|

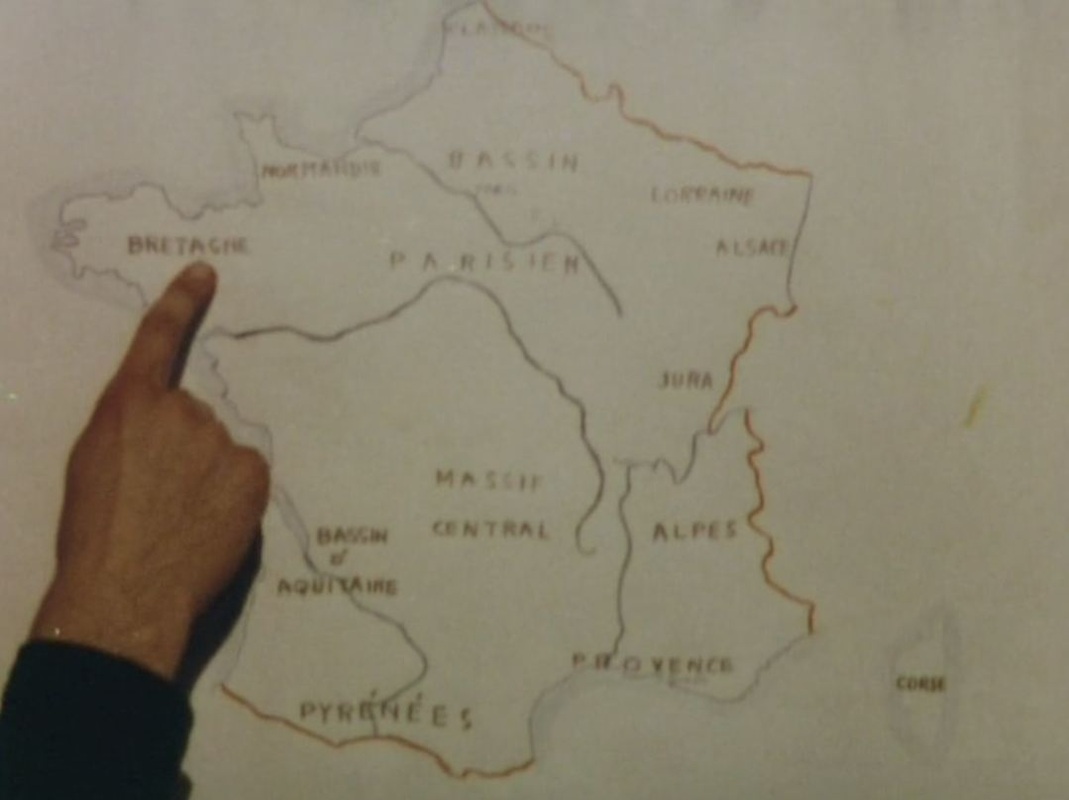

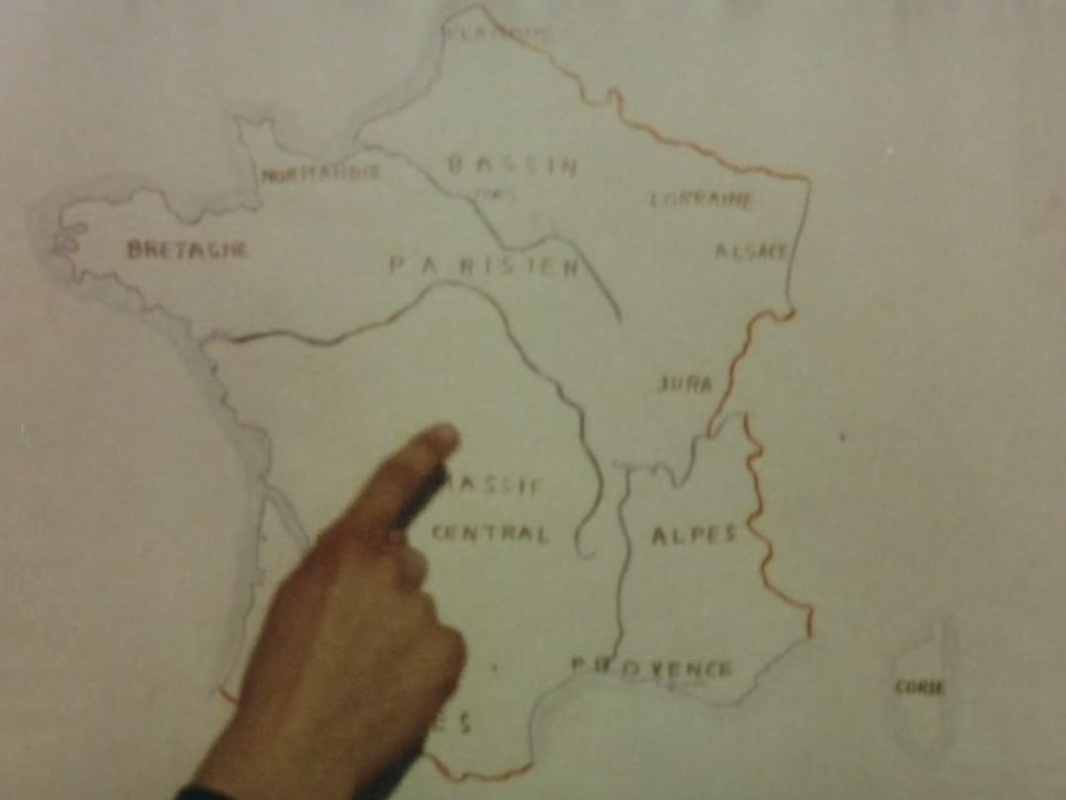

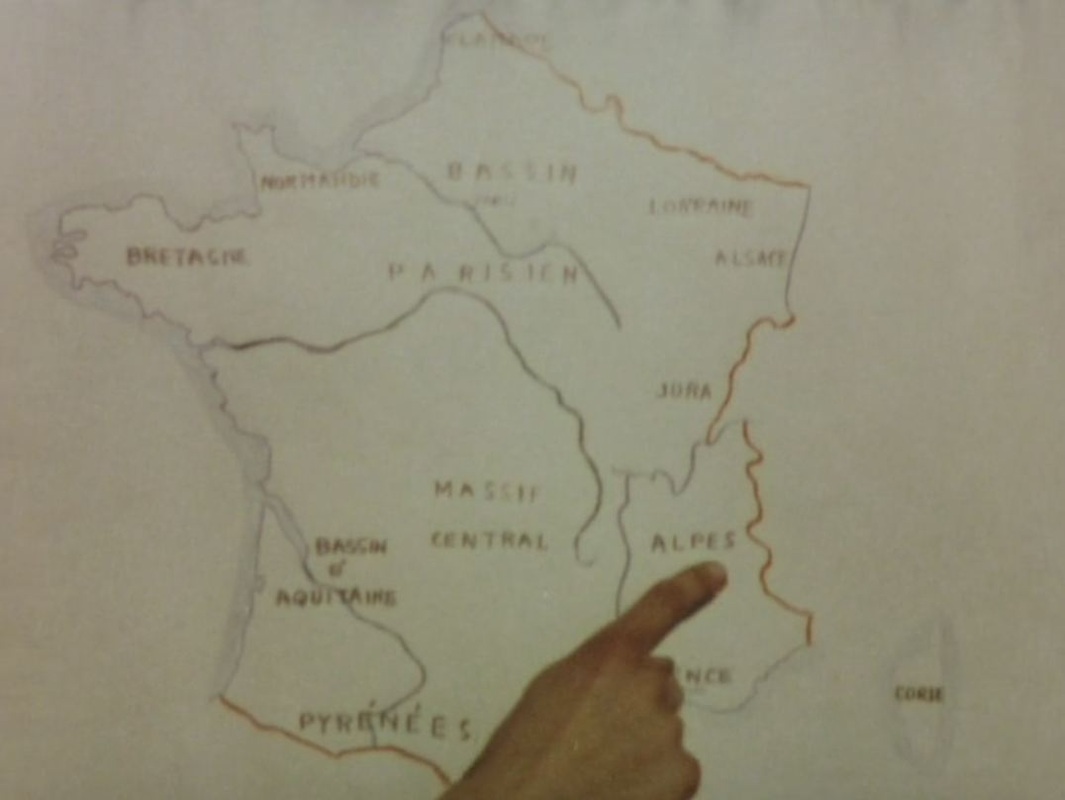

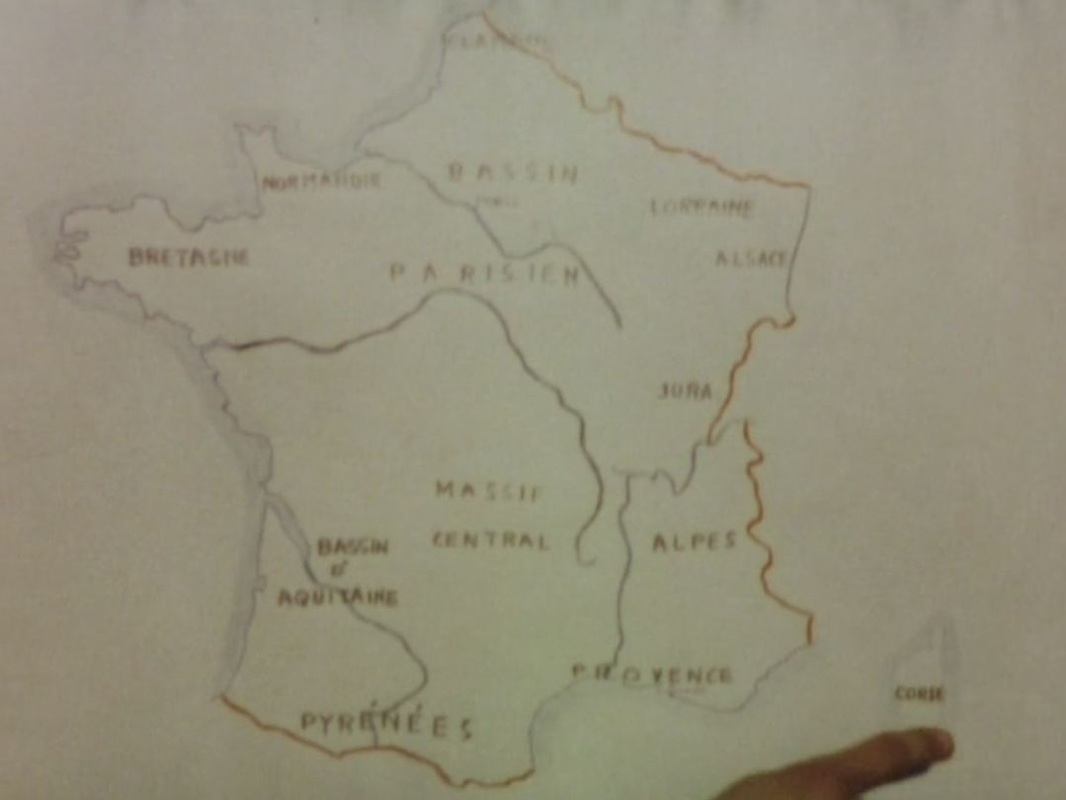

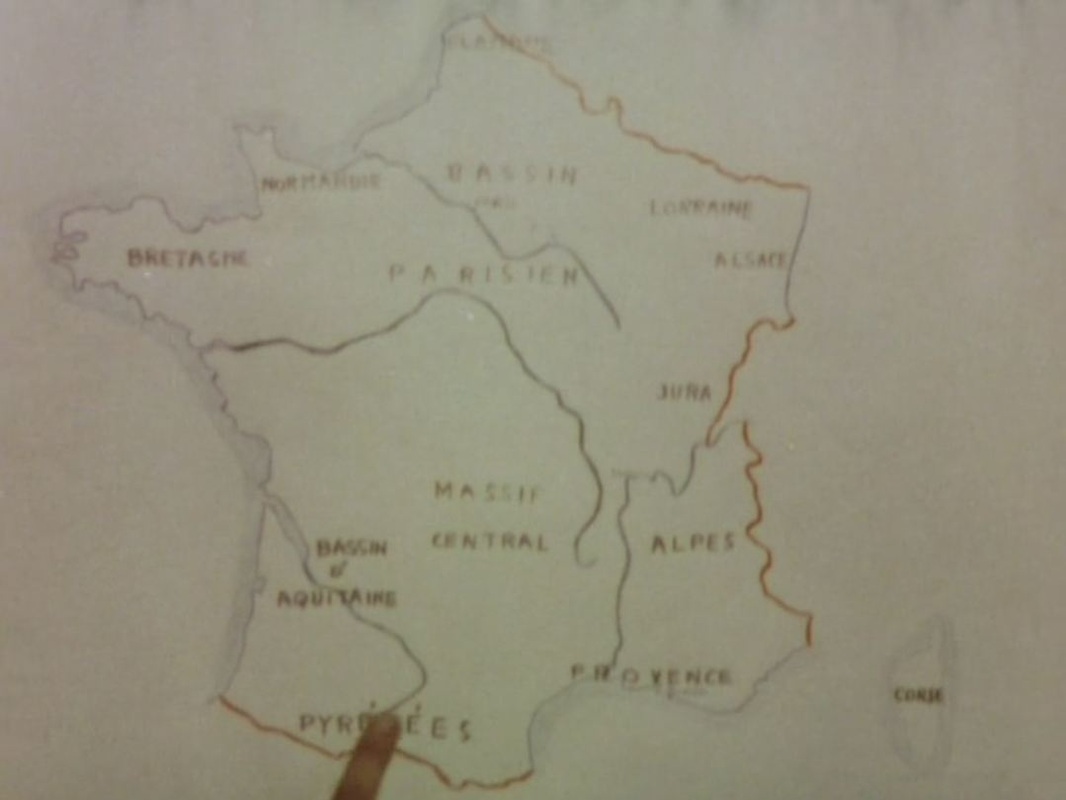

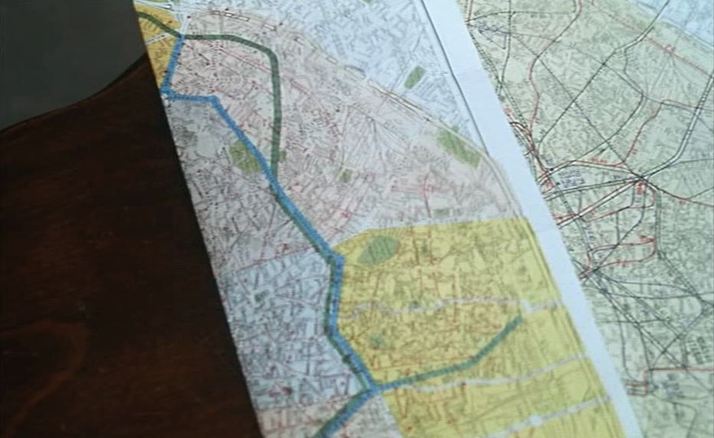

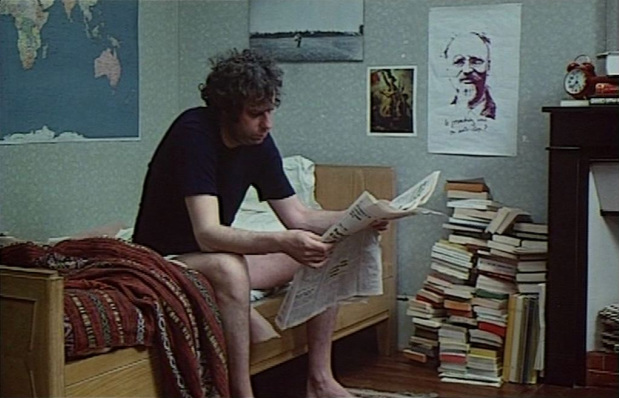

After pointing to relevant locales on the map of France, Moullet's New Wave documentary (reflexive, intertextual, montage-driven, jumpcutting) about abandoned or near-abandoned villages uses regional maps to fix exactly the places filmed, and to illustrate movement from one place to another: Two maps in the mise-en-scène, in schoolrooms, serve as counterpoint to the maps in the montage:

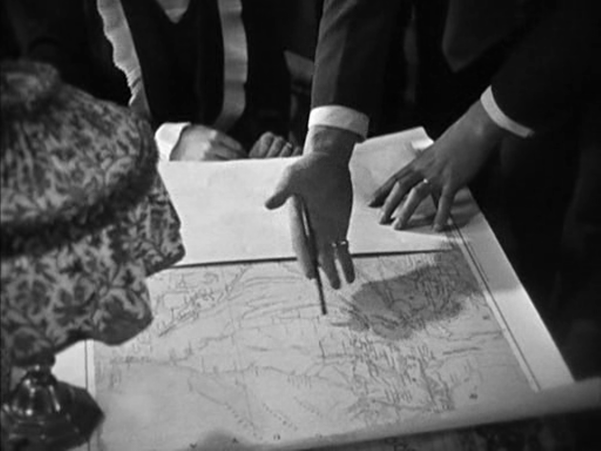

Frenchman Duvivier's 1944 war-effort film was made in Hollywood, and opens with a map expressive of the exile's gloom: France is cast in darkness. The map is closed in on, showing at first only Tours, strangely, then more obviously Paris, before following the line back from Paris to Tours, where the film's first action is set (explaining that town's prominence on the map). From there the protagonist's trajectory is followed South, whence he will eventually embark for Africa.

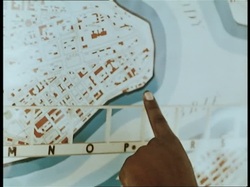

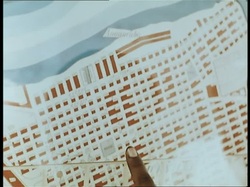

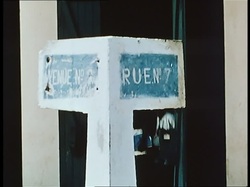

As the principal setting of the ensuing action, West Africa is on all the maps we then see. Most are in the mise-en-scène, though one is a cinemap tracing the protagonist's movements. (In its movement northwards it reverses the trajectory of the film's opening cinemap.) Arriving at Treichville, a district of Abidjan, we consult a map of the area, discovering the strict grid plan of the streets: Soon after, shots of signs indicating street names reveal a corresponding strictness in the district's nomenclature: But then we are taken beyond numbers and beyond the grid, and far from the Côte d'Ivoire:

