|

neon Paris c. 1913

Following on from the electric nights in Paris post two weeks ago, this is an attempt to elucidate a few details concerning the first appearance of neon signage in Paris c. 1913. All accounts seem to agree that the first public manifestation of neon's distinctive reddish glow was at the 1910 Salon de l'Automobile, where Georges Claude decorated the façade of the Grand Palais with four neon tubes thirty-six metres long (La Machine moderne, janvier 1911). Le Figaro of December 12 1910 reported: 'Immense success for Georges Claude's red light. The "neon" tubes triumphed yesterday.' |

We can appreciate for ourselves the effect of Claude's installation thanks to the early enthusiasm for neon of photographer Léon Gimpel. He photographed the Grand Palais at night and in colour:

Here a first confusion about dates arises. The first of these photographs is dated 1919 in Ulmer and Plaichinger's generally reliable Les Ecritures de la nuit, but that is clearly a typographical error. In other sources it is dated sometimes 1910 and sometimes 1912. The second photograph is usually dated 1912. Georges Claude decorated the Grand Palais in both years (though not in 1911, it seems). In December 1912 L'Aéro reported that 'the fiery red incandescence of the exterior columns is due to Georges Claude's Neon tubes', adding in conclusion that 'like every year, light is the great success of the Salon de l'Automobile'. Whether from 1910 or 1912, these two photographs show well how impressive was this novel form of illumination.

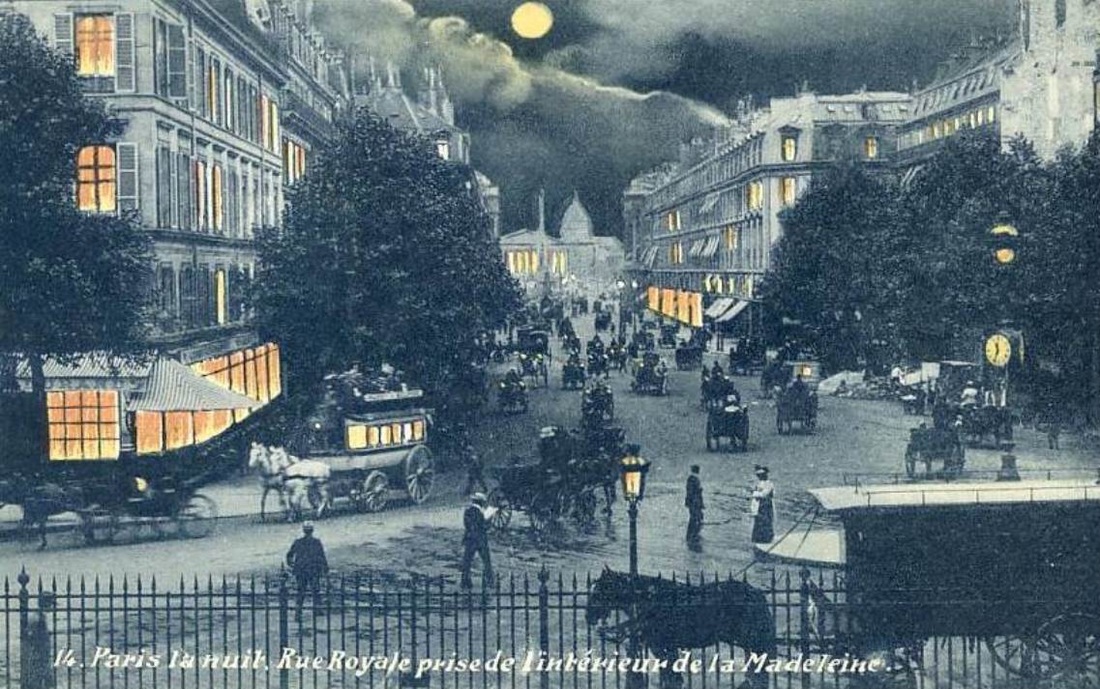

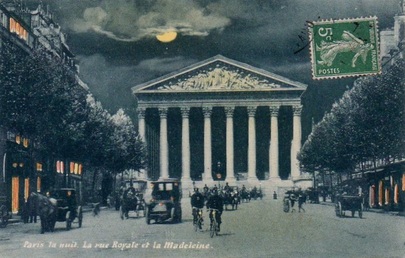

The first use of neon for advertisement rather than decoration may be a tube used 'to underline the inscription "Porto Sandeman" on a shop at 5 rue Royale' - in 1910, apparently, though I have found no corroboration of this date outside of John Compton's 1980 essay. I have found no image of the Sandeman shopfront on the rue Royale (next door to Maxim's), but here are two views of this street at night, both with added tints of a neon-like orange:

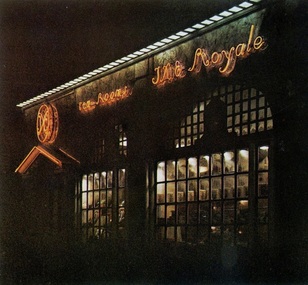

And here are two views of neon signage from the 1920s, at the Ixe Tea Rooms, 24 rue Royale:

The big leap forward in the use of neon came when the tubes were made thinner and more malleable, meaning that they could be shaped into letters and used as signage. The first neon sign of this type is always dated to 1912. The origin of this claim seems to be Jacques Fonsèque, of the Paz et Silva lighting company with which Georges Claude was associated. Fonsèque's unpublished memoirs were used by Ulmer and Plaichinger for their book Les Ecritures de la nuit:

'M. de Beaufort, from the Claude workshop, had the idea of reducing the diameter of the incandescent tubes and making the electrodes smaller so that the tubes could be shaped into a continuous line of letters. The tests were so quickly conclusive that a first neon sign appeared in 1912. "Palace Coiffeur" shone out from the façade of a hair salon frequented by directors of the Paz et Silva company, at 14 boulevard Montmartre. (Les Ecritures de la nuit, p.24)

'M. de Beaufort, from the Claude workshop, had the idea of reducing the diameter of the incandescent tubes and making the electrodes smaller so that the tubes could be shaped into a continuous line of letters. The tests were so quickly conclusive that a first neon sign appeared in 1912. "Palace Coiffeur" shone out from the façade of a hair salon frequented by directors of the Paz et Silva company, at 14 boulevard Montmartre. (Les Ecritures de la nuit, p.24)

An often quoted version of this story appears in Rudi Stern's 1988 book The New Let There Be Neon (p.8):

'In 1912 Fonsèque [Georges Claude's associate] sold the world’s first neon advertising sign to a small barber shop called Palais Coiffeur on the Boulevard Montmartre.'

There are three things wrong with the Stern version. Firstly, as we know from Ulmer and Plaichinger, the shop was called Palace-Coiffeur, not Palais Coiffeur. Secondly, this was not a 'small barber's shop' but a substantial emporium, staffed by twenty five of Paris's finest artistes. Contemporary newspaper reports relate that the salon offers 'the latest word in modern comfort and genuine luxury', that it is a 'temple of refinement' (Le Gil Blas 23.6.1913); it is 'the most luxurious, the most modern, and also the largest' establishment in Paris (Le Figaro 3.11.1913); to the Palace-Coiffeur 'the most prominent figures of Parisian high society' come to be coiffed (Le Journal 12.11.1913). The third thing wrong with the usual account is the date. The Palace-Coiffeur opened in June 1913. To signal the splendour of the establishment a neon sign was commissioned from the company of Paz et Silva. Neon advertising did not begin modestly or tentatively, and it did not begin in 1912.

'In 1912 Fonsèque [Georges Claude's associate] sold the world’s first neon advertising sign to a small barber shop called Palais Coiffeur on the Boulevard Montmartre.'

There are three things wrong with the Stern version. Firstly, as we know from Ulmer and Plaichinger, the shop was called Palace-Coiffeur, not Palais Coiffeur. Secondly, this was not a 'small barber's shop' but a substantial emporium, staffed by twenty five of Paris's finest artistes. Contemporary newspaper reports relate that the salon offers 'the latest word in modern comfort and genuine luxury', that it is a 'temple of refinement' (Le Gil Blas 23.6.1913); it is 'the most luxurious, the most modern, and also the largest' establishment in Paris (Le Figaro 3.11.1913); to the Palace-Coiffeur 'the most prominent figures of Parisian high society' come to be coiffed (Le Journal 12.11.1913). The third thing wrong with the usual account is the date. The Palace-Coiffeur opened in June 1913. To signal the splendour of the establishment a neon sign was commissioned from the company of Paz et Silva. Neon advertising did not begin modestly or tentatively, and it did not begin in 1912.

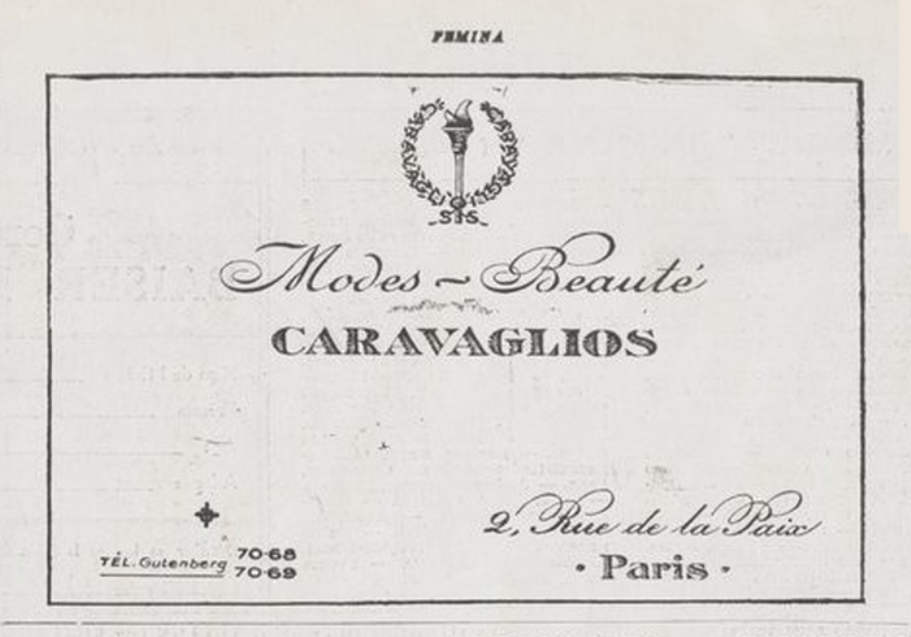

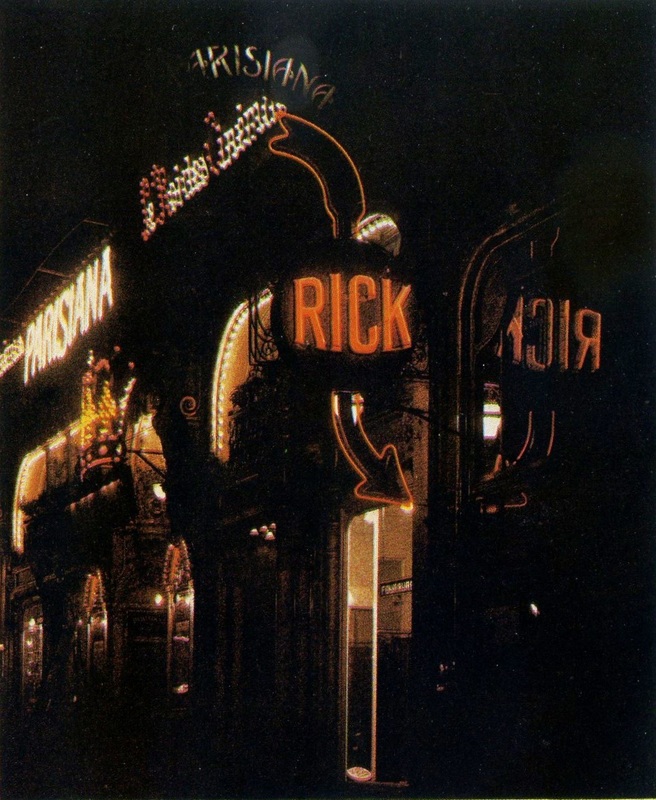

We have no photograph to show us what the Palace-Coiffeur sign looked like, but we can assume it was the familiar reddish orange, and I would guess that it spelled out the name of the salon with the elegance of the sign below, another Paz et Silva creation, this time for a high-class fashion and beauty salon on the rue de la Paix:

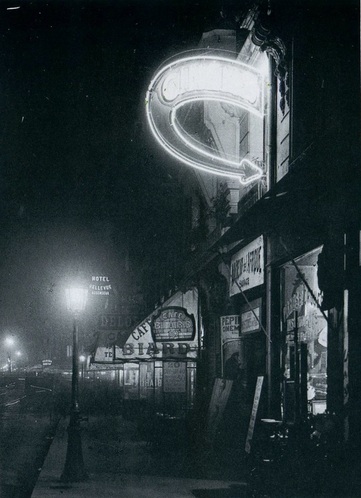

Here are two Gimpel photographs, dated 1913, of signage for Pierre Lafitte's publishing house:

Femina, Musica, Je sais tout, Vie au grand air and Fermes et Châteaux are all magazines. Editions Pierre Lafitte had offices on the avenue des Champs Elysées and the avenue de l'Opéra. This is 9-11 avenue de l'Opéra.

If the Palace-Coiffeur sign dates from June 1913, the claim to its being the first is probably no longer justified. The popular histories always follow the story of the modest barber's shop on the boulevard Montmartre with that of another, apparently more impressive sign. Here is how Rudi Stern tells it (The New Let There Be Neon, p.8):

'A year later a more spectacular neon sign, the first installed on a roof, lit up the Paris sky with three-and-a-half foot white letters spelling CINZANO.'

There are several problems with the Cinzano sign story. Firstly, sources disagree as to whether it was on the Champs Elysées or on the boulevard Haussmann. No author who says it was on the Champs Elysées gives a more precise location, whereas several sources give the location as 72 boulevard Haussmann. Here is a photograph of the boulevard Haussmann where it meets the rue du Havre. That is the Au Printemps department store to the right:

'A year later a more spectacular neon sign, the first installed on a roof, lit up the Paris sky with three-and-a-half foot white letters spelling CINZANO.'

There are several problems with the Cinzano sign story. Firstly, sources disagree as to whether it was on the Champs Elysées or on the boulevard Haussmann. No author who says it was on the Champs Elysées gives a more precise location, whereas several sources give the location as 72 boulevard Haussmann. Here is a photograph of the boulevard Haussmann where it meets the rue du Havre. That is the Au Printemps department store to the right:

As you can see, on the top of the building in the middle are seven letters spelling out CINZANO. That building is 72 boulevard Haussmann; this is not conclusive evidence as to where that first Cinzano neon sign was in 1913 because this photograph dates from the 1920s and the sign could have been put there at some point after 1913. The Cinzano sign is still there in this photograph from the 1930s:

As for the other suggested location, I have found no visual trace of a Cinzano sign on the Champs Elysées at any point in this period, and no mention in contemporary sources. Of course that doesn't mean it wasn't there, but I am inclined to think the boulevard Haussmann location is the more likely.

There are also problems with the usual descriptions of the sign. Regarding the size, almost all accounts describe the letters as white and about a metre high. Placed on a rooftop, however brightly they shine, metre-high letters are not particularly impressive.

Ulmer and Plaichinger are explicit about the colour of the sign:

Ulmer and Plaichinger are explicit about the colour of the sign:

'Cinzano was inscribed in giant letters, white against a red and blue background, clearly visible from the place de l'Opéra, on the roof of a building on the boulevard Haussmann' (Les Ecritures de la nuit, p.24).

'Cinzano was the first to use the luminescent tubes for advertising. The name, traced in white, sparkled against a curtain of red and blue tubes near the place de l'Opéra' (p.44).

'Cinzano was the first to use the luminescent tubes for advertising. The name, traced in white, sparkled against a curtain of red and blue tubes near the place de l'Opéra' (p.44).

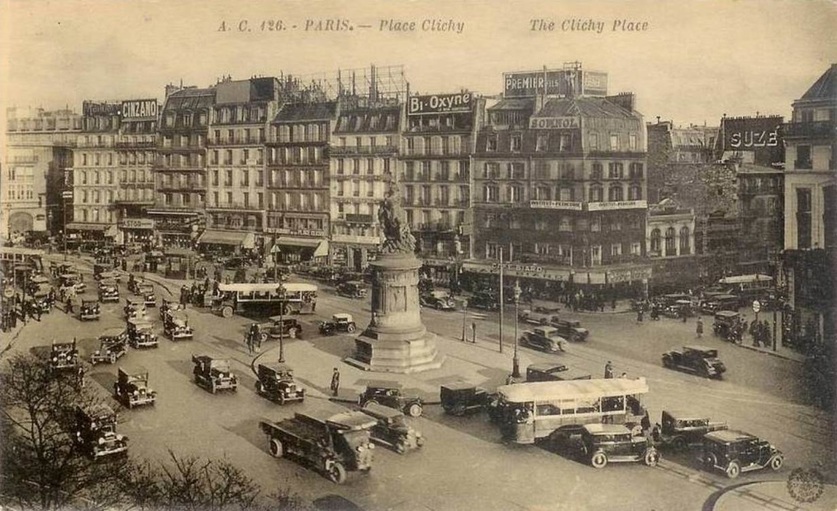

See, for example, the Cinzano sign in this 1920s photograph of the place de Clichy:

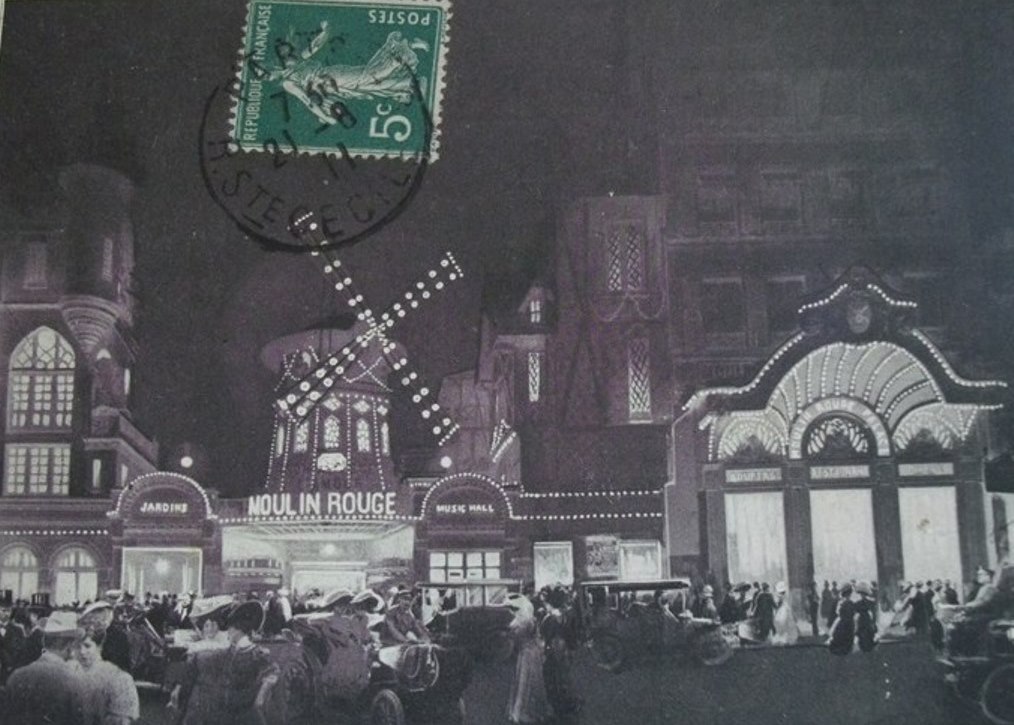

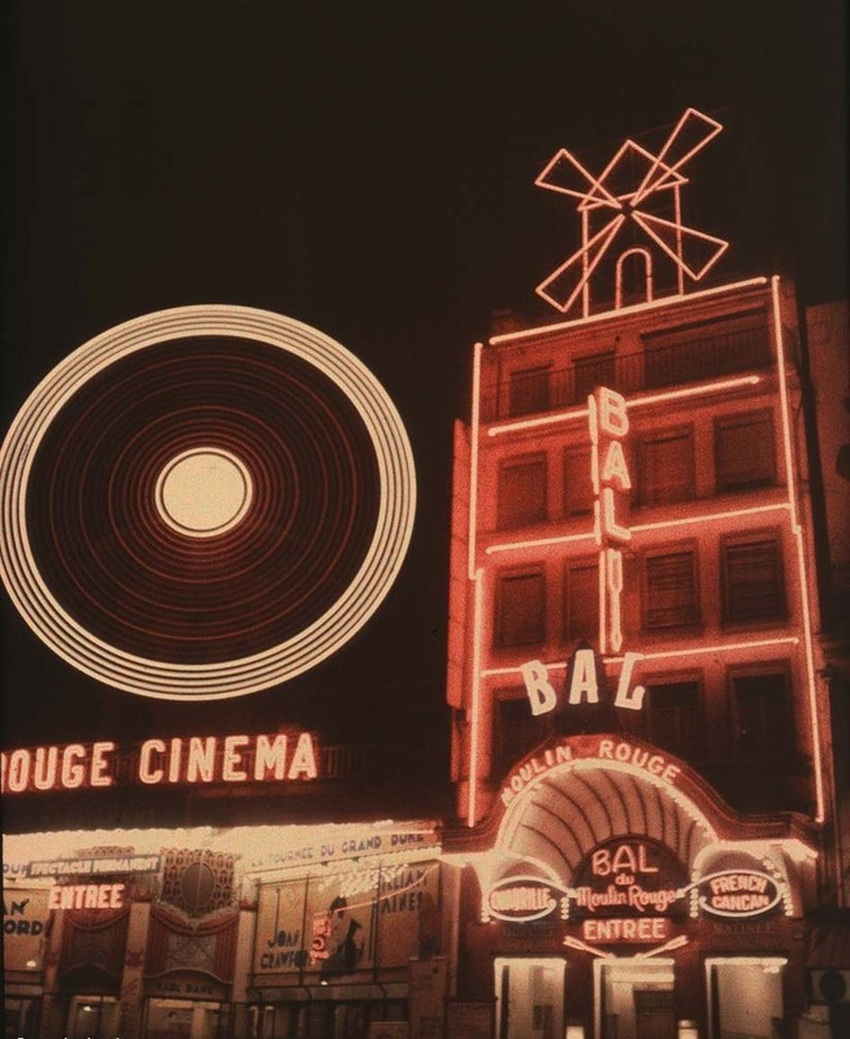

If the letters of the 1913 Cinzano sign were individual capitals, as Cinzano signs tended to be, I can't see what would distinguish them from Paris's already prevalent signage based on standard electric lighting. I'm not sure how tall are the letters spelling out, in light bulbs, MOULIN ROUGE in this image from 1911, but I'd say a metre was about right:

The letters of the CAFES CARVALHO sign below, on the place de Clichy in 1904, look to be at least two metres high:

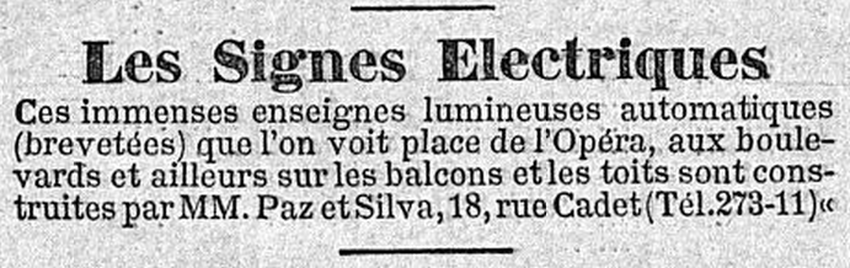

Electric signs of this type had been a feature of Paris since the previous century. This item from Le Temps of November 1899 refers to 'immense automatic luminous signs' to be found all over Paris, all installed by the Paz et Silva company:

So if in 1913 there appeared mere-metre-high white capital letters spelling out CINZANO, on the boulevard Haussmann or the avenue des Champs Elysées, I can't see who would be particularly interested, even if they were neon. If only Léon Gimpel had been sufficiently impressed to photograph them...

UPDATE [14.05.2015]

Looking more closely at Ulmer and Plaichinger's Les Ecritures de la nuit I find a further reference to the Cinzano sign, one that contradicts the two other descriptions they give. Again drawing on Fonsèque's memoirs, they describe what happened once the war was over in 1918:

'The president of Cinzano requested the relighting of the sign on the boulevard Haussmann, that had been off since August 1st 1914. "Cautiously we restored the power. The sign worked perfectly well. There were no broken tubes, but the letters and the glass were covered with a thick layer of dust. It is worth noting that the light was barely diminished, the red rays easily passed through the dirt on the tubes"' (p.28).

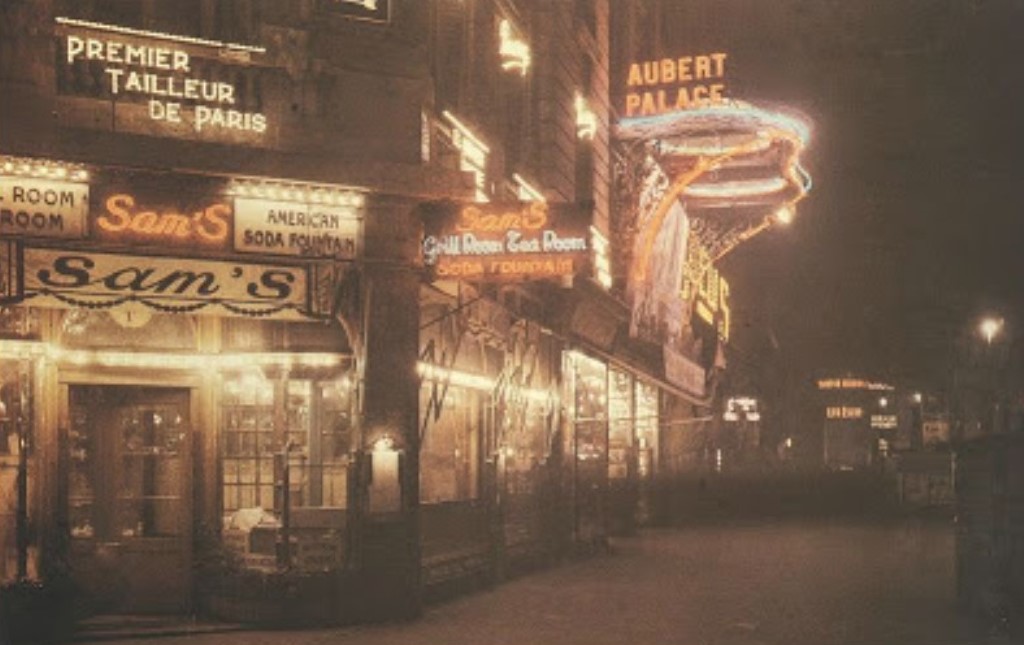

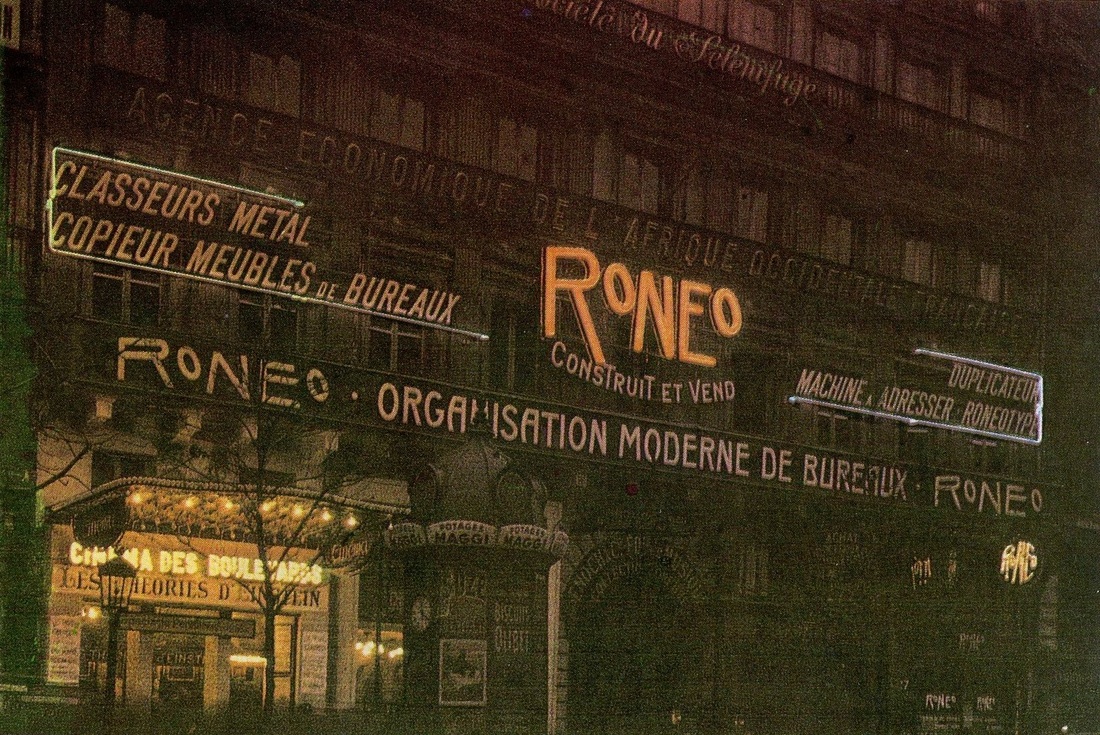

This makes clear that the letters were red not white. The sign must have been very much like the reddish-orange Cinzano sign just visible in the background of this 1925 photograph of the boulevard des Italiens:

Looking more closely at Ulmer and Plaichinger's Les Ecritures de la nuit I find a further reference to the Cinzano sign, one that contradicts the two other descriptions they give. Again drawing on Fonsèque's memoirs, they describe what happened once the war was over in 1918:

'The president of Cinzano requested the relighting of the sign on the boulevard Haussmann, that had been off since August 1st 1914. "Cautiously we restored the power. The sign worked perfectly well. There were no broken tubes, but the letters and the glass were covered with a thick layer of dust. It is worth noting that the light was barely diminished, the red rays easily passed through the dirt on the tubes"' (p.28).

This makes clear that the letters were red not white. The sign must have been very much like the reddish-orange Cinzano sign just visible in the background of this 1925 photograph of the boulevard des Italiens:

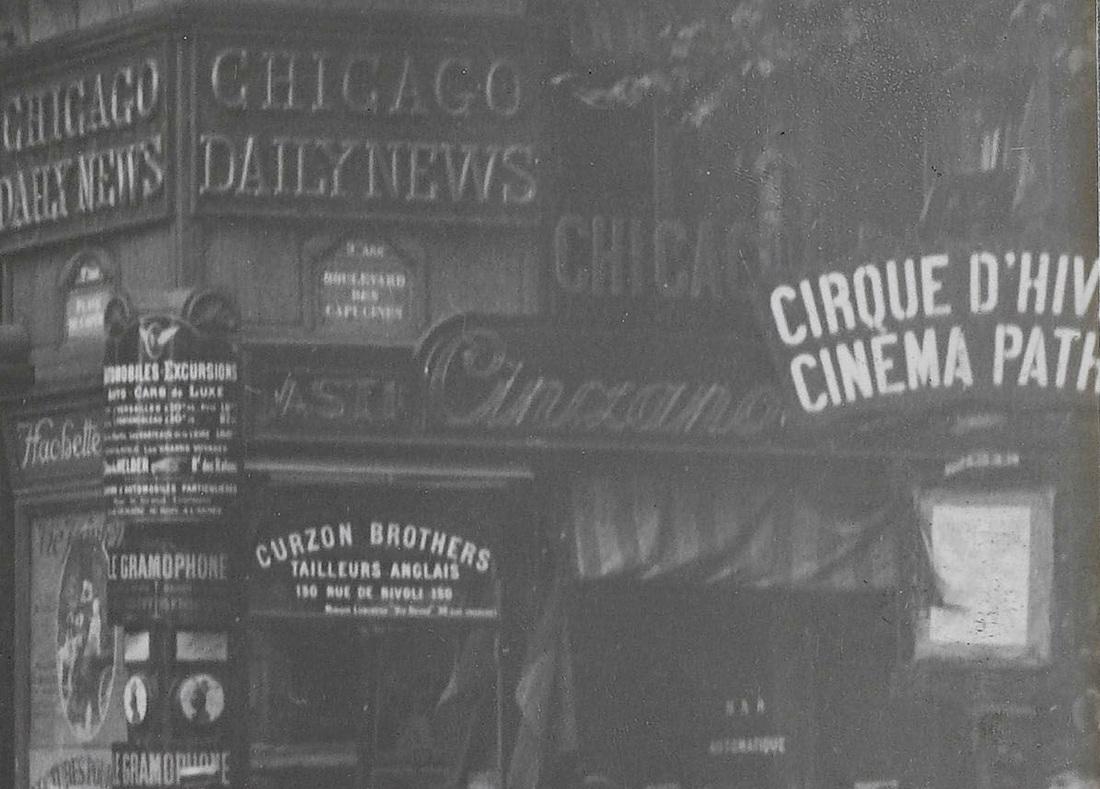

Ulmer and Plaichinger describe another pre-war Cinzano advertisement, reading 'Asti Cinzano Vermouth' in continuous lettering above the Quisisana bar on the place de l'Opéra. This sign, near the corner of the place de l'Opéra at 8 boulevard des Capucines, was photographed by Charles Lansiaux in 1914:

In another photograph by Lansiaux we can see the Cinzano sign of the Quisisana bar from the side:

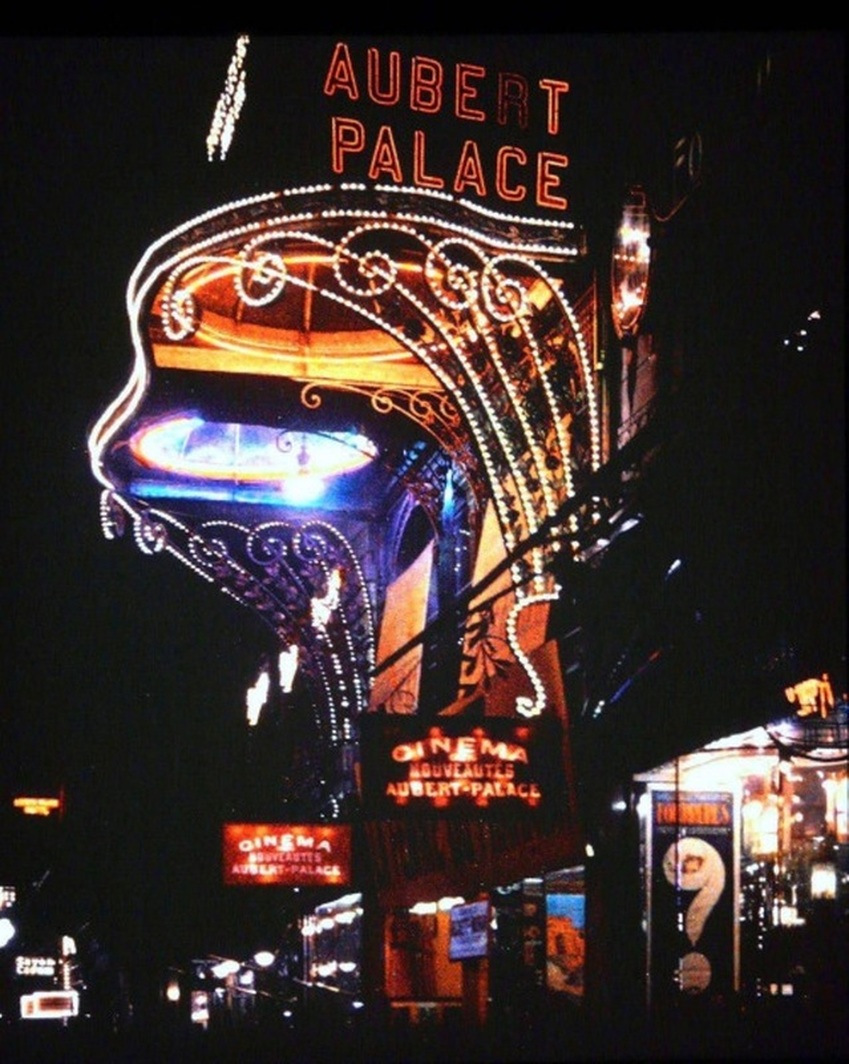

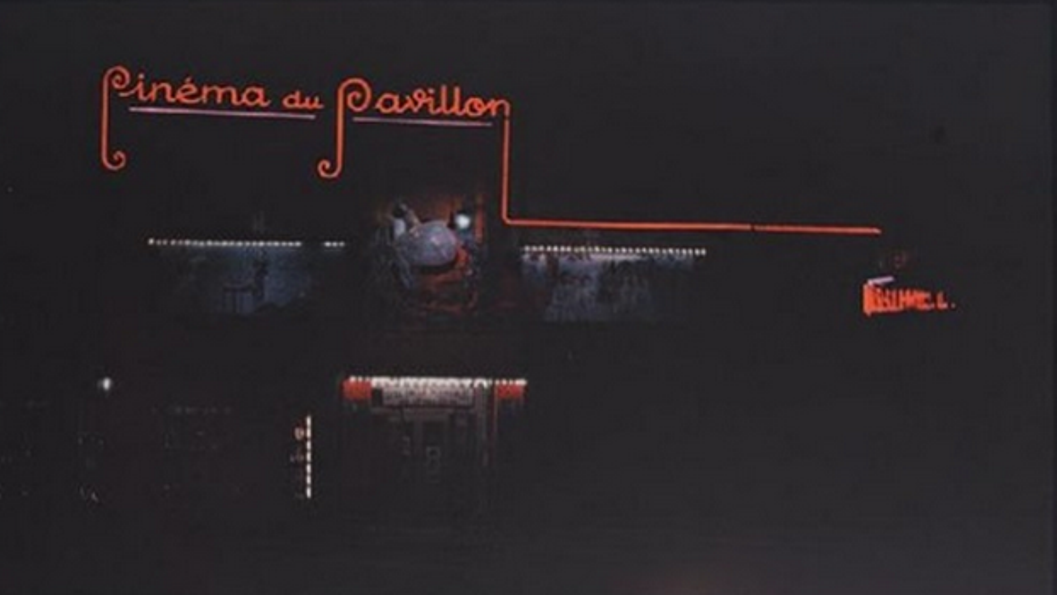

Léon Gimpel maintained his interest in photographing neon and in the 1920s produced a series of memorable images that make him de facto the first historian of neon. I have reproduced some of the cinema-related ones below, all post-war, but the really important Gimpel images, for today's historian of neon, are those of neon signs made between 1910 and 1914.

References

- Art & Pub: art et publicité 1890-1990, catalogue de l'exposition (Editions du Centre Pompidou 1990)

- John Compton, 'The Night Architecture of the 'Thirties', The Journal of the Decorative Arts Society 1890-1940, 4 (1980)

- Christoph Ribbat, Flickering Light: A History of Neon (Reaktion 2013)

- Rudi Stern, The New Let There Be Neon (ST Publications 1996 [1988])

- Bruno Ulmer & Thomas Plaichinger, Les Ecritures de la nuit (Syros 1987)