Place de la Concorde c.1900: Nadar, Lumière, Edison...

Among the many rarities made available to watch by the Cinémathèque this summer (see Henri, here) is a collection of films made by the photographer Paul Nadar, son of Félix. Of particular topographical interest are the last two films of the ten, both views taken at the Place de la Concorde:

The Place de la Concorde was a favoured location for cinematographic views. As well as Marey with his chronophotographic camera c.1897, there was De Bedts in 1896, Méliès in 1896 and 1897, Normandin in 1897, Gaumont in 1897 and Pathé in 1897 and 1900; there are three views in the Lumière catalogue, all currently dated to 1896-98. W.K.L. Dickson filmed there in 1897 for the British Mutoscope and Biograph Company, as did James H. White for the Edison company in 1900.

The location was popular not only because of its fame and visual distinction, and not only because it was always busy with traffic, both vehicular and pedestrian, but also because in this vast square there were numerous islands on which an operator could safely position the camera, and indeed move it - the Pathé and Edison films from 1900 are 'circular panoramic views'.

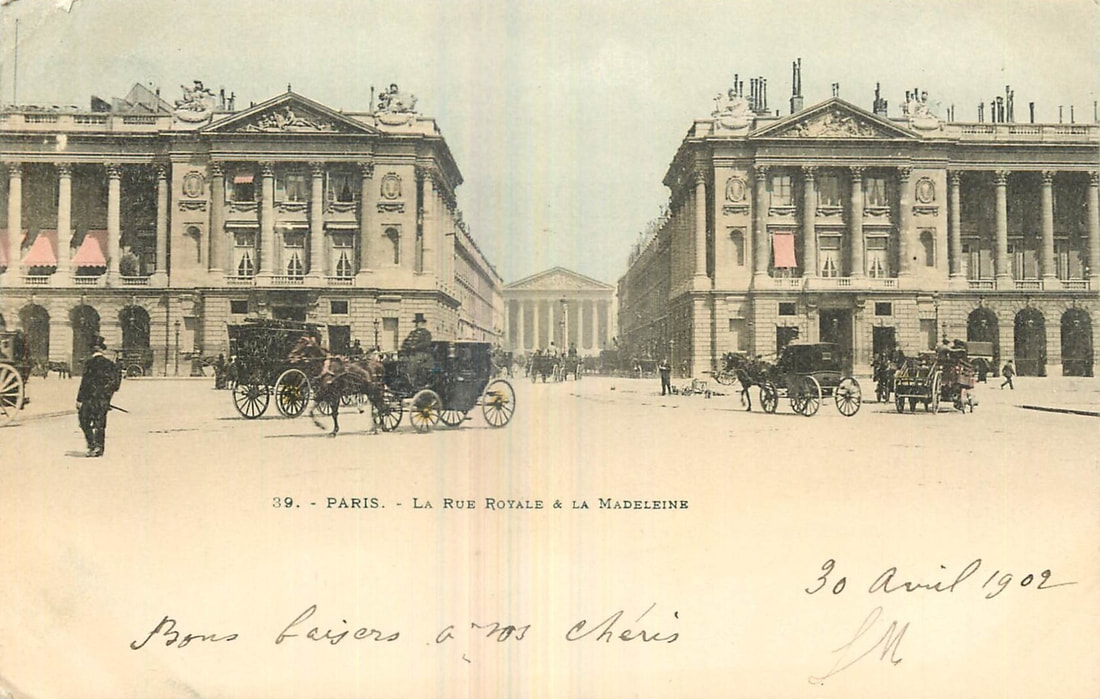

The view that chiefly interests me in this post is the one by Paul Nadar looking down the Rue Royale from the Place de la Concorde towards the church of La Madeleine. At first sight it is a conventional street view, registering architecture, street furniture, vehicles and pedestrians, some of whom look curiously at the camera and operator as they pass through the field of vision. In this respect it closely resembles the Lumière view entitled Place de la Concorde et entrée de la Rue Royale:

I think that in each case the camera was on the central island, just to the left of the more distant fountain in the image below:

The Lumière and Nadar views showing the Rue Royale and La Madeleine are similar but they differ in one significant respect. In Nadar's film, among the twenty or so unsuspecting pedestrians who pass through the fore- or mid-ground in front of the camera there are two men who are there to act out a scene. We see them first crossing right to left:

The further of the two is bearded, wearing a top hat, a long dark coat and lighter trousers; the nearer man is less distinctively bearded, wears a slightly longer and lighter-coloured coat, and a hat something like a derby or bowler. He has a large paper document in his hand which he is trying to show to the other man. That document is, I am almost certain, a map.

They exit frame left, and a few seconds later the man with the map crosses left to right, alone:

He exits right but seems to stop for a while just outside of the frame - we can see the edge of his map at the edge of the screen as he continues to consult it. A few more seconds elapse and then the man with the top hat crosses in front of the camera, right to left:

When we last saw him he was exiting left with the map man, so he must have come round to the right by passing behind the camera.

There is a jump in the film when this man almost reaches the left edge, so we don't see him exit, but we do very soon see him enter again, from the left. He is met in front of the camera by the other man, who once again attempts to get him interested in the map. The man in the top hat first looks at it, then walks away, then is persuaded by the other to look again at the map, but he walks away again, exiting right, leaving the map man's problem unsolved, it seems:

There is a jump in the film when this man almost reaches the left edge, so we don't see him exit, but we do very soon see him enter again, from the left. He is met in front of the camera by the other man, who once again attempts to get him interested in the map. The man in the top hat first looks at it, then walks away, then is persuaded by the other to look again at the map, but he walks away again, exiting right, leaving the map man's problem unsolved, it seems:

If this staged scene has passed unnoticed it is probably because we do not expect documentary views to be complicated by the fictional. I can think of views where some of the people we see have clearly been positioned there to be filmed, but I can't think of many where those people are then supposed to act out some kind of business. Mme Lumière, who awaits the arriving train at La Ciotat, isn't on that platform by chance, but she cannot be said to be playing a prepared rôle. On the other hand, the 1898 Pathé film of a train arriving at Auteuil-Boulogne station, supposedly a documentary view of the same type, shows a distracted man on the platform knocked over by a passing cyclist in what is clearly a staged scene:

The scene in Nadar's Rue Royale film may have passed unnoticed because it was ineptly staged. Be that as it may, I cannot help but be excited at this early instance of a map being consulted in a film. It adds a contemporary, real-world instance to these other maps from the period, in the 1897 historical Lumière production La Mort de Marat and in Méliès's 1898 fantasy La Lune à un mètre:

Depending on its date, Nadar's film could be the first ever to show a map. Herein lies a difficulty. Some of the Nadar films, those found in the Auboin-Vermorel collection, can safely be dated to 1896-97; the others, including the topographical films, were acquired by Langlois from Nadar's widow, and the dating is less precise. (I am grateful to Laurent Mannoni for this clarification.)

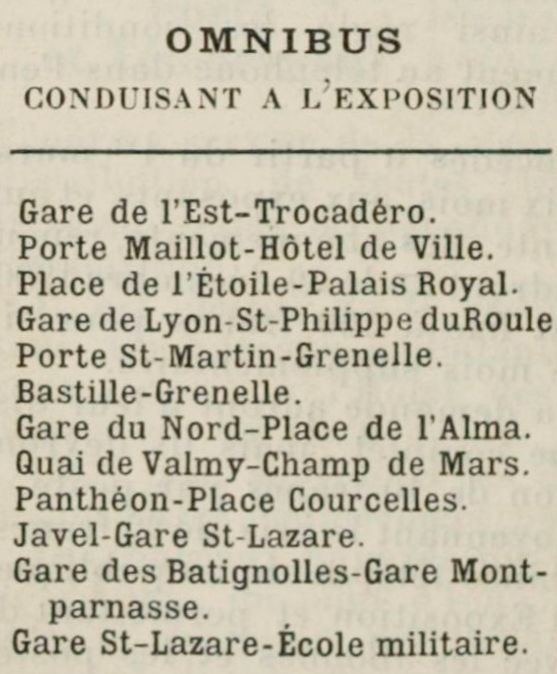

Evidence internal to the Concorde/Royale film does suggest a specific date. As well as pedestrians there are carts, carriages, cabs and omnibuses in the film. Of these last there are seven in total, and on four of them it is possible to read signage indicating their routes. The first, a 'C', is on its way from the Porte Maillot to the Hôtel de Ville. It is also indicated that it serves the Jardin d'Acclimatation and the Louvre:

This omnibus is also a 'C', heading for the Porte Maillot:

|

The omnibus below left is a 'C bis', which ran between the Place de l'Etoile and the Palais Royal. Those place names are hard to make out, but what is clearly legible is the panel indicating that this omnibus serves the 'Exposition'. The 'bus below right, with a different livery and on a different route (heading up towards La Madeleine rather than along the Rue de Rivoli), also carries a panel with the word Exposition: |

|

The clear implication is that Nadar's 'Rue Royale' film was not made in the time period hitherto given, between 1896 and 1898, but at some time between April and November 1900, during the run of the Exposition Universelle.

This photograph, taken at the time of the Exposition, shows a 'C bis' omnibus passing the Avenue Alexandre III (now Avenue Winston Churchill): |

|

There are omnibuses in the other topographical film from the Nadar collection, 'Place de la Concorde', but they don't come close enough to the camera to allow their signage to be read. I would tentatively conjecture that the panel on the 'bus here is of the same size and in the same position as the 'Exposition' signs in the Rue Royale film: |

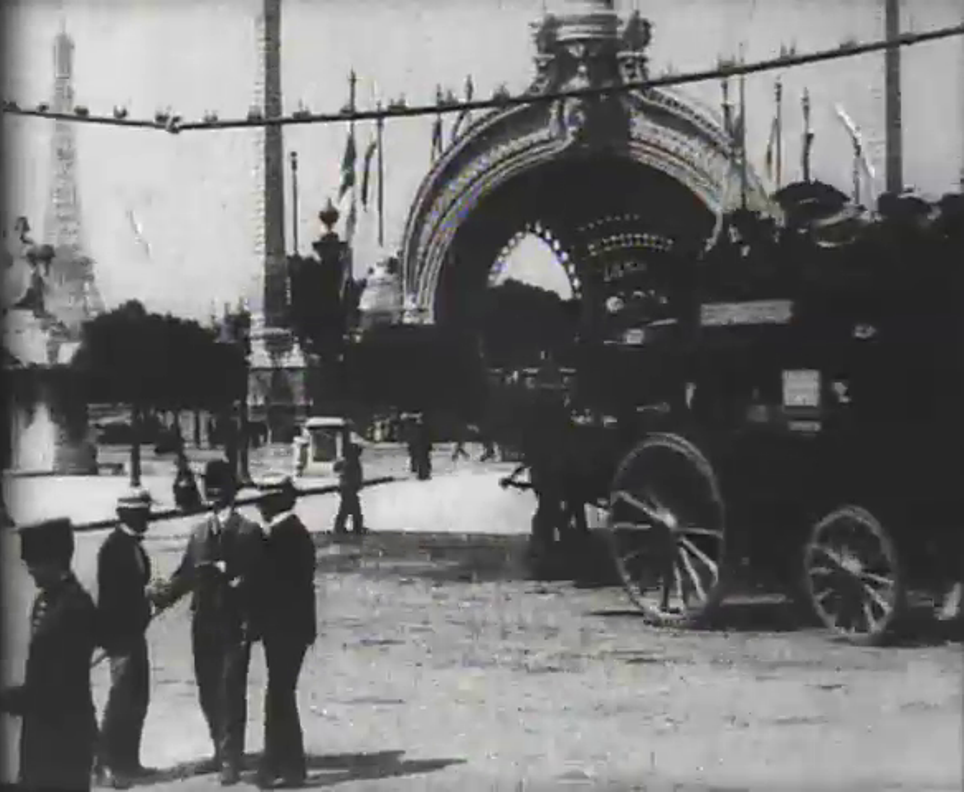

James H. White's panoramic view of the Place de la Concorde shows an 'Exposition'-panel-bearing omnibus in front of the exhibition entrance:

Exposition-related signage allows us to suggest a corrective to the attributed date of another film from this period. The three 'Place de la Concorde' films made by the Lumière company are all dated 1896-97 on the online catalogue, which is based on Michelle Aubert and Jean-Claude Seguin's 1996 publication La Production cinématographique des frères Lumière:

This dating is based on newspaper reports of screenings in April and November 1897, but those reports just give the title 'Place de la Concorde', so it is not possible to tell which of the three films was screened when, or indeed whether it wasn't the same one each time. Catalogue entries from 1897 give more specific titles: 'Place de la Concorde (vue prise du côté ouest)', cat no. 153; 'Place de la Concorde et entrée de la Rue Royale', cat. no. 692; 'Place de la Concorde (obélisque et fontaines)', descriptions that match the films we have.

There is a problem, however, concerning film 692, in that we can clearly see passing infront of the camera

an omnibus bearing the sign 'EXPOSITION', exactly as in the Nadar film taken from the same place:

There is a problem, however, concerning film 692, in that we can clearly see passing infront of the camera

an omnibus bearing the sign 'EXPOSITION', exactly as in the Nadar film taken from the same place:

If that is an omnibus taking passengers to the 1900 Exposition Universelle, then this cannot be the film catalogued in 1897 under that title.

There are two possible explanations for this anomaly. One was suggested by Clive Lamming, author of Les Omnibus 1829-1913: 'The organiser of an exhibition could request a special service and one or several omnibuses, which would be parked at a railway station, for example, and be identifiable by the "Exposition" sign' (private correspondence).

Without going so far as to say that by his clothing he is coded as such, I would conjecture that the man with the map is supposed to be a stranger to the city, and that he is seeking directions