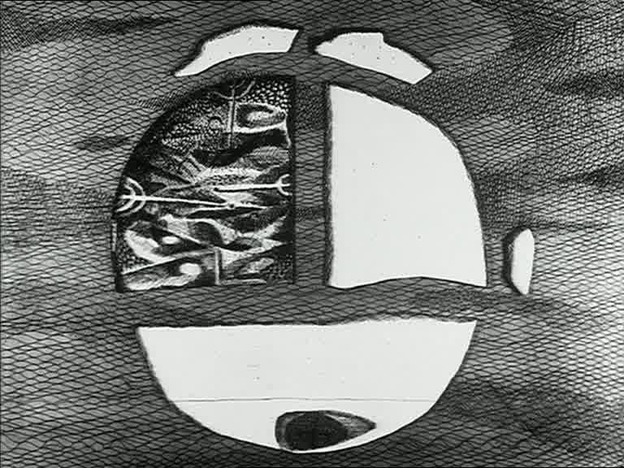

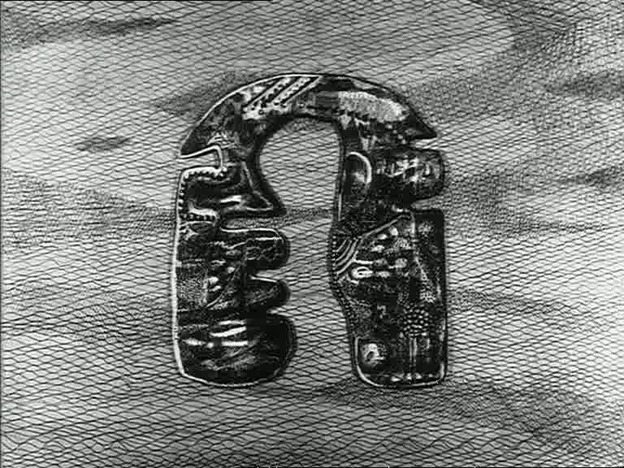

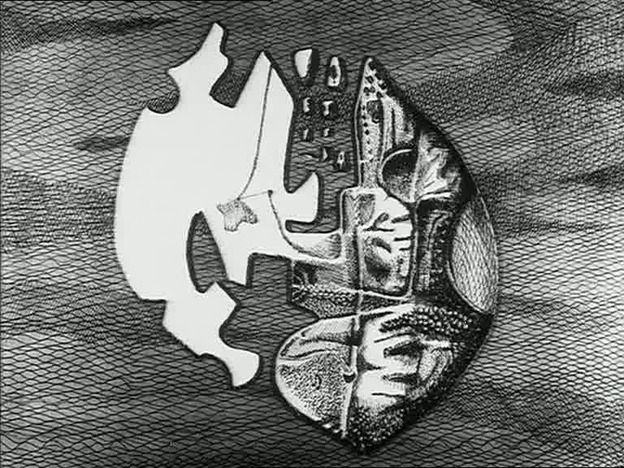

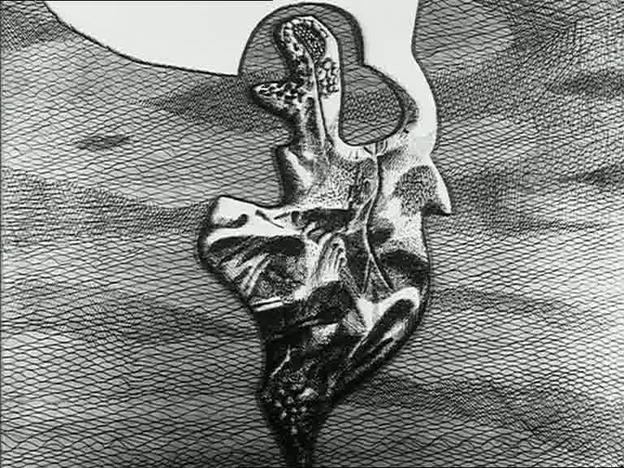

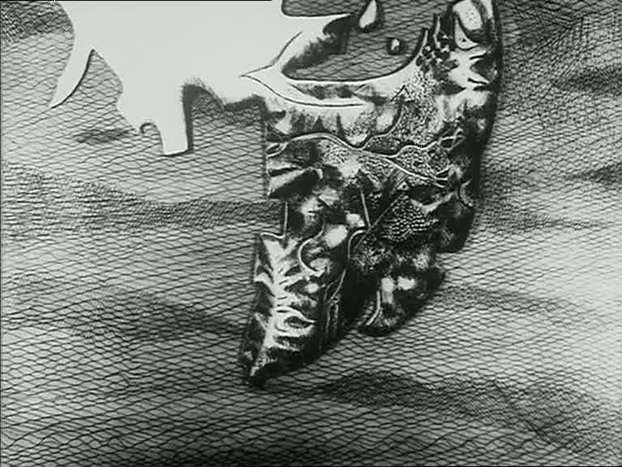

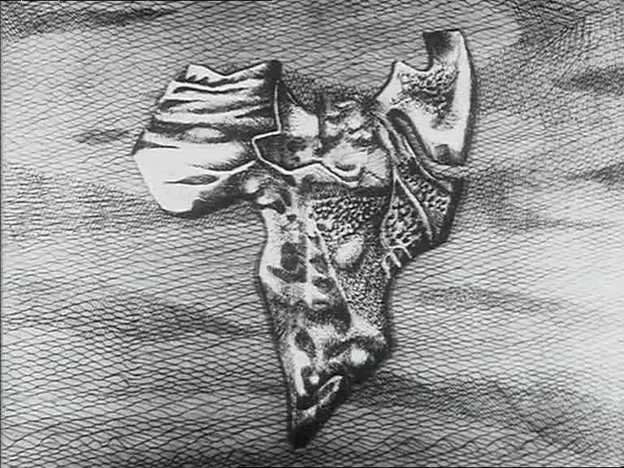

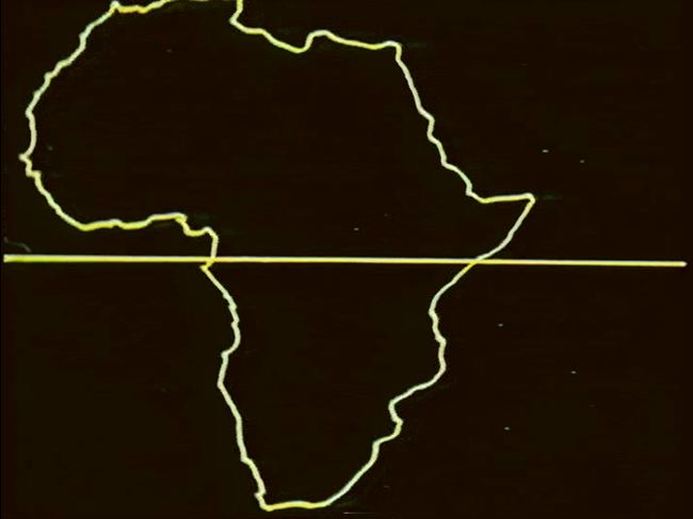

'The spectator’s gaze is further altered as he becomes a traveller into a voyage, "to a country where one goes by losing one’s memory" (vo). When he, the traveller-spectator, leaves European shrines of African statues deprived from their cultual context and assimilated through museologization, he is firstly brought in touch with different maps of Africa. The variety of maps depicting each in a different way the very same continent does not only show the relativity of all representation and hence the historicity of them (and also of the film). It also gives back what Africa is deprived of; namely history. To counter the idea in which – according to for instance Hegel in his Vorlesungen über die Philosophie der Geschichte – Africa is a continent without history, Les Statues gives a graphic insight of Africa’s evolution by showing its shape on the map slowly unravelling through the 11th, 12th, 15th and 17th century. This all proceeds from a map depicting Africa as "the fetus of the world" (vo) or "le nombril du monde" as Sartre puts it, the origin of the homo sapiens and archè of culture, which constitutes a ‘common ground’ for humanism to which Marker refers at the dénouement of the film.'

Matthias De Groof, ‘Statues Also Die - But Their Death is not the Final Word’, Image [&] Narrative, 11:1 (2010) (special issue on Chris Marker) Roma has no need of maps to orient us around the city.

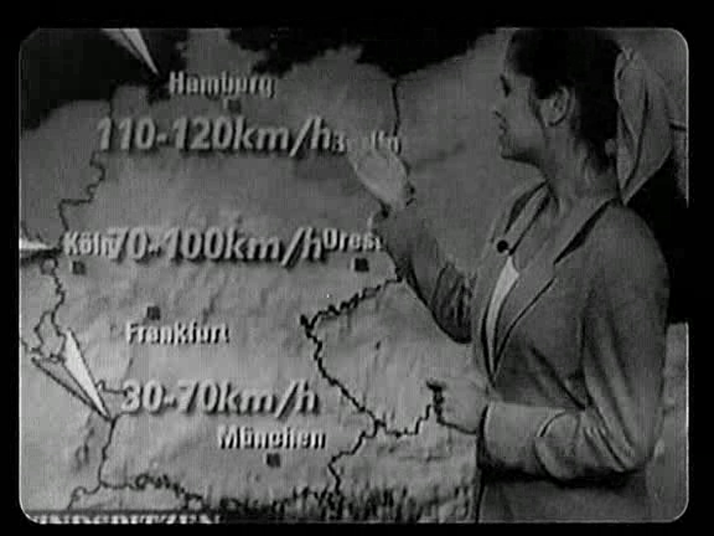

The only two maps in the film are details in a memory. That each occupies the same place in the frame allows us to read them together, even if the similarity is only a coincidence (about eight minutes separate them in the film). Of the forty films made with the Lumière camera that feature in this centenary homage, only two show maps. In Gaston Kaboré's contribution we see the silhouette of Africa on a poster for Darrell Roodt's film of Sarafina!: Michael Haneke captured television news images from the day of the centenary, including a map illustrating the weather report:

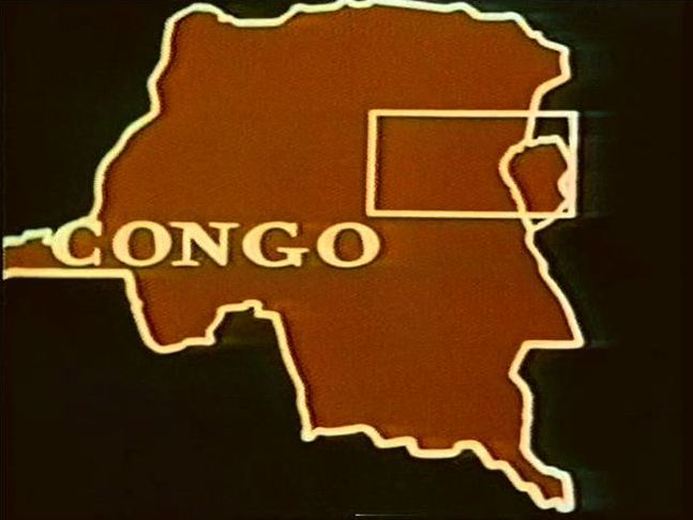

As large as as it looms behind the murderous protagonist, it is hard for us now to thematise this map of Africa. It seems incongruous in a film we remember for the beauty of Henri Decaë's cinematography, for the beauty of Miles Davis's score, and for the beauty of Jeanne Moreau.

At the time of the film's release, the critic Raymond Borde would have had no difficulty glossing this image. Here is what he wrote of the protagonist in Les Temps modernes (April 1958): 'Julien Tavernier, a captain in the parachute regiment who has served in Indochina and Africa. He left the army to become the right hand man of an arms dealer. His faithful batman still calls him "my captain" with a tremble in his voice. The memory of glorious round ups, of Oradour, of massacres and rapes. […] A modern hard man, a thirty-five year old paratrooper, a neo-Nazi capitalist, those are the three reference points of Louis Malle’s inner dream. In every sense of the word, Ascenseur pour l’échafaud is a Fascist film.' Maps often appear in television weather reports or news broadcasts, as background (as above) or foregrounded as a motif (as below): Here are eight further instances of maps on tv screens in films:

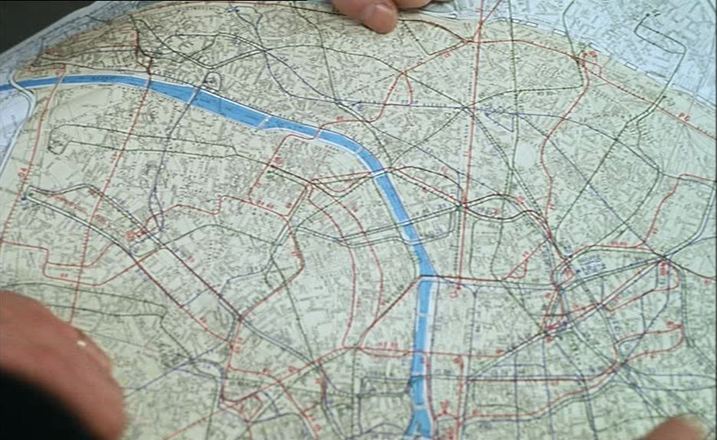

‘The evasion of reality is marked by Clive's two- dimensionalisation, as his substantial form is replaced on the screen by an ephemera, a walking shadow, an apposite nod to Macbeth, perhaps, for consequent upon the loss of his love, Clive's hunting life is a sound and a fury, a rampaging safari, signifying nothing. A similar montage immediately after the death of Clive's wife Barbara reinforces the point. Its status as a denial of historical progress is made clear as this second speeded journey through the inter-war period culminates in 1938 with a map of Munich and strains of the German national anthem. Clive later hangs Barbara's portrait in the 'den' along with his other trophies, emphasising what is now clear. It replaces, rather than proves, virility, and undoes Clive's self-appointed status as masculine epic hero.’ Andrew Moor, Powell & Pressburger: a Cinema of Magic Spaces (London: I.B Tauris, 2005), p.75 A 'Map of Lower Egypt and the Fayum' is the background to a scene from the time of Clive's 'masculine epic heroism': Maps of London are in the foreground of the events that will lead to his final emasculation:

‘A film is not its shots, but the way they have been joined. As a general once told me, a battle often occurs at the point where two maps touch.’

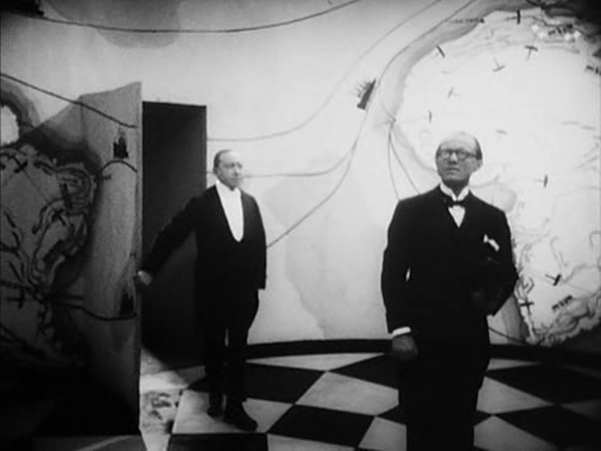

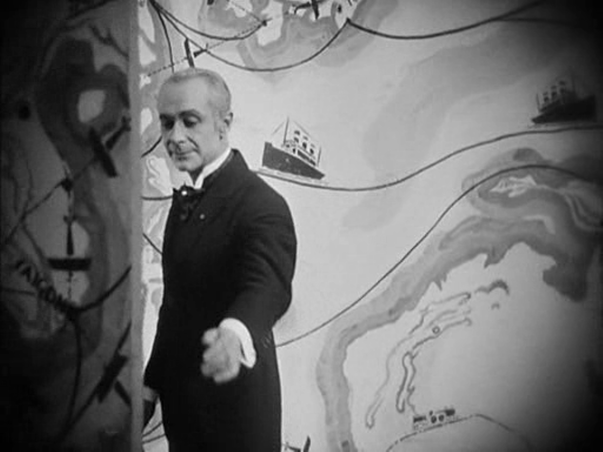

Robert Bresson, ‘Encountering Robert Bresson’, interview with Charles Thomas Samuels, republished in The Films of Robert Bresson: Casebook (London: Anthem, 2009), p. 96. Below are more maps from Bresson films. Of the five spaces in which maps figure in L'Argent, the first is the most spectacular. We follow an agent of the banker Gundermann as he is led by a butler into an antechamber decorated to represent the reach of the banker's power. In combination with the cinematography, this mise-en-scène also displays the distorting, disorienting force of money. The second space is more conventional: in their modest apartment. the naive adventurer hero Hamelin and his wife Line examine a map of the Americas, though it becomes a mere backdrop to the expression of their love for each other. Later, in the same space, Hamelin explains his plans to the banker Saccard, with a view of a more detailed map of the region that Hamelin proposes to exploit for oil. We first see the scene diffusely, in a mirror, before passing to two readable mapshots. Next, in a room at the airport from which Hamelin will take off on a solo flight across the Atlantic, Line looks on in terror at the thought of the danger he will face. He enters, first seen as a shadow cast over a map of Europe and North Africa, which then becomes the backdrop to their passionate embrace on parting. The most often shown space in the film is the banker Saccard's office, dominated by a map of the world. Against this backdrop we see Saccard manipulate markets on a global scale, we see him attempt to seduce Line, and finally we see him arrested for fraud. Prior to Saccard's arrest we see Hamelin in Guyana (here with Antonin Artaud as Saccard's secretary). A map on the wall serves as establishing decor, but it cannot compete with the cartographic spectacles on display back in Paris. Hamelin returns to France and we see two policemen waiting to arrest him in the same room at the airport where he had kissed Line farewell. This time we see more of the cartographic decor, including the west coast of France: The film's denouement involves Line approaching Gundermann, and we see again, in more detail, his spectacular antechamber: The decor of L'Argent is one of Lazare Meerson's finest achievements, especially in the cartographic configurations of this last, framing space.

When, in 2011, I first posted about the maps in this film I said they appeared in only one scene. Seeing the film again this afternoon at the ICA, in a beautiful print, I spotted my mistake in not spotting the very large globe, above. Many thanks to The Badlands Collective for organising the screening, on the film's 40th birthday. Maps appear in Barry Lyndon in only one scene, but they cover the known world, from Asia through Africa and Europe to the Americas. And there is a globe on the table in front of the first map.

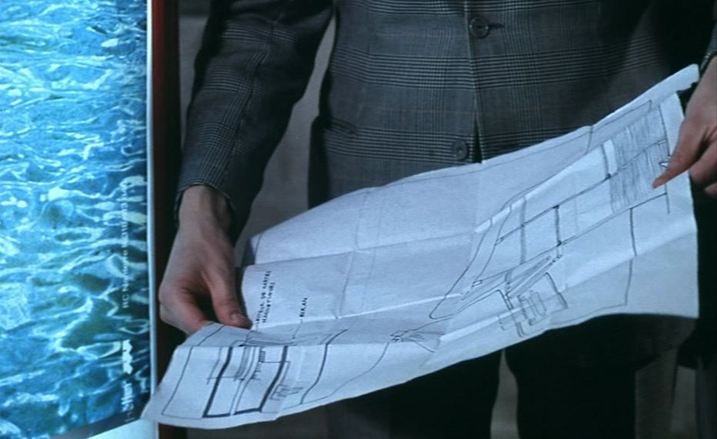

‘In Lindsay Anderson's 1973 O Lucky Man!, starring Malcolm McDowell, British imperialists meet with a Third World dictator for a presentation about foreign investment and labor conditions in the fictionalized African nation of Zinagara. British actor Arthur Lowe, in blackface, plays African strongman Dr. Munda. His economist narrates an audiovisual account of Zingara's free export zone, offering foreign investors excellent labor conditions: peon wages, the illegality of strikes, no income tax. Sir James Burgess (Ralph Richardson) asks if there's the “threat of insurrection?” Germanic Colonel Steiger shows another film, about a counterinsurgency campaign against rebels. The essence of the transaction is that Dr. Munda and Colonel Steiger want to grant Burgess the rights to construct resorts along Zinagara's coasts, in exchange for napalm which the African dictator will deploy against insurgents.’

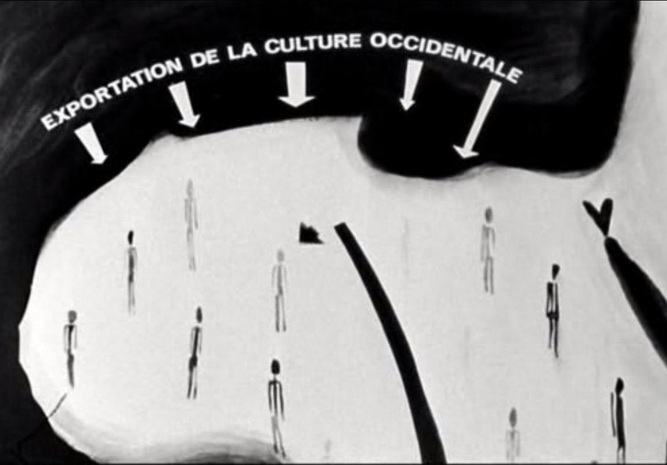

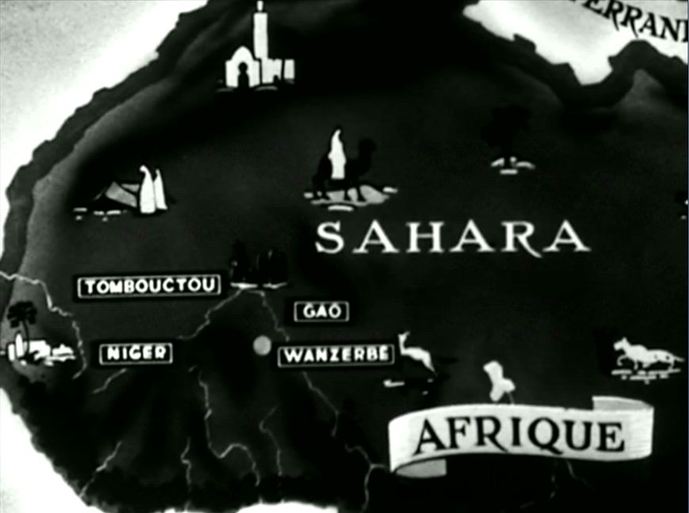

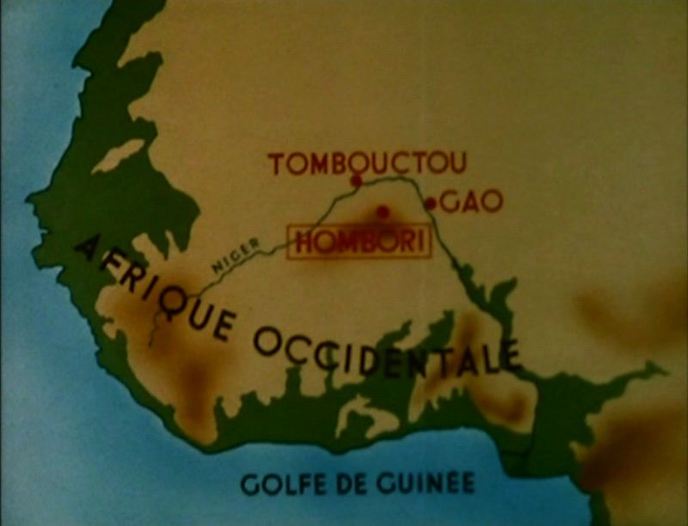

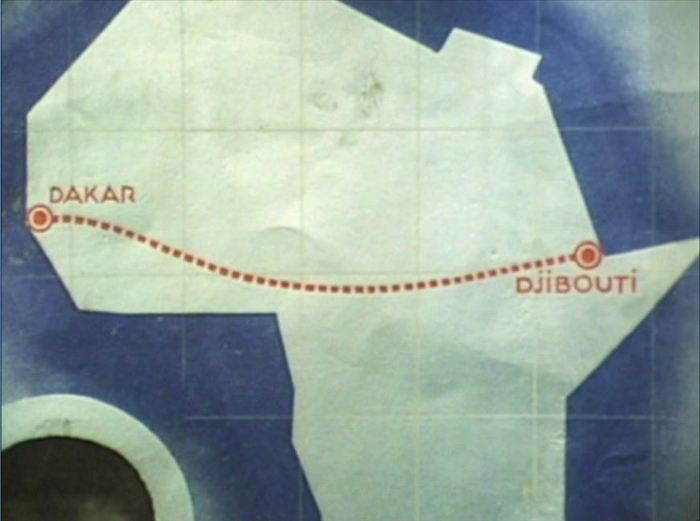

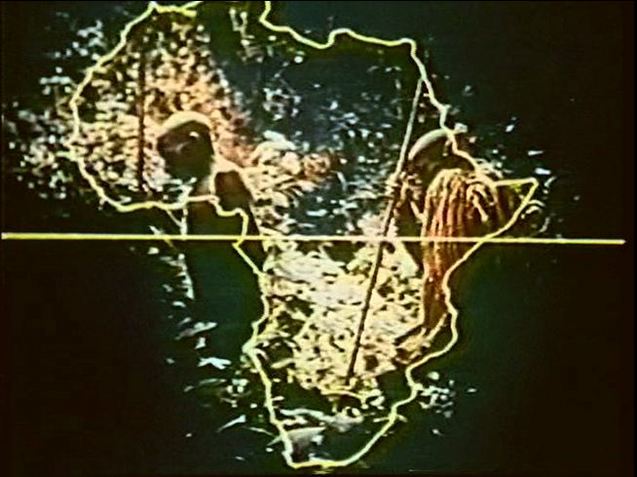

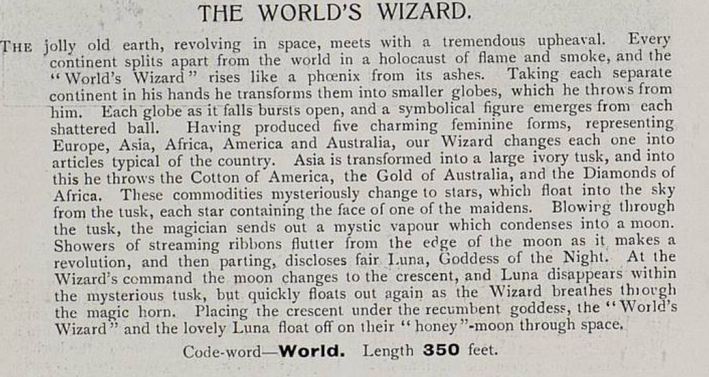

Ed Rampell, Progressive Hollywood: a People’s Film History of the United States (New York: The Disinformation Company, 2005), p.105. Hondo's cinemap is a response to and critique of the graphic representations that typically introduced European ethnographic films on African cultures (see examples below).

‘After a credit sequence showing belle époque photographs three “nationalist” recitations are juxtaposed, before a map presents insistently the gaping wound that is Alsace Lorraine: the lies of propaganda, the desire for revenge, and then there is war.’

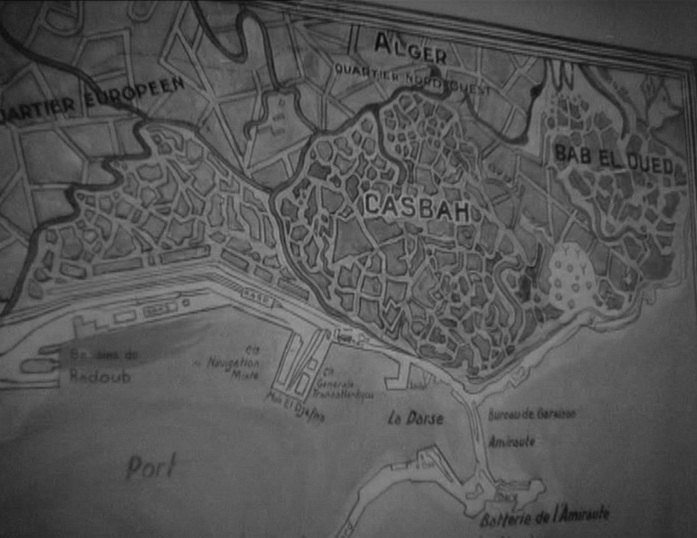

Corinne Françoise-Denève, ‘Retour de flamme: Grande Guerre et cinéma français dans le nouveau siècle’, in Carola Hähnel-Mesnard, Marie Liénard-Yeterian, Cristina Marinas (eds), Culture et mémoire: représentations contemporaines de la mémoire dans les espaces mémoriels, les arts du visuel, la littérature et le théâtre (Palaiseau: Les Editions de l’Ecole Polytechnique, 2008) p. 186. ['The image of the map in Pépé le Moko promises to locate the viewer in a position of mastery.']

‘If, as de Certeau proposes, a "space" is defined by a hero's "direction of existence," then the opening of Pépé le Moko suggests a situation in which this hero is none other than the film’s viewer. That is, the movement from the neoclassical "place" of the police station to the primordial "space" of the Casbah is also a movement away from classicism's stable distance between beholder and spectacle and toward an indeterminacy in which scientific distance alternates with a kind of tactile convergence.’ Charles O’Brien, ‘The “Cinéma colonial” of 1930s France: Film Narration as Spatial Practice’, in Matthew Bernstein & Gaylyn Studlar (eds), Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film (Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997), p.210. 'Many contemporary filmmakers use techniques of prettiness to access the politics of world. Abdherramane Sissako, for instance, presents in Bamako (2006) a richly textured map of global economics within the visual and auditory space of an African village. (…). Sissako uses decorative patterns and colors to form a dynamic social cartography.'

Rosalind Galt, Pretty: Film and the Decorative Image (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), p.27 'In unmistakably cinematic terms, the maps of Africa function as frames displaying this contrast and movement through the juxtaposition of different graphically rendered realities. The map, for Frobenius, is an adequate representational form only insofar as it captures the kinematographic element, the fact that cultures can only be comprehended as constantly in motion. “Since culture is kinematographic”, Frobenius suggests, “the map must become kinematographic”.’

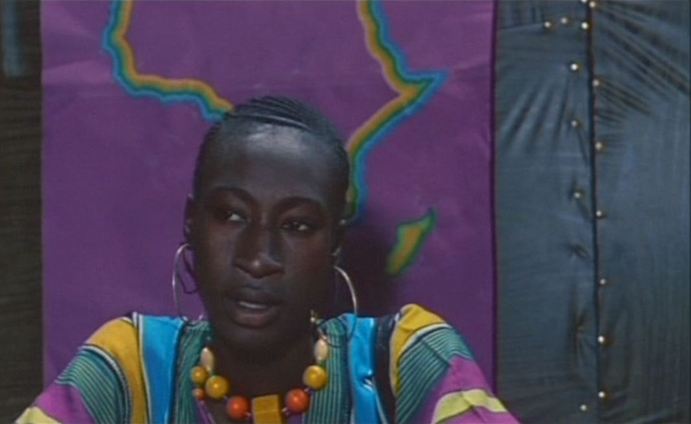

Assenka Oksiloff, ‘Leo Frobenius and Kino-Vision’, in Picturing the Primitive: Visual Culture, Ethnography and Early German Cinema (New York: Palgrave, 2001), p.109. ‘Before Rama stands up to walk out of the frame Sembene makes us take note of the map of Africa behind her once again. We notice too that the color of the map reflects the exact same colors of Rama's traditional boubou (native costume — blue, purple, green and yellow — and it is not divided into boundaries and states. It denotes pan-Africanism:

El Hadji: My child, you don't need anything? [he searches his wallet] Rama: Just mother's happiness [she then walks out of the frame as the camera lingers on the map] What Sembene is saying to us is quite direct and no longer inaccessible. On one level, Rama shows concern for her mother — it occupies a place of meaning in the dialogue. On another level, when we consider the African map which occupies the same screen space as Rama, her concern becomes not only her maternal mother but “Mother Africa”. This notion carries an extended meaning when we observe the shot of El Hadji — to his side we see a large colonial map of Africa.’ Teshome Gabriel, Third Cinema in the Third World: the Aesthetics of Liberation (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1982), pp.83-84. ‘In nearly every interior he painted, there is either a map, a sheet of music, a letter, a chart, or a picture whose subject-matter functions like an ideogram.’

John Berger (writer of Jonas qui aura 25 ans...), 'The Painter in his studio: Vermeer', in The Moment of Cubism and other essays (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1969), p.77. |

|