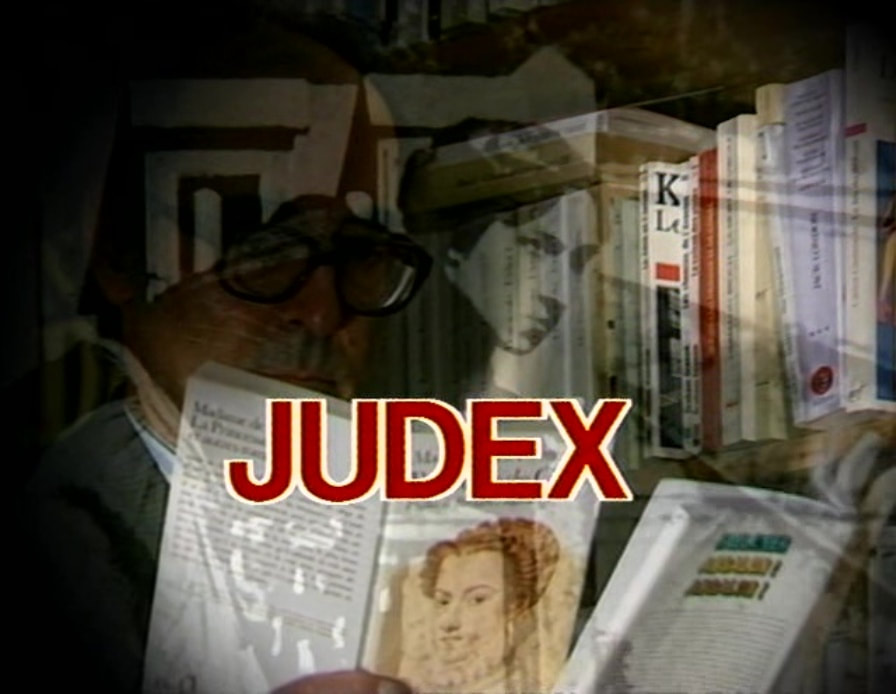

There are also mentions of or extracts from four films by Feuillade - Erreur tragique (1913), Fantômas (1913), Judex (1916) and Vendémiaire (1918):

There is, however, in the four hours and twenty-three minutes of Histoire(s) du cinéma, no image of Feuillade's predecessor Alice Guy, nor mention of her name or films. Her significance as the initiator of film production at Gaumont, and more generally as an innovator of story-telling in film, is not a story Godard tells.

As is made very clear in Pamela Green's new documentary Be Natural: the Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché, her effacement from cinema history is a long-standing and ongoing wrong that is only now being redressed.

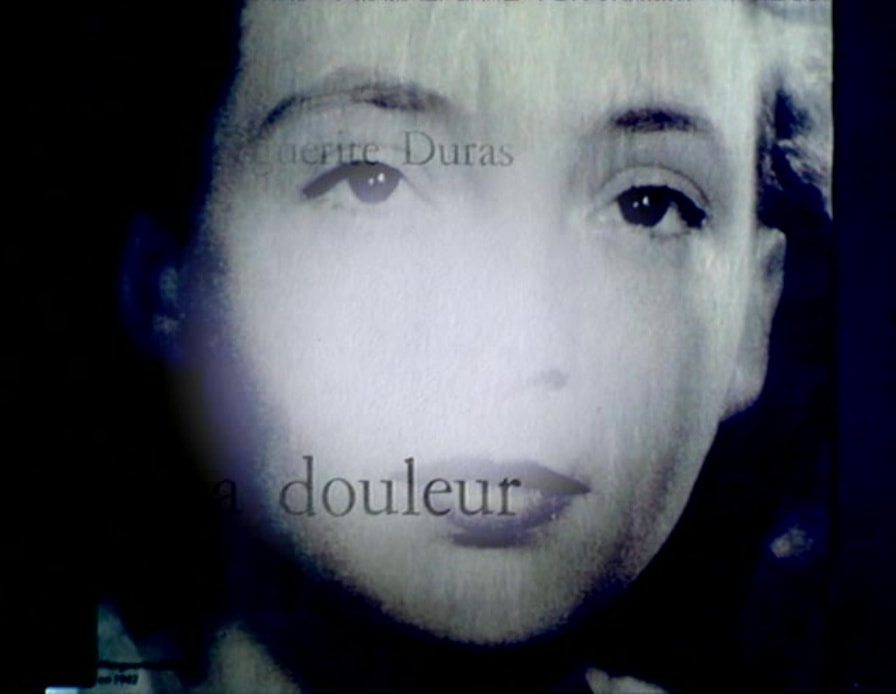

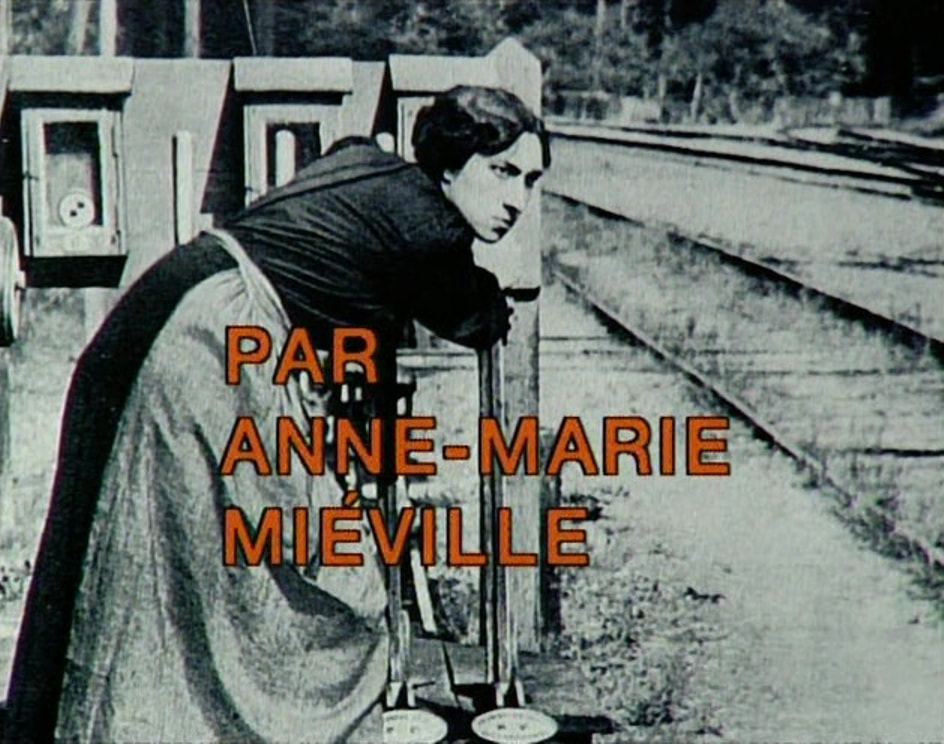

If, in this respect, Godard is no more culpable than those historians from whom he would have first learnt film history (Mitry, Sadoul, Ford and Jeanne, Brasillach and Bardèche), it is a fact that women filmmakers are rarely referenced in Histoire(s) du cinéma, and then mostly only passingly. Anne-Marie Miéville is a constant presence - her name, her voice, her photograph, and images from her films - as is Marguerite Duras:

As is made very clear in Pamela Green's new documentary Be Natural: the Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché, her effacement from cinema history is a long-standing and ongoing wrong that is only now being redressed.

If, in this respect, Godard is no more culpable than those historians from whom he would have first learnt film history (Mitry, Sadoul, Ford and Jeanne, Brasillach and Bardèche), it is a fact that women filmmakers are rarely referenced in Histoire(s) du cinéma, and then mostly only passingly. Anne-Marie Miéville is a constant presence - her name, her voice, her photograph, and images from her films - as is Marguerite Duras:

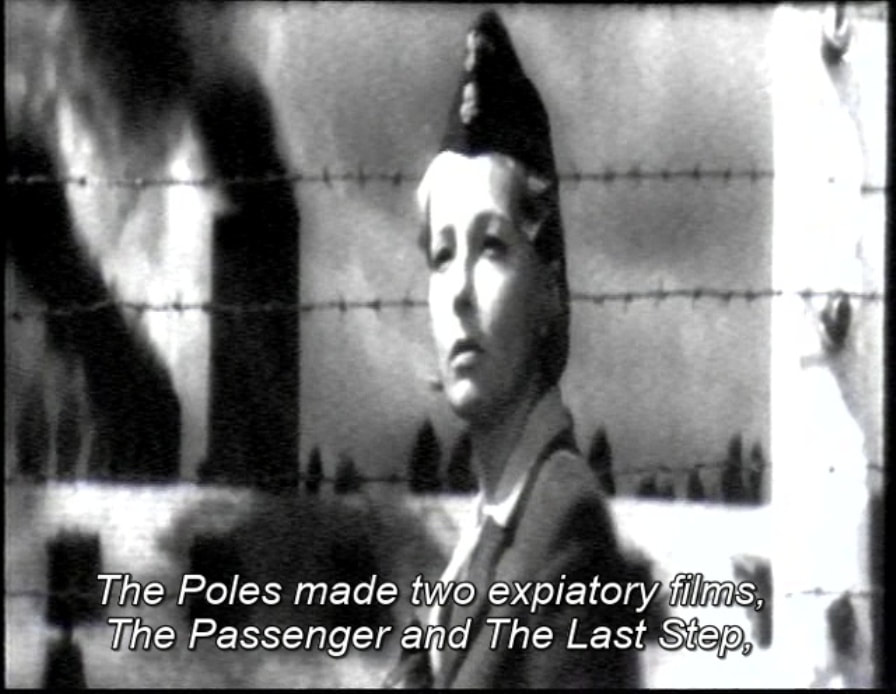

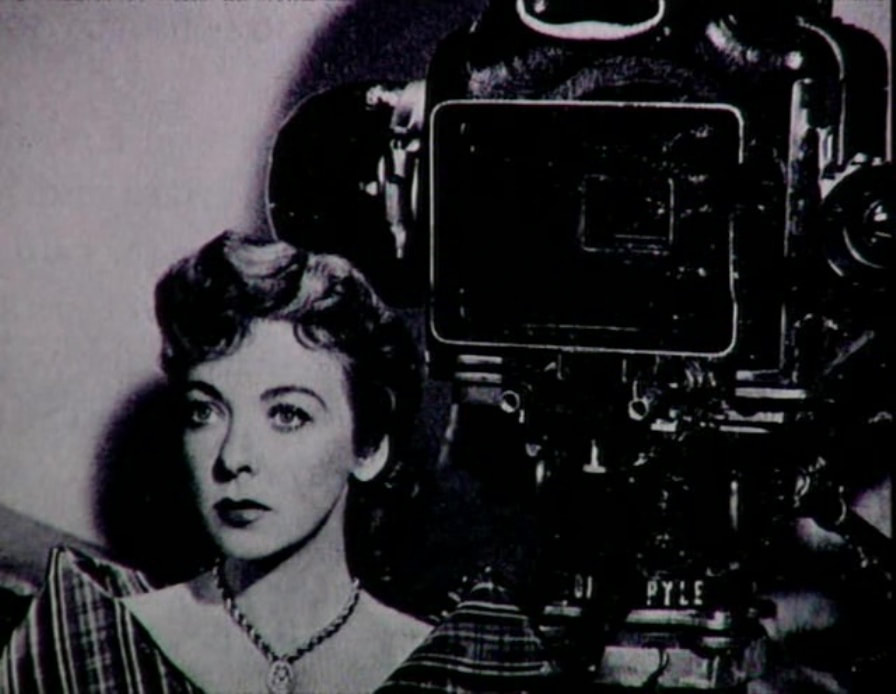

But otherwise the full list is, I think, this: Ida Lupino (a photograph of her directing in 1A and a still from her film Outrage in 2A); Esfir Shub (footage from The Fall of the Romanovs in 1A); Dorothy Davenport (a still from Human Wreckage in 2B); Barbara Loden (a still from Wanda in 2B); Wanda Jakubowska (a mention of The Last Step in 3A); Agnès Varda (a shot from Les Demoiselles ont eu 25 ans in 3B):

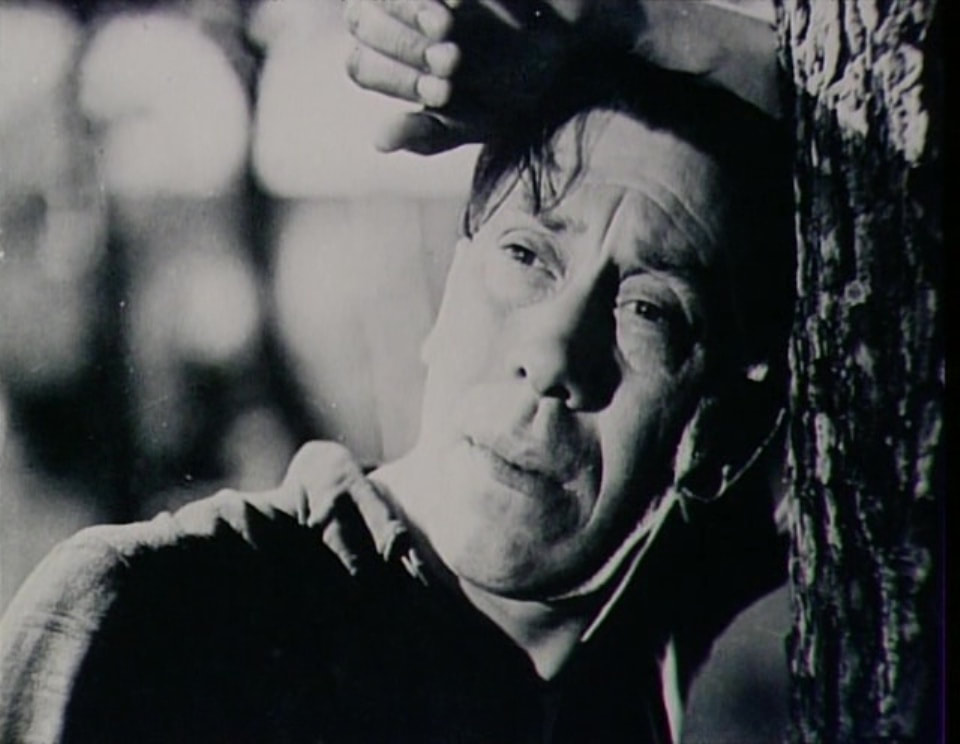

Into the shot from Varda's film is inserted a three-second extract from a film by Alice Guy, the only trace of her existence in Histoire(s) du cinéma:

The film is Sur la barricade (1907), a melodrama depicting an incident from the suppression of the Commune in May 1871.

This whole passage in Histoire(s) du cinéma evokes six now-deceased male filmmakers who had been friends of Godard - Jacques Becker, Roberto Rossellini, Jean-Pierre Melville, Georges Franju, Jacques Demy and François Truffaut - and shows images of each:

This whole passage in Histoire(s) du cinéma evokes six now-deceased male filmmakers who had been friends of Godard - Jacques Becker, Roberto Rossellini, Jean-Pierre Melville, Georges Franju, Jacques Demy and François Truffaut - and shows images of each:

Over some of these images appear the last words of a phrase from Georges Bataille (writing about Jean Genet) that had appeared as screentext three minutes before:

It is difficult to work out what the extract from Sur la barricade is doing at this juncture of Histoire(s) du cinéma. Guy's scene depicts violence between men, contrasting with the theme of friendship between them. That it is an image made by a woman may be of consequence, but perhaps not to the same extent as the fact that the image depicting Godard's friend Jacques Demy was made by a woman. That image with Demy also includes a woman, Catherine Deneuve, and the title of Varda's film, 'the demoiselles are twenty-five years old', implicates women in this section's pathos-laden narrative of loss - the other demoiselle from Demy's 1967 film, Deneuve's sister Françoise Dorléac, died shortly after the footage used by Varda was shot. The superimposed photograph of Truffaut laughing is the counterpart of his grief at the death of Dorléac, his friend and former lover.

This obliquely represented couple has its parallel in the oblique representation of the Varda-Demy couple. The male-female couple is one of the dominant motifs of Histoire(s) du cinéma, especially where man and woman have been brought together by the cinema, as was the case for Truffaut and Dorléac and Demy and Varda. The couple motif is restated immediately after this sequence, with firstly a still of Michel Simon and Missia in Derrière la façade (Georges Lacombe 1939) and then a composed couple of Dita Parlo from Renoir's La Grande Illusion (1937) and Sacha Guitry from his own film Désiré (1937):

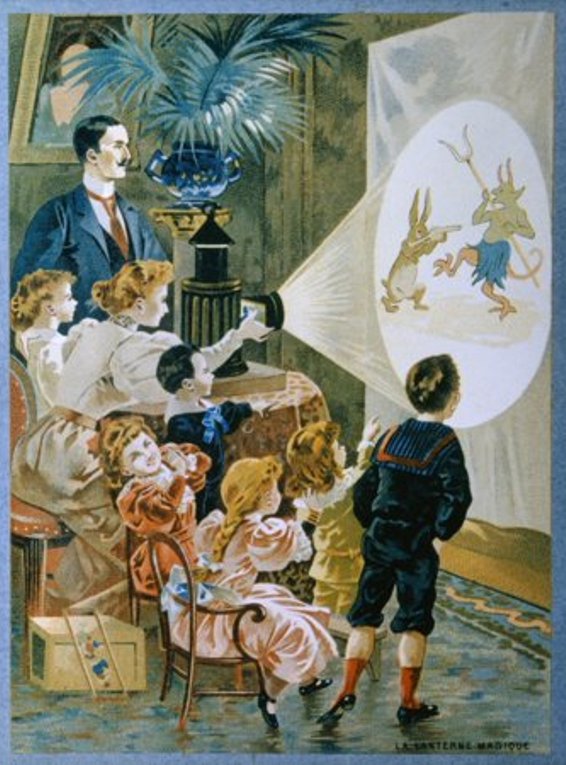

Just prior to the appearance of these comes an image related to a 'woman-operating-apparatus' motif, initiated by Ida Lupino in 1A and recurrent throughout Histoire(s) du cinéma:

The superimposition suggests that the woman operating the magic lantern has produced or is manipulating the image on the wall. The association of this image with the Gaumont production credit is not a coincidence. On five of the seven occasions where the Gaumont credit is placed over an image, that image is of a woman, beginning with Ida Lupino in 1A:

The shot of Ida Lupino from While the City Sleeps (Fritz Lang 1956) shows her examining a slide in a portable viewer, which aligns her with the woman operating the magic lantern at the end of 3B. The witch from Snow White (1B) is preparing the poisonous apple, which first appears as a livid skull before taking the ripe red form by which Snow White will be tempted. The still of a woman (2A) who has turned to see a man watching her - she is stalked and raped by him - is from Ida Lupino's Outrage (1950), and the woman in the drawing (3A) is the novelist George Sand. These are all images associating women with production in general, and specifically with the production company Gaumont.

The intensity of Ida Lupino's gaze is supplemented by apparatus. This opening sequence of Histoire(s) du cinéma has already shown Lupino with a film camera, and goes on to show a portrait of Lupino from when she was only an actress and not a filmmaker, when she was the object rather than the subject of a gaze:

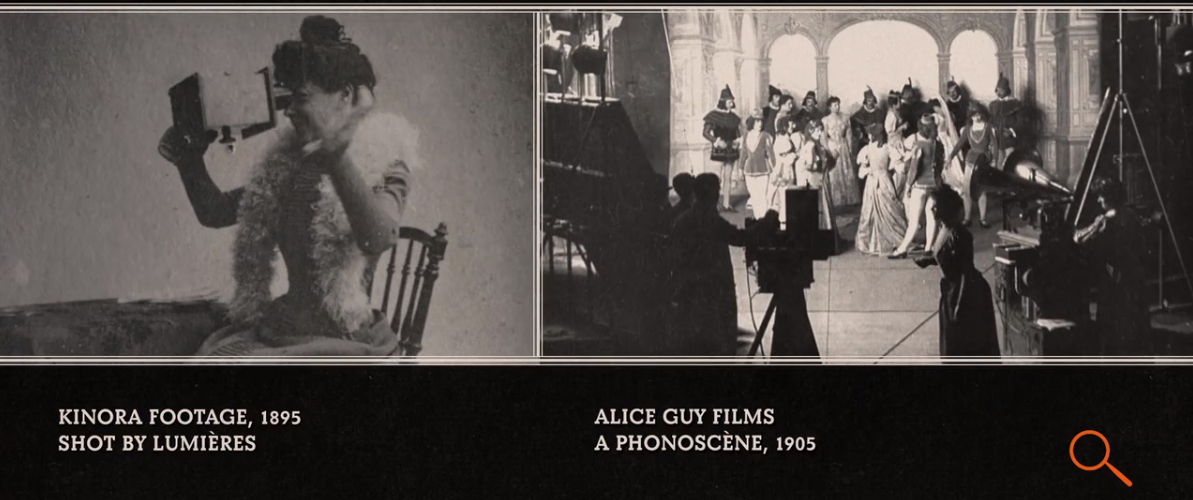

Images of Ida Lupino carry much of the narrative of women as image-producers in Histoire(s) du cinéma, such as it is. A subtext of this post is my regret that this burden isn't shared with Alice Guy. It is true that the Gaumont box set featuring sixty-five of her French films from between 1898 and 1907 didn't appear until 2008, ten years after the completion of Histoire(s) du cinéma, and of course nor was the wealth of further material accumulated by Pamela Green for Be Natural in 2018 available to Godard. It seems to me that, for example, the images made for a Lumière Kinora of Guy looking into a Lumière Kinora, or the film showing Guy directing a phonoscene, surrounded by image- and sound-recording apparatus, belong in the Histoire(s) du cinéma:

In the absence of Alice Guy, Ida Lupino alone ties the motif of women with apparatus to the idea of women as image-producers. If Godard used the extract from Sur la barricade because it was an image produced by a woman, it is just possible that the image of the woman deploying a magic lantern that appears nine seconds after the extract, with the words Production Gaumont above her head, is supposed to represent Alice Guy:

Very likely this is wishful thinking on my part, though not as wishful as the thought that Godard could have placed here this image, if he had had it to hand:

2/ Deux fois 50 ans de cinéma français (1995)

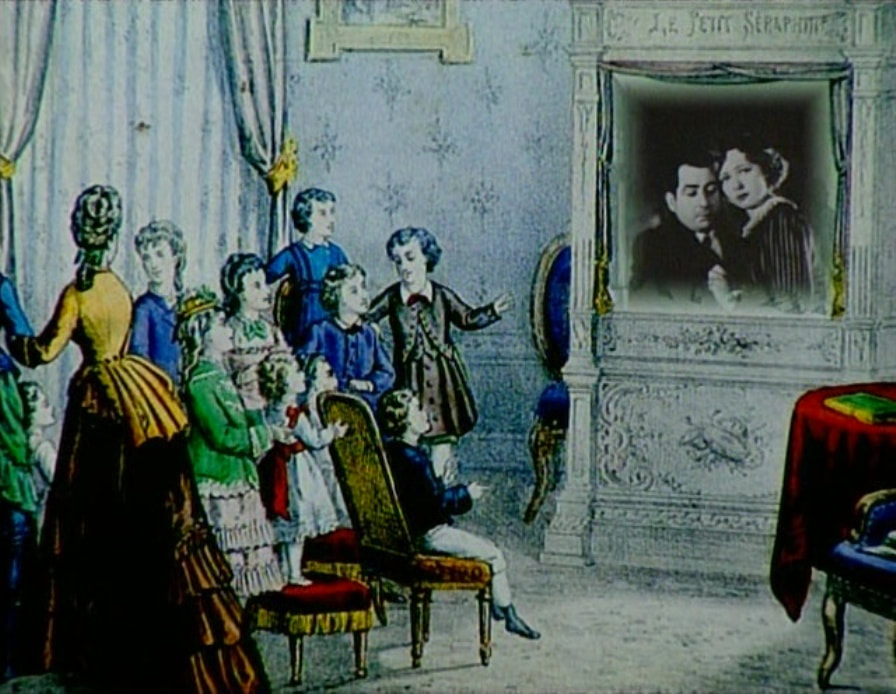

While he was working on the latter parts of Histoire(s) du cinéma, Godard made with Anne-Marie Miéville an essay-film on the history of French cinema, commissioned by the BFI to commemorate cinema's centenary. A minute or so from the beginning of this film appears the image of a woman operating a magic lantern, this time unencumbered by superimpositions:

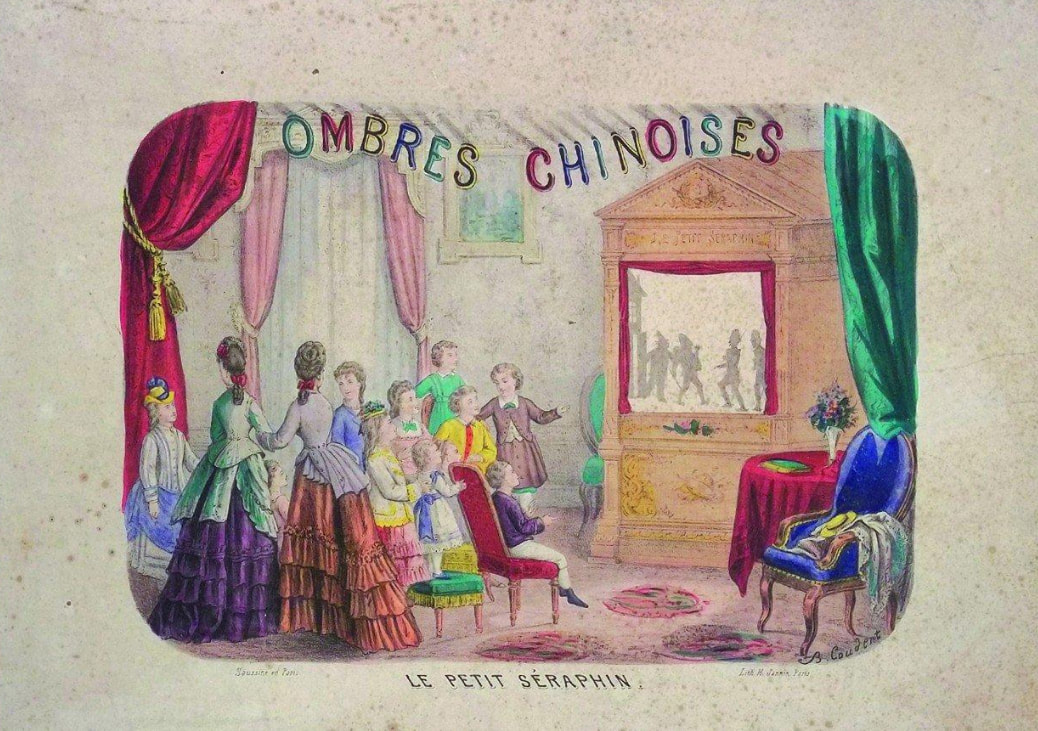

At more or less the same distance from the end of the film a complementary image shows a family in front of a 'Chinese shadows' theatre - with Carette and Dubost from Renoir's La Règle du jeu (1939) as the show:

Both of these images of pre-cinematic media are French and from around 1880. Both have been cropped before insertion into 2 x 50 ans:

The cropping of the Chinese shadow image can make it seem like the woman to the left is operating a projector, strengthening the connection with the magic lantern image.

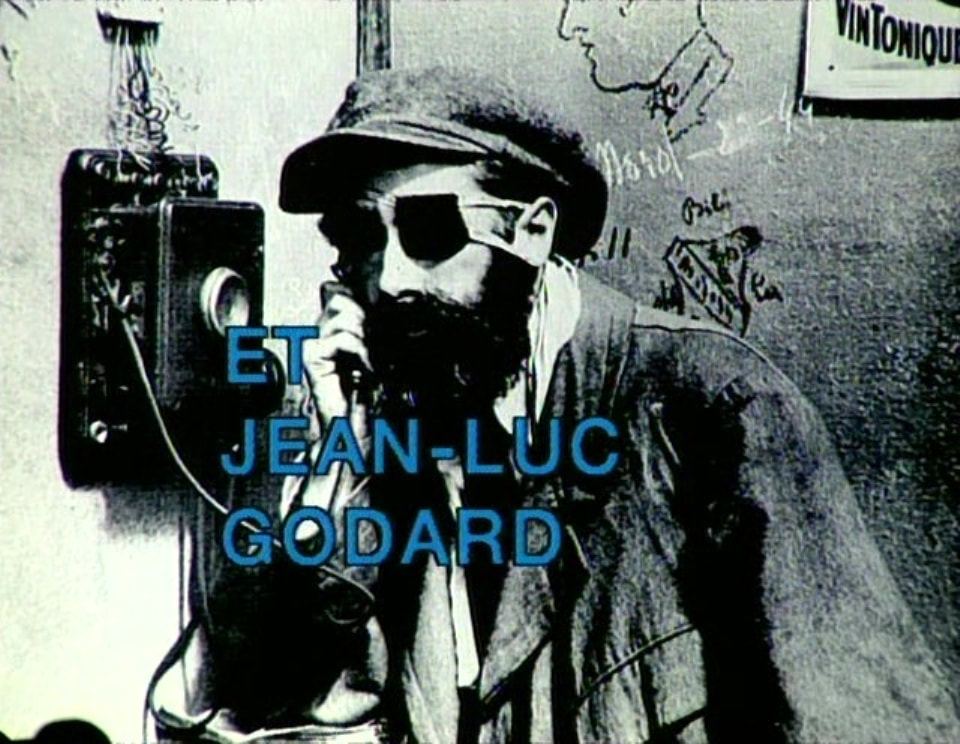

If I can imagine that the magic lantern image in Histoire(s) du cinéma, with its 'Production Gaumont' inscription, might be hinting at the presence of Alice Guy, I suppose I could suggest that she is similarly present in Deux fois 50 ans, even if the Gaumont company is not one of the latter's producers. It is above all early Gaumont films that Miéville and Godard use to represent the early years of French cinema. Their names in the credits are presented over stills from films by Léonce Perret (Sur la voie 1914) and Louis Feuillade (Judex 1916):

If I can imagine that the magic lantern image in Histoire(s) du cinéma, with its 'Production Gaumont' inscription, might be hinting at the presence of Alice Guy, I suppose I could suggest that she is similarly present in Deux fois 50 ans, even if the Gaumont company is not one of the latter's producers. It is above all early Gaumont films that Miéville and Godard use to represent the early years of French cinema. Their names in the credits are presented over stills from films by Léonce Perret (Sur la voie 1914) and Louis Feuillade (Judex 1916):

Twelves minute in, a passage on the forgetting of once famous names from cinema, and on how 'old' films are viewed now, is accompanied by two extracts from films by Feuillade (Une dame vraiment bien 1908; Juve contre Fantômas 1913) and one from a film by Alice Guy, Sur la barricade again:

The two Feuillade films show interactions between men and women, with the women constituted as spectacle, and it could be that the film made by a woman is then shown to serve as counter-weight.

When Deux fois 50 ans shows Guy's recollection of the Commune - a politically charged act in 1907 - Godard is speaking of commemoration, giving the fiftieth or hundredth anniversary of the death camps as example and pointing out that Resnais's Nuit et Brouillard would not forasmuch be shown every night on TV with the injunction not to forget:

When Deux fois 50 ans shows Guy's recollection of the Commune - a politically charged act in 1907 - Godard is speaking of commemoration, giving the fiftieth or hundredth anniversary of the death camps as example and pointing out that Resnais's Nuit et Brouillard would not forasmuch be shown every night on TV with the injunction not to forget:

In Une femme mariée (1964), Godard had imagined the equivalent of this suggestion when he has the lovers meet in the cinema at Orly airport, and the film they are watching is Nuit et Brouillard.

Institutional commemoration, be it of the Holocaust or the Invention of Cinema, is Godard's subject at this juncture of Deux fois 50 ans, and though the evocation of the Commune could be making a point about counter-institutional commemoration, it is also, more simply, a remembering of Alice Guy's film.

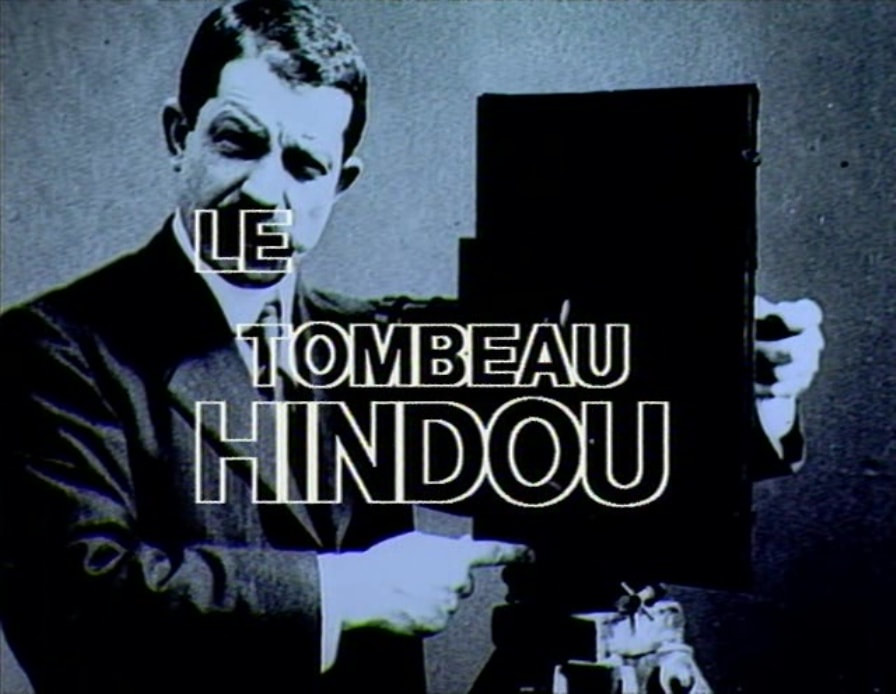

He continues with a discussion of the relation between the camera and the projector, showing firstly a picture of the Pathé brothers holding a phonograph and a projector, then the footage of Léon Gaumont demonstrating his camera:

Institutional commemoration, be it of the Holocaust or the Invention of Cinema, is Godard's subject at this juncture of Deux fois 50 ans, and though the evocation of the Commune could be making a point about counter-institutional commemoration, it is also, more simply, a remembering of Alice Guy's film.

He continues with a discussion of the relation between the camera and the projector, showing firstly a picture of the Pathé brothers holding a phonograph and a projector, then the footage of Léon Gaumont demonstrating his camera:

Godard then moves to a contrast between Lumière and Edison, the French inventor and the American copyist. To illustrate this opposition the Arrivée d'un train of 1896 dissolves into W.S. Van Dyke's San Francisco (1936), as if Jeanette MacDonald was an American-made avatar of the woman who had got off the Lumière train:

Godard is remembering these two films, and also suggesting that the one has remembered the other. I can't help imagining that this is also a memory of Alice Guy, who moved from making films for Gaumont in France to making films for herself in the U.S.A., at almost exactly the time represented in the American film - San Francisco is set at the time of the 1906 earthquake, Guy moved to the U.S. in 1907. (A little later in Deux fois 50 ans Godard evokes a French filmmaker who in 1916 went to make films in the U.S.: the Pathé star Max Linder.)

The soundtrack accompanying the dissolve from France to the USA is the waltz from La Ronde by Max Ophuls, a filmmaker who in 1950 had just made the journey in the opposite direction, moving from Hollywood to Paris. La Ronde is set in 1900, almost exactly between the moments of the two women on screen.

As the lyrics of the waltz suggest analogies with cinema - 'the waltz turns ... the carrousel turns .. my characters turn...' - the voice of Godard returns to say to Michel Piccoli, President of the Association to Commemorate the First Century of Cinema: 'Well, if you project Alice Guy's films on TF1, that will be interesting...'. At no other time, I think, does Godard refer to Guy by name - not in any of his films, nor in any published texts or interviews. Her image, as opposed to an image from one of her films, appears only once, about halfway through Deux fois 50 ans, between a photograph of Feuillade and a photograph of Duras:

As the lyrics of the waltz suggest analogies with cinema - 'the waltz turns ... the carrousel turns .. my characters turn...' - the voice of Godard returns to say to Michel Piccoli, President of the Association to Commemorate the First Century of Cinema: 'Well, if you project Alice Guy's films on TF1, that will be interesting...'. At no other time, I think, does Godard refer to Guy by name - not in any of his films, nor in any published texts or interviews. Her image, as opposed to an image from one of her films, appears only once, about halfway through Deux fois 50 ans, between a photograph of Feuillade and a photograph of Duras:

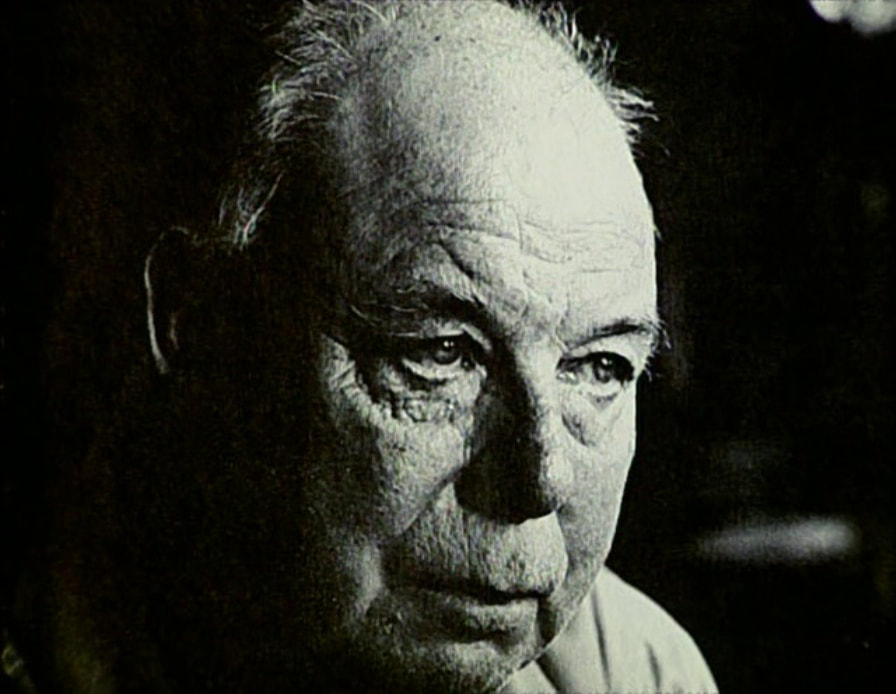

Guy appears here in a sequence of portraits of French cinema personalities, beginning with two comic actors, Marcel Lévesque and Fernandel, followed by two directors with whom these two were closely associated, Pagnol and Feuillade. Then come Guy and Duras as a pairing, their photographs linked by a slow dissolve from one to the other. After that come twelve men: Robert Bresson, Jean Epstein (I think), Max Ophuls, Jacques Becker, Abel Gance, Jacques Tati, Jean Renoir, Jacques Prévert and Marcel Carné (their photographs superimposed), André Malraux, Jean-Pierre Melville and Roger Leenhardt, the latter not a photograph but a shot of him speaking in Une femme mariée - Leenhardt's discourse on intelligence is heard throughout this succession of images. Between most of the images appears a title reading NO COPY RIGHT, which I think is meant simply to affirm the originality of French cinema:

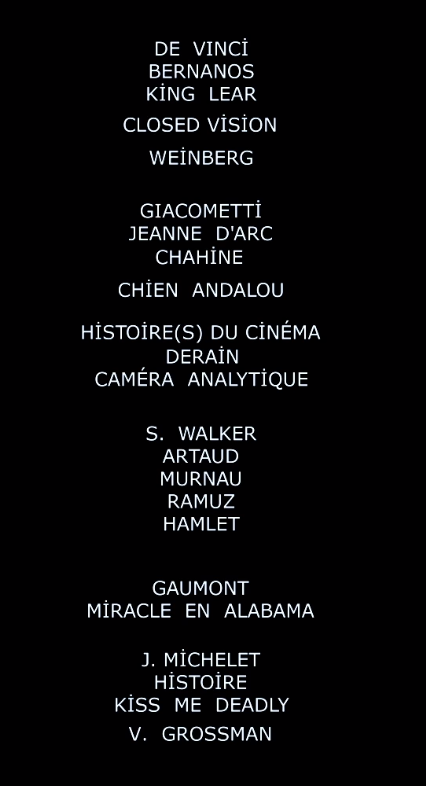

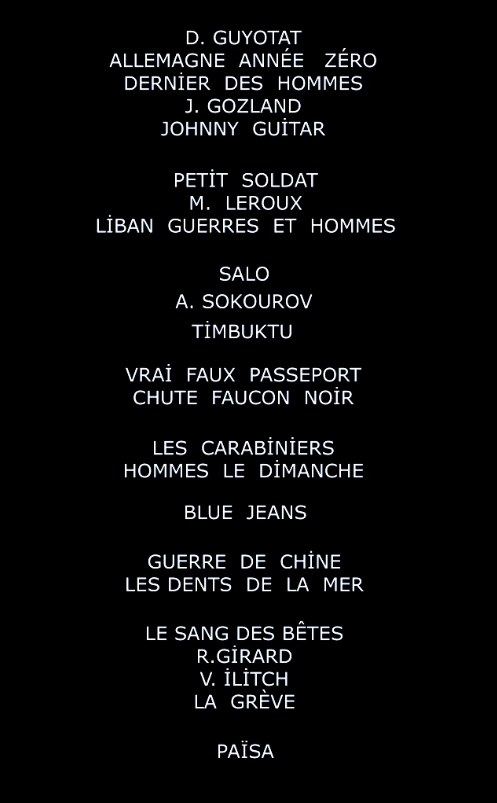

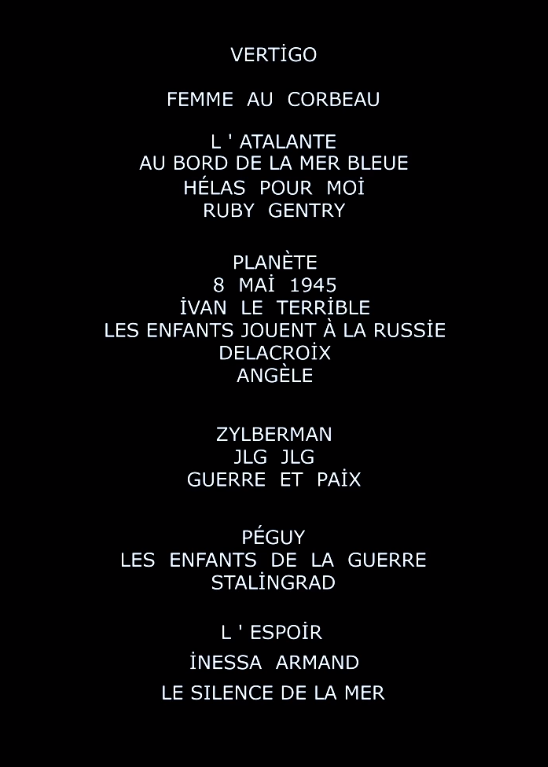

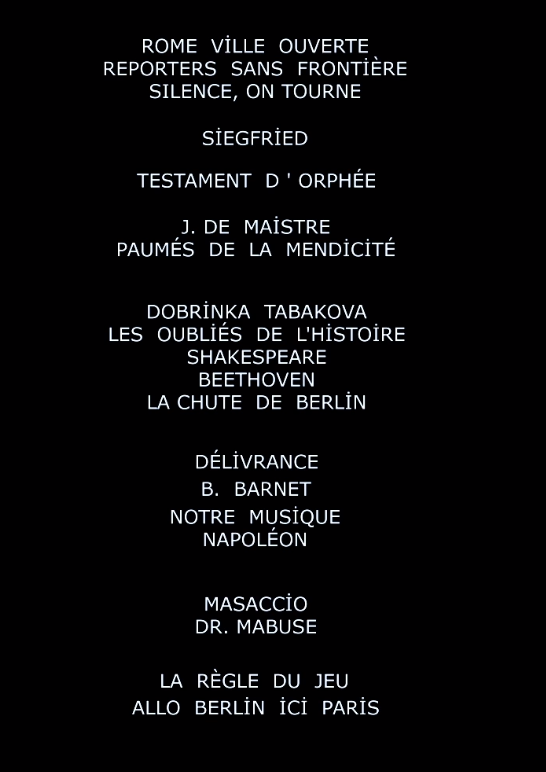

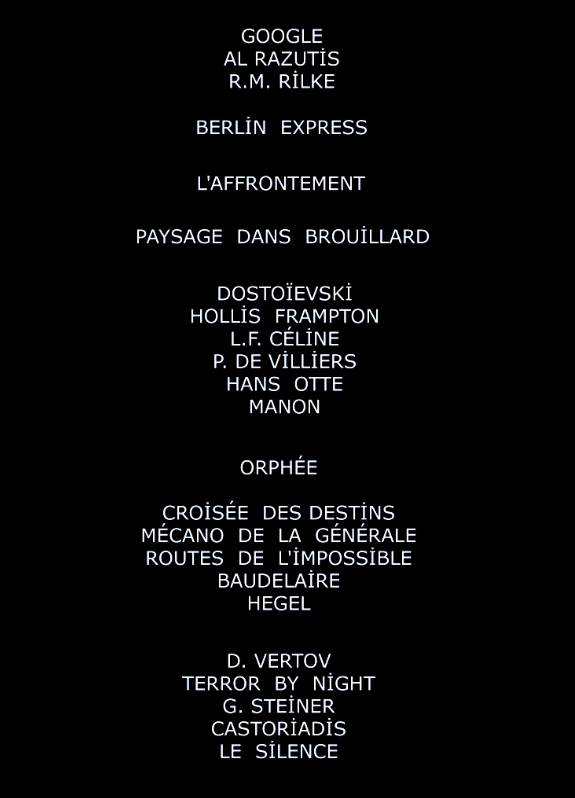

The placing here of two women filmmakers is a corrective to the litanies of male directors that Godard presents in Histoire(s) du cinéma, be it the list of departed friends in episode 3B - Jacques Becker, Roberto Rossellini, Georges Franju, Jean-Pierre Melville, François Truffaut and Jacques Demy:

Or the panoply of film artists in episode 4A - Robert Bresson, Fritz Lang, Jean Cocteau, Eric Rohmer, François Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, Luchino Visconti, Philippe Garrel and Rainer Werner Fassbinder:

The superimposition of Guy and Duras in Deux fois 50 ans suggests a certain solidarity faced with the preponderance of men in Godard's pantheons:

But this doesn't mean that the history of French cinema told in Deux fois 50 ans gives their due place to women filmmakers. Duras does return at the end as the one woman among fifteen thinkers of the visual:

And earlier, discussing this critical tradition as something unique to French cinema, Godard mentions Germaine Dulac alongside Louis Delluc and Jean-Georges Auriol.

And that's it: Alice Guy, Germaine Dulac, Marguerite Duras and Anne-Marie Miéville are the only women filmmakers featured in Miéville and Godard's account of French film history.

In a postface I wrote this year to Suzanne Liandrat-Guigues essay on Nicole Vedrès's film Paris 1900 (regarding which see here), I expressed surprise that nowhere in Deux fois 50 ans is Vedrès mentioned, when her work as an archival filmmaker is clearly an important precedent for archival filmmakers like Marker and Godard. Marker acknowledged fully his debt to Vedrès; Godard has never mentioned her.

And that's it: Alice Guy, Germaine Dulac, Marguerite Duras and Anne-Marie Miéville are the only women filmmakers featured in Miéville and Godard's account of French film history.

In a postface I wrote this year to Suzanne Liandrat-Guigues essay on Nicole Vedrès's film Paris 1900 (regarding which see here), I expressed surprise that nowhere in Deux fois 50 ans is Vedrès mentioned, when her work as an archival filmmaker is clearly an important precedent for archival filmmakers like Marker and Godard. Marker acknowledged fully his debt to Vedrès; Godard has never mentioned her.

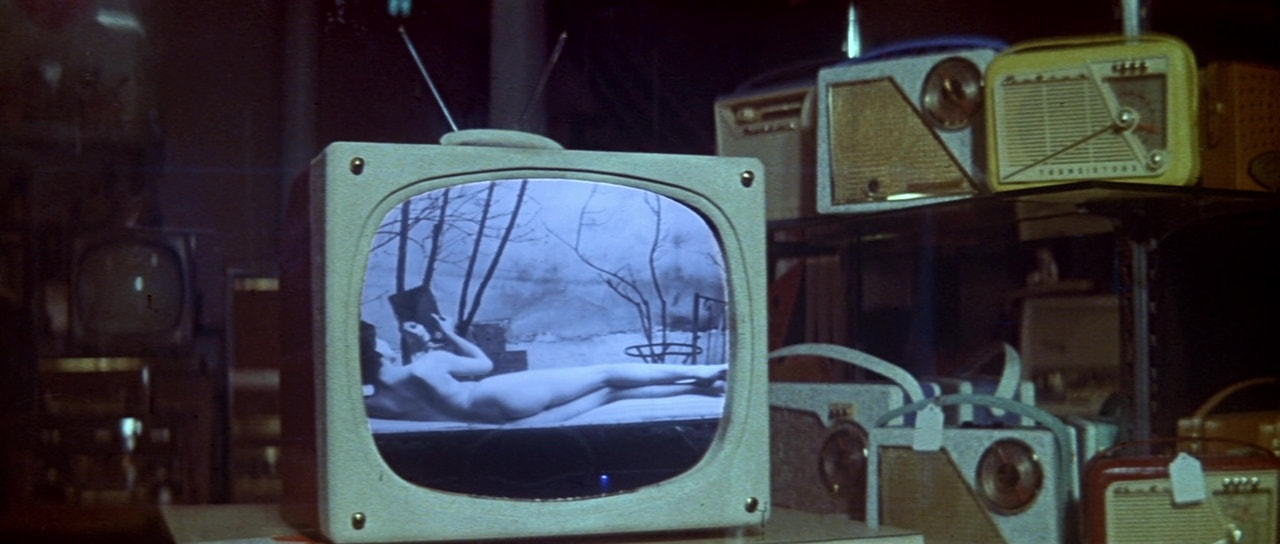

As cine-referential as Godard's work is more generally, going back to his very first films, it is difficult to think of many instances where a film of his has referenced a film by a woman. In Une femme est une femme (1961) we see passages from Varda's L'Opéra Mouffe (1958) on a television in a shop:

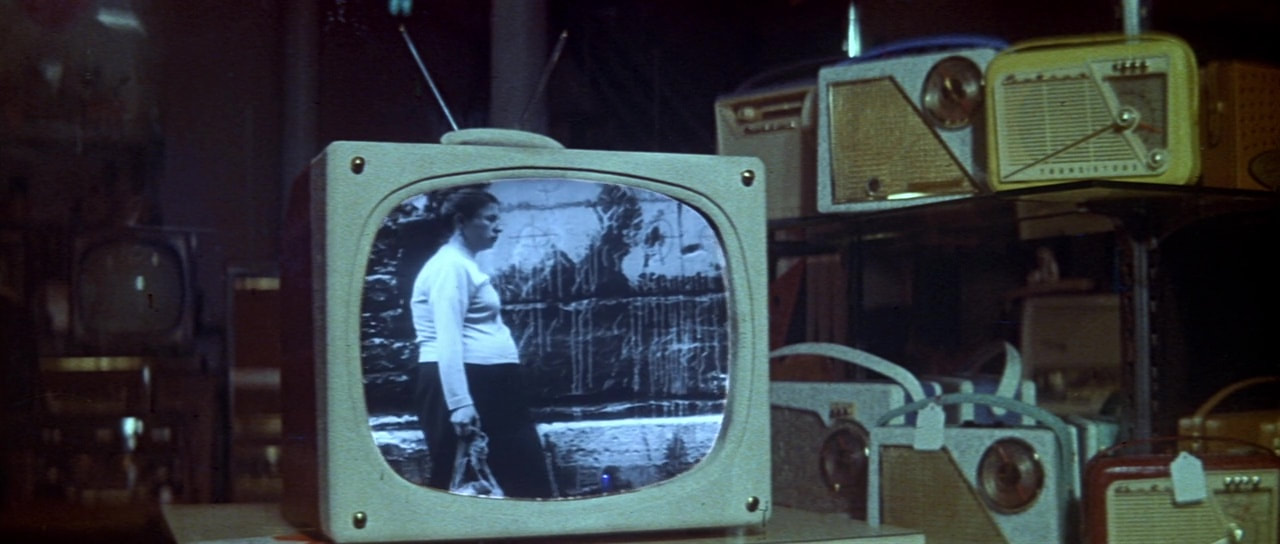

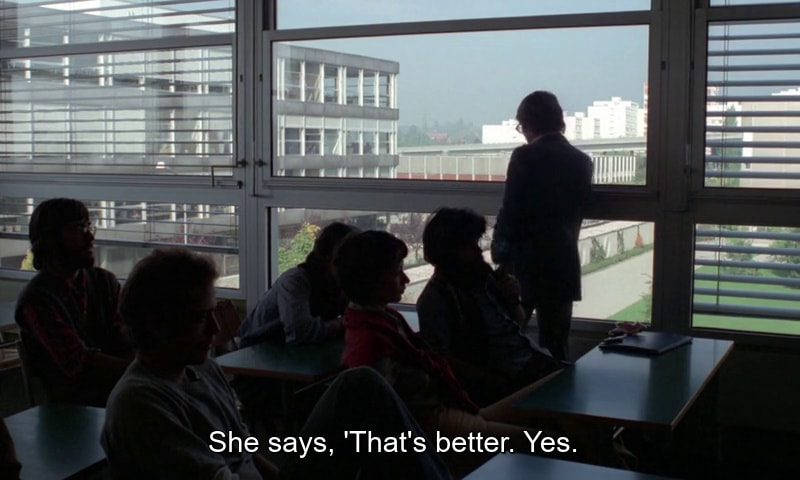

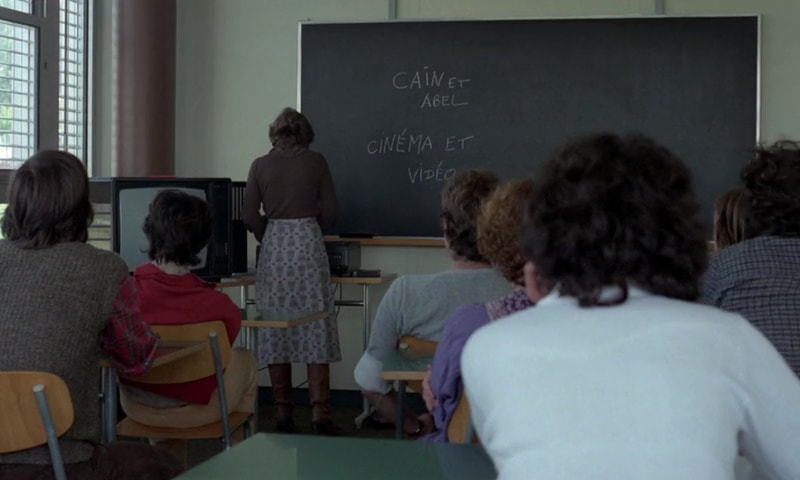

In Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1980) students watch a video-cassette of Duras's Le Camion (1977). We don't see the image but we hear the sound:

According to the IMDB there is poster for Barbra Streisand's The Prince of Tides (1991) in Hélas pour moi (1993), but I haven't been able to spot it yet. I have seen the poster for Samira Makhmalbaf's La Pomme (1998) in Eloge de l'amour (2001):

And I think that is it.

(If I've missed any other references to films by women in Godard's films, please do let me know.)

3/ Notre musique (2006) - Royaume 1: Enfer

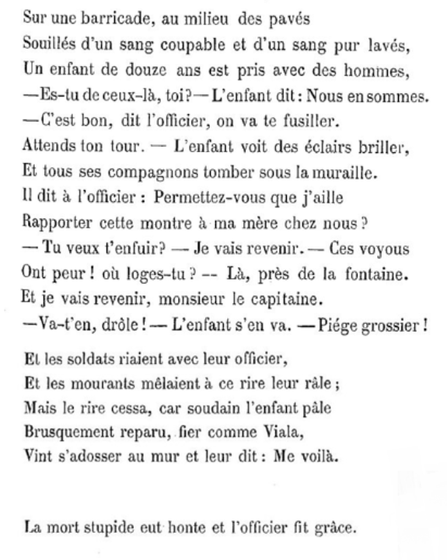

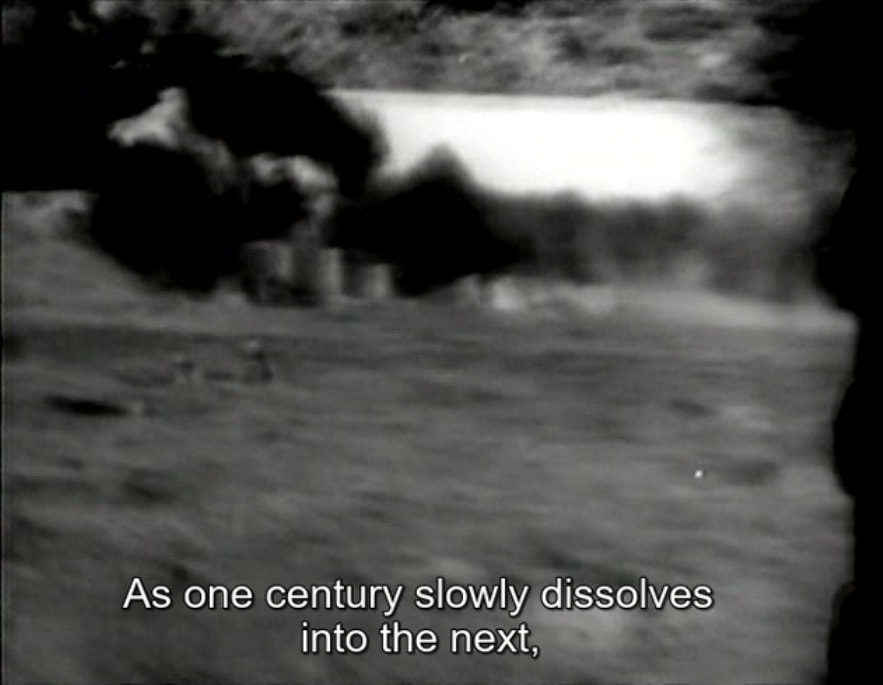

The first section of Notre musique, headed 'Hell', is a nine-minute montage of film and television images related to war. Some of those images are related by analogy, such as the shot of nuns from Robert Bresson's Les Anges du péché (1943), but most are direct representations of combat and death. The now-familiar shot from Guy's Sur la barricade occurs between views of tanks and explosions:

4/ Le Livre d'image (2018)

Of the other collagist films made by Godard or Godard and Miéville, I would find it difficult to be sure I hadn't missed something if I tried to enumerate the references to women filmmakers. Some of those films come with credits that list the films cited, so we know for example that Film Socialisme references Varda's Les Plages d'Agnès (2008), Karin Albou's Le Chant des mariées (2008) and Florence Mauro's Simone Weil, l'irrégulière (2009).

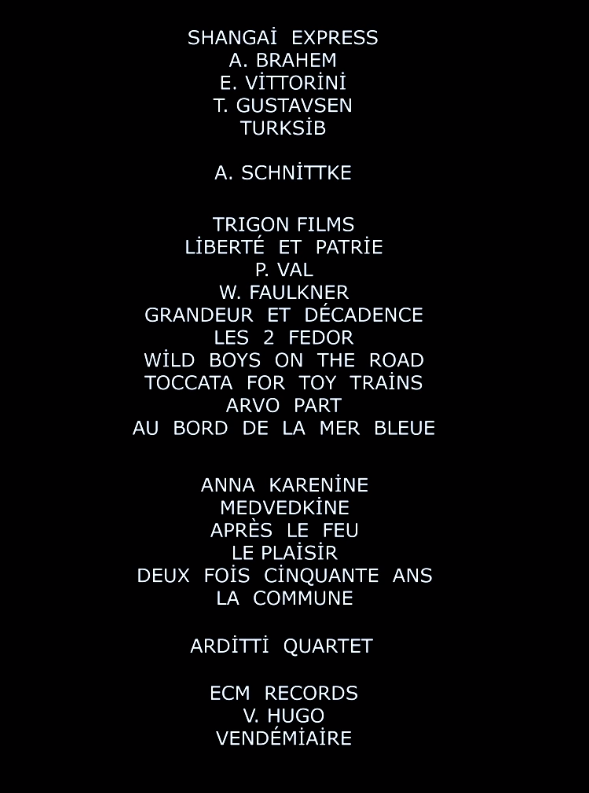

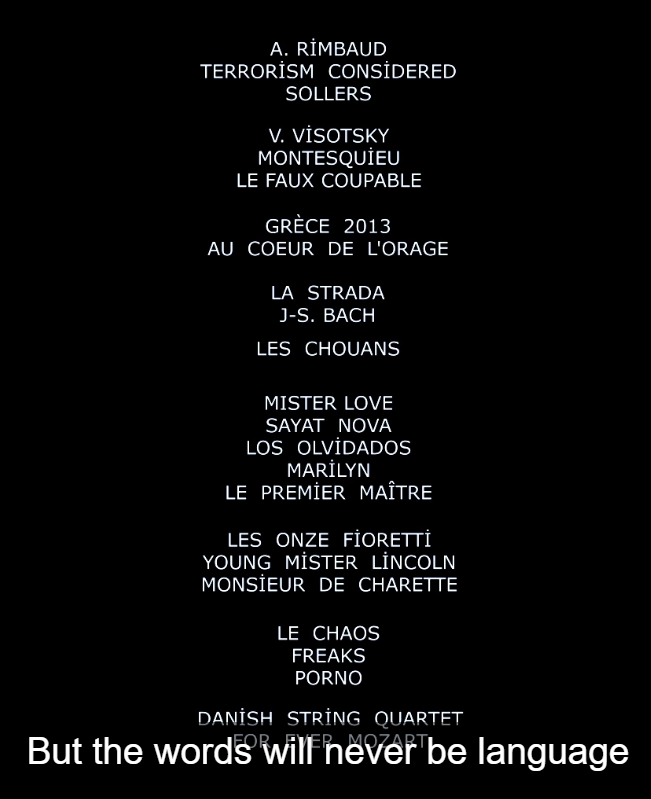

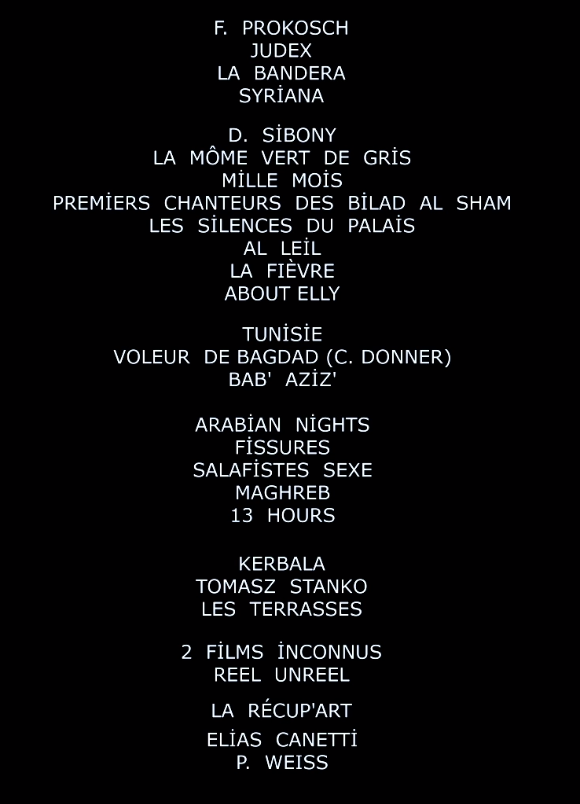

The eleven pages of credits at the end of Le Livre d'image mix together all of the references - texts, music, paintings, photographs, films, etc. -, listing these in the order in which they appear in the film. The references are minimal so it isn't always possible to tell what kind of object is being referred to:

From what I can work out, only three films by women are credited in Le Livre d'image: Tamaout by Dominique Isserman and Marc'O (1970), Les Silences du palais by Moufida Tlatli (1994) and Maya Deren's Meshes of the Afternoon (1943).

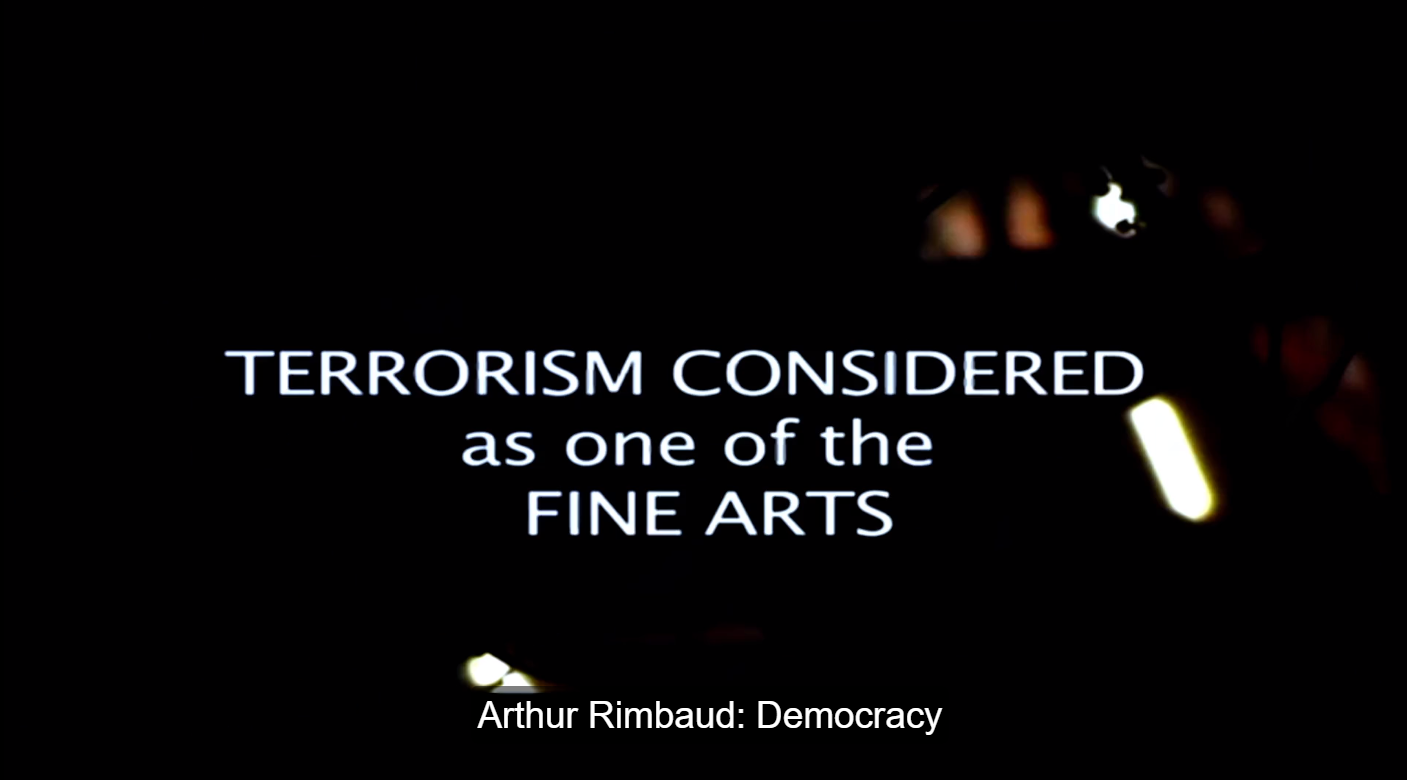

This is curious, because in the fourth section of the film Godard once again uses an extract - the same extract - from Alice Guy's Sur la barricade (1907). In this instance it appears just after an extract from Peter Watkins's La Commune (2000) and before a photograph of Arthur Rimbaud - Rimbaud was in sympathy with and influenced by the Commune, and may well have been in Paris at some point during the period of the Commune, March-May 1871:

Just as he has done with Guy's film, these accompanying visual materials have already been used by Godard. A longer extract from La Commune was used in Vrai faux passeport (2006) in a passage on how film can access the historical real without resorting to documentary. Rimbaud appeared at the end of Histoire(s) du cinéma in combination with footage of De Gaulle, a characteristic montage-as-history-lesson. This montage was accompanied by a history lesson from Rimbaud's Une saison en enfer - 'Men and women used to believe in prophets, now they believe in statesmen':

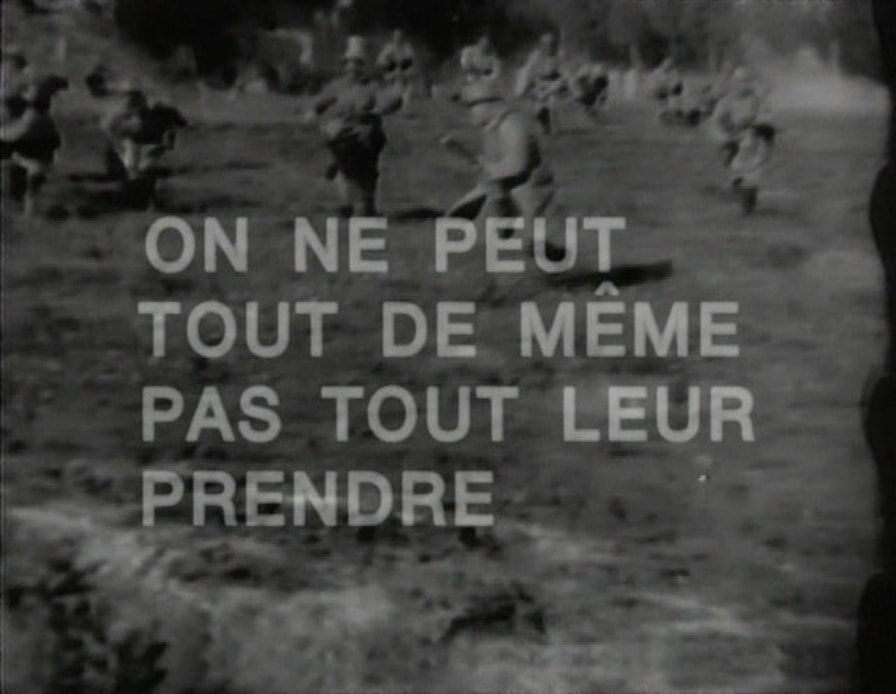

The materials assembled in Le Livre d'image combine to evoke directly the Paris Commune of 1871. This time Sur la barricade is cited by Godard for its specific content, rather than because it showed generic violence, or because it was made by a woman, or made by the Gaumont company. The voice-over text accompanying the shot is taken from Victor Hugo, the opening of a chapter headed 'The horizon viewed from on top of a barricade': 'The general situation, at that fatal hour and in that inexorable place, had as consequence and pinnacle the supreme melancholy of Enjolras.' The heading of this chapter is not given in Le Livre d'image, no barricade is mentioned, as if Godard's film were avoiding an explicit allusion to the name of Guy's film.

The context of the quotation from Hugo does seem to make it, like the reference to Watkins, Guy and Rimbaud, a direct evocation of the historical event, but Hugo's text is from Les Miserables (1862), and is about the barricades of 1848, not those of 1871.

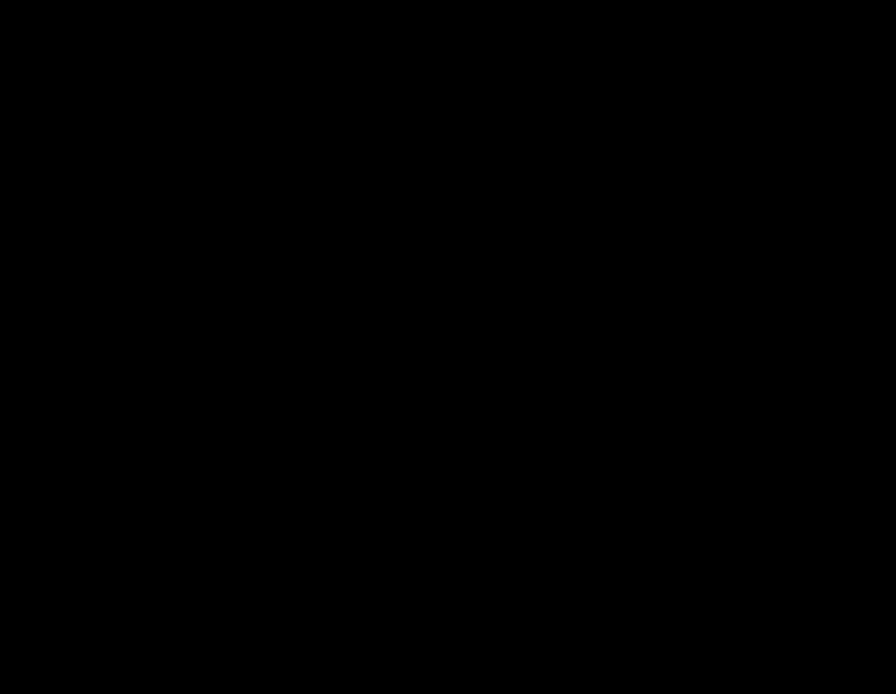

Guy's film, also known as L'Emeute, was itself based on a text by Hugo, the poem 'Sur une barricade...', published in the 1872 collection L'Année terrible and explicitly about the historical moment of the Commune:

The Commune-related passage in Le Livre d'image follows the quotation from Hugo with the opening of Rimbaud's prose poem 'Democracy': 'Le drapeau va au paysage immonde, et notre patois étouffe le tambour' - 'The flag fits the foul landscape, and our patois drowns out the drum' (Joyce O. Lowrie's translation). The text spoken in Godard's film is not quite an exact quotation: where Rimbaud's poem has 'immonde', foul, Godard's text has 'infâme', terrible or abject ('infâme' doesn't mean infamous). The sense difference is slight, but a Godardian cannot help but remember an earlier use of the word 'infâme' by Godard, fifty-seven years earlier, at the end of Une femme est une femme:

|

Angela: Pourquoi tu rigoles?

Emile: Parce que, Angela, tu as infâme. Angela: Moi? Je ne suis pas infâme, je suis une femme. |

Why are you laughing?

Because, Angela, you are terrible. Me? I'm not terrible, I'm a woman. |

To know that Godard can hear 'une femme' in the word 'infâme' might prompt us to look in this passage of Le Livre d'image for any signifying women. Just before the film cuts to Guy's Sur la barricade the extract from La Commune shows several Communard women shouting 'Vive la sociale' and rejoicing at having won over the soldiers sent to repress them:

Alice Guy is also, of course, at this juncture a signifying woman. But here is where I come to my closing point about Godard's referencing of Guy and other women filmmakers. I have mentioned that the copious credits at the end of Le Livre d'image don't include a credit for the extract from Sur la barricade. The credits for the Commune-related passage straddle two pages:

The music heard is firstly a modern string quartet (by Peter Ruzicka possibly?) and then a piece for viola by Hindemith that Godard had already used in Histoire(s) du cinéma. The credits for the Arditti Quartet and ECM records account for those. The extract from La Commune is preceded by footage of film running through a projector that had been used in Deux fois 50 ans. The quotations from Hugo and Rimbaud are credited, and the 'Terrorism Considered' phrase is an abbreviated version of the title of a 2009 film by Peter Whitehead, cited in Le Livre d'images as the Rimbaud quote is completed, along with the name of its production company:

But there where Alice Guy's Sur la barricade should be credited is the word 'Vendémiaire', the title of a 1918 film by Louis Feuillade. One particular shot from Vendémiaire is repeatedly quoted by Godard. I didn't see it in Le Livre d'image but I did see it in the last episode of Histoire(s) du cinéma and in Deux fois 50 ans de cinéma français, not far from where the extract from Sur la barricade appears:

My guess is that Godard, or the person charged with compiling the credits for Le Livre d'image, has simply confused one frequently used extract from a Gaumont film showing men holding guns with another frequently used extract from a Gaumont film showing men holding guns, and that the effacement of a woman filmmaker from those credits was an accident rather than wilfulness.

Nonetheless, the crediting to men of films made by Alice Guy has a long history, and it would have been good for it not to have happened again, in 2018.

Nonetheless, the crediting to men of films made by Alice Guy has a long history, and it would have been good for it not to have happened again, in 2018.