|

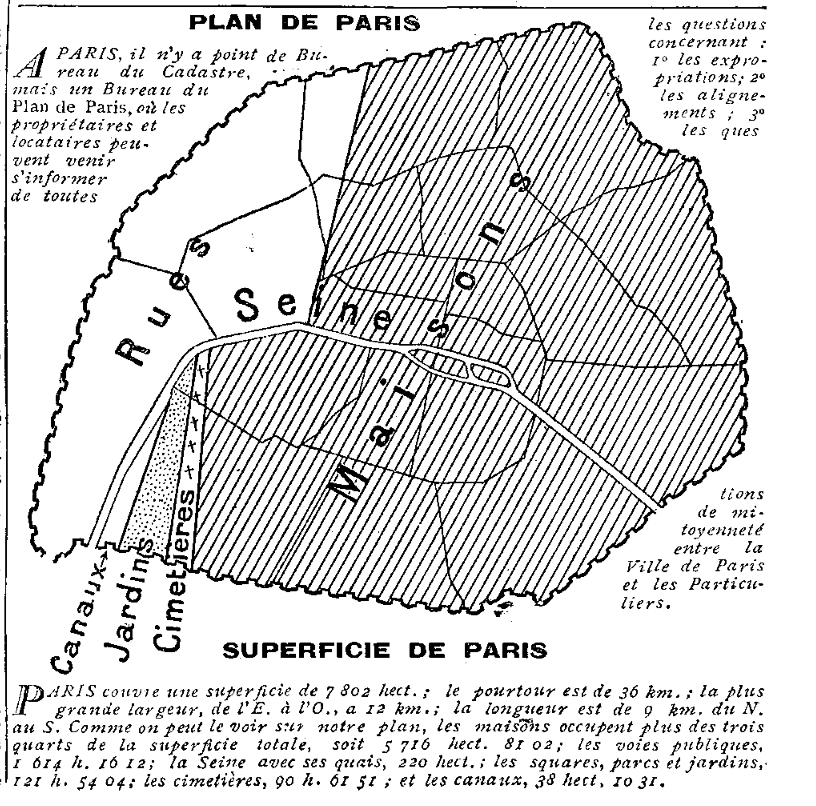

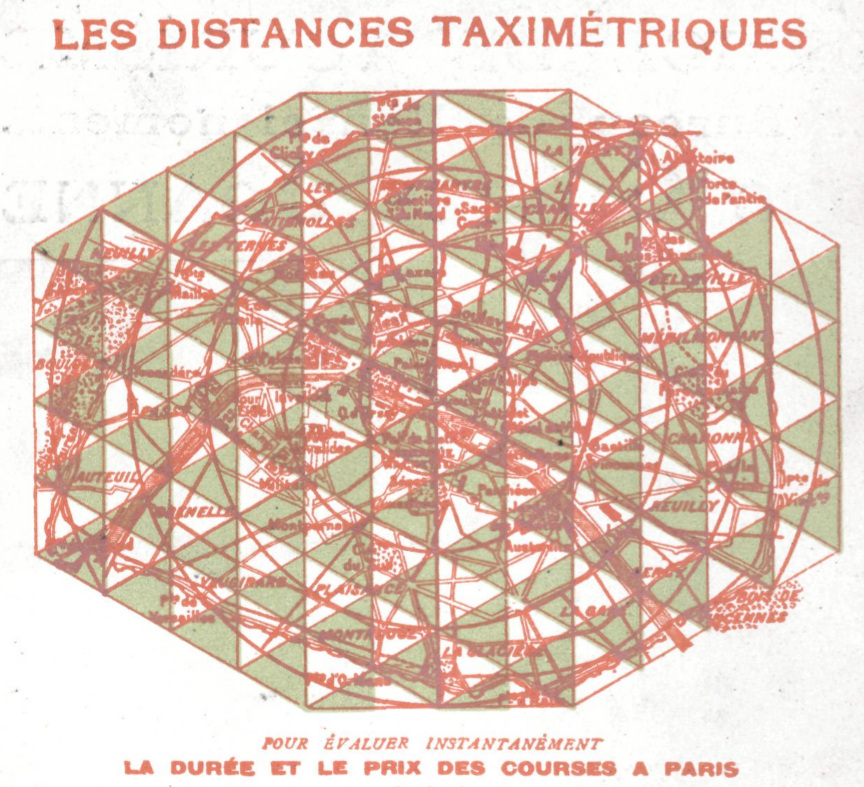

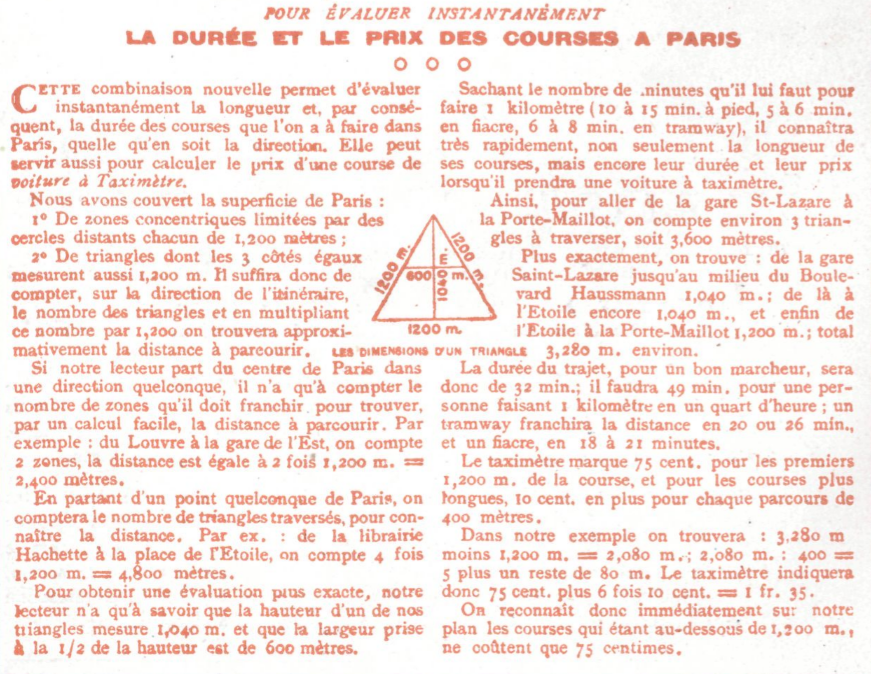

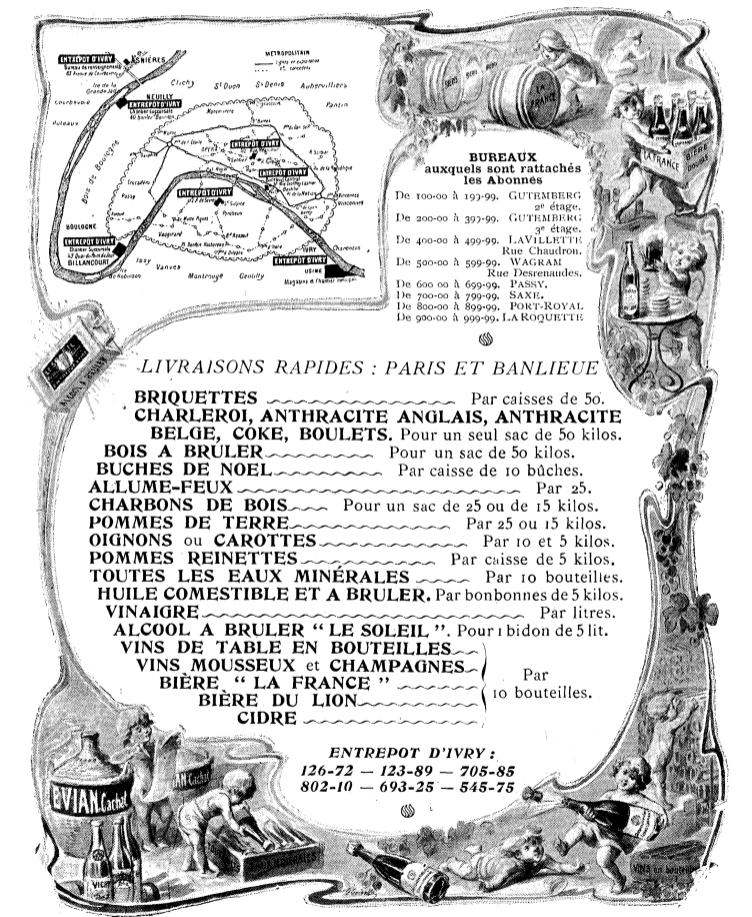

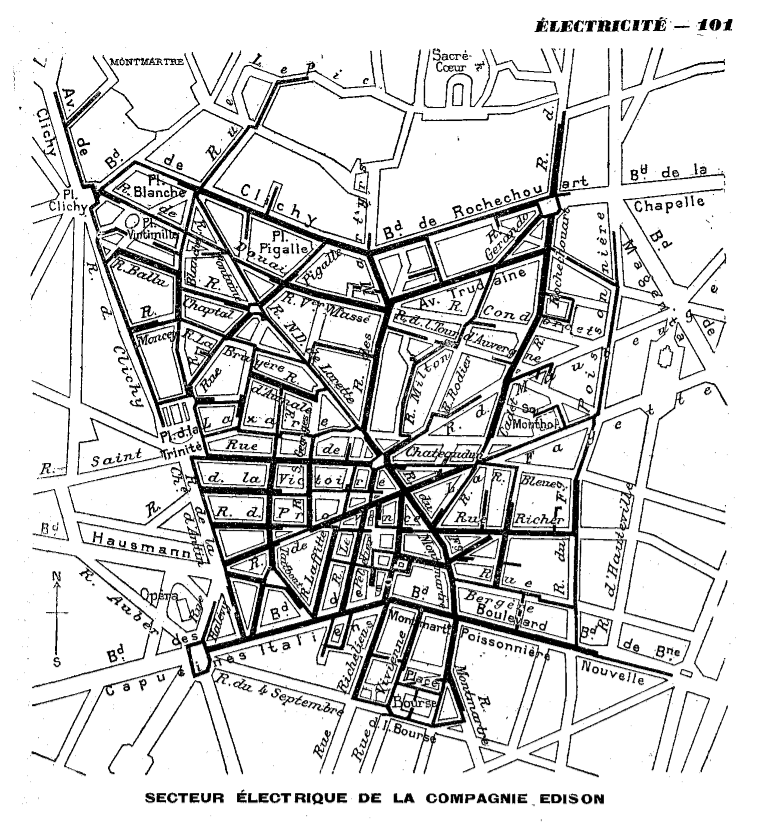

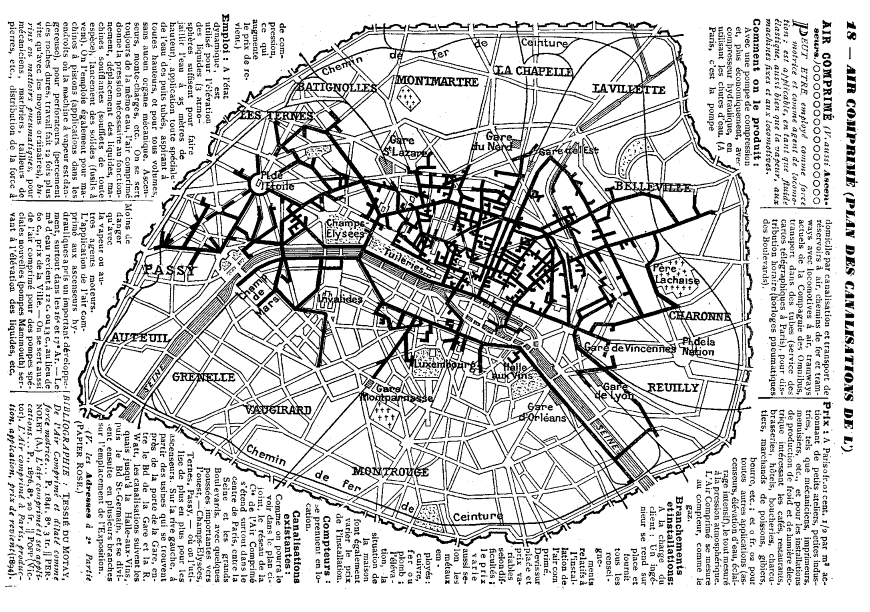

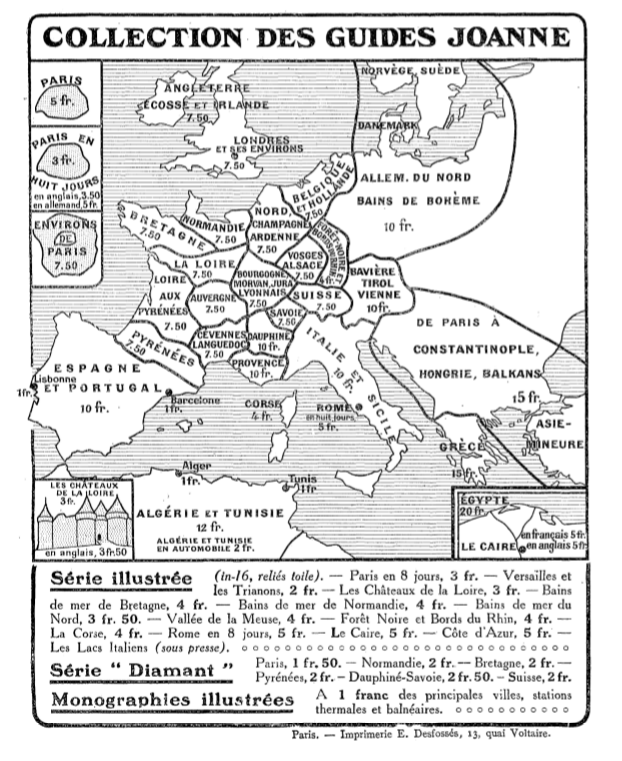

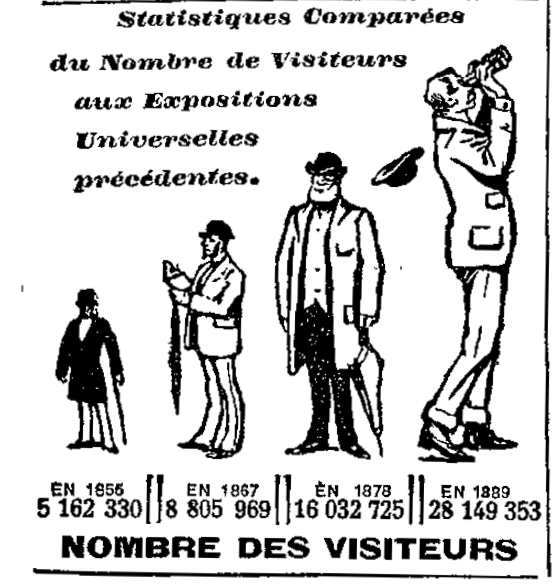

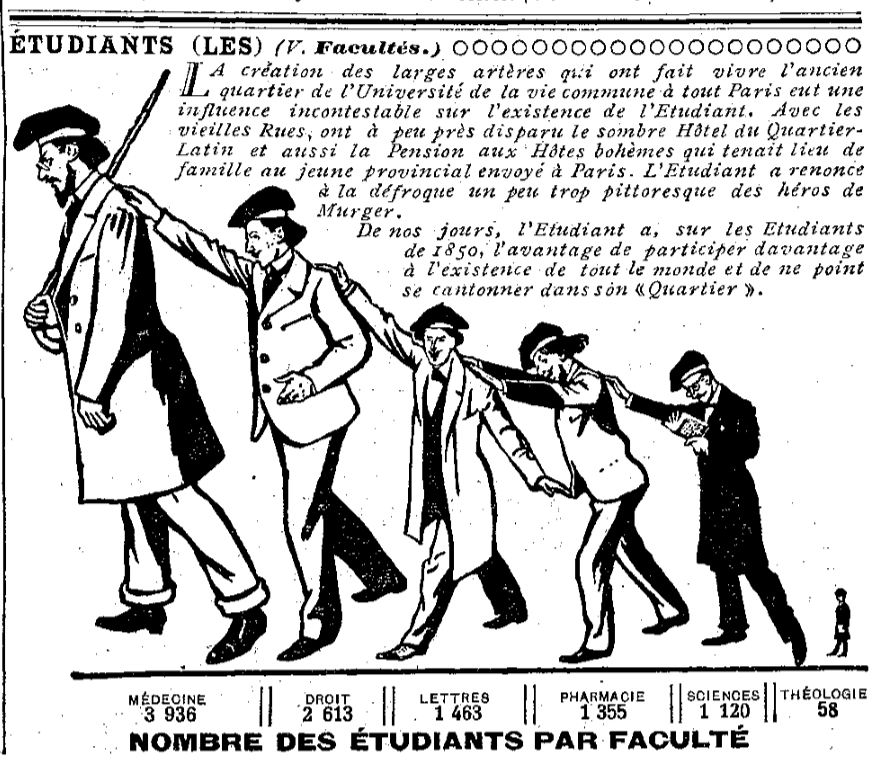

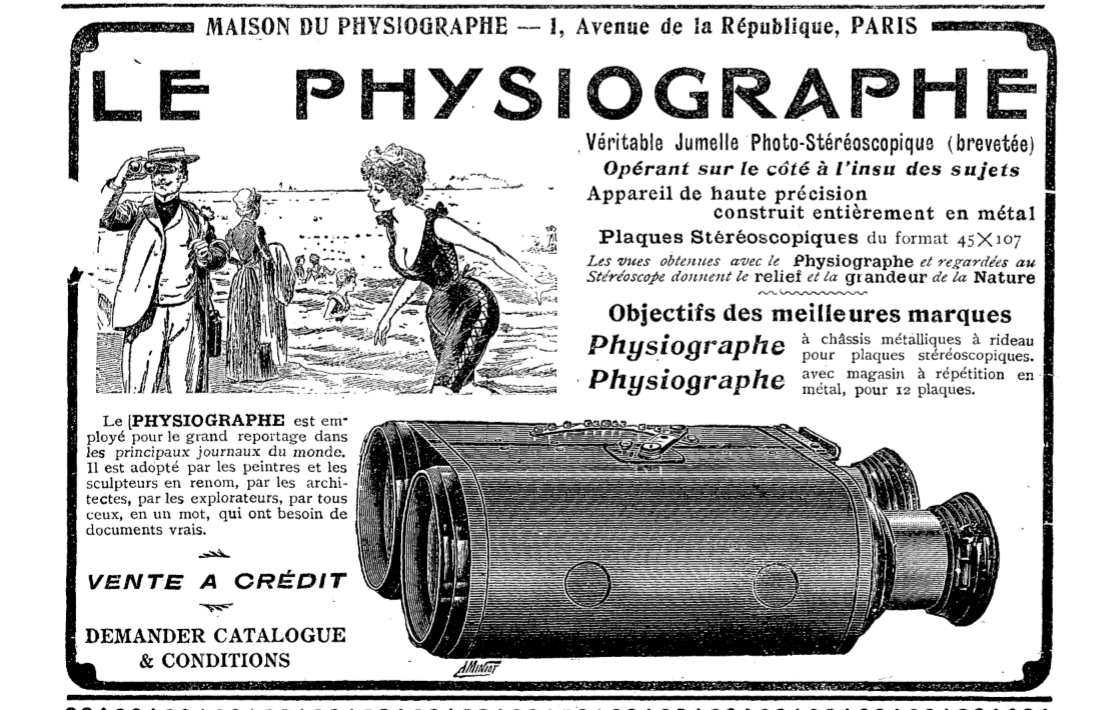

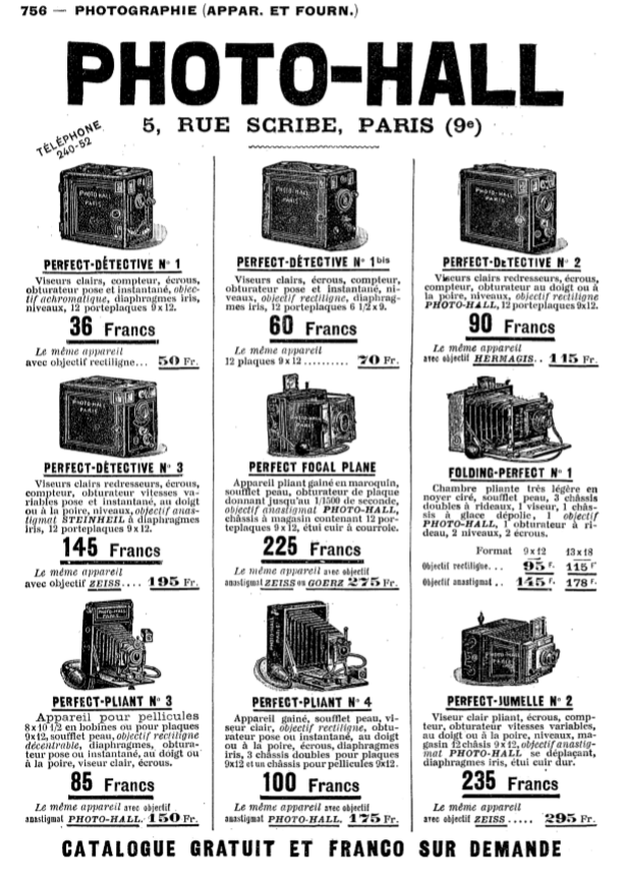

This striking image appears as the frontispiece of the 1910 Paris-Hachette directory. In earlier editions the total of addresses listed is not as high. So struck was I by this graphic that I went through the directories to see what other maps turn up. None is as powerful as the above, but I did like this 1900 diagrammatic breakdown of Paris according to space taken up by buildings, streets, gardens, canals and cemeteries: This 1904 breakdown of Paris into arrondissements and quartiers is more useful: But more beautiful is this aid to calculating the duration and cost of taxi journeys within the city, from the back of the 1913 Hachette directory: The map comes with an explanation of how to make these calculations, but I must confess that I haven't fully fathomed how it works: Here are some other maps that struck me: And here are a few non-cartographic images that caught my attention. This method of representing proportions was used repeatedly in the 1900 directory: I had never come across this type of camera before: I was particularly struck by the contrast between what the text claims (that this is an instrument used by journalists, painters, sculptors, architects and explorers) and what the image illustrates, that with this camera louche men can secretly take stereoscopic photographs of women in swimwear. I also made a note of these advertisements:

1 Comment

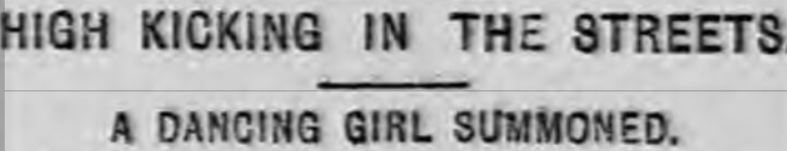

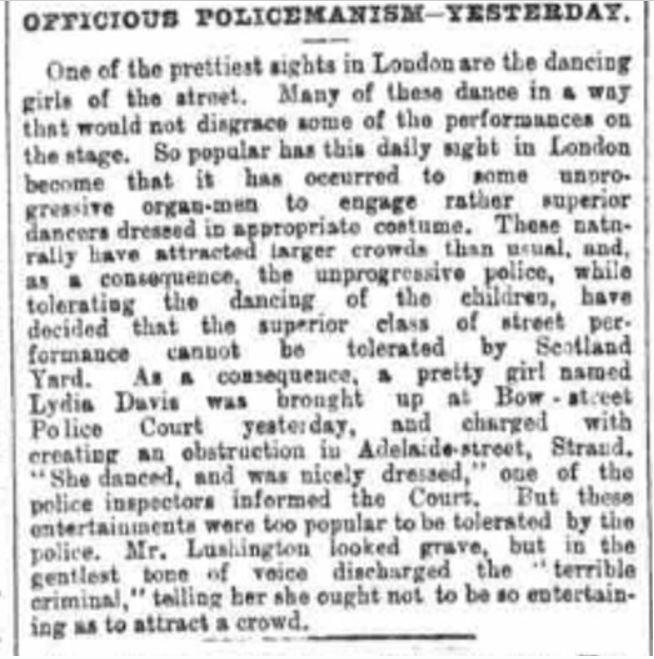

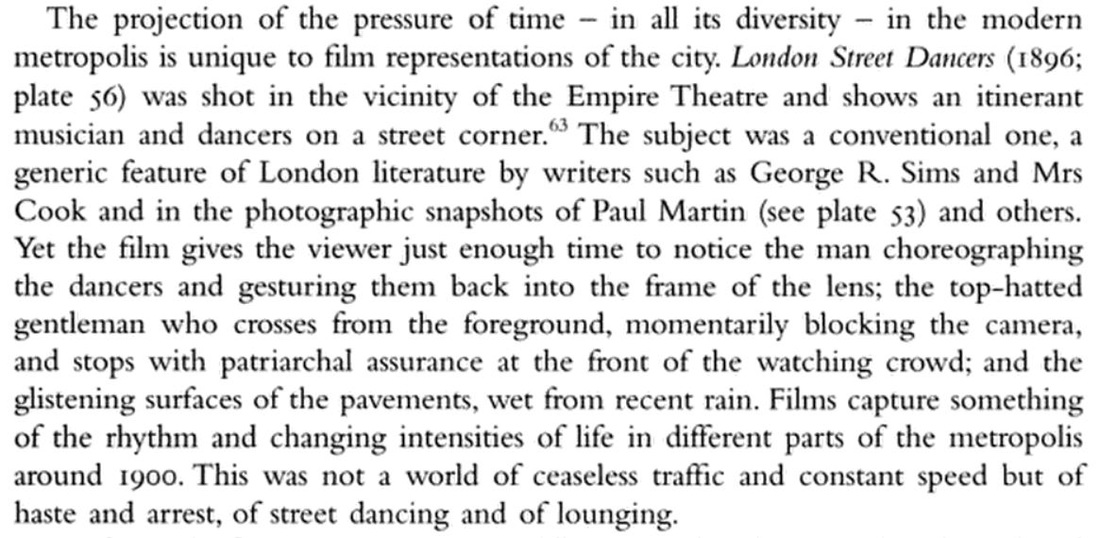

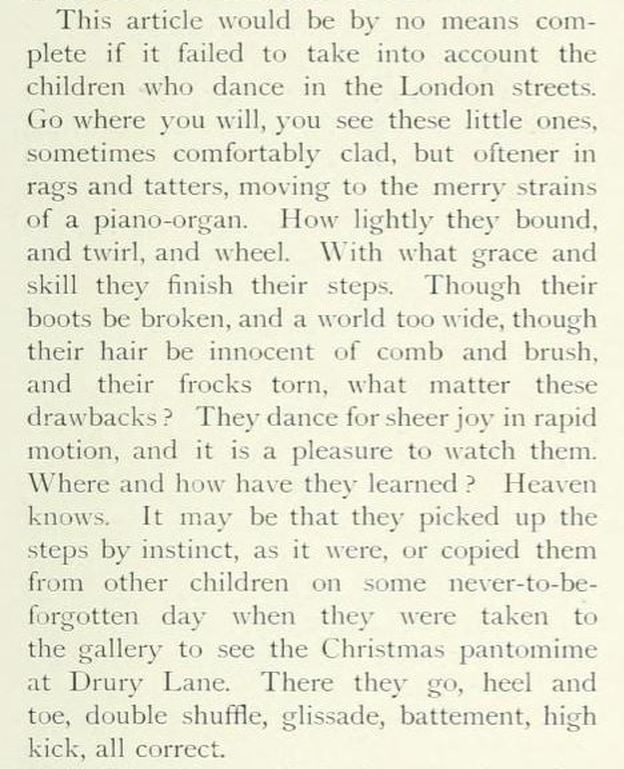

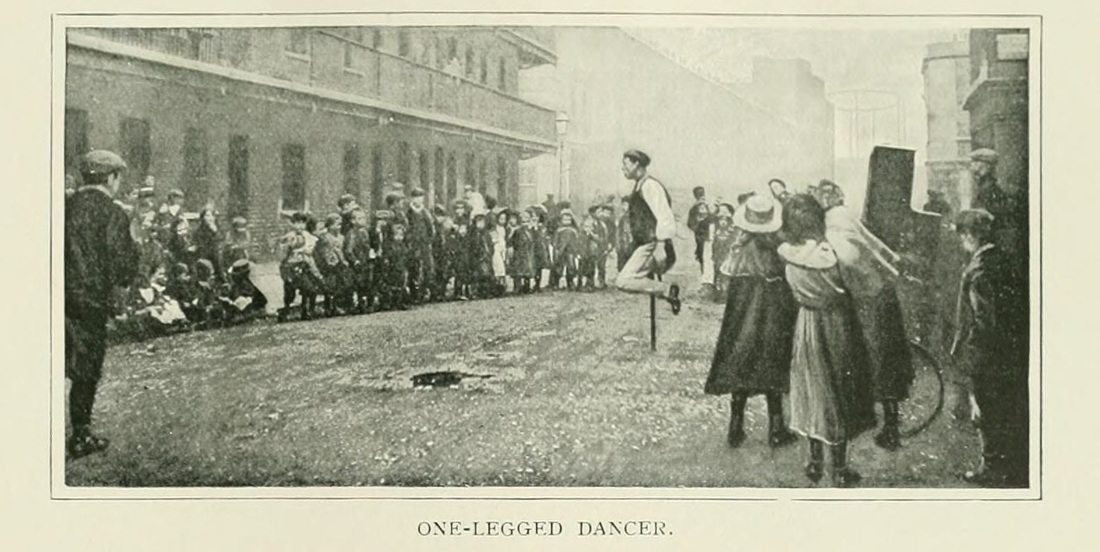

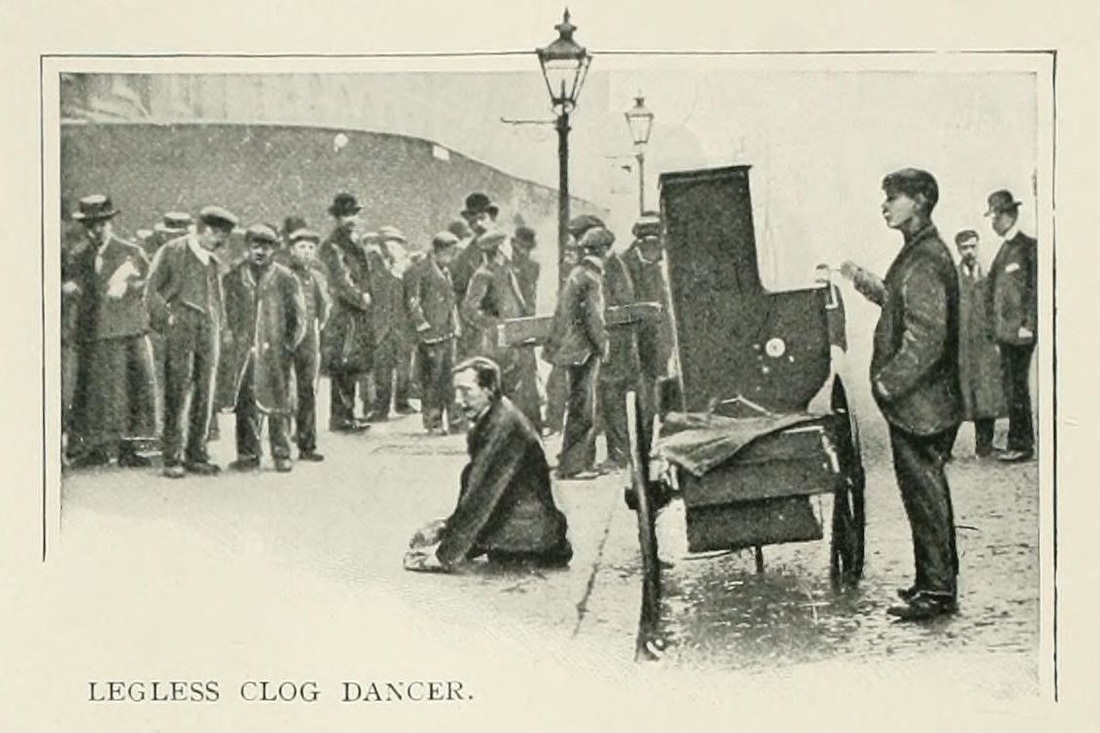

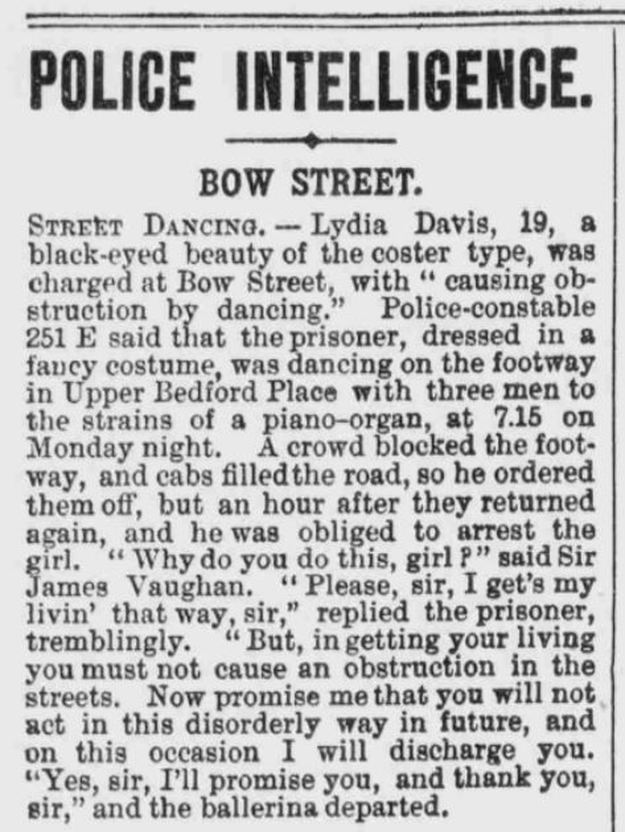

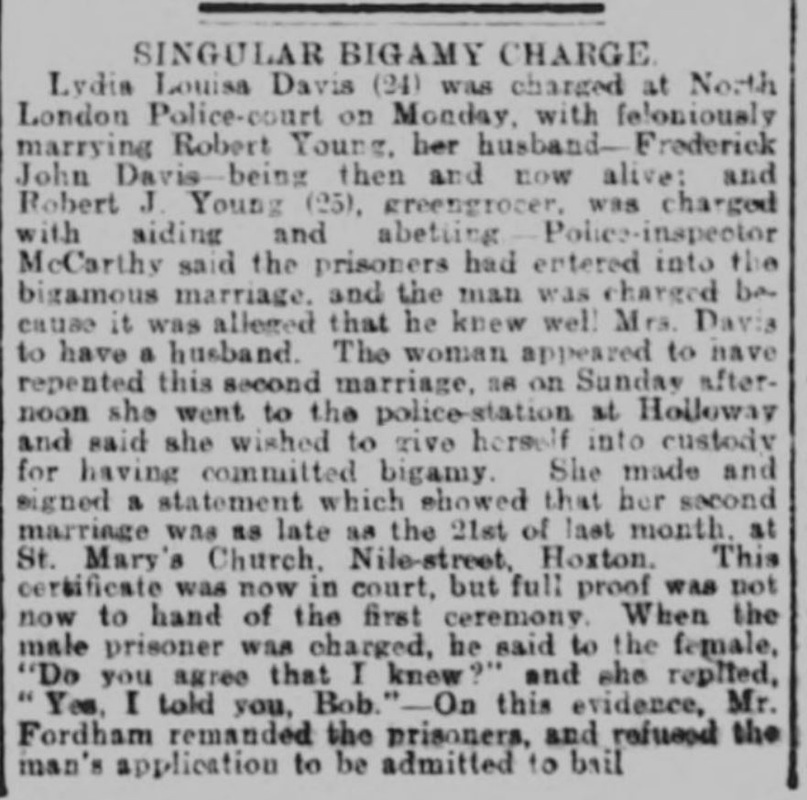

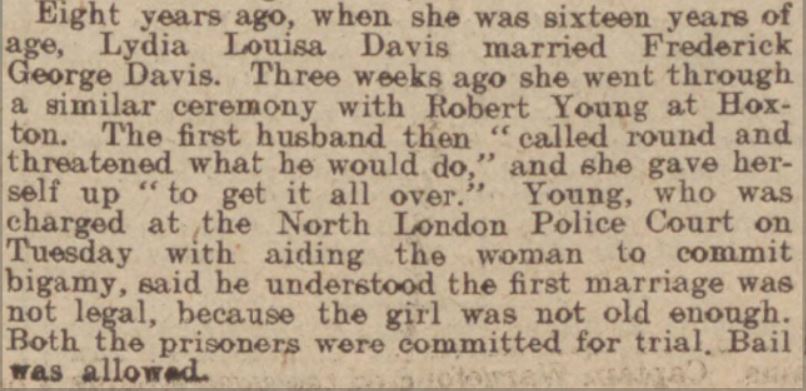

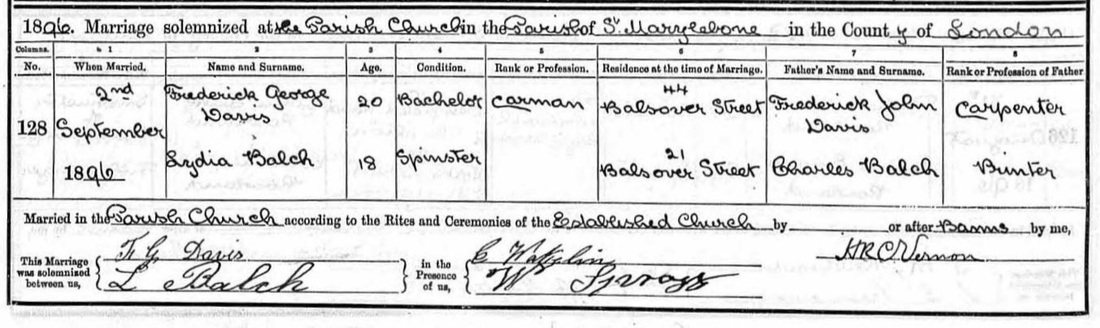

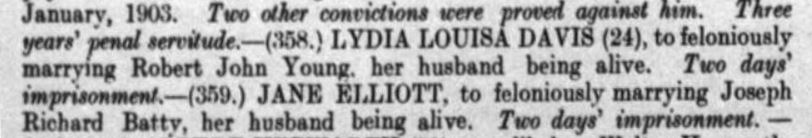

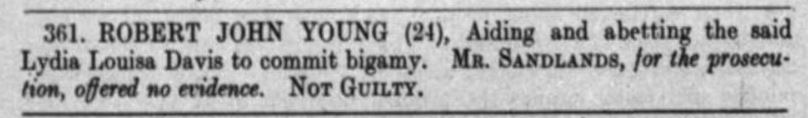

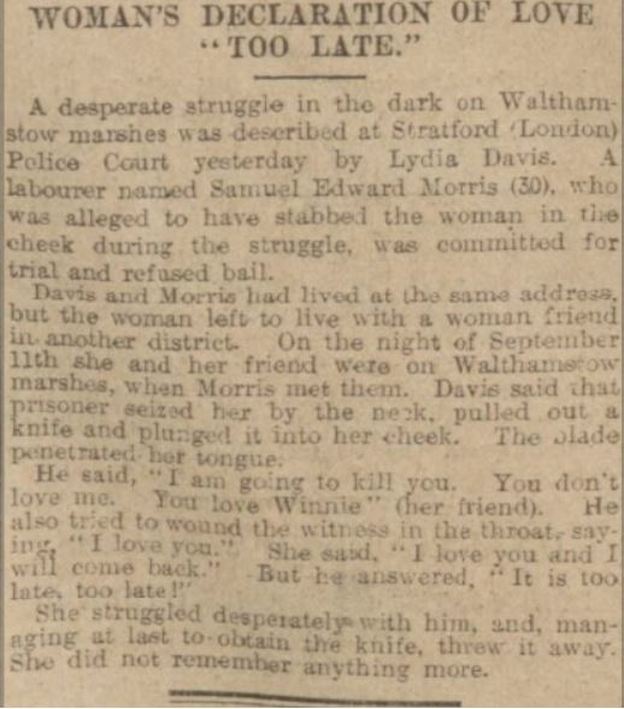

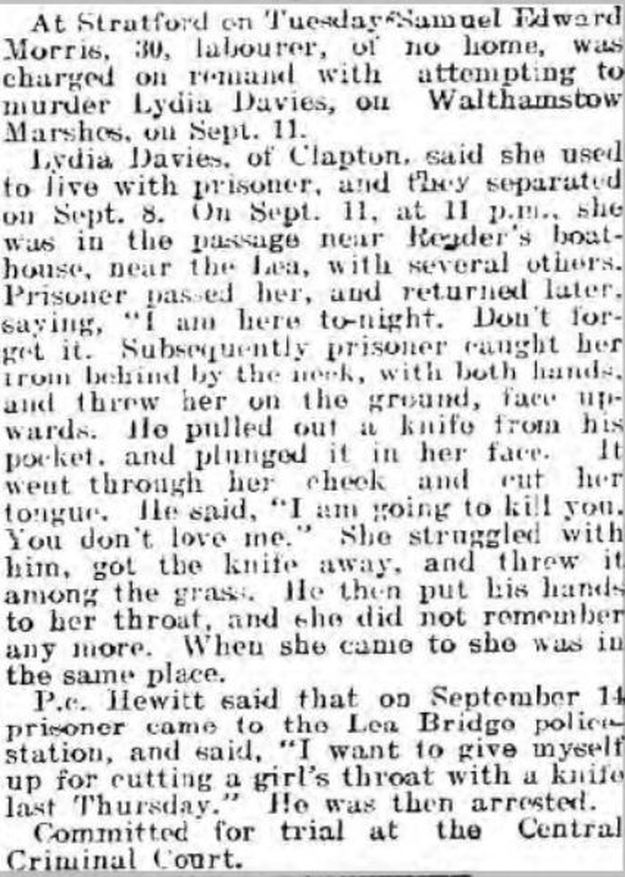

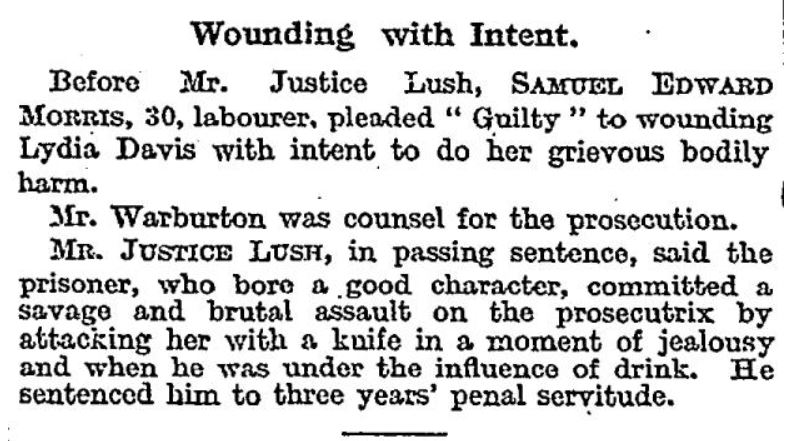

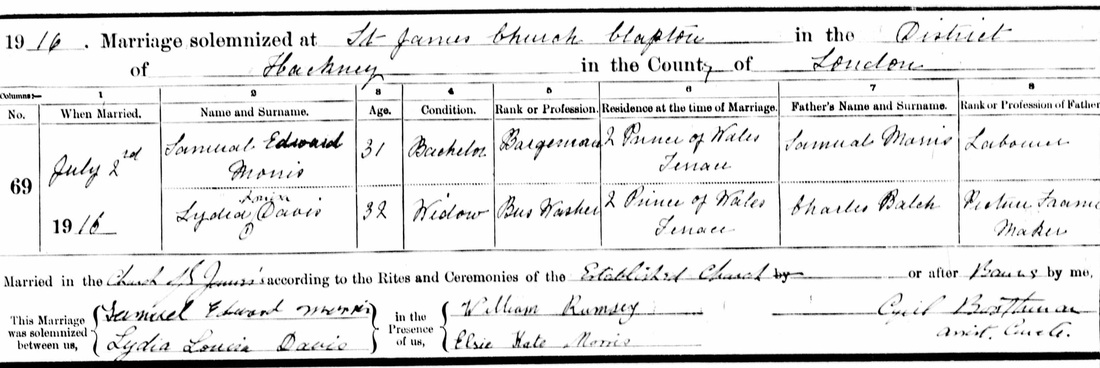

When the 1896 Lumière film Danseuses des rues was screened on French television in 1995, the accompanying commentary stated that the three women dancing were Irish. Other than that the actual dance looks like a hornpipe, I can't see on what this attribution of ethnicity is based. Similarly, the ethnicity attributed by this description of the film from the 1897 Warwick Trading Company catalogue seems to be based only on a prevailing cliché: 'Two little urchins are dancing to the airs of a grind organ, under the masterly manipulation of a dusky Italian, surrounded by an admiring crowd.' In search of better context for this film, I came across contemporary newspaper reports of a young woman arrested for dancing on Adelaide Street, by the Strand (not far from where the film was apparently shot, on Drury Lane): I'm not suggesting that the woman we see in the Lumière film is Lydia Davis, nor indeed that her accompanying barrel organist is the unfeasibly named Ernest Edifit: But Lydia Davis and the performers in the Lumière film belong together as a type of London street life in the 1890s for which illustrations are rare. The best I have found is Spencer Gore's sketch from 1904: In her book The Haunted Gallery, Lynda Nead gives a context to the Lumière film: This may be a world of street-dancing and lounging, but the only ones likely to dance in Paul Martin's photograph are the children. Only children are dancing in the illustrations below, by Dorothy Tennant for her book London Street Arabs (1890) and by William Rainey in George R. Sims's Living London (1902): Likewise in this photograph, illustrating the article on dancing in Living London: In Sims's encyclopedia of London life there is a place for such 'rare spectacles' as the one-legged dancer and 'the man without legs clog-dancing': But there doesn't seem to be any account of professional street dancers like Lydia Davis and the women in the Lumière film. Emily Cook, in Highways and Byways of London (1902), while still sentimentalising over dancing children, does suggest that they may be being paid: (Dobson's 1876 poem 'Cupid's Alley', like Yeats' 1889 'Street Dancers', is about non-professional London street dancers.) The professional aspect of London street dancing is clarified in this 1896 interview with an organ grinder: The foreigner who made the remark that English people take their pleasures sadly had evidently never witnessed a group of ragged and unkempt London street girls merrily ‘footing it’ to the strains of a barrel-organ. A close observer must, however, be struck with the singular fact that at each of the ‘pitches’ in any one neighbourhood where dancing is indulged in, the same three or four girls can always be seen taking part in the recreation and following at some distance behind the organ when the latter journeys on to a fresh stand. ‘Oh! Yes, that’s easily explained,’ said an organ-grinder when questioned on the subject, ‘the girls are, in fact, part of the show, and share to some extent in the takings. Directly we begin to play they start dancing. Soon other girls follow, and a large crowd quickly collects, and our takings are then, of course, much greater. Why, at a single “pitch” in the North of London one evening I counted over forty couples of girls dancing – at half-past eleven, too – while there must have been some hundreds of people watching. Yes, that was a good night’s work, and altogether through our “decoys”, as they might be called. What do we give the girls who act as decoys?’ continued the organ-grinder. ‘It is hard to say exactly – it depends upon what we receive from the crowd. We treat them fairly, and pay according to the takings. What classes of girls more than others seem to look forward to my coming every night? Well, I can hardly tell – little mites just able to toddle, as well as married women, are often waiting for me at corners of my round. The best time is about nine o’clock. Girls, too, who must have been hard at work all day, join in as heartily as any of the younger ones, and would dance all night if I kept on playing.’ People must often wonder how the children learn their steps, but it seems that in every neighbourhood two or three girls have taken part in a Christmas pantomime, and these not only practice the steps they were taught there, but teach their friends also. Again, mothers who have danced when they were younger show their children how they used to do it. Some really splendid dancers may often be seen amongst these children of the slums, many of whom go direct from the streets to the pantomime stage. There can be no doubt that the girls are all the healthier for their open-air amusement, which obliges them to leave for a time the narrow alleys in which they live, and to seek more open spaces in which to enjoy themselves thoroughly. Furthermore, one has only to watch the faces of the dancers to be convinced of the cheering effect produced by what may be reasonably considered a regular part of the life of the poorer classes in London. Cassell’s Saturday Journal, reproduced in the Northern Echo, 23.7.1896. That's about all I have found regarding these street dancers in general, though there is more in the newspapers about Lydia Davis in particular. Two years later she is once again arrested for street dancing: Though Lydia is here only 19 years old, when she should be 22, she has progressed to dancing en ensemble rather than solo. I have now been distracted from my general topic; the second part of this post is about moments in the life of Lydia Davis, a sensational tale of bigamy, attempted murder, repentance and reconciliation. I have found no record of further arrests for dancing, but there is more to be known of Lydia Davis's life if we jump forward six years. On Sunday April 10th 1904, a woman of that name went into Holloway police station to confess that she had entered into a bigamous marriage: A report in a Northampton newspaper explains why, after less than a month, Lydia repented her second marriage: Robert Young's defence that he thought Lydia's first marriage wasn't legal because she was sixteen doesn't seem to be a strong one, firstly because as far as I know she could legally marry at that age, and secondly because, at least according to the certificate, she was eighteen when she married: Lydia got two days imprisonment for the felonious marriage: Robert was acquitted: It seems conclusive to me that the Lydia Balch who married Frederick George Davis in 1896 is the Lydia Louisa Davis who bigamously married Robert Young in 1904. Less conclusive is my identification of the Lydia Davis who married in 1896 aged 18 with the Lydia Davis arrested for dancing in 1896 aged 20 and again in 1898, aged 19. The discrepancies of age don't matter so much - we shall see later that larger discrepancies come into account - but the fact is that the marriage of Lydia and Frederick took place in September 1896, so that if it was she who was arrested in May of that year and gave her name as Lydia Davis, technically she would still have been Lydia Balch. I hold, loosely, to the identification on the grounds that I can find in the records no other Lydia Davis in London at that time and of roughly that age. I am guessing that she was calling herself Lydia Davis pre-emptively, before the formalisation of her union with Frederick four months later. This is a guess built, I concede, on shaky presumptions. More certain is the identification of the Lydia who legally married Frederick Davis in 1896 and illegally married Robert Young in 1904 with a Lydia Davis who in 1913 was living conjugally with a certain Samuel Morris in Clapton. We know of this from sensational news reports of Morris's attempt to murder Lydia: This is a sensational story, but there is nothing direct in these and other reports to connect this Lydia Davis with the woman we know of from 1904 and 1896. The connection comes three years later, when Samuel Morris is released from prison and soon after marries the woman he attempted to murder in 1913: This record shows that the Lydia Louisa Davis who marries Samuel Edward Morris is the daughter of Charles Balch, and so is likely to be the same Lydia Louisa Balch, daughter of Charles, who married Frederick Davis in 1896. The record above states that Lydia is a widow; I have found no record of the death of Lydia's first legal husband. It also states that Lydia is 32, when she is probably closer to 38. It adds that she is now working as a bus washer. That's all I have found out so far about Lydia Louisa Davis.

I'd still like to make a stronger connection between the Lydia arrested for dancing on the Strand and the Lydia who twenty years later is reconciled with the man who tried to kill her on Walthamstow Marshes. And I'd also like to find out if the Lydia L. Morris who died in 1965 at Southend-on-Sea, aged 87, was by any chance Lydia Louisa Morris, formerly Davis, born - in 1878 - Balch. (To be continued...)

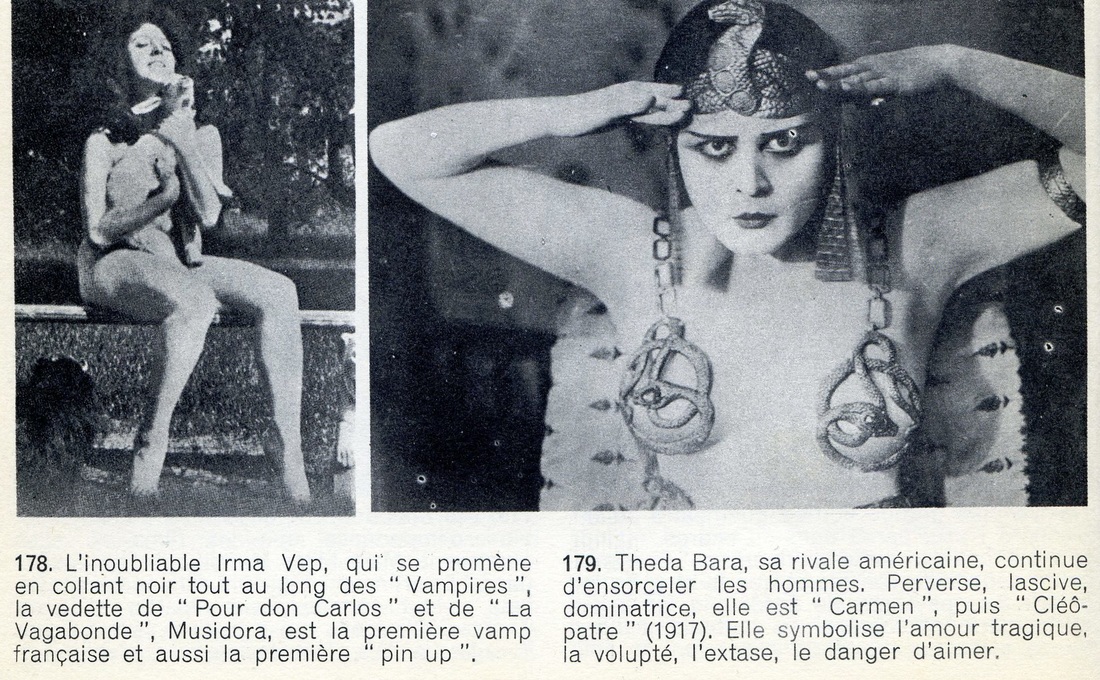

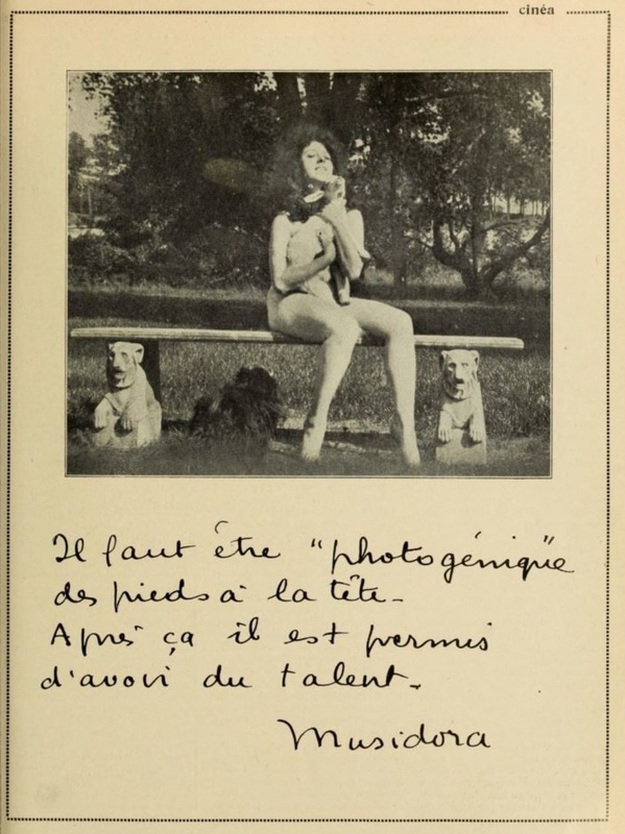

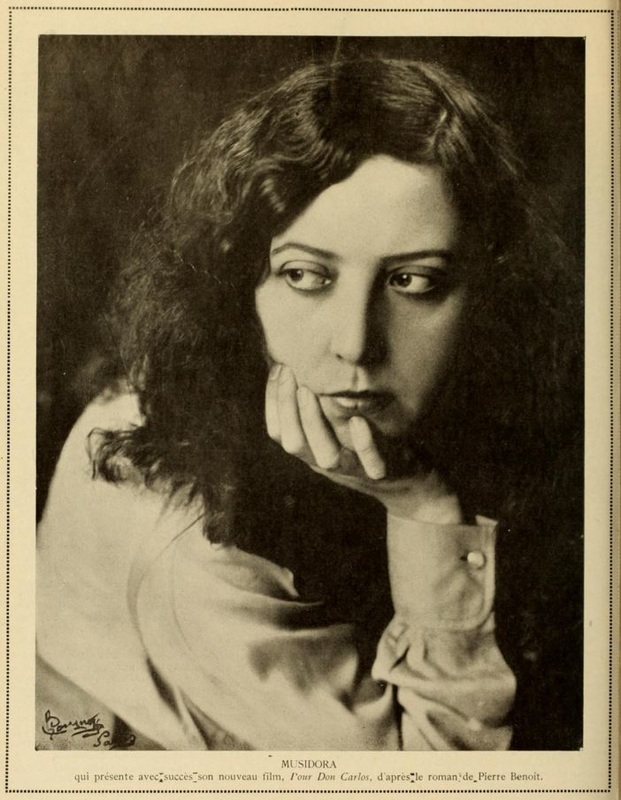

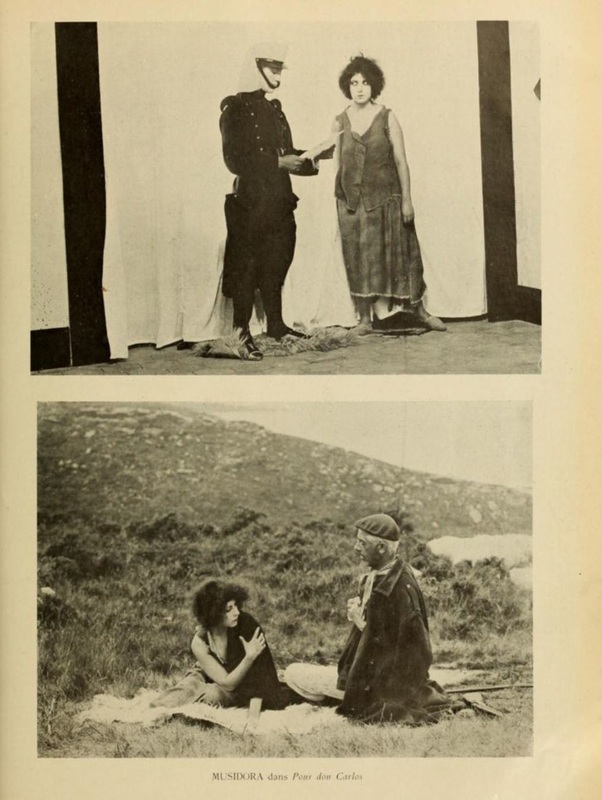

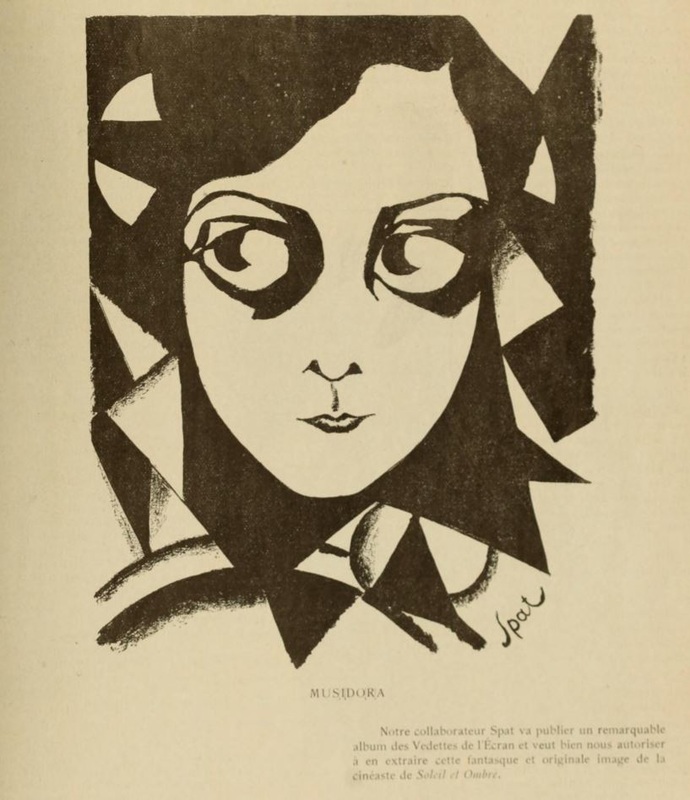

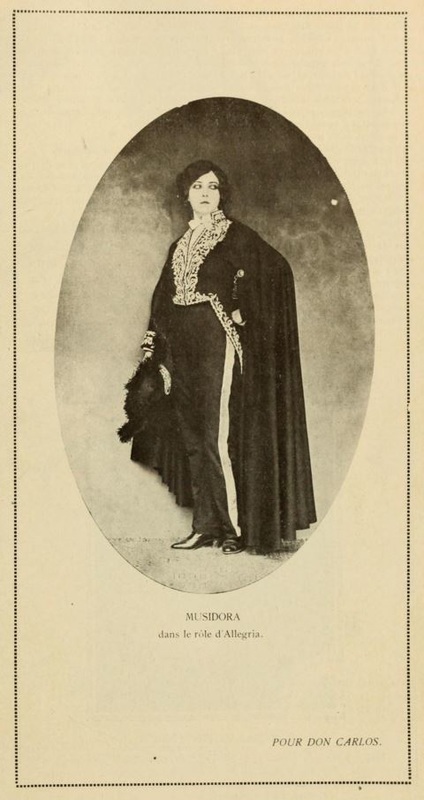

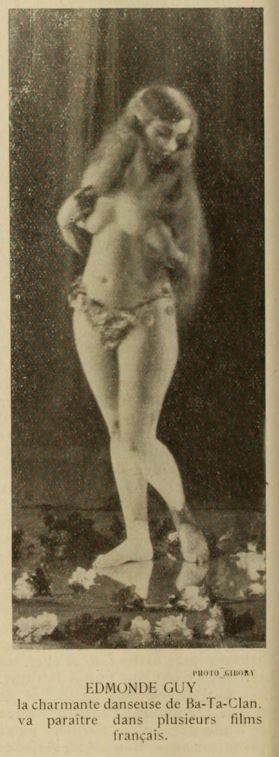

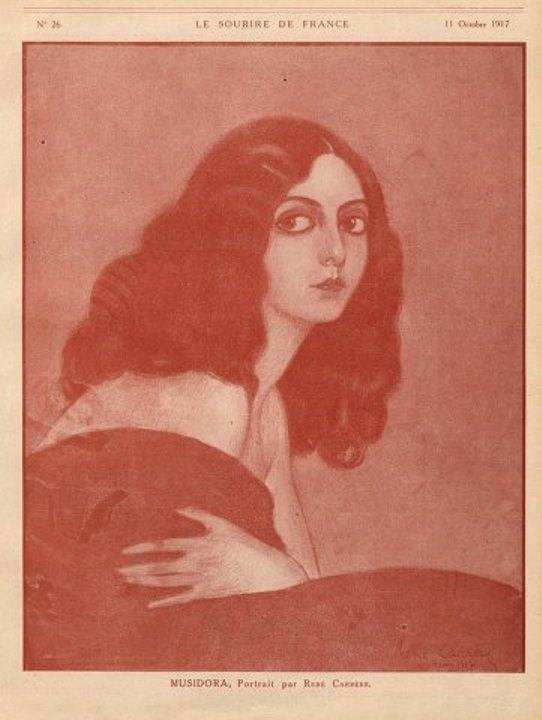

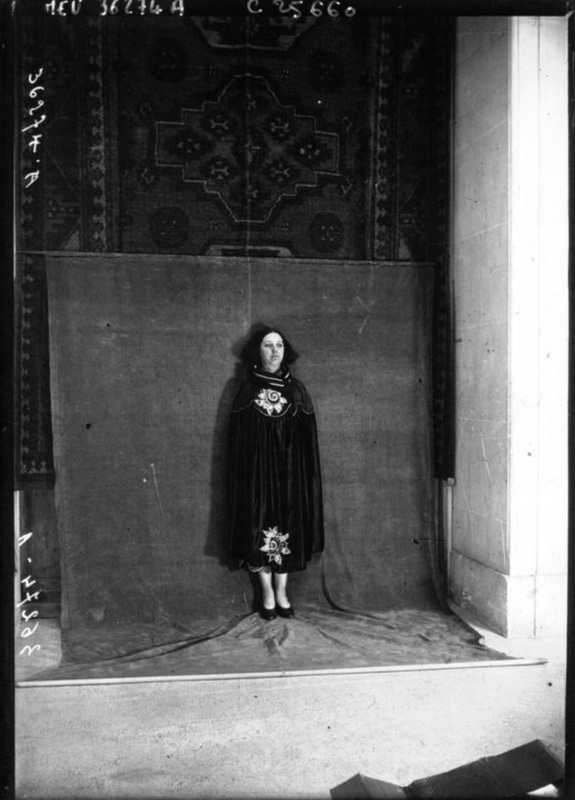

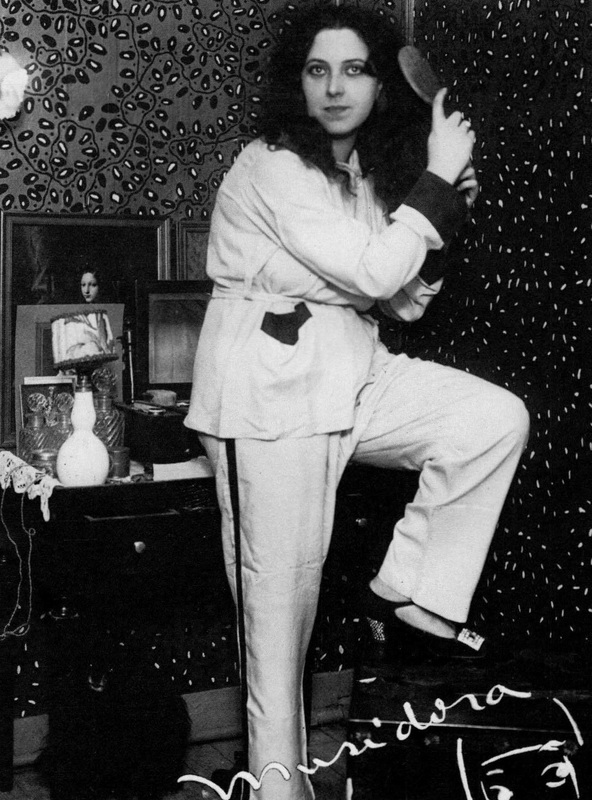

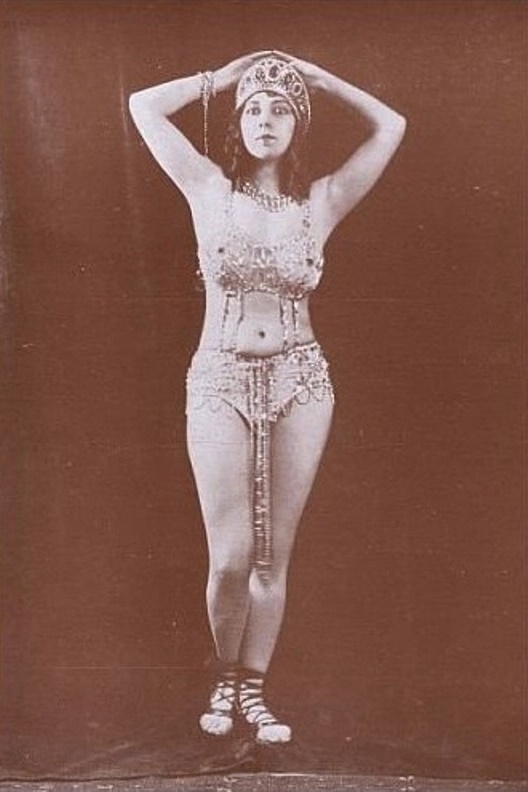

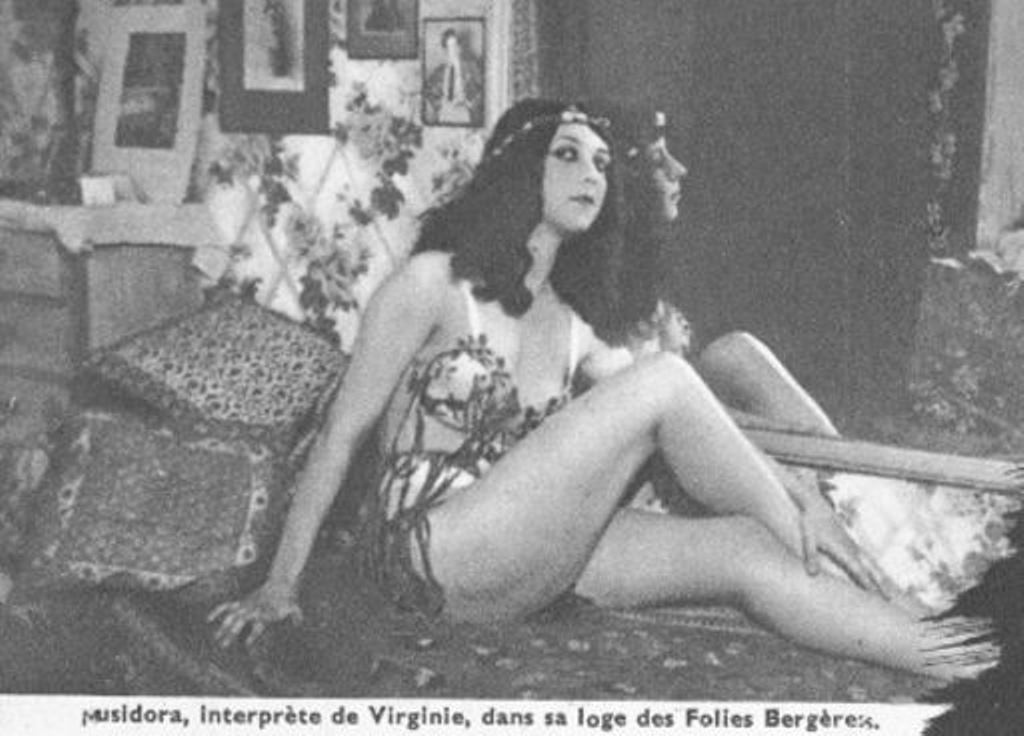

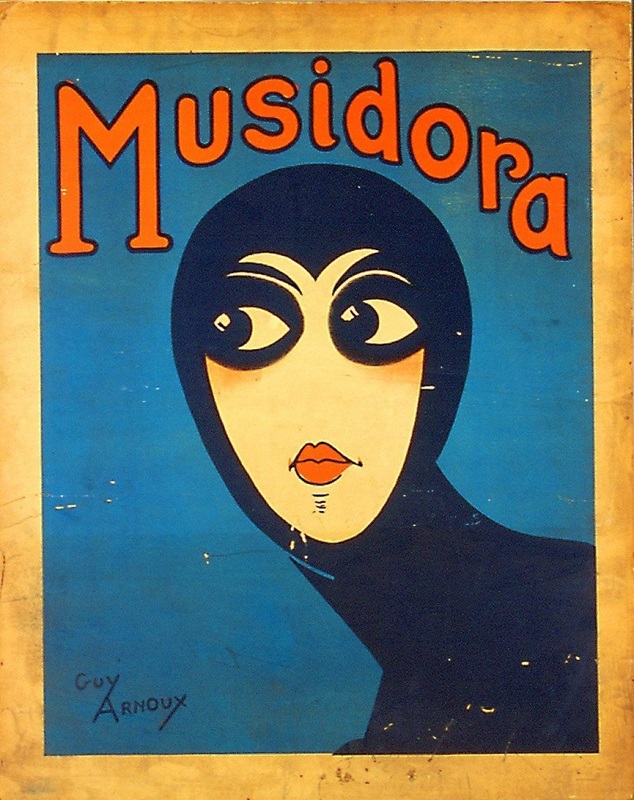

I know her, of course, as the 'unforgettable Irma Vep', even if Bessy's memory of her wearing the famous black silk outfit throughout Les Vampires is faulty. She only wears it in episodes five and six: In the course of Les Vampires Musidora wears - if I have counted correctly - thirty-two different ensembles, only seven of which are disguises: At no point in Les Vampires is she naked. In Judex (1917) she does undress, but only down to a swimsuit: Counting the swimsuit, her outfits in Judex total 21: Not enough of Musidora's films survive for a trawl of them to uncover the source of the image with which this post began, but a chance browse through the pages of Louis Delluc's journal Cinéa has obviated that need. This is from the issue dated August 10 1921: The page is presented without context, but this is clearly not from any film. Musidora's hand-written comment reads: 'You must be photogenic from feet to head. Then you are allowed to have talent.' The context of her remark is the journal as a whole, for which photogénie is the guiding philosophy, be it through the theoretical writings of Jean Epstein or competitions to find the most photogenic reader. 'Le Sens 1 bis', an essay from July 1921, gives the tenor of Epstein's views:

For the first time, the image-capturing apparatus presents a subjectivism and a subjectivisation that are mechanical, automatic, inorganic, neither living nor dead, controlled by the camera-crank, outside of man.

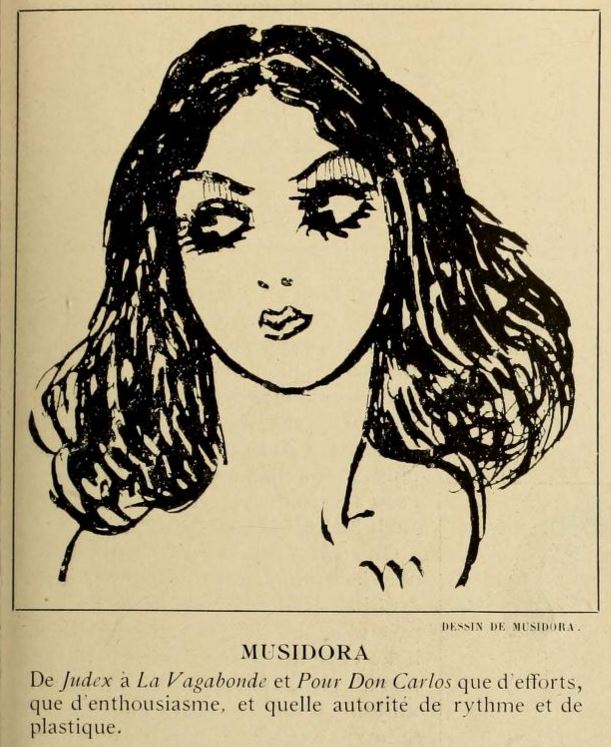

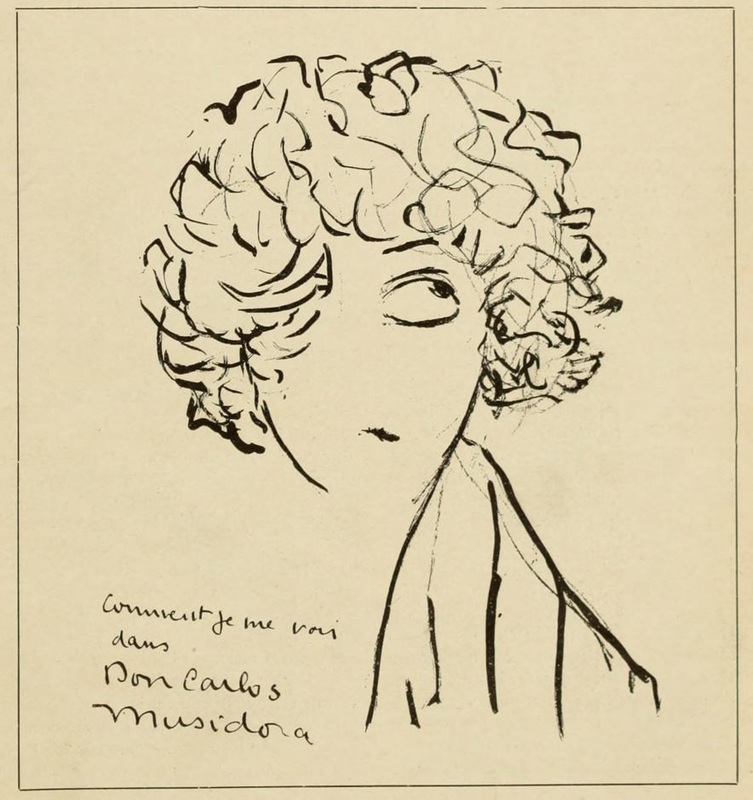

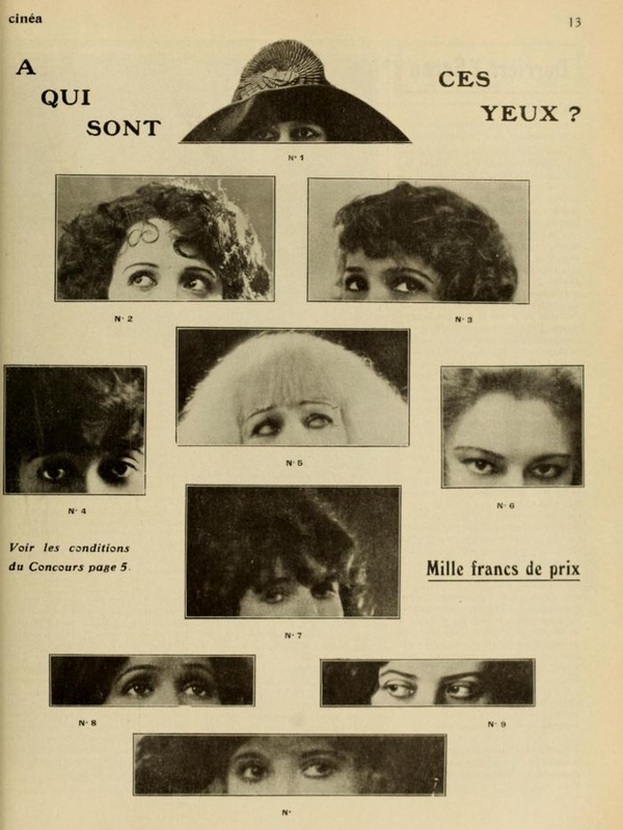

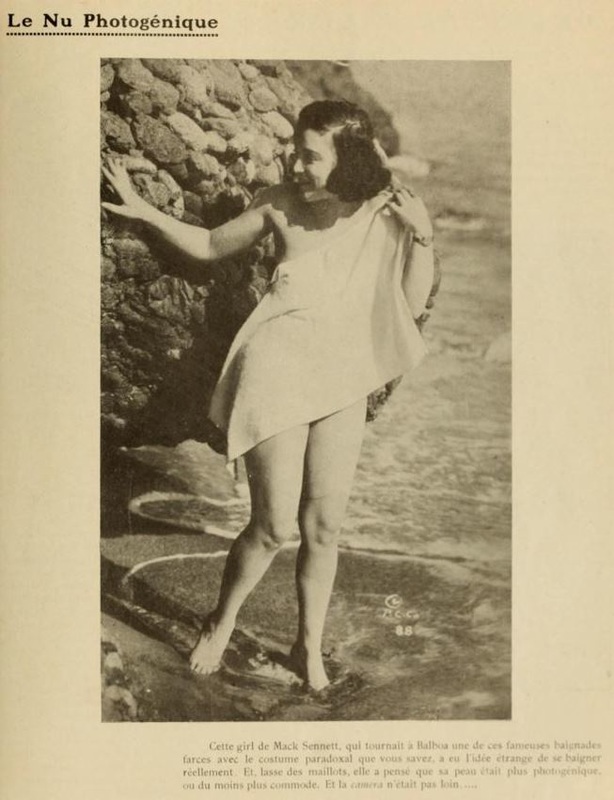

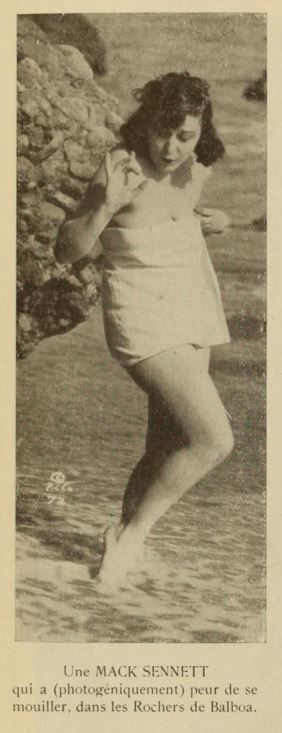

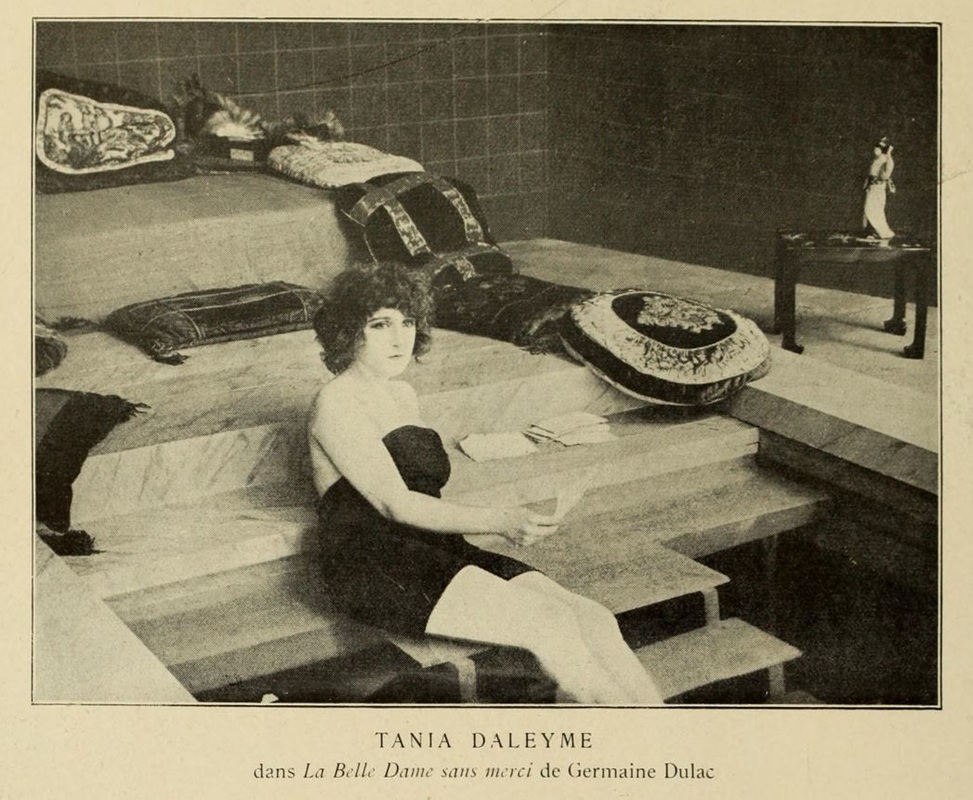

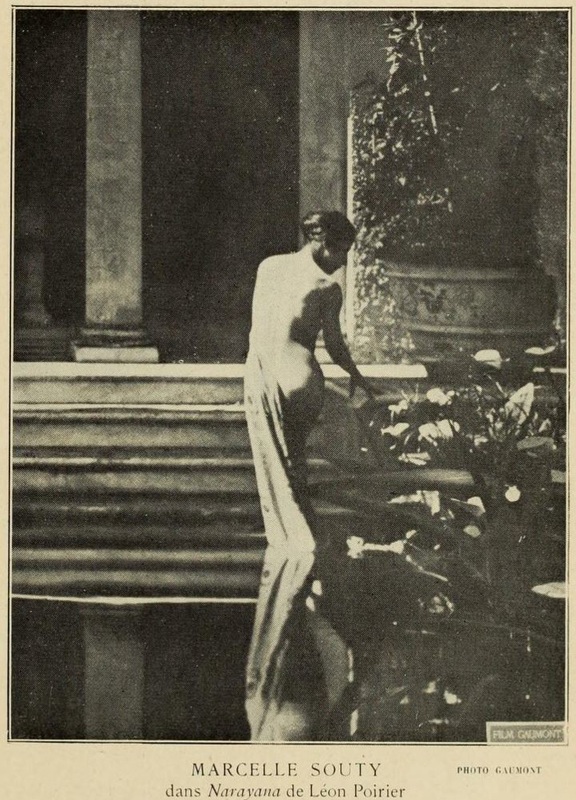

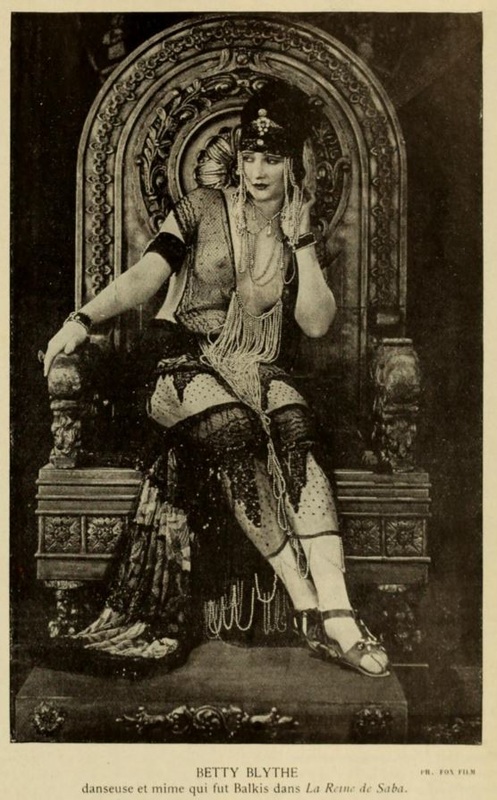

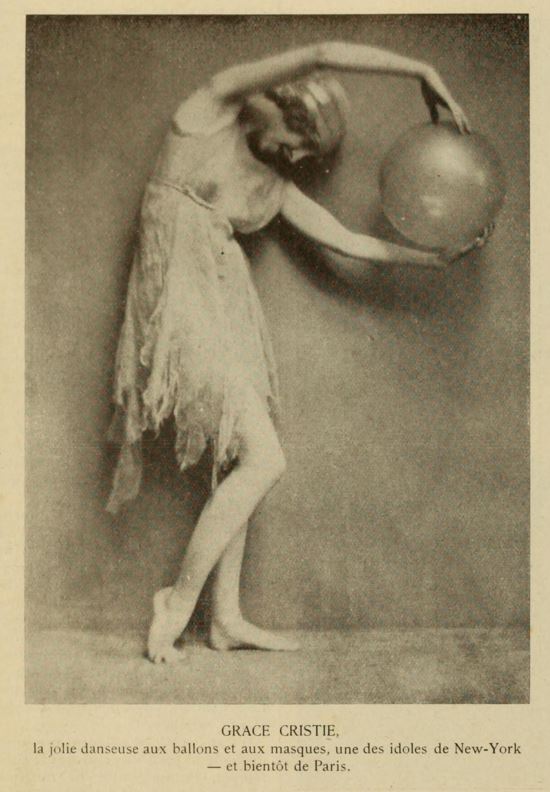

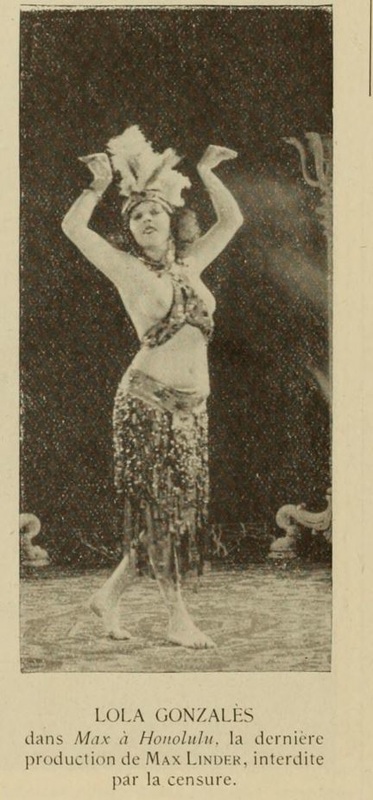

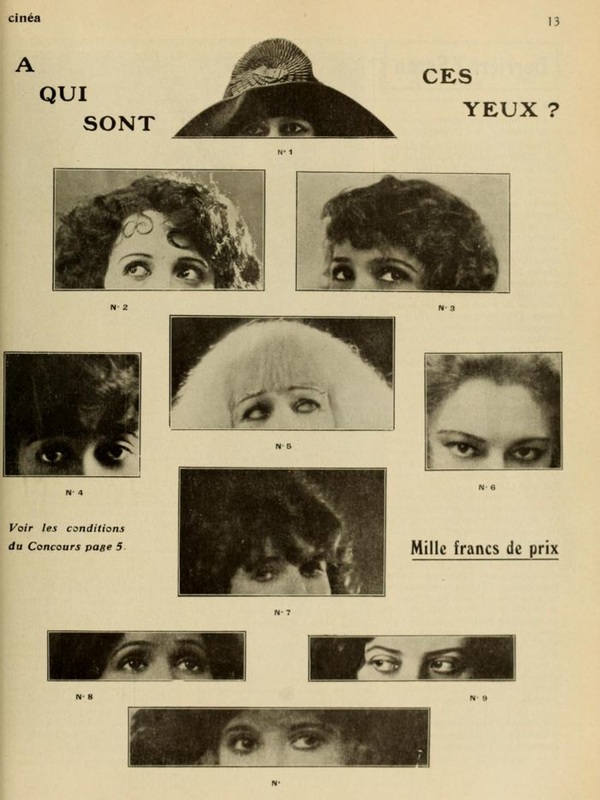

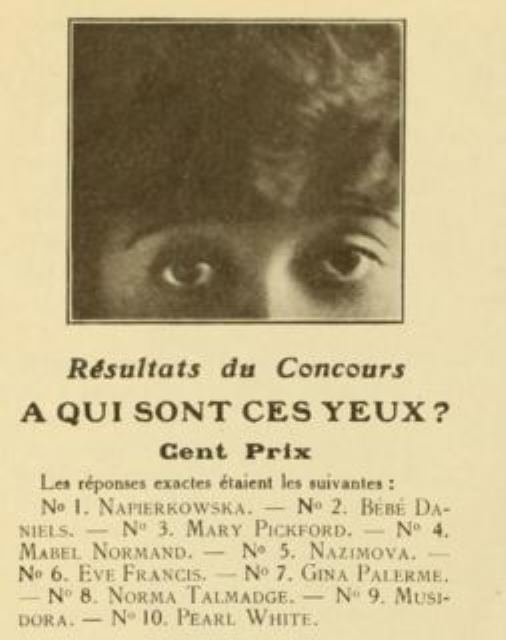

Musidora's 'photogénie first, talent after' comment reads like irony-tinged advice to would-be film stars. The nude photo is certainly not her only appearance in Cinéa. As well as photographic portraits and film stills there are caricatures, including two by her own hand: Musidora is also one of the answers in Cinéa's 'Whose Eyes Are These?' competition: (The answers are at the bottom of this post.) In Delluc's serialised novella 'Chagrine, demoiselle photogénique', the heroine refers to Musidora's photograph and quotes her comment: 'Musidora is photogenic from head to foot. I've seen her completely naked in a photograph but not at the theatre, and she hasn't invited me to her house' (Cinéa 94, 15.6.1923). The association of Musidora's nudity with photogénie matches a recurrent preoccupation in Cinéa. In an essay on Charlie Chaplin, Delluc writes of Mack Sennett that he has, 'consciously or not, given some remarkable pointers for that chapter of photogénie that will one day be substantial: the nude in cinema' (Cinéa 9, 1.7.1921). In September 1922, under the heading 'le nu photogénique', Cinéa published a candid photograph of one of Mack Sennett's bathing beauties, caught having gone swimming without a costume. Earlier, in March, a different photograph from that same moment had illustrated an essay by Lionel Landry on 'le nu au cinéma': The year before, Landry had published a piece called 'Pour le nu photogénique', with these illustrations: These are the other illustrations for Landry's 'Le nu au cinéma': These and similar images in Cinéa give a kind of context to Musidora's nude photograph, but there seems to me a difference between these displays and Musidora's self-presentation of her photogenic nakedness. She has bypassed the conventional photogénie of the semi-naked beauties assembled in the pages of Cinéa. I think this is the only fully naked photograph, of anyone, in that magazine: Here, to close, are some other images of Musidora currently littering the internet: Here are the answers to the 'Whose Eyes Are These?' competition:

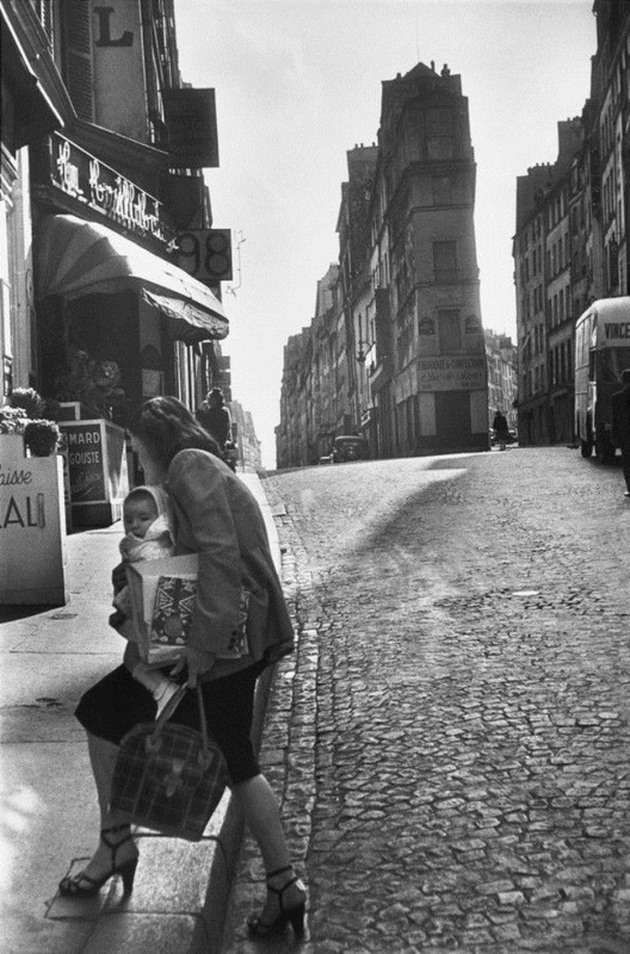

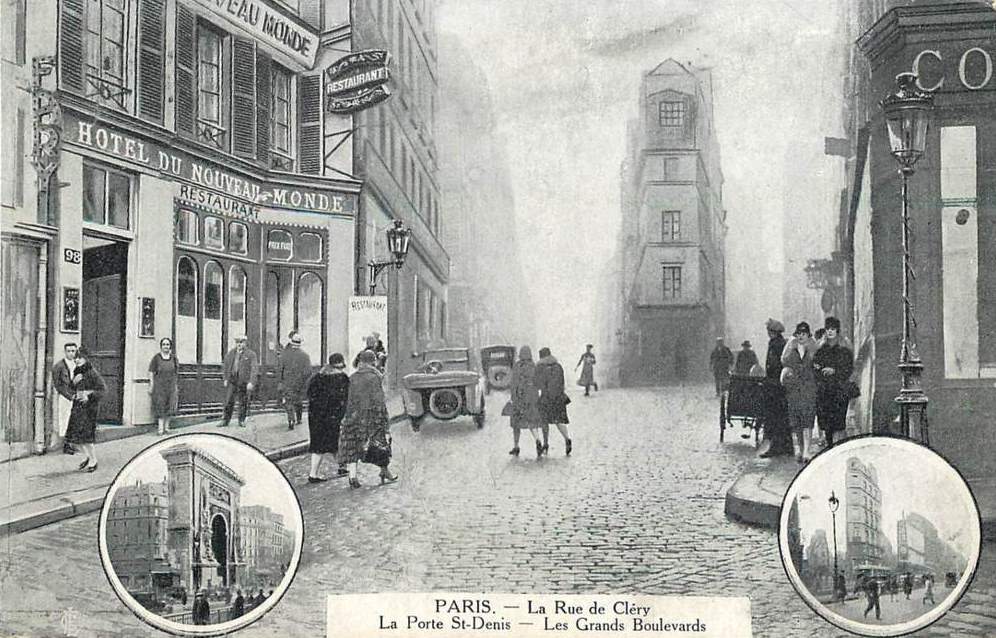

Atget photographed this junction at least twice: Atget's photographs are from 1907. Kertész's is from 1928. Roger Schall was here in 1935: Brassai came in 1939: And Cartier-Bresson in 1952: The only film I have found here, so far, is Jacques Baratier's New Wave parody Dragées au poivre (1963):

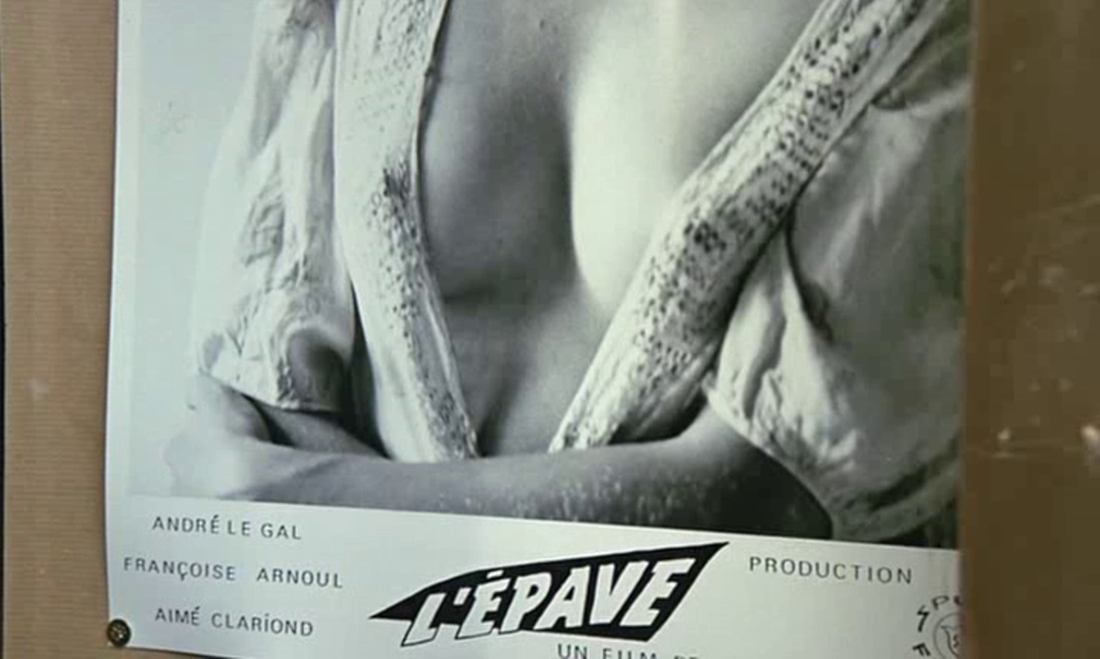

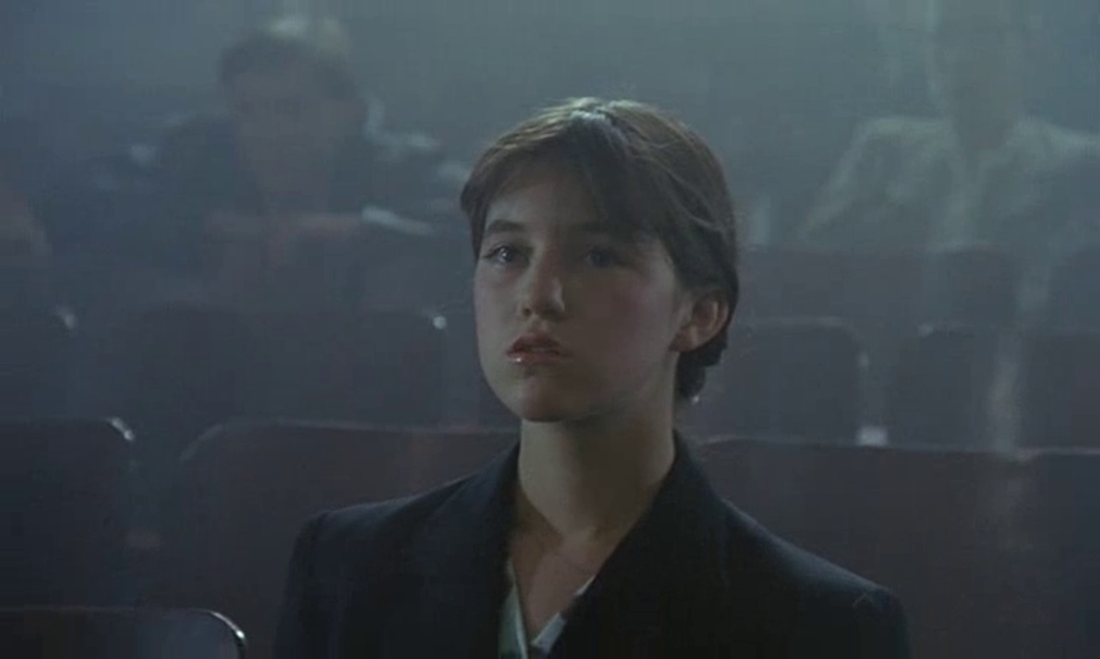

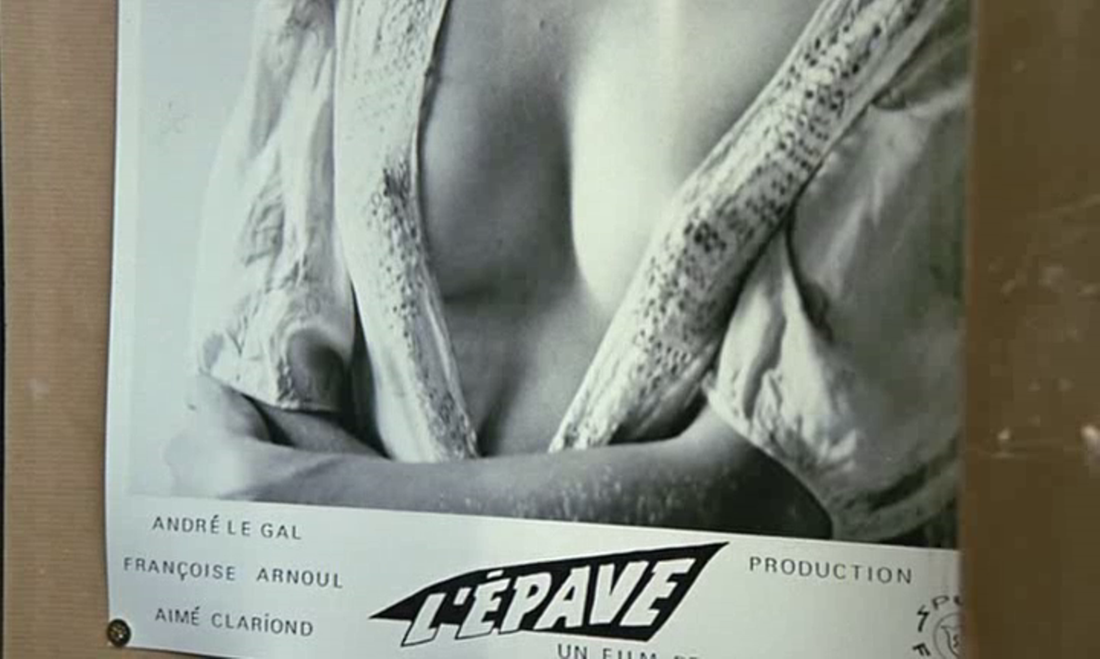

In Claude Miller's 1950-set film La Petite Voleuse, Janine (Charlotte Gainsbourg) compares her appearance to that of Françoise Arnoul, seen in a foyer-photograph for Willy Rozier's L'Epave, as she stands in the entrance to a cinema: Released in 1949, L'Epave fits the chronology of La Petite Voleuse, but other films referenced by Miller do not. In the entrance to the cinema is a poster for a forthcoming attraction: That La Petite Voleuse isn't troubled by anachronism is apparent when Janine goes to the cinema to watch a film called 'Passion Eternelle': We see nothing of the screen, and the dialogue and music are composed for Miller's film, rather than retrieved from the past. We know the title of the film she is watching from the poster in the foyer:

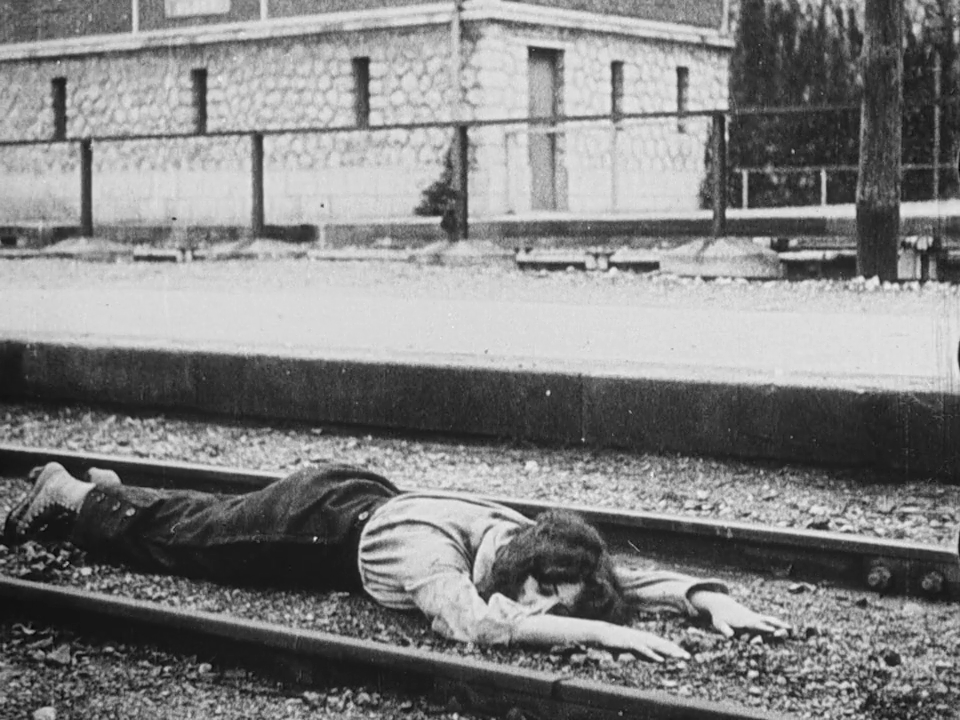

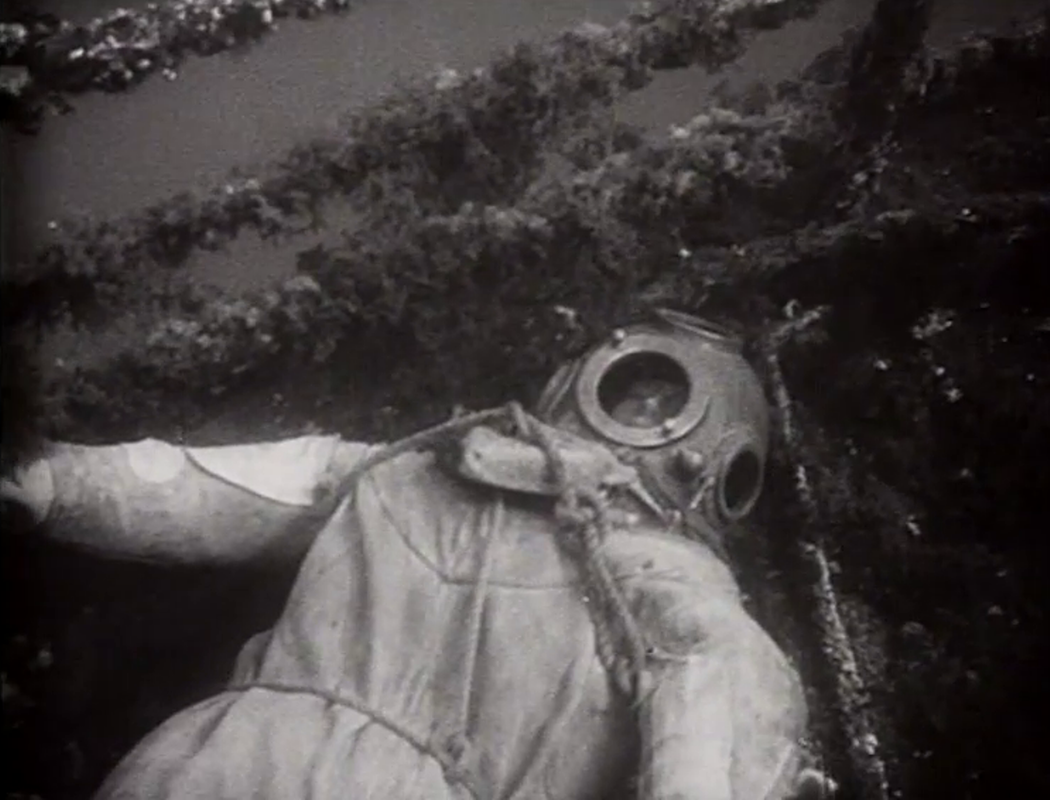

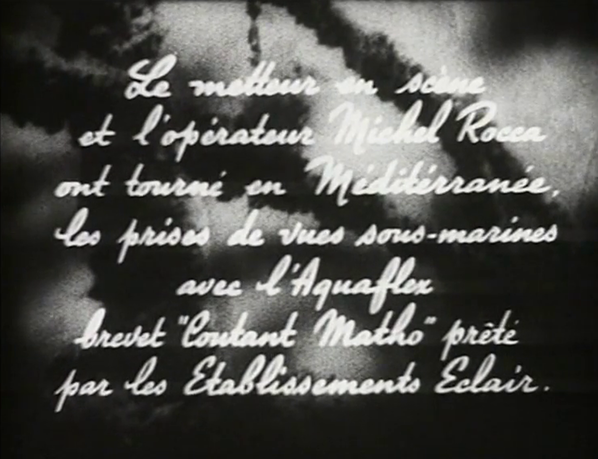

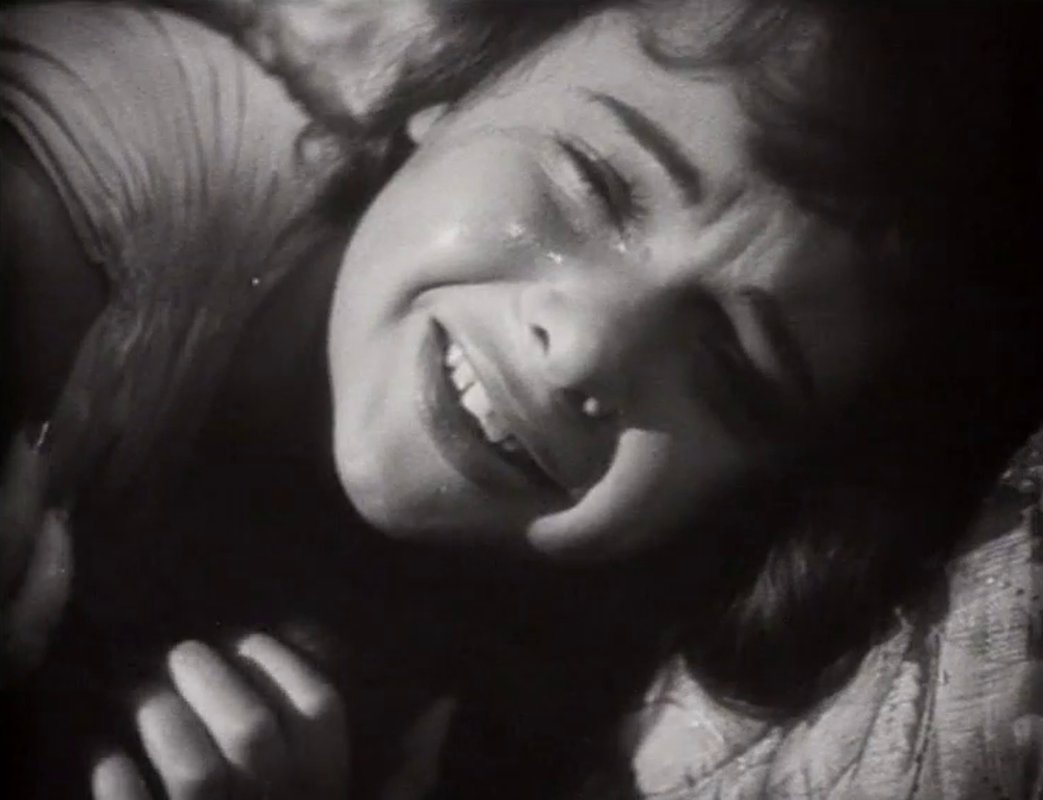

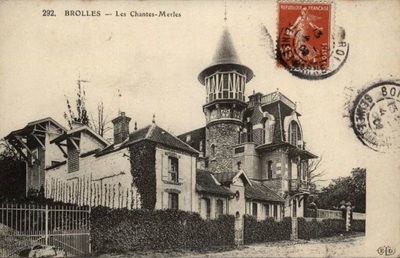

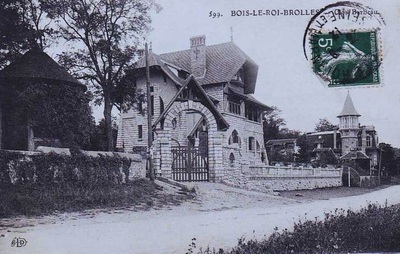

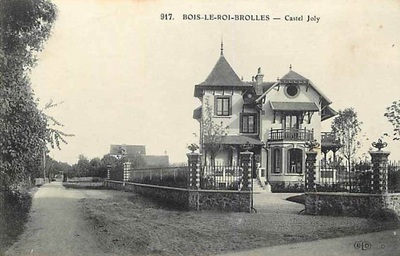

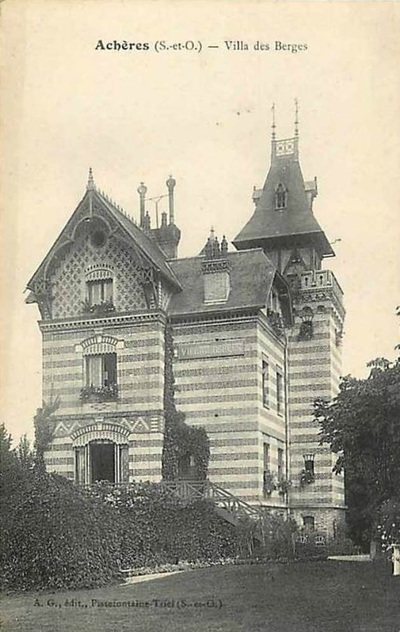

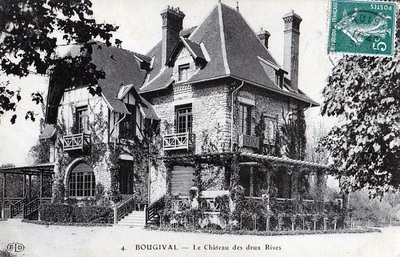

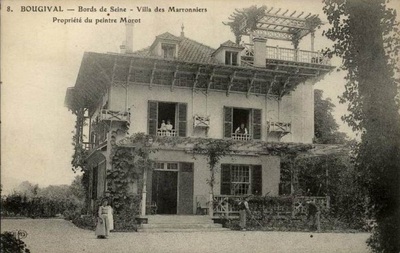

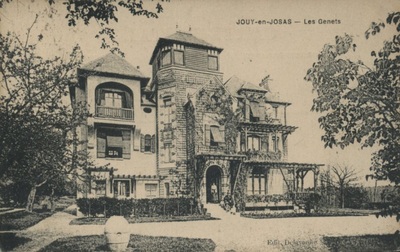

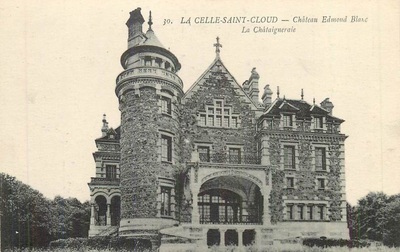

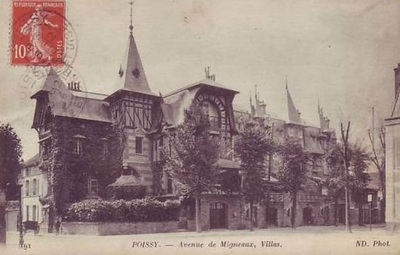

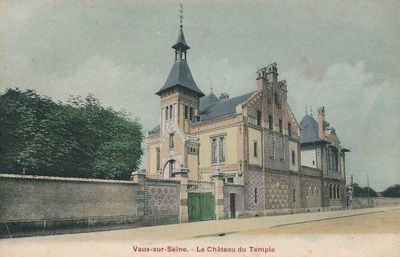

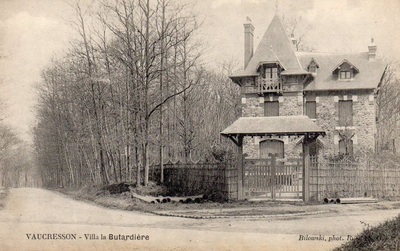

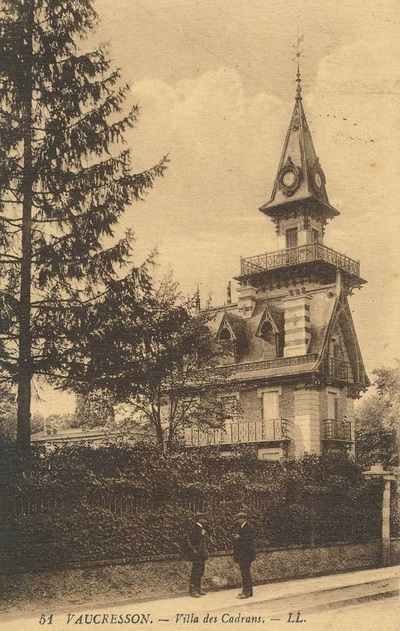

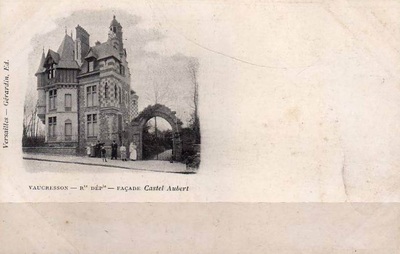

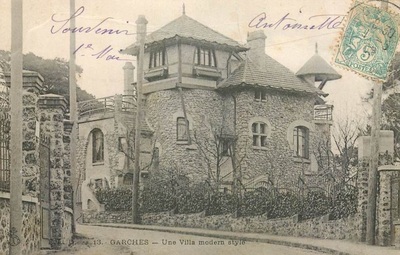

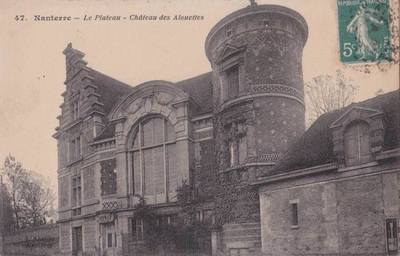

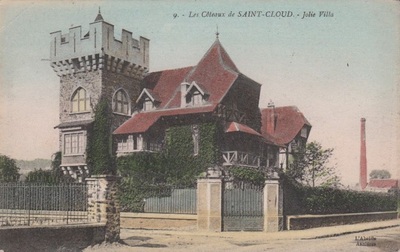

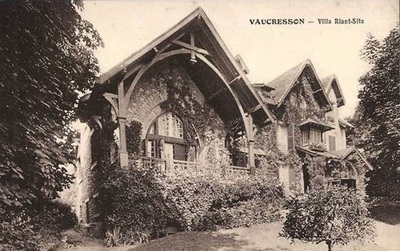

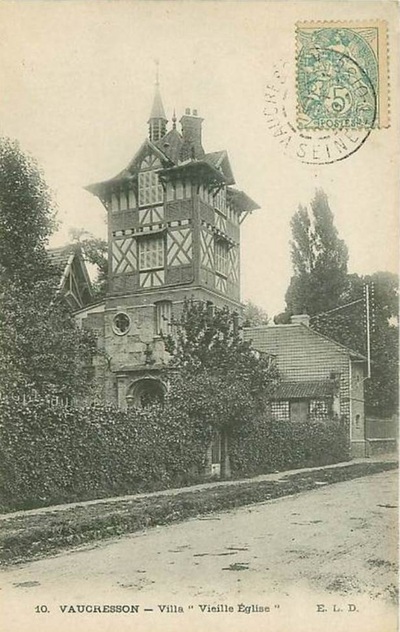

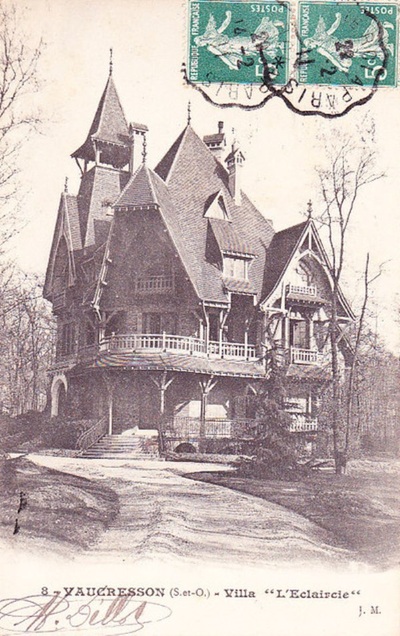

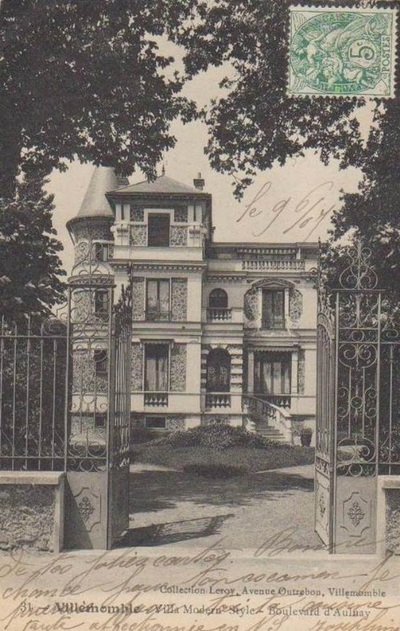

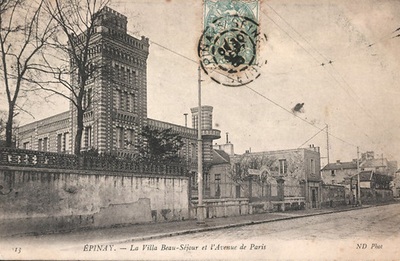

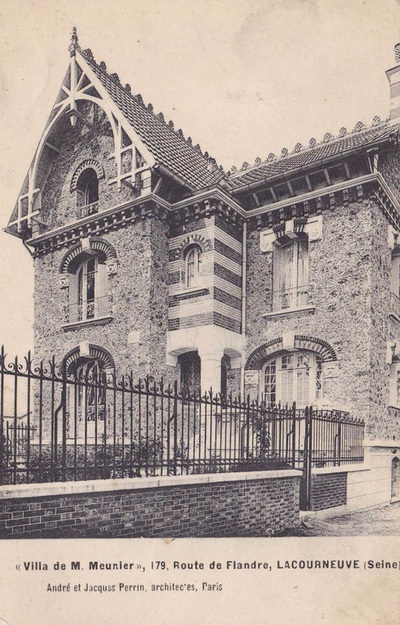

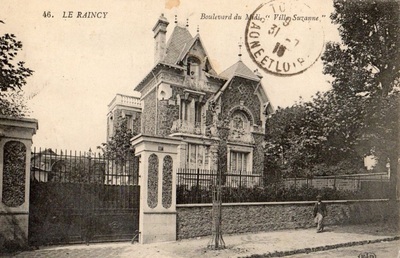

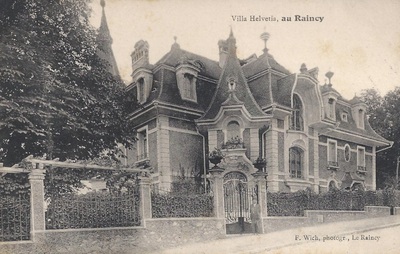

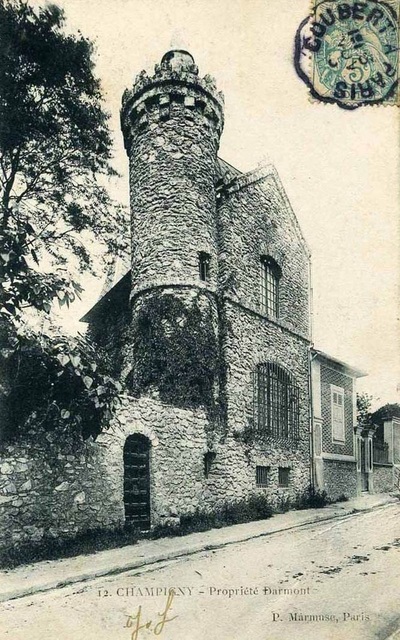

(For more information about the cine-references in La Petite Voleuse see the dedicated page at Cinéclap, here.) This discussion is just a preamble to what really interests me in this confluence of intertexts, which is Willy Rozier's 1949 film L'Epave, the only accurate period reference among the films mentioned in La Petite Voleuse. There are at least five aspects of the film that warrant attention. The use of voice-over is striking, in particular the closing words, spoken by the man we have just watched commit suicide in a deep-sea diving suit: Unfortunately, I cannot in this post effectively illustrate the creative variety of the film's soundtrack. The maps I have already sampled here. The film itself, in the credits, foregrounds the innovative underwater camera work, using the Eclair Aquaflex, a newly patented camera by Coutant: Just as remarkable, however, is the nudity in the film, made into a reflexive device when Perrucha (Françoise Arnoul) is told to undress for an audition: This sequence is characterised by varieties of gaze: the relative indifference of the man auditioning Perrucha ('I don't give a toss about your arse, I've seen fifty today'); the furtive scrutiny of the secretary; Perrucha's looking away from then directly at the man, and, self-reflexively, the camera's own tilting gaze, from her feet to her upper body: Her physique gets her hired but she refuses the job, saying that she doesn't want to display herself to people, she wants to sing and dance. The film will allow her to sing and dance, but it will also display her, naked, to its audience: The same irony is at work later when, in the cabaret where she is working, one of the acts sings, dances and performs a strip: This striptease ends before the performer is completely naked, as if the film were sharing her coyness before the public, while it is otherwise, in private, happy to undress its leading lady. More interesting, though, than maps, underwater cinematography or nudity, I would say, is the film's fixation on the look to camera, in particular on the gaze of Françoise Arnoul: Four of these looks to camera signify in conjunction with the soundtrack: the first is accompanied by applause as she imagines her success as a performer; the second is accompanied by silence as her lover, Mario, suggests they marry (she then closes her eyes, and we hear the whistle and engine of a locomotive); the third and fourth add expression to the song she sings (in a radio studio, then on stage). The last is more straightforward - she is hysterical because her lover is going to kill himself, thinking he has killed her. The fifth of these fourth looks is from the climax of the film, when Perrucha's lover strangles her. This sequence thematises the look to camera, firstly in that she doesn't recognise him. He approaches the camera, an extreme close-up that the next shot allows us to read as her point of view: Mario takes her in his arms and says 'Regarde moi bien', 'Look at me': A suggestion of reconciliation accompanies a look to camera in extreme close-up: His gaze falls on her open nightgown, returning us to the film's fixation on Arnoul's nudity, here thematised in conjunction with the intensity of the fourth look: This moment was isolated for a promotional film still, the one that provokes a reaction from Janine in La Petite Voleuse: Perrucha's reaction is to cover her breasts: Mario's anger returns when she refuses to have sex with him one more time (before he kills himself), and he strangles her. As he leans over her seemingly lifeless body the soundtrack echoes the locomotive sounds heard forty minutes earlier, and the intensity of her gaze is transferred to him: I know of no film of this type or period so intensely centred on the look to camera, nor any so 'daring', as the publicity puts it, in its display of nudity. Three years later, Rozier directs Brigitte Bardot in a film that promises nudity in its title, Manina ou la fille sans voile, but which delivers only a succession of louche men ogling Bardot in her bikini: The look to camera is reserved, in 1950s French cinema, for comic asides, most often as the film closes, for example in Bernard Borderie's Lemmy Caution films: Or in Michel Boisrond's Une Parisienne: Aside from this glimpse of Janine in a mirror, looks to camera in La Petite Voleuse occur only in the authentic newsreel footage shown near the beginning of the film: And in the fake newsreel watched by Janine towards the end of the film: Despite being made almost forty years after L'Epave, La Petite Voleuse is much more reluctant to show its female star naked: In searching for postcards of villas or châteaux that match some buildings seen in early French cinema (see e.g. here), I have come across a number of strikingly quirky examples, of which here is a selection: Some edifices of this type have survived. Here are some of my favourite xamples from the Topic-Topos site, a catalogue of France's architectural patrimoine:

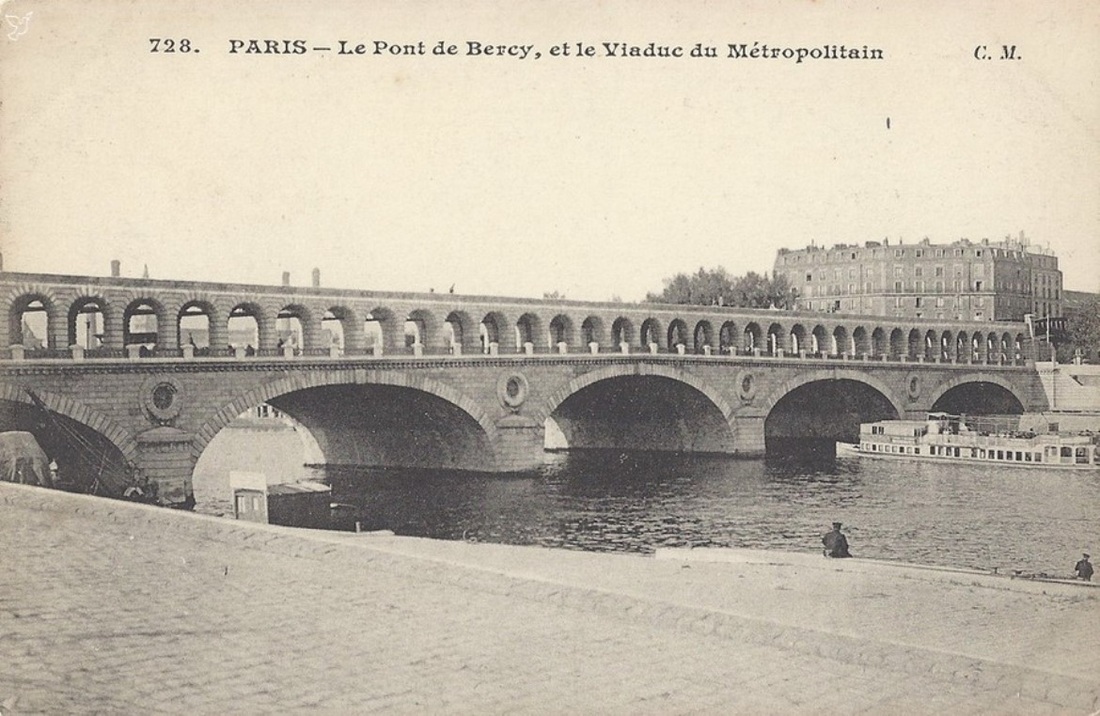

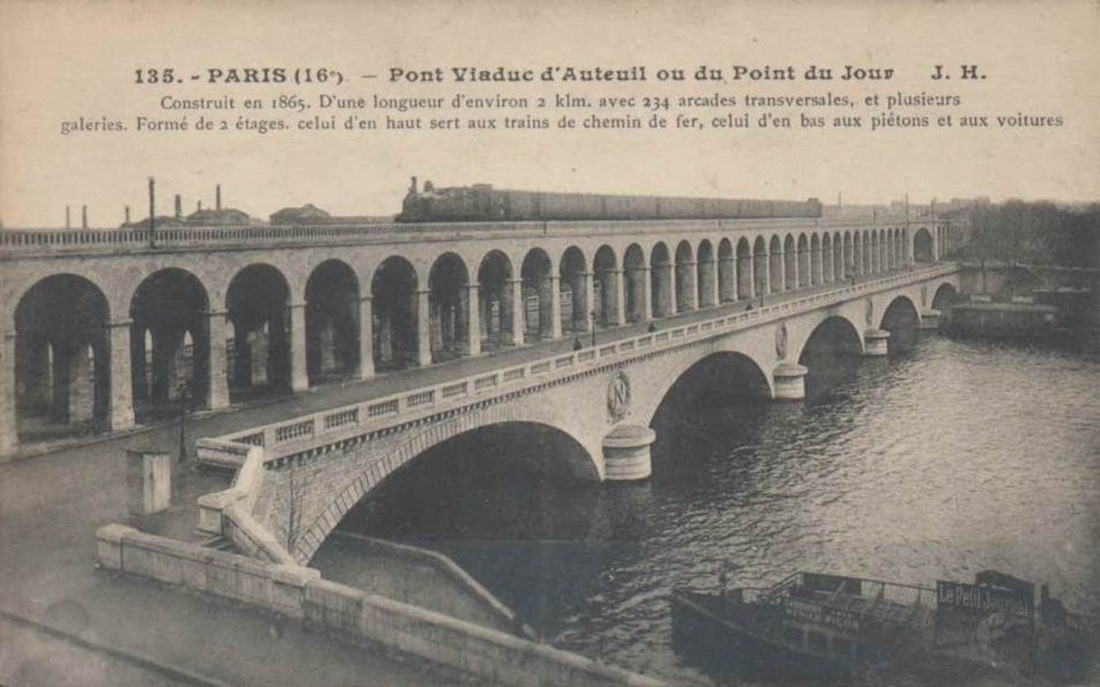

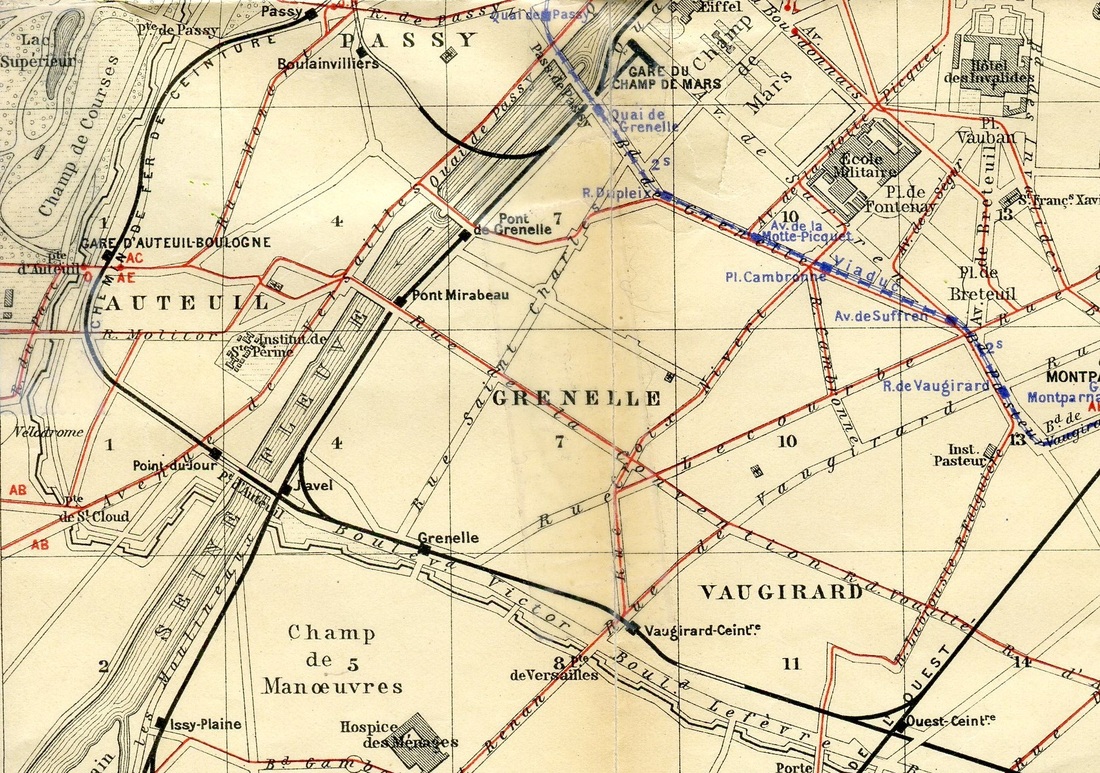

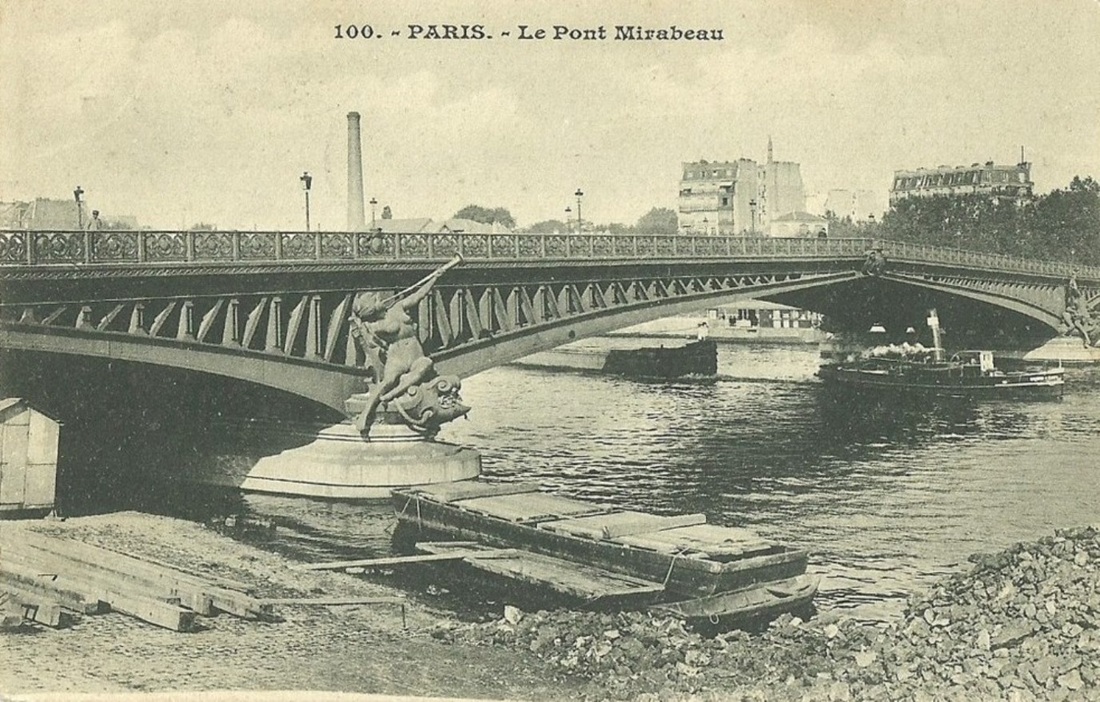

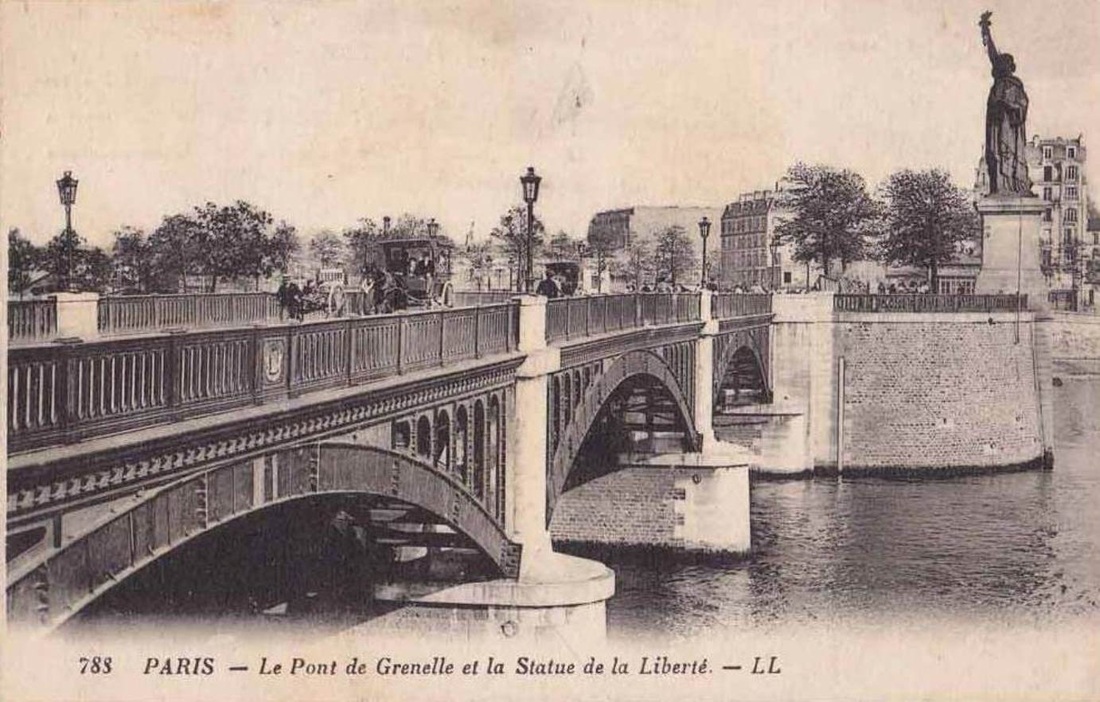

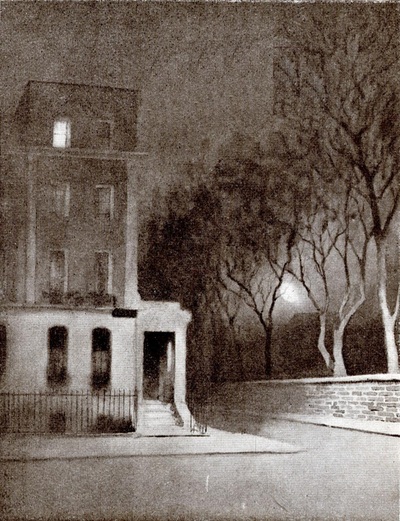

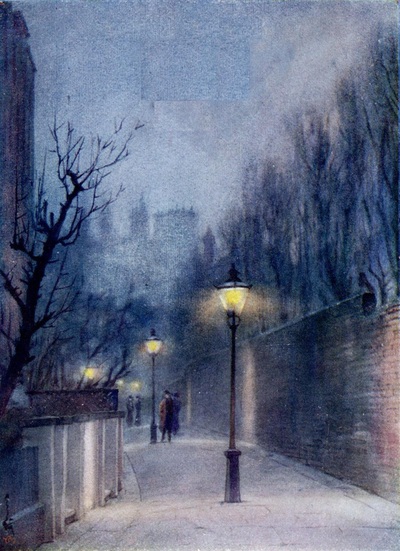

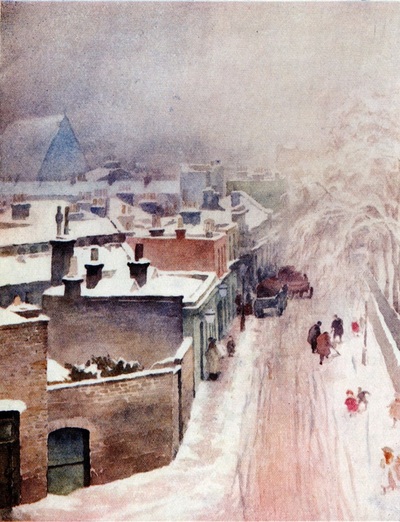

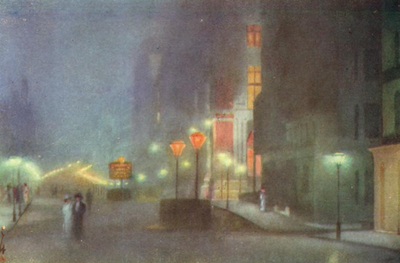

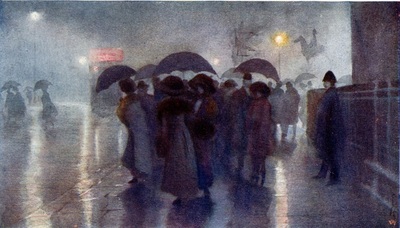

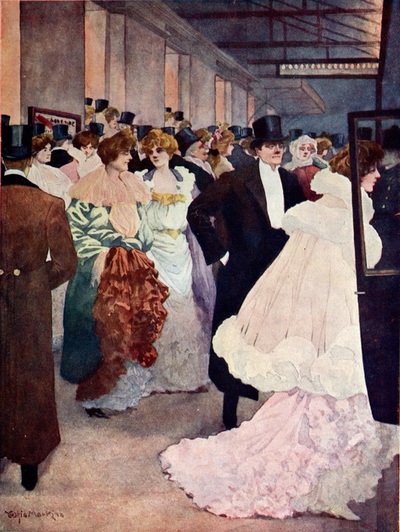

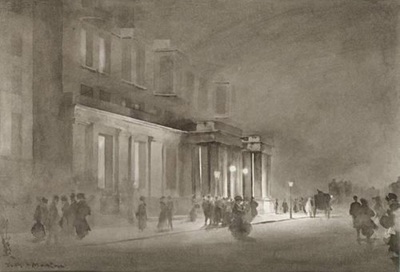

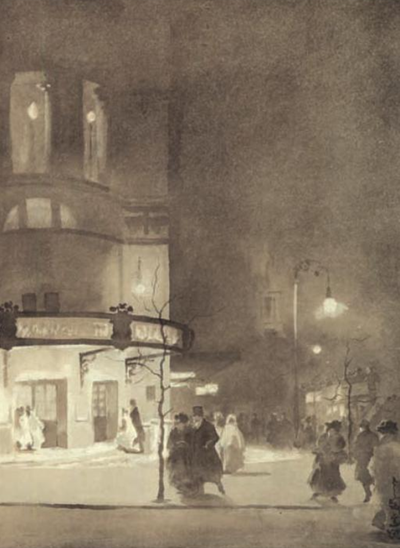

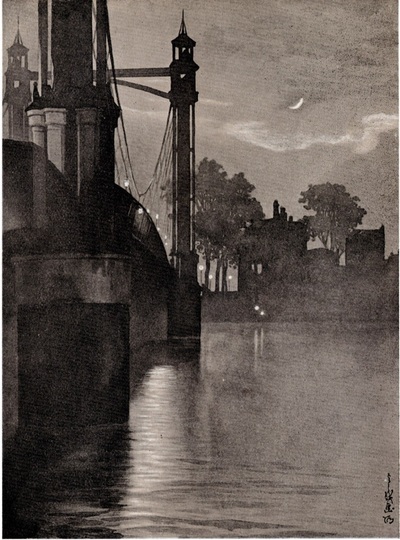

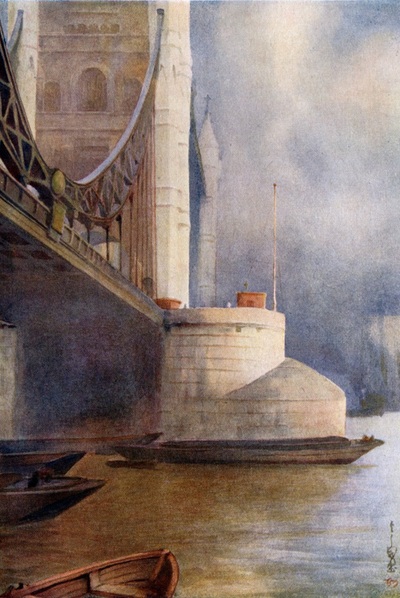

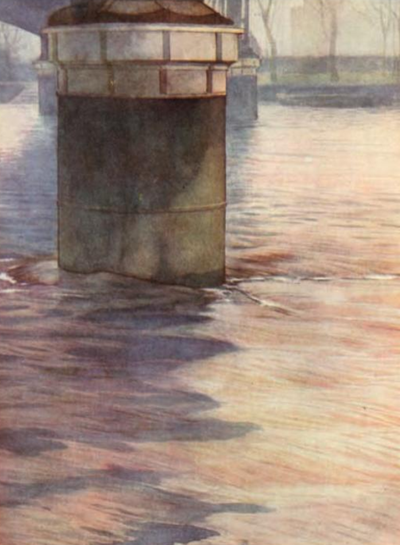

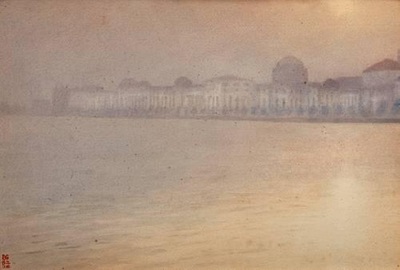

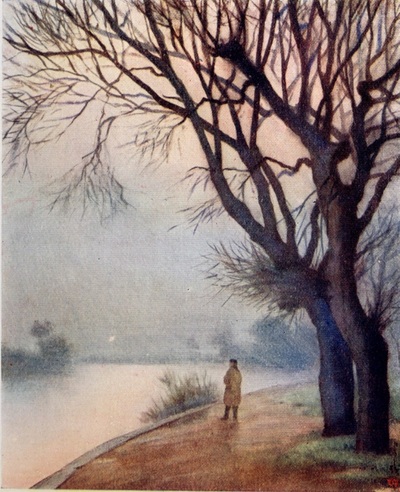

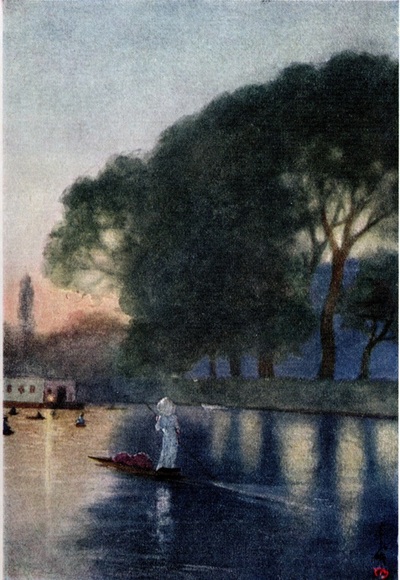

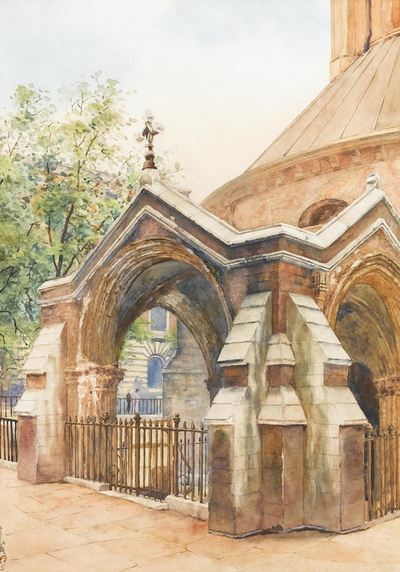

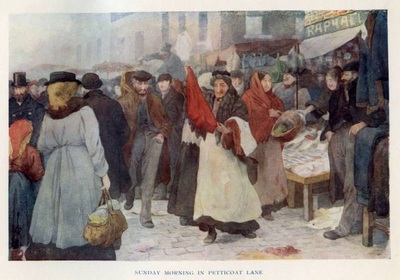

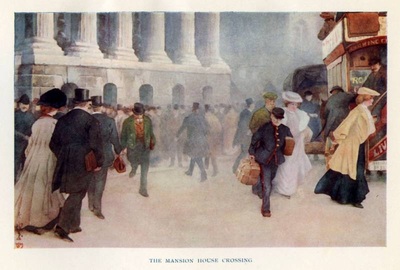

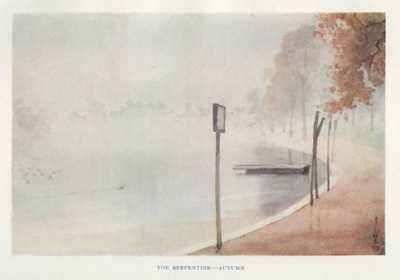

Coming across this print by Mary Cassatt in the January 1959 issue of the art journal L'Oeil, my first thought was to ask what bridge is that in the background. There are two possibilities, the pont de Bercy: And the pont du Point du Jour, or pont d'Auteuil: Cassatt's print is dated 1891, and the pont de Bercy didn't acquire its métro-bearing viaduct until 1909, so it must be the pont du Point du Jour, built 1865. The other place to be identified is the viewpoint. Is Cassatt looking upstream towards Paris or downstream out of the city? The print's title is 'En Tramway', and seems to represent a view from a tram on a bridge. This 1904 map shows that there is no bridge downstream, so it has to be a bridge north of the pont du Point du Jour: In the accompanying essay Adelyn Breeskin tells us that Cassatt had called the print 'Dans le bateau mouche', and if the viewpoint is in fact from a boat on the river we could be looking in either direction, but Breeskin argues that the viewpoint is clearly from an elevated position, such as a bridge, rather than closer to river level. From the map above that bridge would appear to be the pont Mirabeau: But the pont Mirabeau dates from 1893-96, so couldn't have supplied Cassatt with a viewpoint in 1891. She must be on the next bridge up, the pont de Grenelle, built 1874: We can see from this postcard that the bridge was used by trams: The viewpoint is not quite central - if it were the Statue of Liberty would be in frame. The scale model of Bertholdi's 'La Liberté éclarant le monde' was put in place in 1885. We can suppose that the tram has just passed the statue, and speculate that the woman is gazing upon it: Or she may be thinking of something else entirely. Something that troubles my thoughts is the position of Bertholdi's statue in the two postcards above. The first is a view north to south and the second is south to north. In both the statue looks east, towards Paris. That is not the statue's current position: Things have changed since Mary Cassatt's passengers crossed the pont de Grenelle in 1891. There aren't any trams; the bridge itself has been replaced with a new one (built 1968); there is no longer a view of the pont du Point du Jour - it was demolished in 1962; and the Statue of Liberty now faces west, turning her back on Paris: She is looking towards the pont Mirabeau. Perhaps she is wondering where the pont du Point du Jour has gone. Or she may be thinking of something else entirely. The INHA site has two versions of Cassatt's image, titled 'Dans l'omnibus', an outline and a finished version less darkly coloured than the reproduction in L'Oeil: Source: Adelyn D. Breeskin, 'Mary Cassatt graveur', L'Oeil, 49 (January 1959), pp. 40-45, 70. This is a sample of the London images by Yoshio Markino (1869-1956) that can be found on the Net.

Sources include the following:

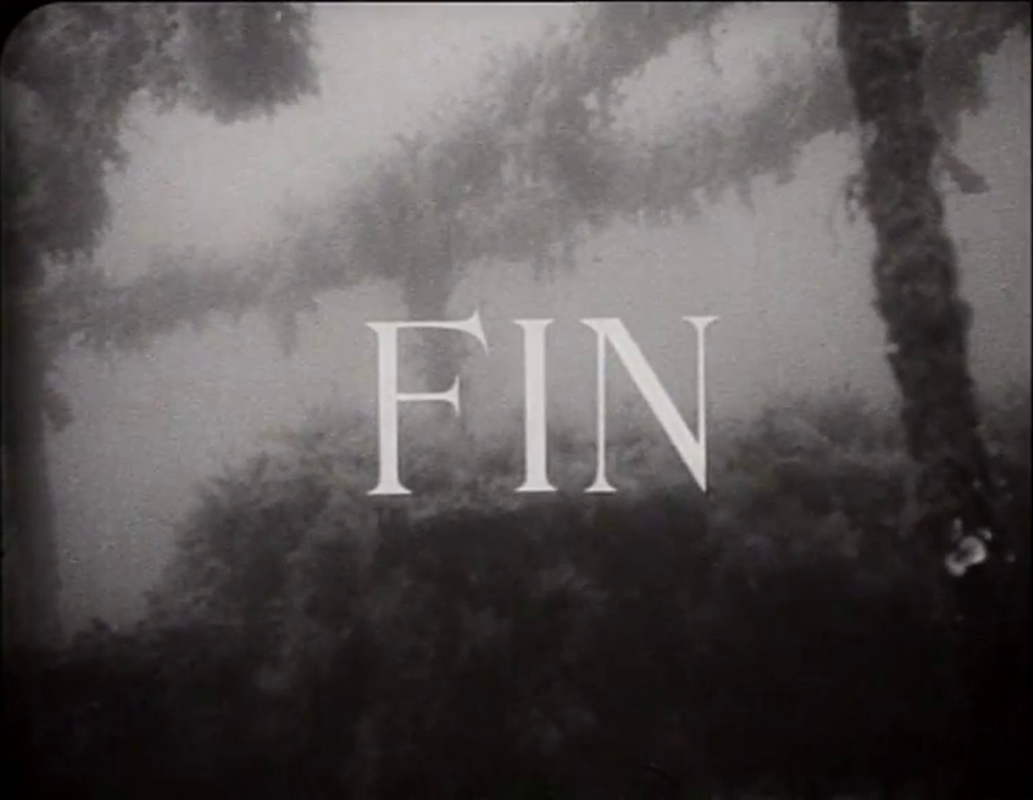

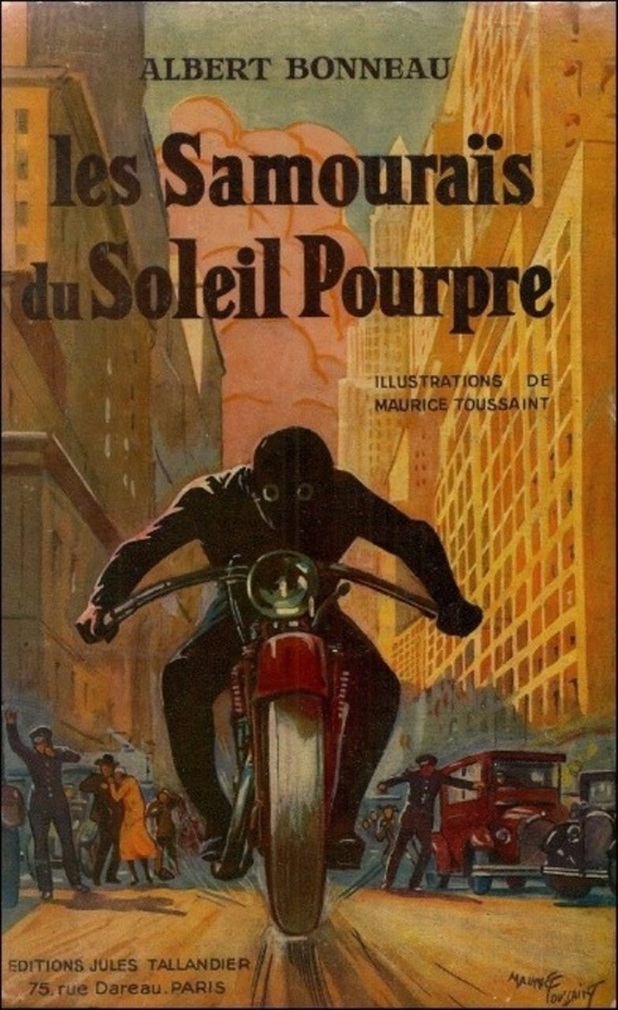

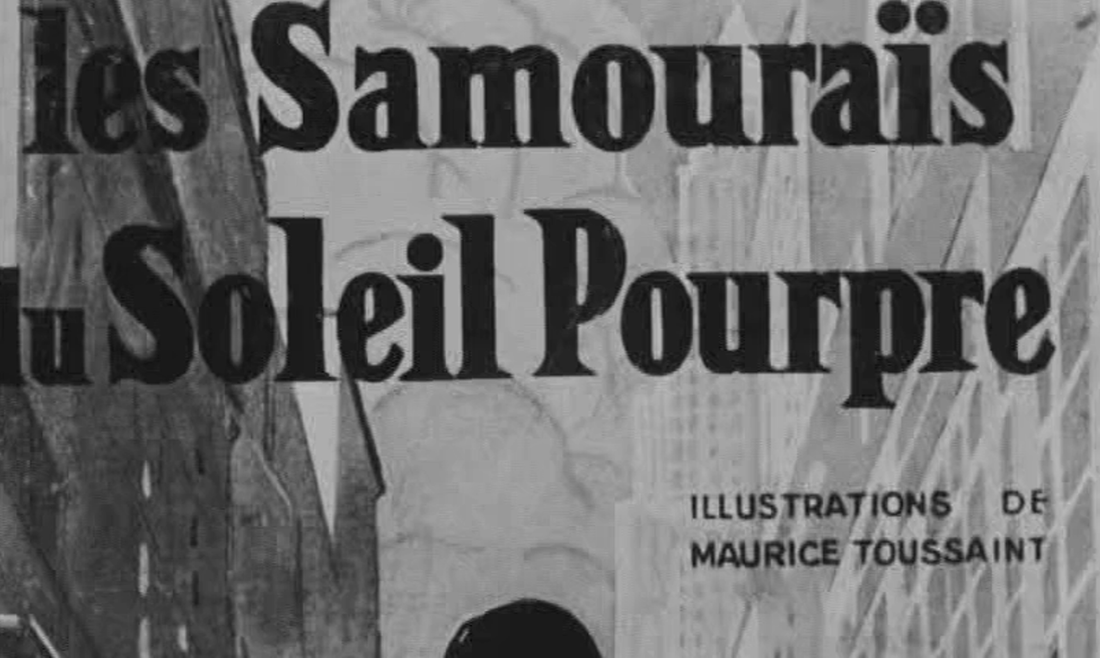

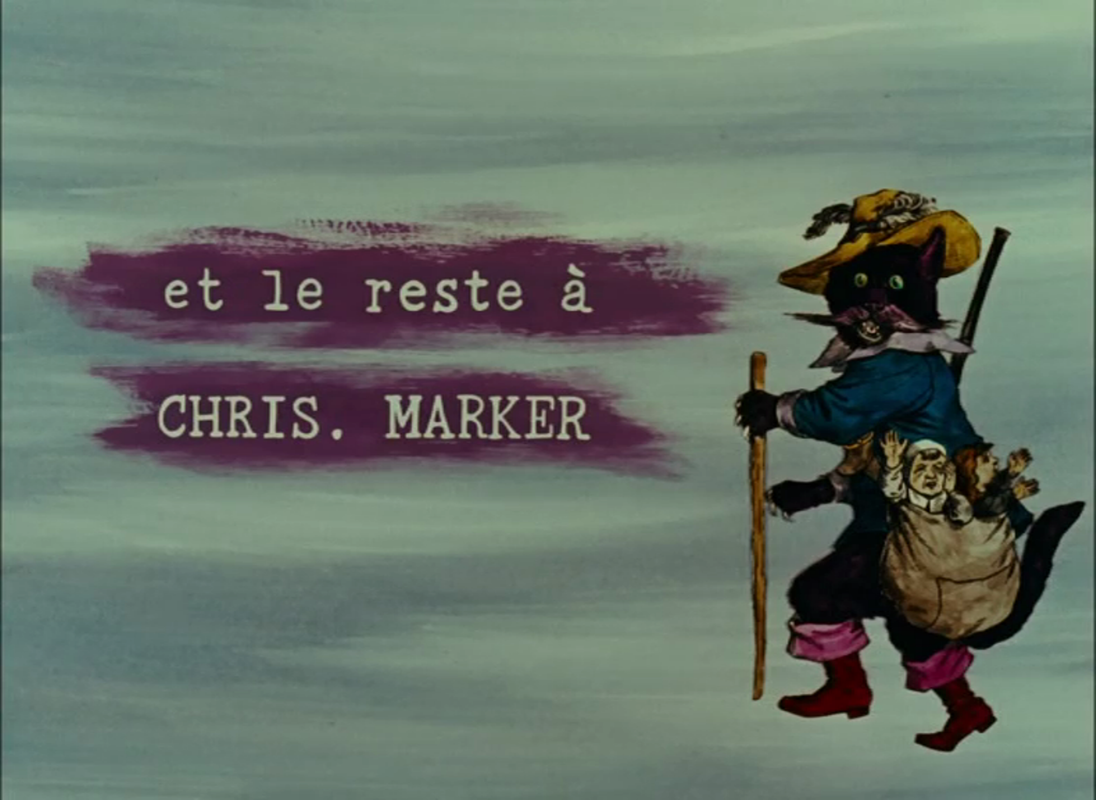

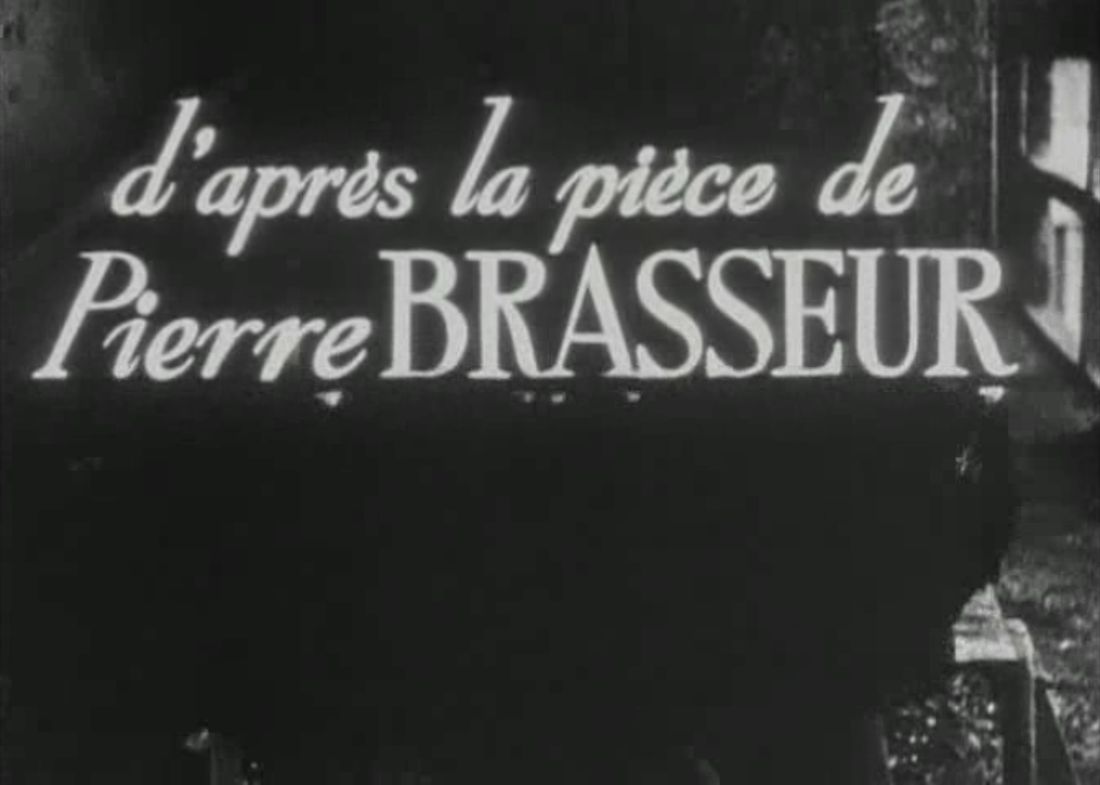

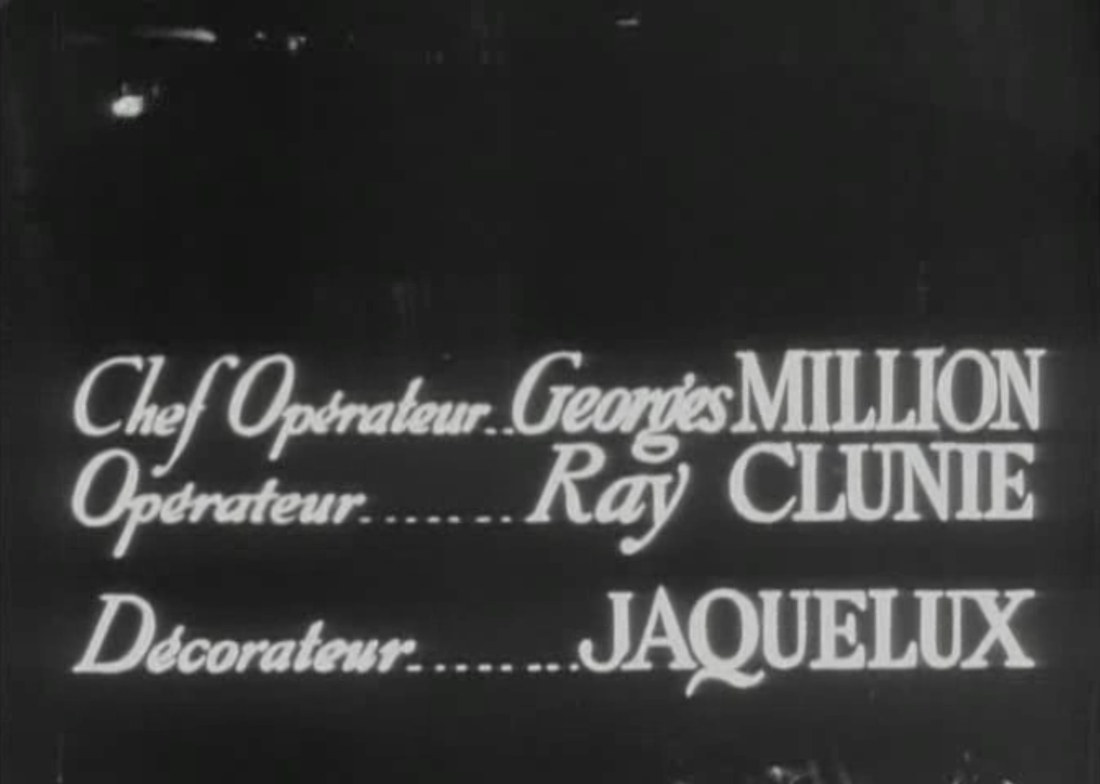

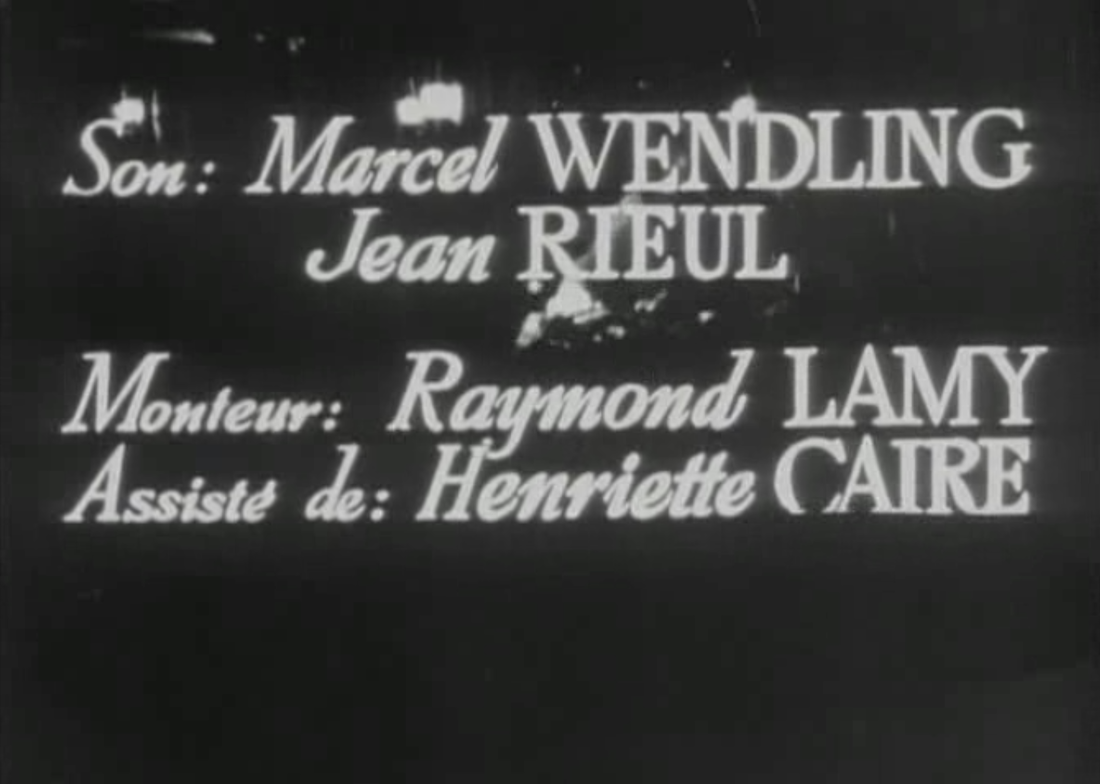

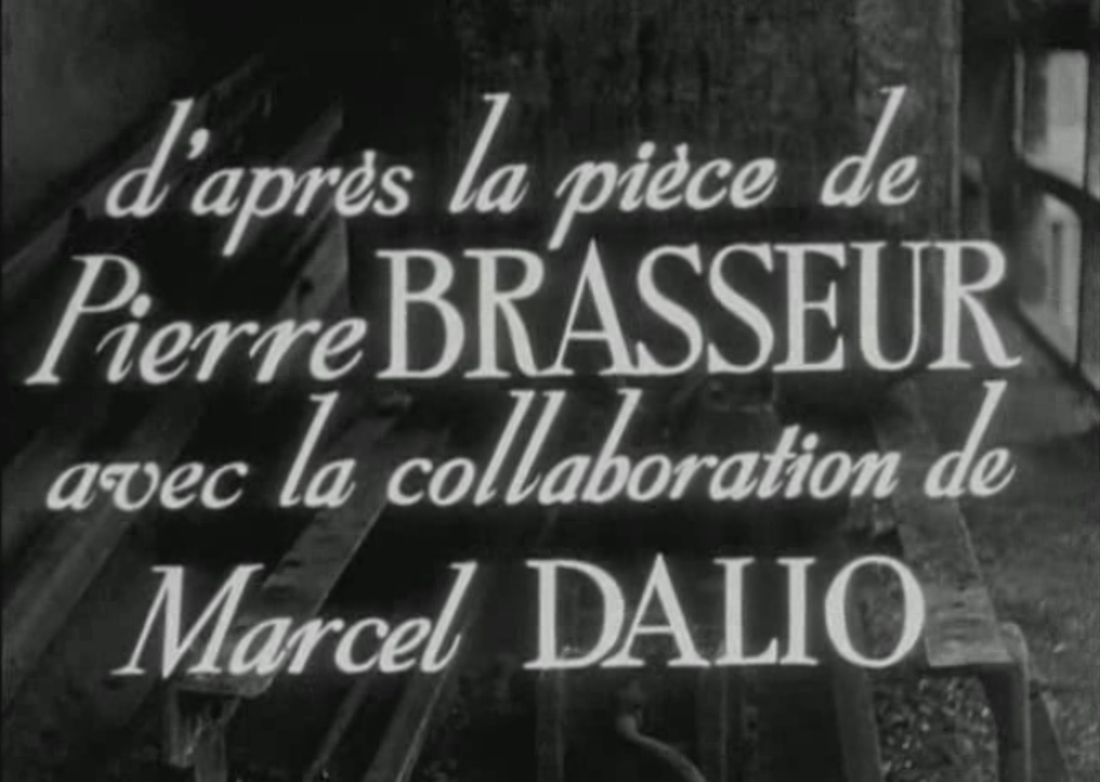

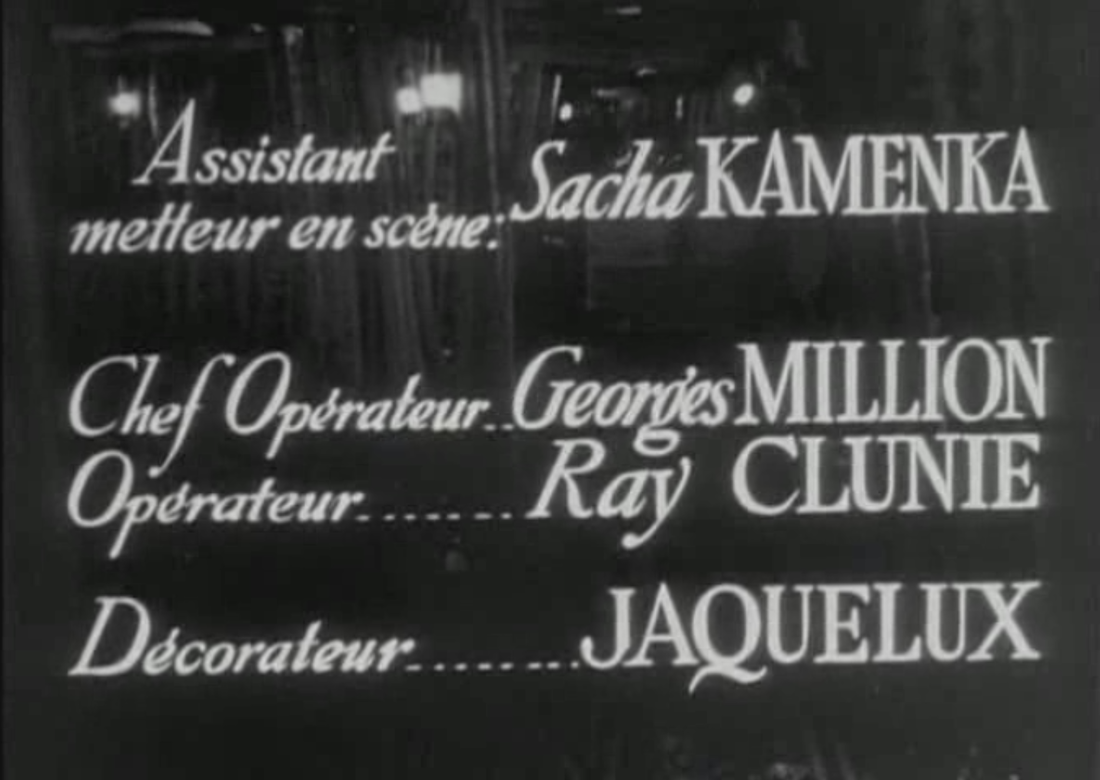

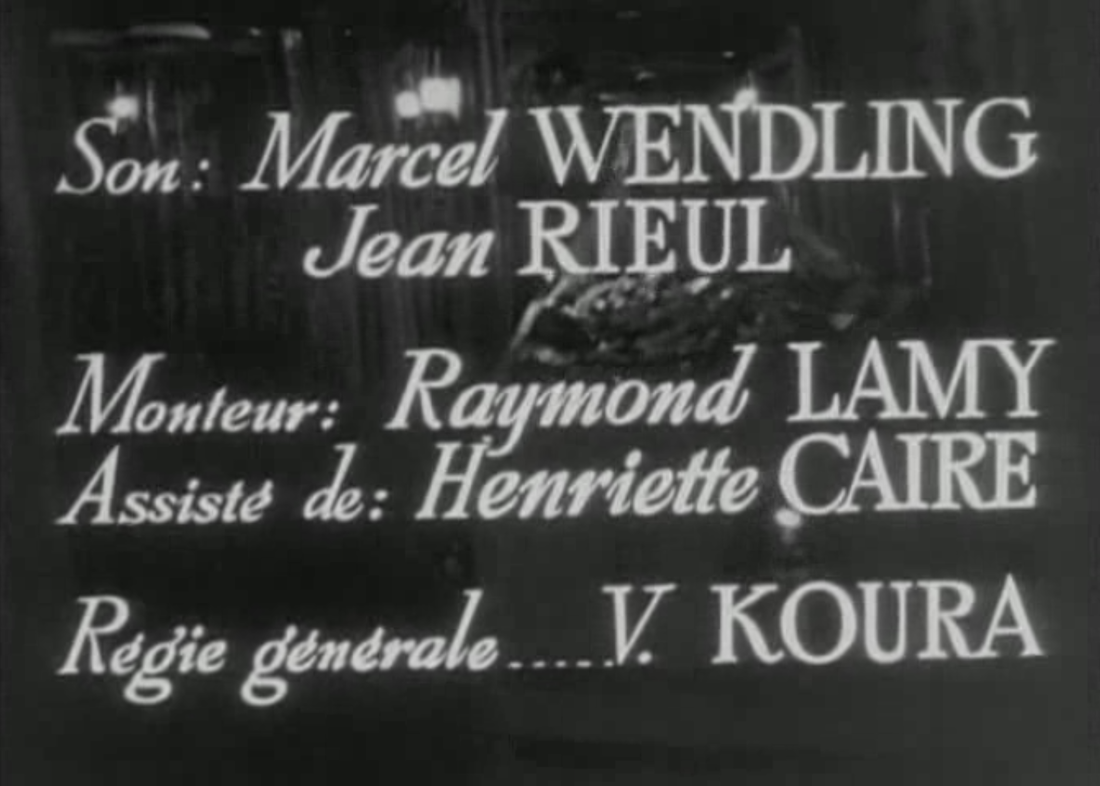

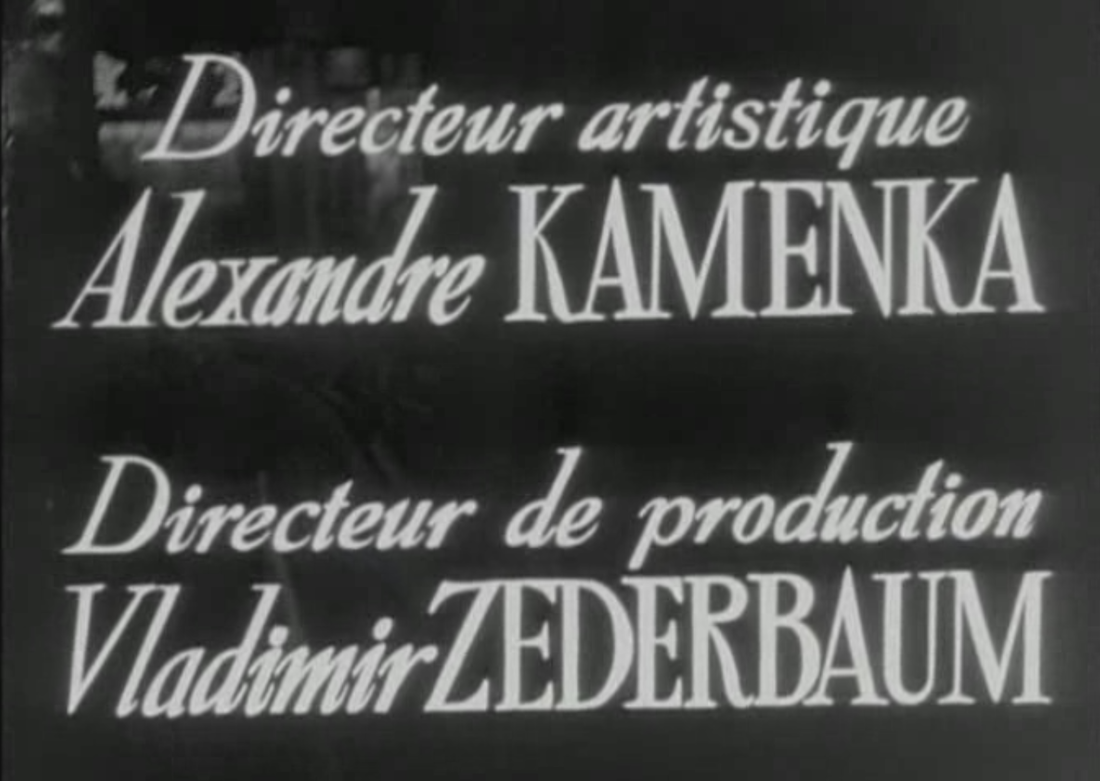

There are, if I have counted correctly, ten cats in Chris Marker and Pierre Lhomme's Le Joli Mai, including the graffiti cat above, the first to appear. The last is the cat belonging to the theatre seamstress, who has made a complete outfit for her cat: She also has two drawings of cats in costume: (That makes a total of twelve, actually - I miscounted.) The other eight appear as inserts or interludes, mostly in close-up: The last of these gets special treatment, its gaze matched to that of the hooded motorcyclist on the cover of a book that was a favourite for Marker in his childhood: However, we barely get the chance to appreciate the match between cat and man because the camera whip-pans upwards so quickly that all we see is the top of the book cover: The vis-à-vis is a joke for the benefit of those who can slow down or freeze the image: Here are some cats in some other films by Marker: And here are some other cats in some other films: The 1942 re-release of Grisou, a 1938 Albatros production shot in the mines of Lens, northern France, was given an alternative title, 'The Men Without Sunlight'. 'Grisou' mean firedamp, the gas in coalmines that leads to explosions. I'm not sure why the new title was given, unless it was to fool cinema-goers into believing this was a different film from the one they might have seen four years earlier. Easier to explain are the other changes to the credits. Four pages appear in 1942 with curious black smudges over some of the wording, as if someone has tried to efface some of what was written: That is, more or less, what has happened. A notice at the beginning of the René Chateau dvd explains that the German authorities during the Occupation had permitted the distribution of the film on condition that the names of anyone Jewish be removed from the credits. Here are those pages from the 1938 version of the film (the René Chateau dvd includes both sets of credits, as historical testimony): The first name suppressed is that of Marcel Dalio, the great actor, though his involvement in this film was only as assistant to Pierre Brasseur in the adaptation of his play for the screen. Next is the assistant director, Russian-born Sacha Kamenka (later to be production manager on Hiroshima mon amour). Then it is the assistant V. Koura, who had earlier worked alongside several other names from these credits on Jean Renoir's Les Bas-fonds (1936), another Albatros production. I haven't found anything else about Koura (not even what the 'V' stands for). The fourth name to be suppressed is that of the band leader and composer Ray Ventura, later to become a familiar figure in French film musicals. (And he was Sacha Distel's uncle). As well as blacking out these names the 1942 credits cut a fifth page entirely, suppressing two further names: Alexandre Kamenka, father of Sacha, was born in Odessa in 1888, and was one of the founders of the Albatros production company. Zederbaum was a close associate in the running of the company. I haven't before seen so crude a mode of censorship as the scrubbing out of names in the credits, and would be interested to hear (here) of other examples. Of a different order of interest are the film's closing credits, or more exactly the novel device used to signal that the film has finished. Down in the mine, we see someone pushing a truck full of coal, moving from back to front of the space. On the truck is written the word 'FIN', which grows larger until it dissolves into the production company logo: |

choses vues ...

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed