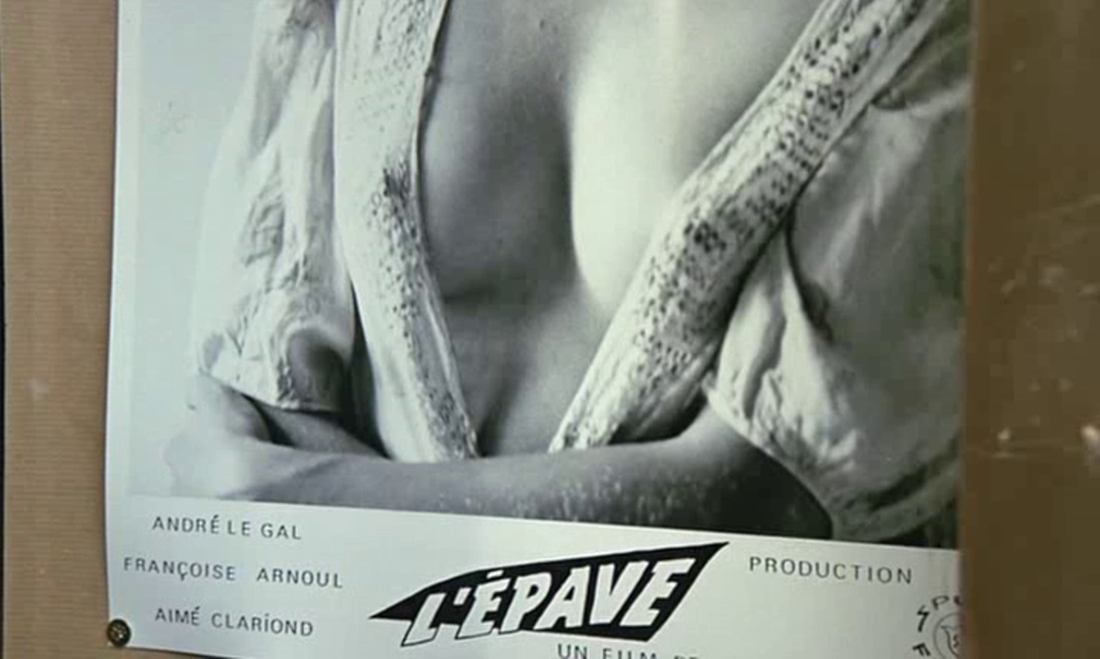

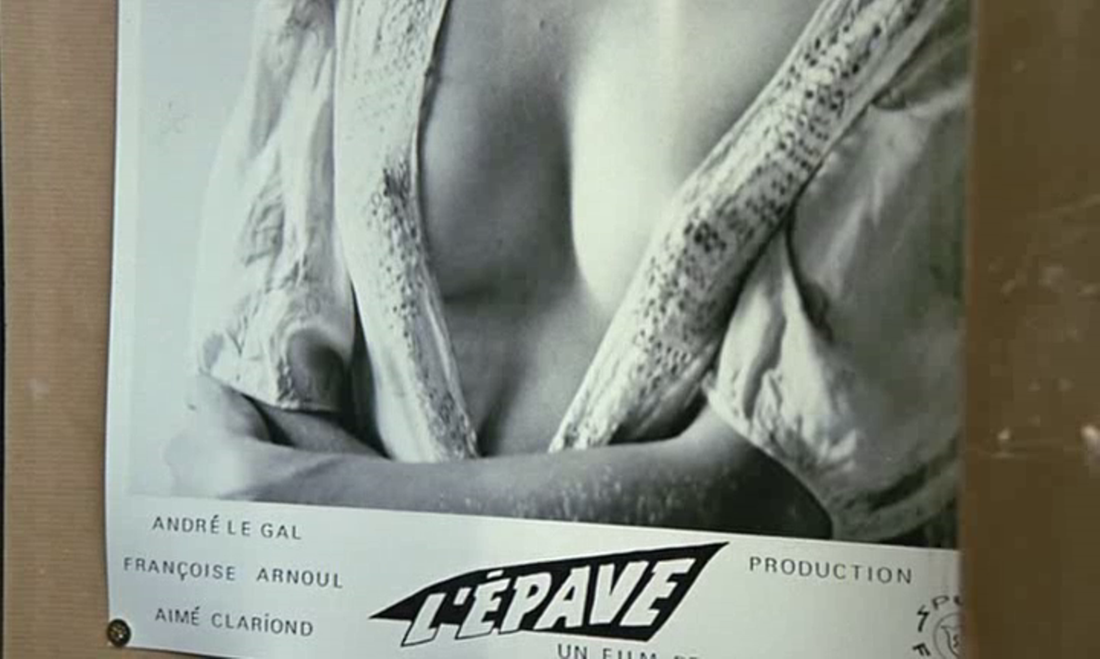

In Claude Miller's 1950-set film La Petite Voleuse, Janine (Charlotte Gainsbourg) compares her appearance to that of Françoise Arnoul, seen in a foyer-photograph for Willy Rozier's L'Epave, as she stands in the entrance to a cinema:

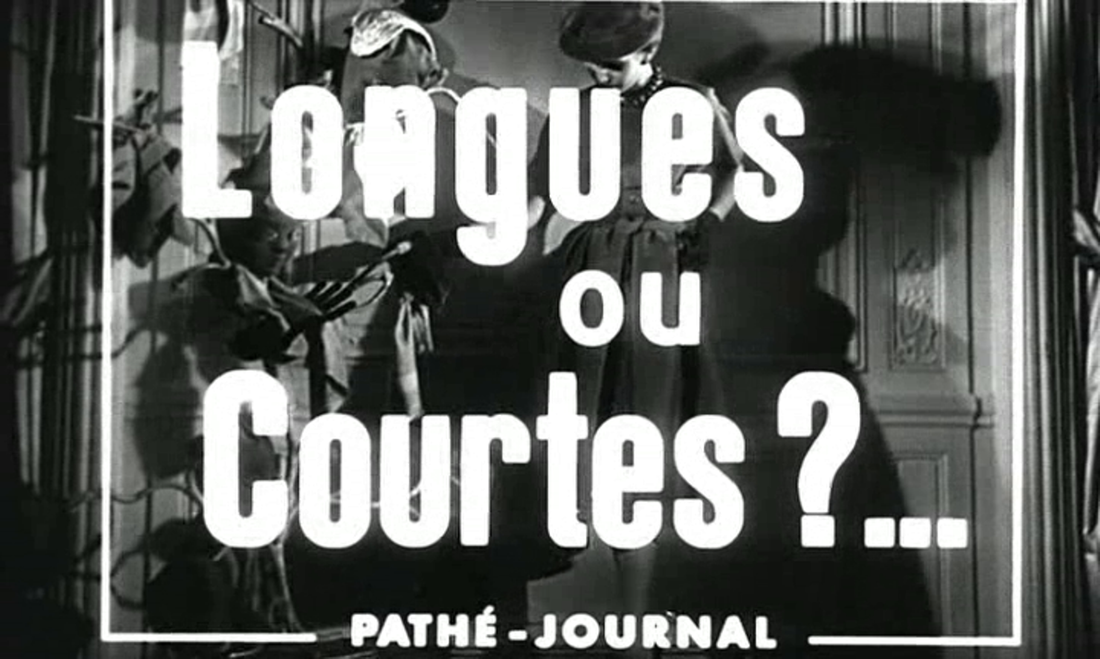

Released in 1949, L'Epave fits the chronology of La Petite Voleuse, but other films referenced by Miller do not. In the entrance to the cinema is a poster for a forthcoming attraction:

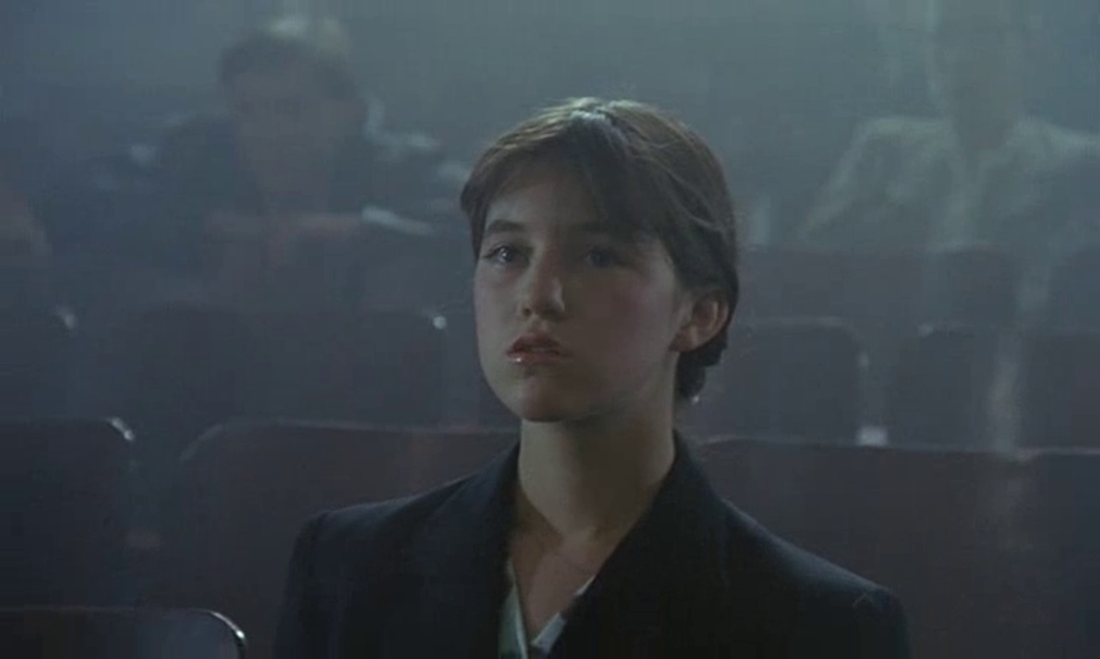

That La Petite Voleuse isn't troubled by anachronism is apparent when Janine goes to the cinema to watch a film called 'Passion Eternelle':

We see nothing of the screen, and the dialogue and music are composed for Miller's film, rather than retrieved from the past. We know the title of the film she is watching from the poster in the foyer:

| This is in fact a poster for David Lean's 1955 film Summer Madness, called in France Vacances à Venise. I can find no evidence that this film was ever called Passion Eternelle in France, but I cannot imagine that someone went to all the effort of doctoring the original poster, so actually I am stuck for an explanation. (Suggestions here, please.) |

(For more information about the cine-references in La Petite Voleuse see the dedicated page at Cinéclap, here.)

This discussion is just a preamble to what really interests me in this confluence of intertexts, which is Willy Rozier's 1949 film L'Epave, the only accurate period reference among the films mentioned in La Petite Voleuse.

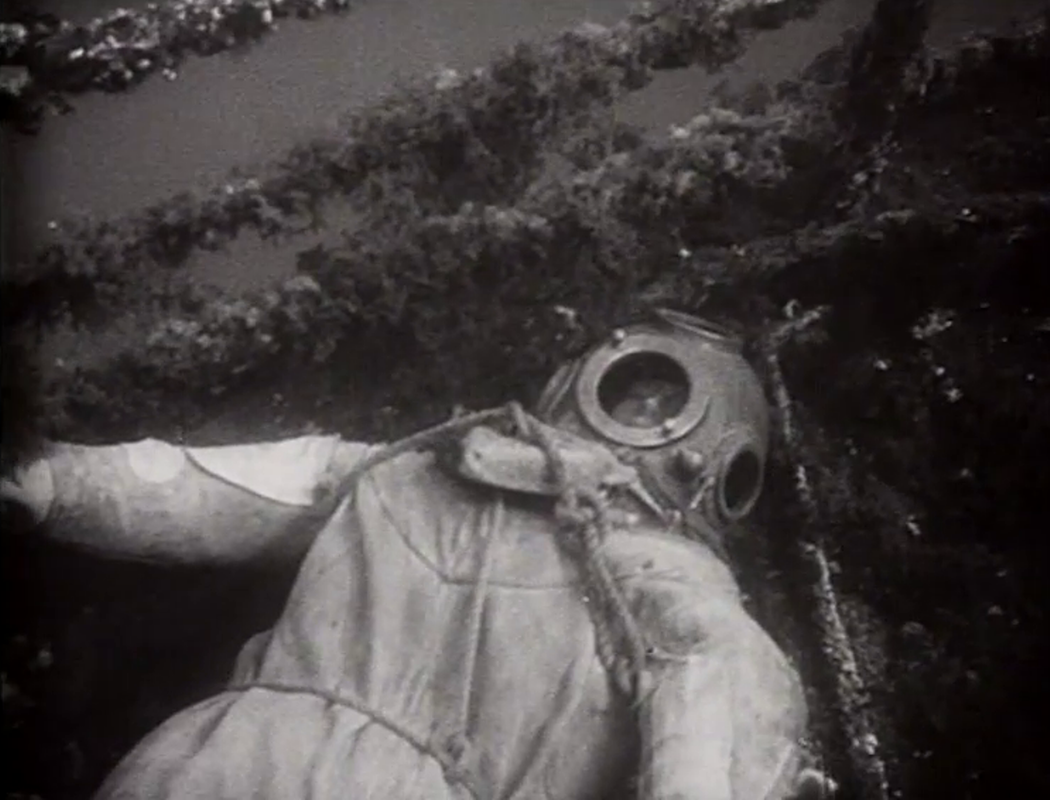

There are at least five aspects of the film that warrant attention. The use of voice-over is striking, in particular the closing words, spoken by the man we have just watched commit suicide in a deep-sea diving suit:

There are at least five aspects of the film that warrant attention. The use of voice-over is striking, in particular the closing words, spoken by the man we have just watched commit suicide in a deep-sea diving suit:

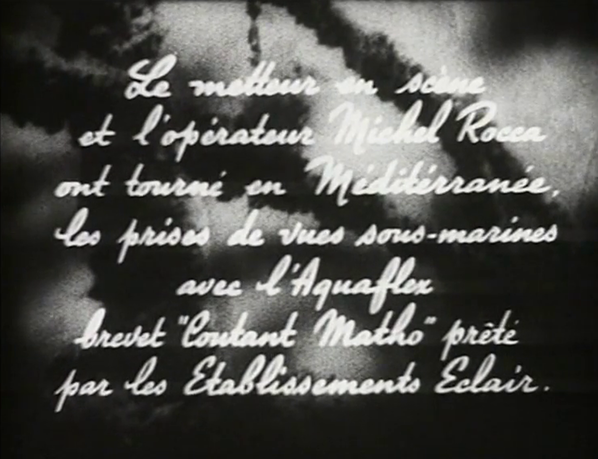

Unfortunately, I cannot in this post effectively illustrate the creative variety of the film's soundtrack. The maps I have already sampled here. The film itself, in the credits, foregrounds the innovative underwater camera work, using the Eclair Aquaflex, a newly patented camera by Coutant:

Just as remarkable, however, is the nudity in the film, made into a reflexive device when Perrucha (Françoise Arnoul) is told to undress for an audition:

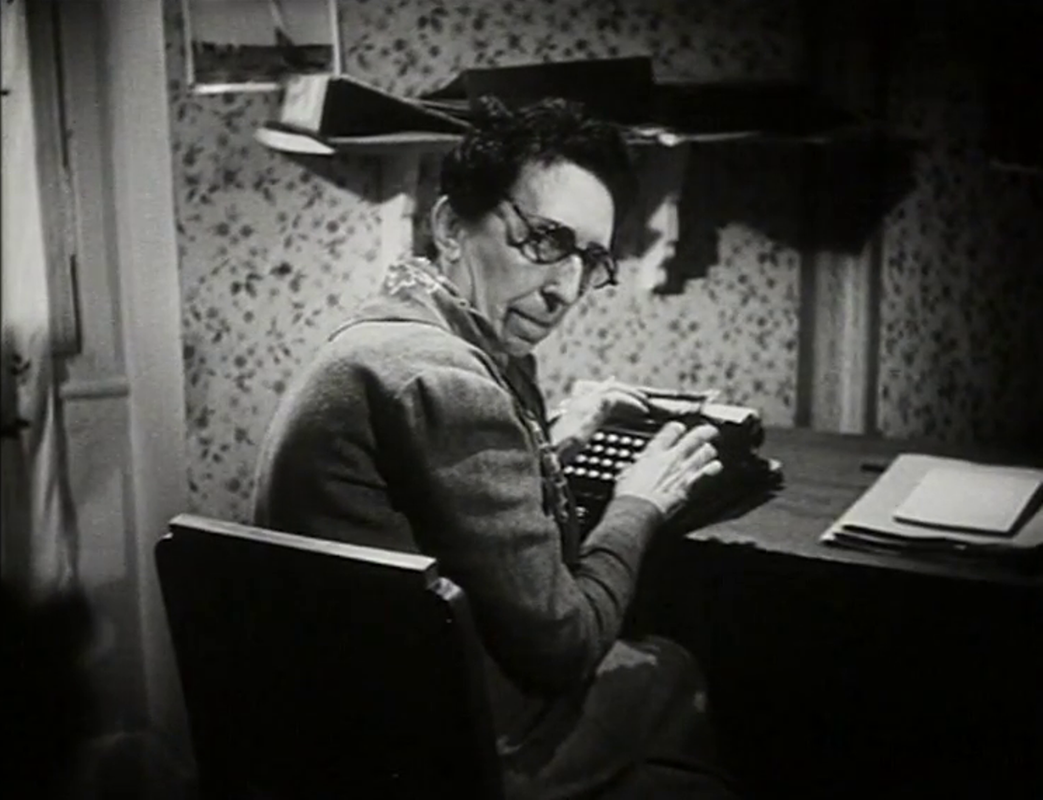

This sequence is characterised by varieties of gaze: the relative indifference of the man auditioning Perrucha ('I don't give a toss about your arse, I've seen fifty today'); the furtive scrutiny of the secretary; Perrucha's looking away from then directly at the man, and, self-reflexively, the camera's own tilting gaze, from her feet to her upper body:

Her physique gets her hired but she refuses the job, saying that she doesn't want to display herself to people, she wants to sing and dance. The film will allow her to sing and dance, but it will also display her, naked, to its audience:

The same irony is at work later when, in the cabaret where she is working, one of the acts sings, dances and performs a strip:

This striptease ends before the performer is completely naked, as if the film were sharing her coyness before the public, while it is otherwise, in private, happy to undress its leading lady.

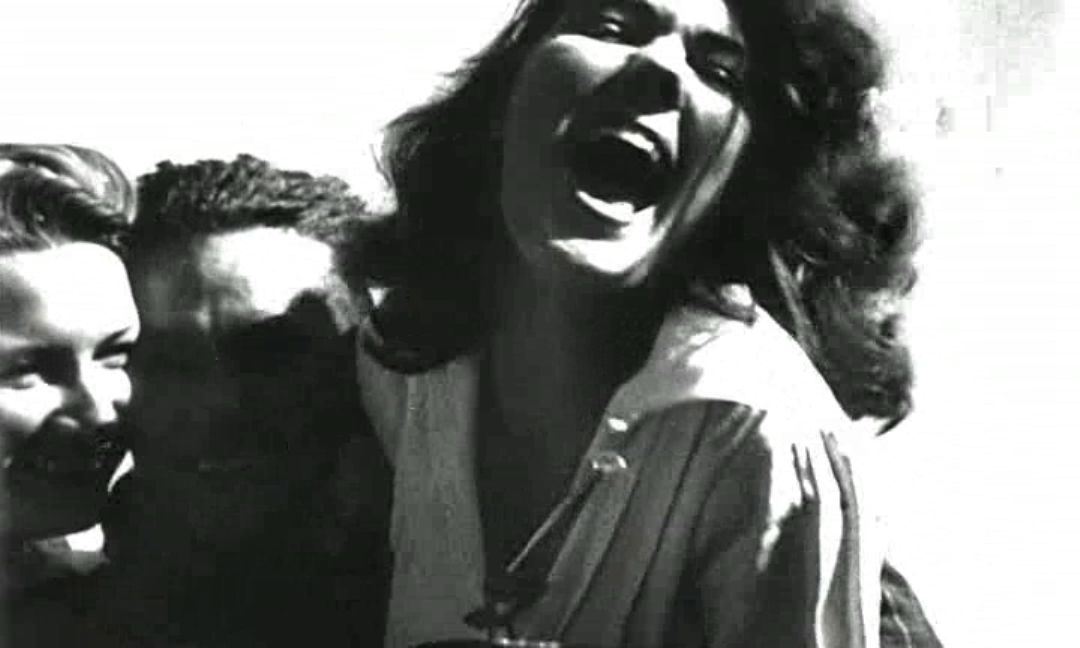

More interesting, though, than maps, underwater cinematography or nudity, I would say, is the film's fixation on the look to camera, in particular on the gaze of Françoise Arnoul:

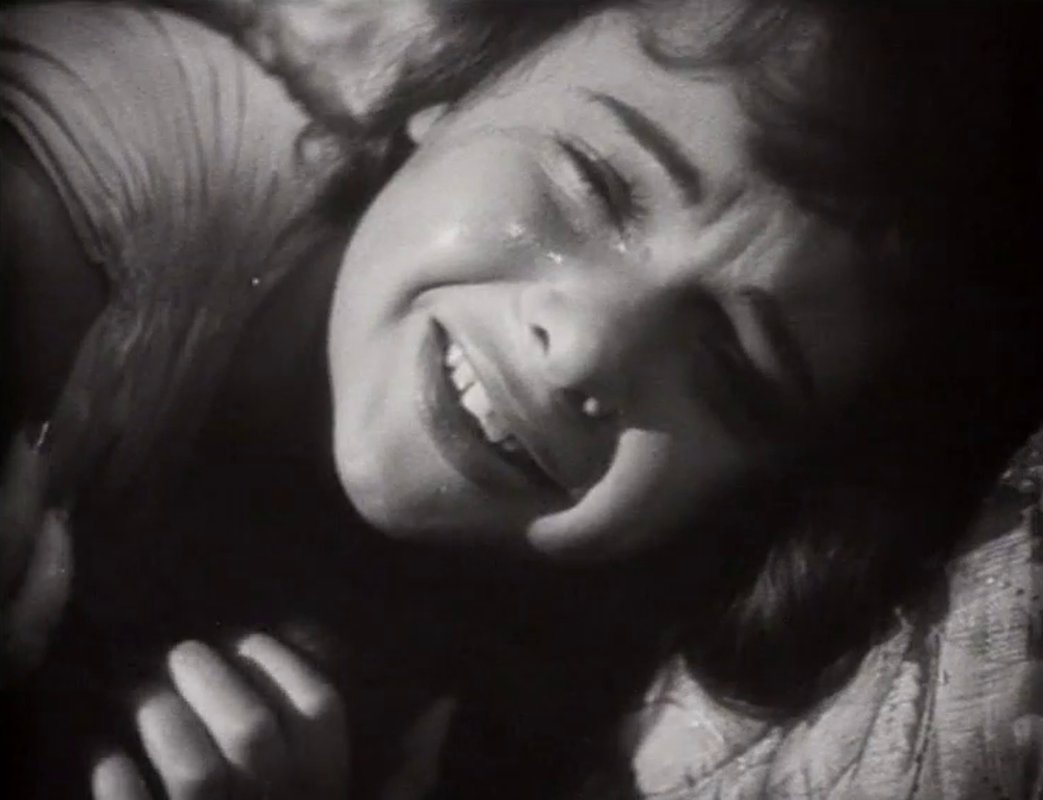

Four of these looks to camera signify in conjunction with the soundtrack: the first is accompanied by applause as she imagines her success as a performer; the second is accompanied by silence as her lover, Mario, suggests they marry (she then closes her eyes, and we hear the whistle and engine of a locomotive); the third and fourth add expression to the song she sings (in a radio studio, then on stage). The last is more straightforward - she is hysterical because her lover is going to kill himself, thinking he has killed her.

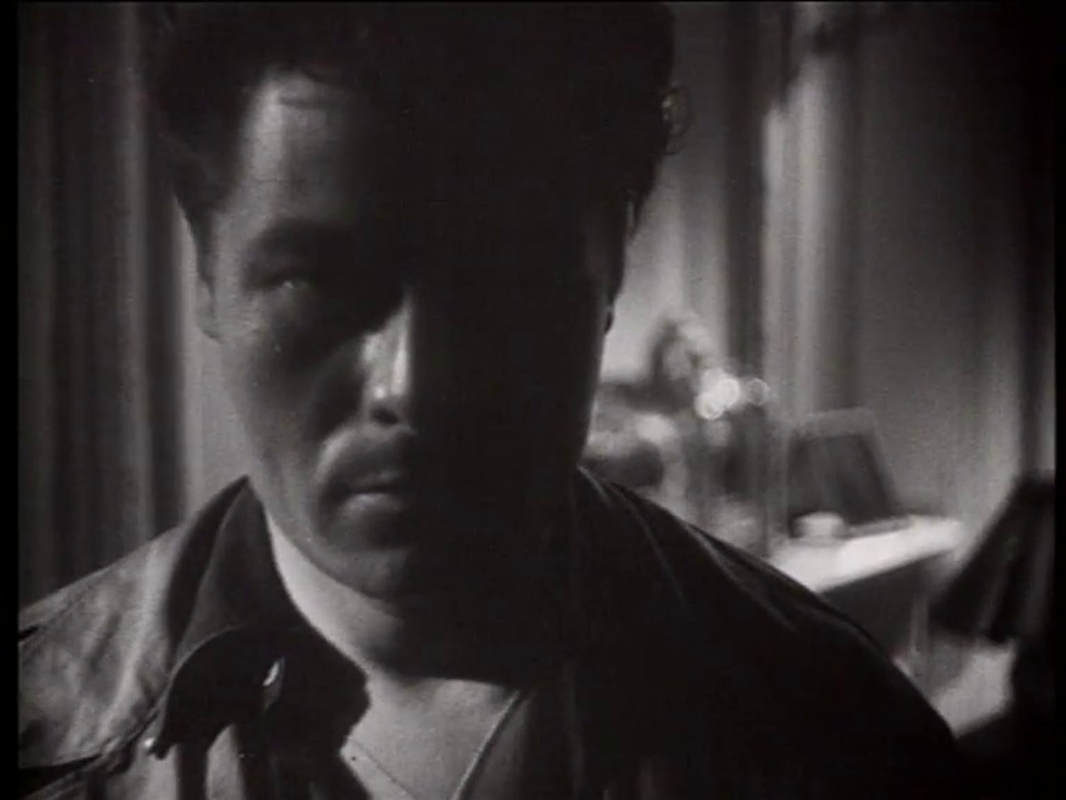

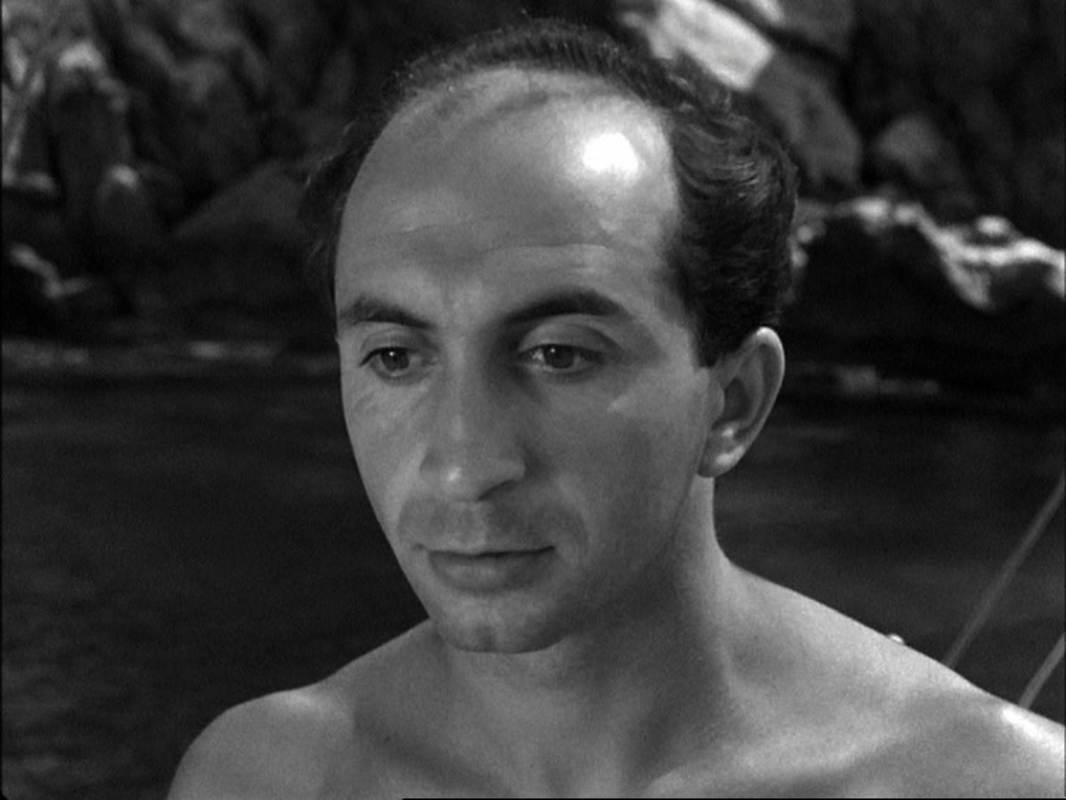

The fifth of these fourth looks is from the climax of the film, when Perrucha's lover strangles her. This sequence thematises the look to camera, firstly in that she doesn't recognise him. He approaches the camera, an extreme close-up that the next shot allows us to read as her point of view:

The fifth of these fourth looks is from the climax of the film, when Perrucha's lover strangles her. This sequence thematises the look to camera, firstly in that she doesn't recognise him. He approaches the camera, an extreme close-up that the next shot allows us to read as her point of view:

Mario takes her in his arms and says 'Regarde moi bien', 'Look at me':

A suggestion of reconciliation accompanies a look to camera in extreme close-up:

His gaze falls on her open nightgown, returning us to the film's fixation on Arnoul's nudity, here thematised in conjunction with the intensity of the fourth look:

This moment was isolated for a promotional film still, the one that provokes a reaction from Janine in La Petite Voleuse:

Perrucha's reaction is to cover her breasts:

Mario's anger returns when she refuses to have sex with him one more time (before he kills himself), and he strangles her. As he leans over her seemingly lifeless body the soundtrack echoes the locomotive sounds heard forty minutes earlier, and the intensity of her gaze is transferred to him:

I know of no film of this type or period so intensely centred on the look to camera, nor any so 'daring', as the publicity puts it, in its display of nudity. Three years later, Rozier directs Brigitte Bardot in a film that promises nudity in its title, Manina ou la fille sans voile, but which delivers only a succession of louche men ogling Bardot in her bikini:

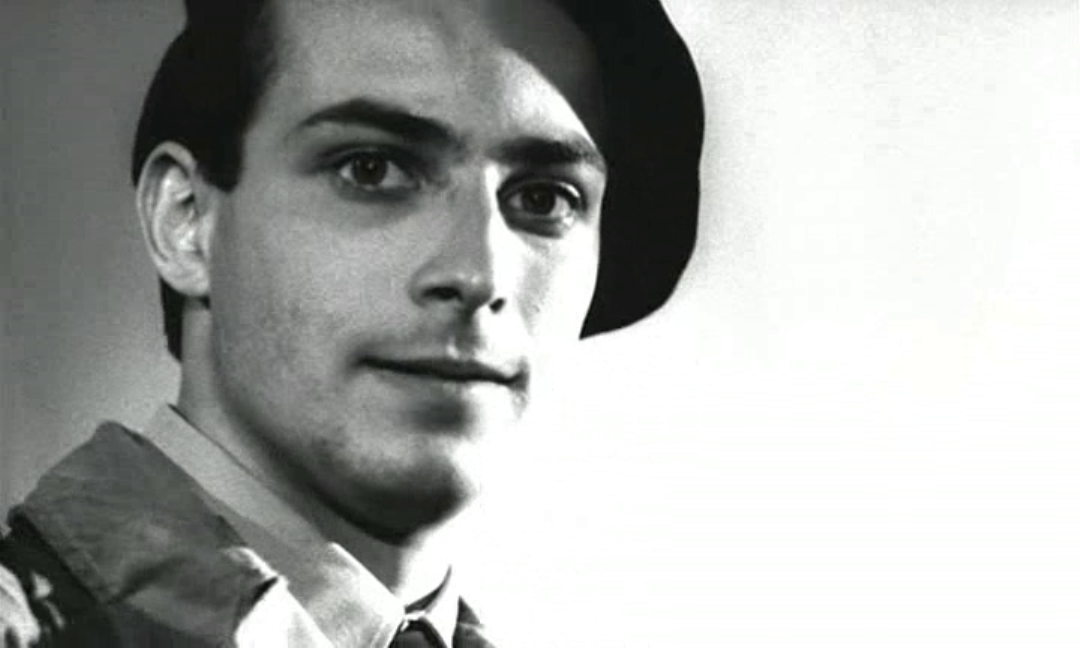

The look to camera is reserved, in 1950s French cinema, for comic asides, most often as the film closes, for example in Bernard Borderie's Lemmy Caution films:

Or in Michel Boisrond's Une Parisienne:

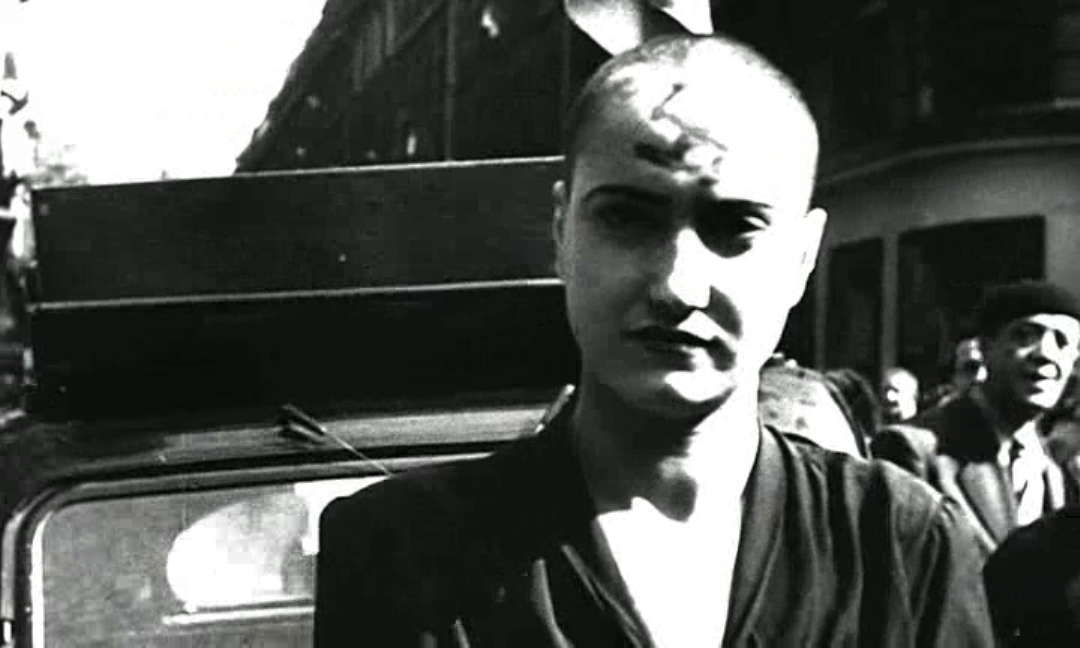

Aside from this glimpse of Janine in a mirror, looks to camera in La Petite Voleuse occur only in the authentic newsreel footage shown near the beginning of the film:

And in the fake newsreel watched by Janine towards the end of the film:

Despite being made almost forty years after L'Epave, La Petite Voleuse is much more reluctant to show its female star naked:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed