|

The Cine-Tourist has gone into vanilla mode while he recovers from the end of term party.

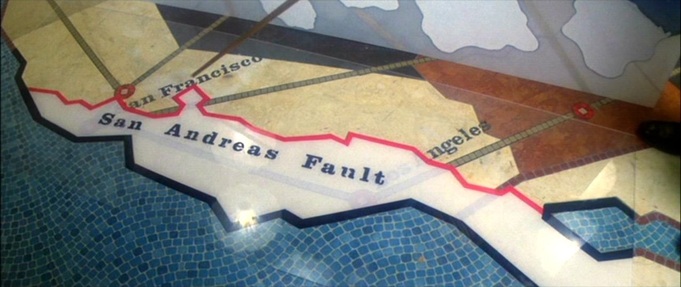

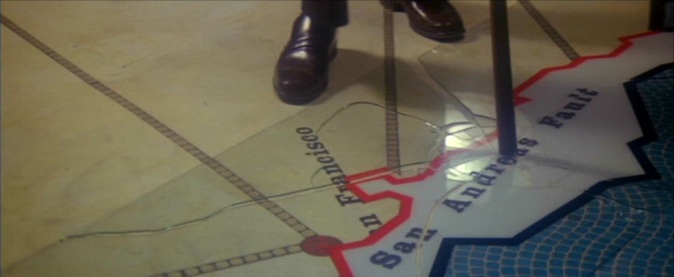

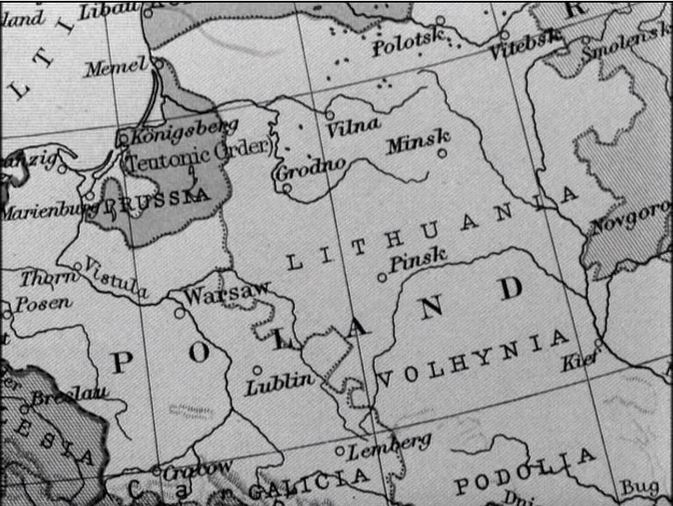

That's me, in my most comfortable armchair, looking at a big map and wondering what it all means. I've read all those newspapers and they don't help. Discursive mode will resume soon. Meantime it will just be pictures of me looking at maps and wondering what they all mean. A designed map is used as expressive décor, in the manner of L'Herbier's L'Argent three years earlier (see here), and though the film gives no credits, this must be more of Lazare Meerson's cartographic work: There's another, purely background map, of no graphic consequence:

There are two map moments, an idyllic prologue with Tommy's parents as figures in a landscape, with a map that presumably situates that landscape, then, towards the climactic end, Tommy's stepfather with a map signifying world domination. See here for Ken Russell links, 'in his magnificent memory', at Film Studies For Free.

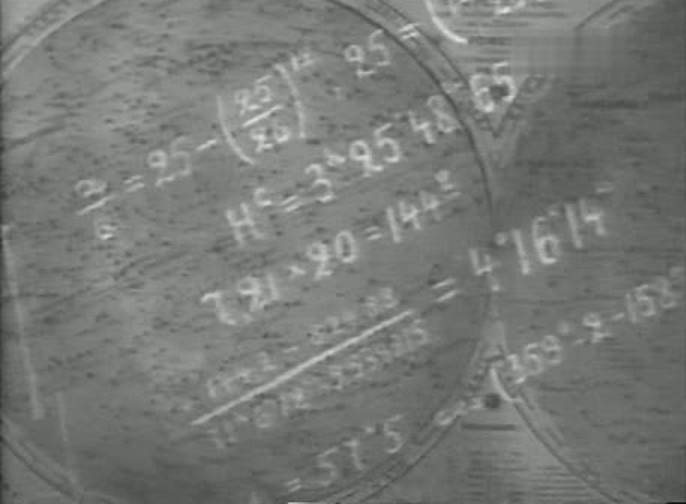

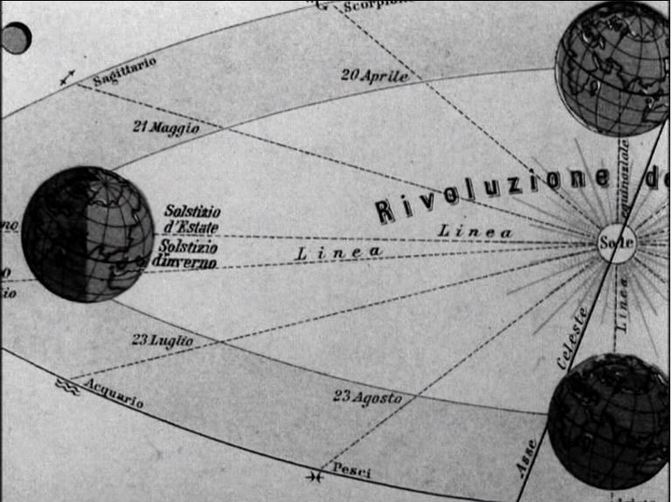

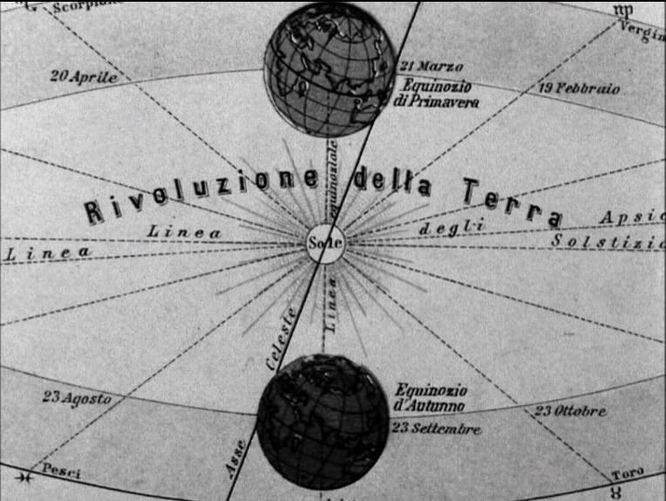

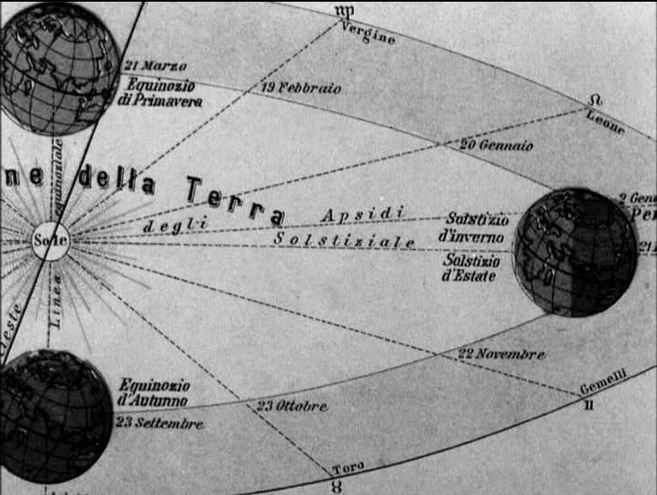

Gance's anticipation of the world's destruction begins with a turning globe in close-up. The globe motif is troped upon soon after by this telescopic view of the approaching comet, as if the night sky were a distorting mirror in which the globe is reflected: Planispheric maps of the celestial spheres, in close-up, develop the motif: Maps of the world and the skies are both seen in the lecture room where the protagonist presents his findings on the impending catastrophe: But by the climax it is the world and its constituent parts that are focused on, as we are about to witness the destruction of these places each in turn, returning to extreme close-ups of the map in the film's final cartographic moments:

Another American production in Paris, but this time actually in Paris, with authenticity derived from real locations and a local supporting cast (including Brigitte Bardot).

No maps of Paris to help us find our way around, but the 'worldliness' of the American officer to whom a French woman goes looking for work is suggested by the décor of his office (he will give her work in exchange for sex): The deformation of the world map that introduces Rollin's film is the correlative of the disorientation experienced by the protagonists in a city they don't recognise and around which they cannot find their way.

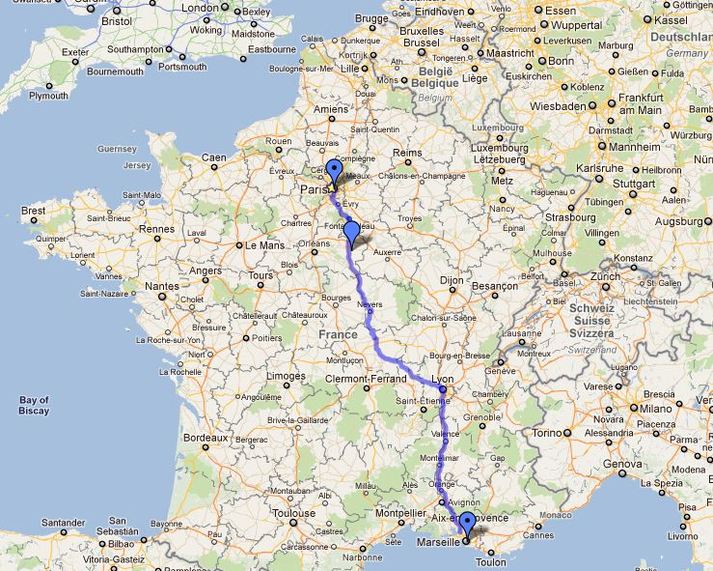

The city is Paris (more exactly Ménilmontant), made strange by the presence of strangers, speaking strange languages, singing strange songs. The story of Lola is little more than that of the preparations made by its male protagonist, Roland, to leave Nantes. This story is framed by the return to Nantes of Michel, father of Lola’s child. He has been seven years on a South Pacific island, Matareva, as if he has arrived in Demy’s film from Mark Robson’s 1953 Return to Paradise (which Roland goes to see at a cinema in Nantes in the course of the film). Michel’s arrival is the counterweight to the departure not only of Roland but also of the little Cécile (who has run off to Cherbourg), of Frankie and the other sailors, heading back via Cherbourg to the U.S., and of Lola and her son, who are leaving for Marseille. Of all these only Roland is associated with maps. He passes a map of France as he leaves his place of work, after having been fired. In his room he studies closely a map of the ‘Five Parts of the World’, and the man who offers him louche employment as a courrier (flying from Amsterdam to South Africa) explains the itinerary by pointing to a map.

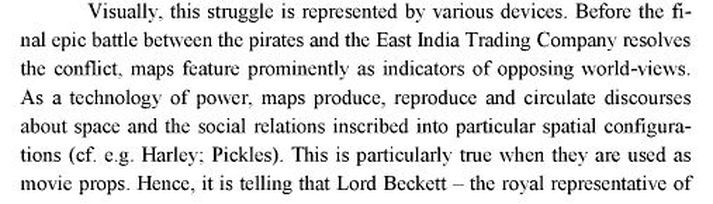

Heike Steinhoff, Queer Buccaneers: (De)Constructing Boundaries in the Pirates of the Caribbean Film Series (Berlin: Lit Verlag, 2011), p.116.

‘Truffaut was furious when the locations found in Corsica did not correspond to what he had imagined. Roland Thenot, his production manager, recalls that Truffaut left two hours after he got off the plane, having rejected two or three locations that he did not find exotic enough. Marcel Berbert says he got a phone call from Truffaut that weekend, when the crew was ready to leave for Corsica on Monday to start organizing the shoot: having decided to cancel everything, Truffaut was very excited about New Caledonia (in the film, this would be the original destination of Julie Sorel and her sister Berthe). Horrified by the distance (40000 miles) Berbert, consulting a map, proposed Reunion as a compromise solution.'

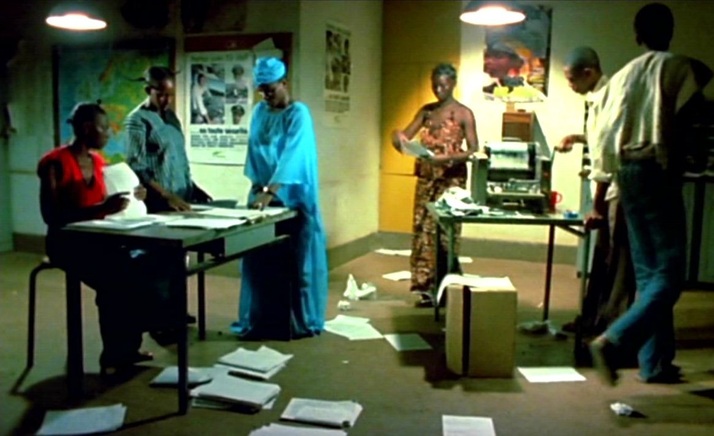

Carole Le Berre, François Truffaut At Work (London: Phaidon, 2005), p.115. There are two map rooms in Finye. The first, where the student protesters are printing clandestine tracts, has a world map, a map of Europe and another too indistinct to be made out. The world map is the dominant, signifying the students' openness to the world beyond Mali, and framed from different angles to emphasise the variety of perspectives that such openness entails. The second, the military governor's office, is dominated by a map of Mali, represented as isolated not only from the world but even from its immediate neighbours, removed from its African context. Within its borders, the country has rivers, a lake, varied terrain and differentiated regions, but beyond its borders there is nothing:

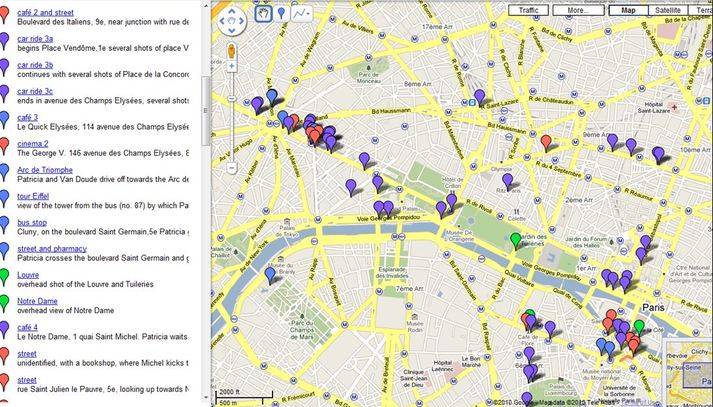

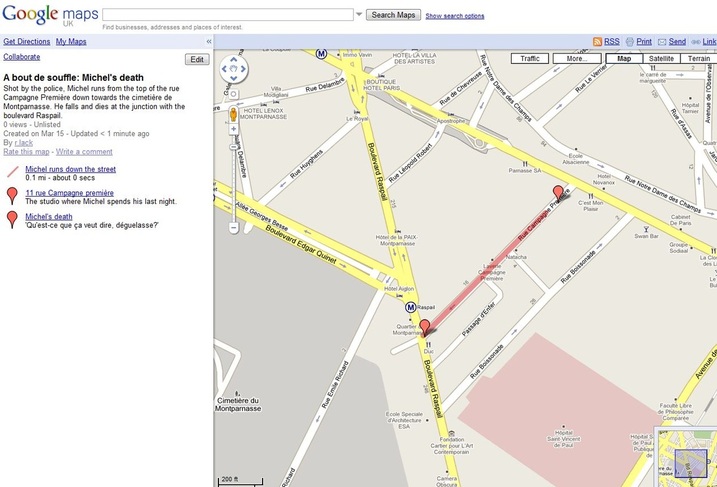

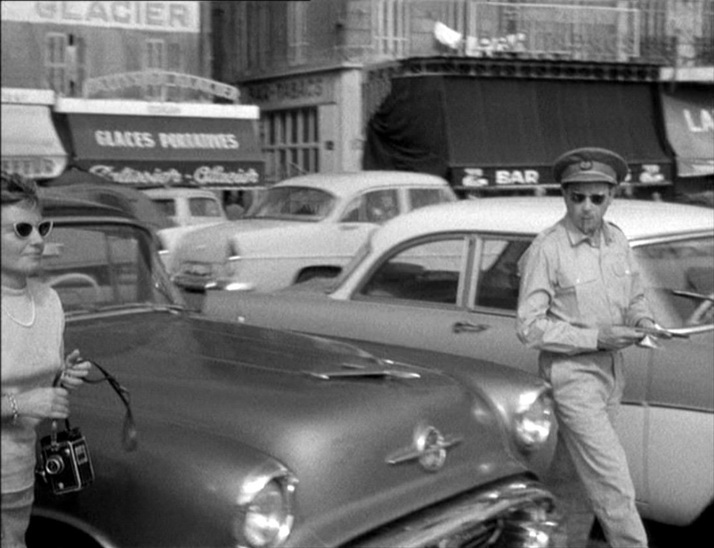

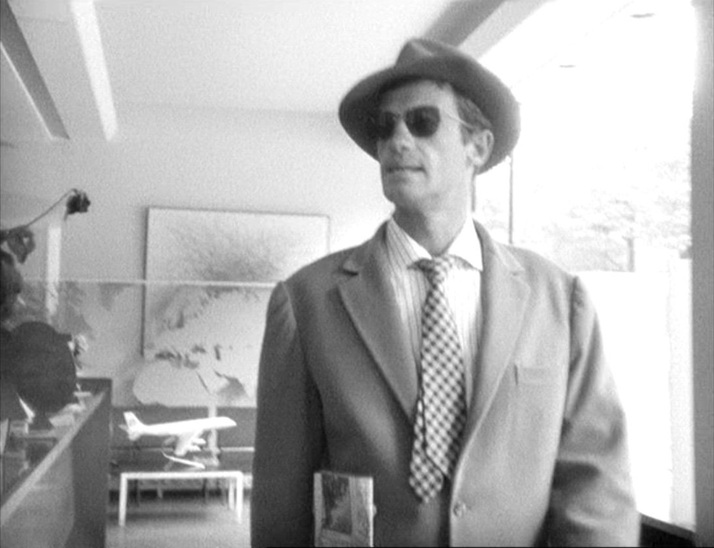

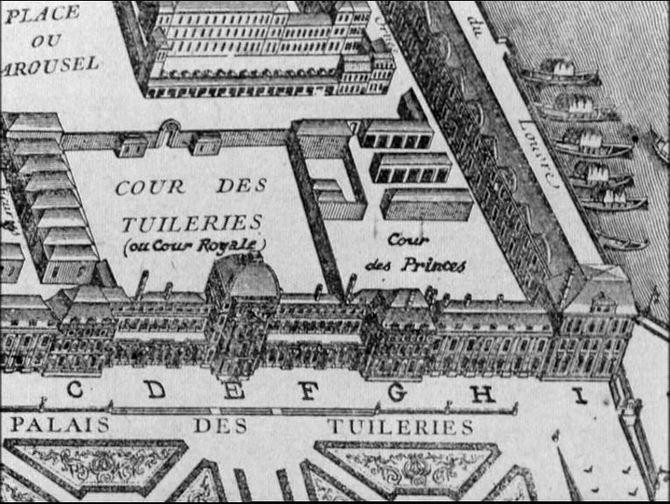

The map of the film can be very exactly drawn, from its opening in Marseille, through Michel’s journey up to Paris and his movements in and around the city, to the film’s close at the junction of the rue Campagne Première and the boulevard Raspail. The maps in the film are incidental, of interest only to the collector. The first is in the hand of the American officer whose Oldsmobile 88 Michel will steal (see the IMCDB here for more detail on the cars in A bout de souffle). The officer’s wife has in her hand a camera: it's a rare pleasure to find a film with map and camera in the same frame (see here the four other cameras in A bout de souffle). There are several maps in the travel agency on the Champs Elysées where Michel goes to find Tolmatchoff, all adjuncts of the film’s preoccupation with the world beyond France: The last map is in the film's last interior, the apartment on the rue Campagne Première where Michel and Patricia spend the night. The décor of the bedroom includes a blow up of an antique ‘perspective’ map of Paris: This seems to have been a fashion. A similar décor occurs in another Belmondo film from the same year:

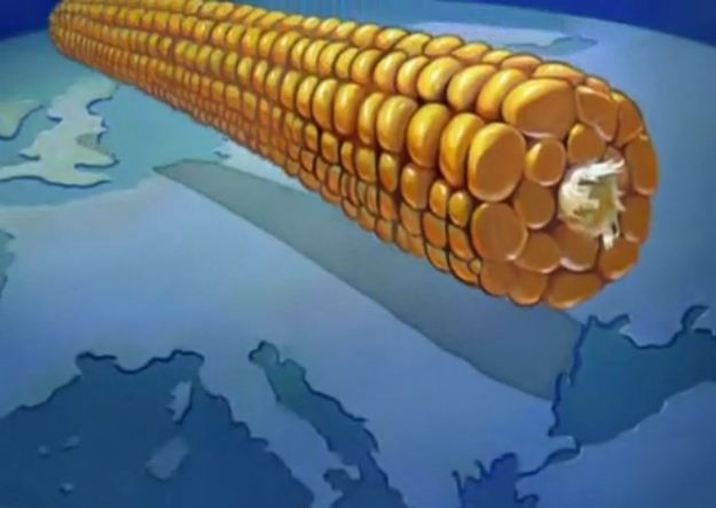

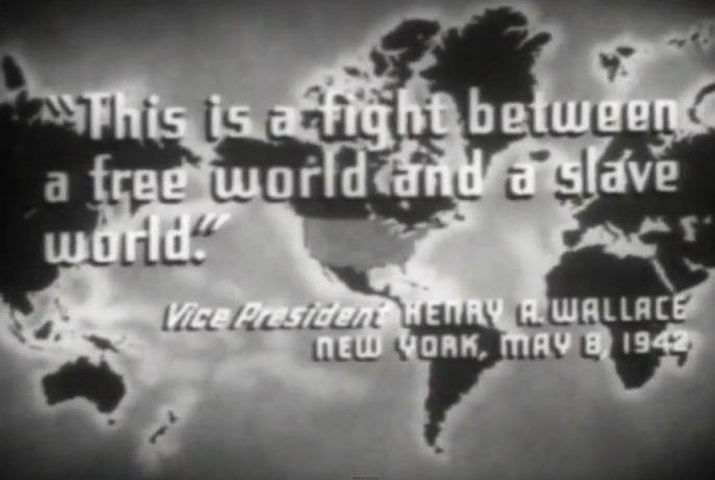

Richard J. Lesowsky, ‘Cartoons Will Win the War: World War Two Propaganda Shorts’, in A. Bowdoin Van Riper, Learning from Mickey, Donald and Walt: Essays on Disney's Edutainment Films (Jefferson NC: McFarland & Co., 2011), pp.46-47.

Richard J. Lesowsky, ‘Cartoons Will Win the War: World War Two Propaganda Shorts’, in A. Bowdoin Van Riper, Learning from Mickey, Donald and Walt: Essays on Disney's Edutainment Films (Jefferson NC: McFarland & Co., 2011), pp.47-48.

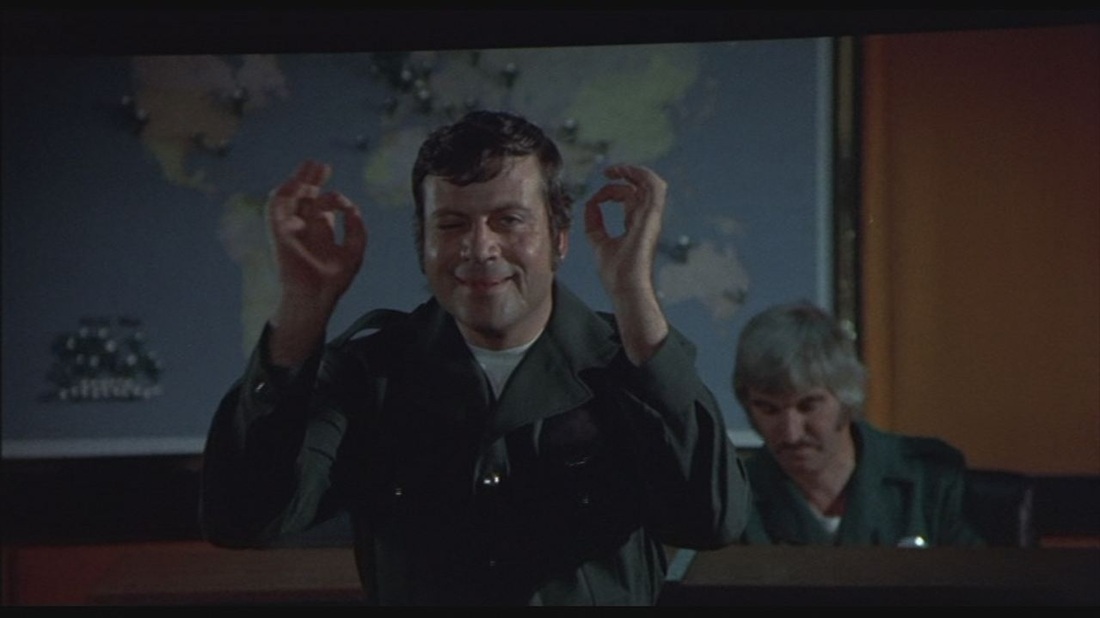

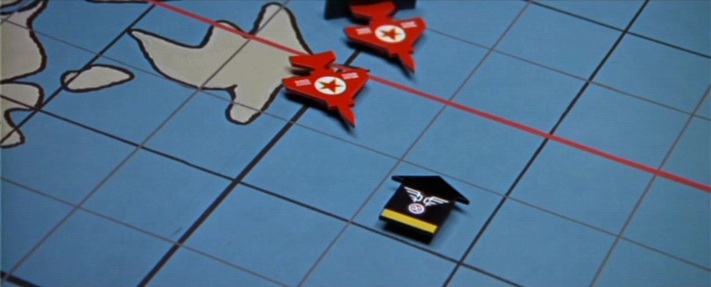

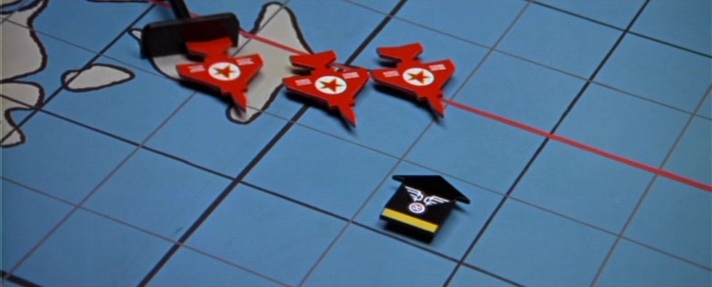

The third in the Harry Palmer series is still deriving material out of its difference from Bond. The map of London on the wall of Palmer's dingy office contrasts with the world maps on walls in early scenes of Bond films. Now a private detective, Palmer's sphere of activity is local, not global. When Palmer does travel, he faces the un-Bondlike challenge of finding on a map an address in a phone book. Ou maps pull back from this exactly pinpointed address in Helsinki to a more general view of the Baltic region, and even when - in Ed Begley's centre of operations - we have the familiar world map that signifies megalomania, the Baltic region is marked by a concentration of lights. In a further contrast with the Bond corpus, Syd Cain's operations rooms in Billion Dollar Brain are deliberately modest affairs compared with, for instance, the spaces created by Ken Adam for that year's Bond film (even if that is clearly the same map on the wall, above and below - both scenes were shot at Pinewood) : For its climax Billion Dollar Brain shows opposing forces plotting the final confrontation, each on their own maps: These last two map scenes both show humans attempting to arrange the world my arranging things on maps. This is the complement of the film's nature motif (as in the Alexander Nevsky-like climax on the ice). Human endeavour vs untamable nature is an opposition neatly foregrounded in this dissolve from the penultimate to the last sequence:

Two parallel boardroom scenes mark a shift in attitude for the female protagonist. In the first she is all powerful, and the initial staging whereby she is blocked by the standing man in the centre is ironic. The framing and staging of the rest of the sequence will establish clearly her dominion over the men in the boardroom. Her positioning in relation to the two maps contributes to that impression.

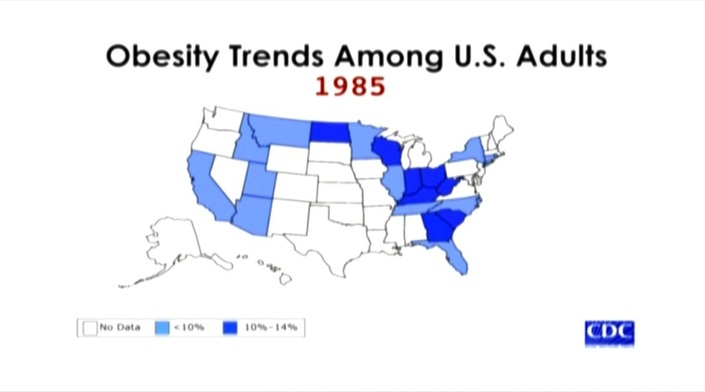

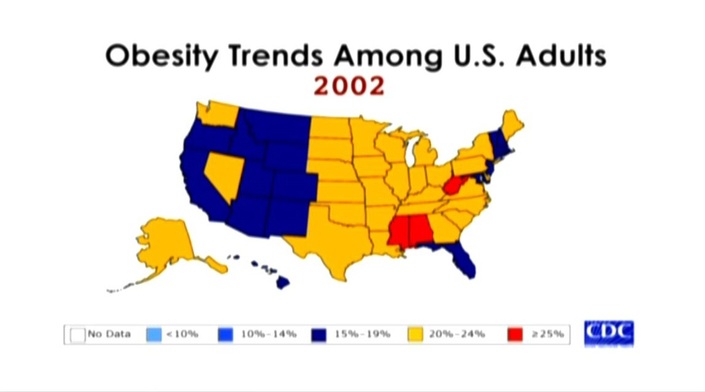

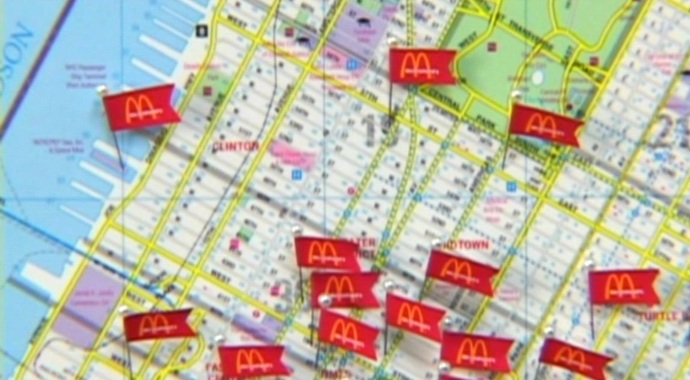

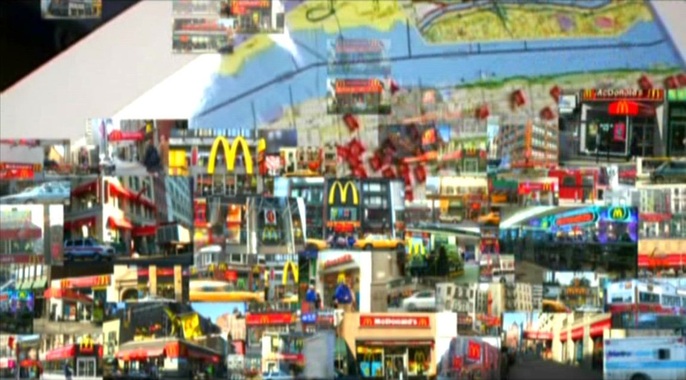

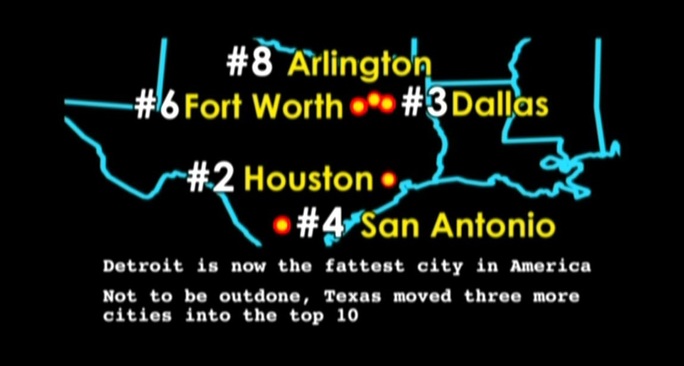

In the second sequence the initial staging indicates a diminution of power. Though this time she is immediately visible, she is off-centre in relation to the maps. In the course of the sequence there are framings that match those of the earlier sequence, and it is her change in dress and demeanour, rather, that underscore the what has changed in the cours of the narrative. Animated maps to illustrate a point are common in documentaries (hence their use in the 'News on the March' section of Citizen Kane), and Super Size Me has three striking instances. Spurlock also, however, 'animates' a map profilmically by progressively sticking flags and then photographs onto a map of Manhattan:

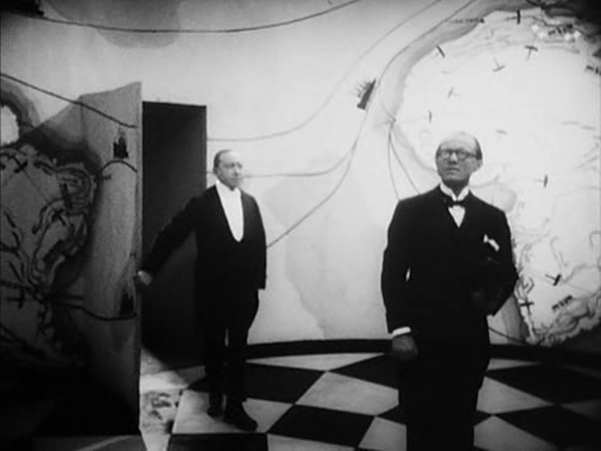

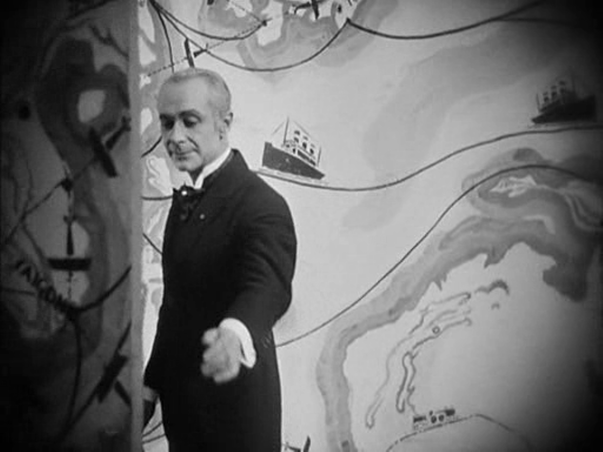

Of the five spaces in which maps figure in L'Argent, the first is the most spectacular. We follow an agent of the banker Gundermann as he is led by a butler into an antechamber decorated to represent the reach of the banker's power. In combination with the cinematography, this mise-en-scène also displays the distorting, disorienting force of money. The second space is more conventional: in their modest apartment. the naive adventurer hero Hamelin and his wife Line examine a map of the Americas, though it becomes a mere backdrop to the expression of their love for each other. Later, in the same space, Hamelin explains his plans to the banker Saccard, with a view of a more detailed map of the region that Hamelin proposes to exploit for oil. We first see the scene diffusely, in a mirror, before passing to two readable mapshots. Next, in a room at the airport from which Hamelin will take off on a solo flight across the Atlantic, Line looks on in terror at the thought of the danger he will face. He enters, first seen as a shadow cast over a map of Europe and North Africa, which then becomes the backdrop to their passionate embrace on parting. The most often shown space in the film is the banker Saccard's office, dominated by a map of the world. Against this backdrop we see Saccard manipulate markets on a global scale, we see him attempt to seduce Line, and finally we see him arrested for fraud. Prior to Saccard's arrest we see Hamelin in Guyana (here with Antonin Artaud as Saccard's secretary). A map on the wall serves as establishing decor, but it cannot compete with the cartographic spectacles on display back in Paris. Hamelin returns to France and we see two policemen waiting to arrest him in the same room at the airport where he had kissed Line farewell. This time we see more of the cartographic decor, including the west coast of France: The film's denouement involves Line approaching Gundermann, and we see again, in more detail, his spectacular antechamber: The decor of L'Argent is one of Lazare Meerson's finest achievements, especially in the cartographic configurations of this last, framing space.

When, in 2011, I first posted about the maps in this film I said they appeared in only one scene. Seeing the film again this afternoon at the ICA, in a beautiful print, I spotted my mistake in not spotting the very large globe, above. Many thanks to The Badlands Collective for organising the screening, on the film's 40th birthday. Maps appear in Barry Lyndon in only one scene, but they cover the known world, from Asia through Africa and Europe to the Americas. And there is a globe on the table in front of the first map.

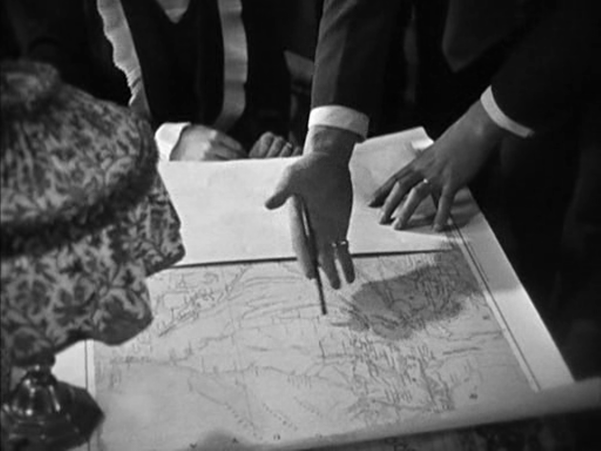

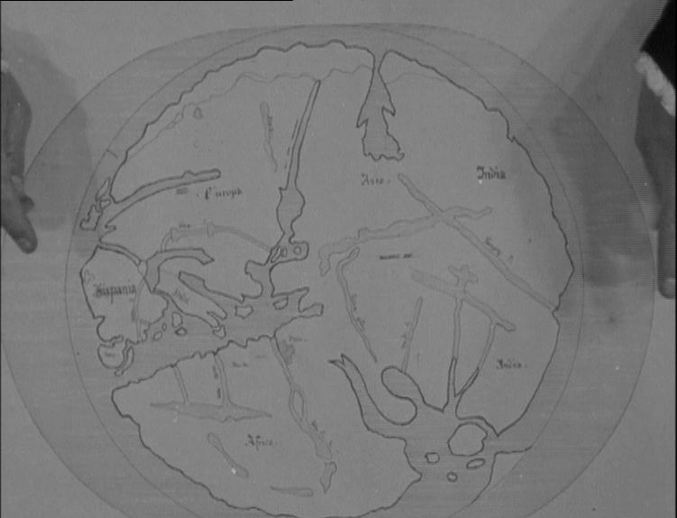

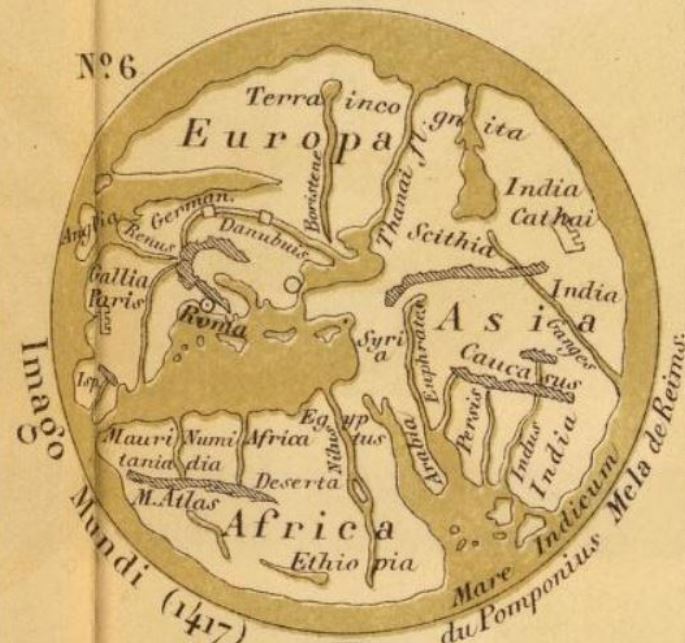

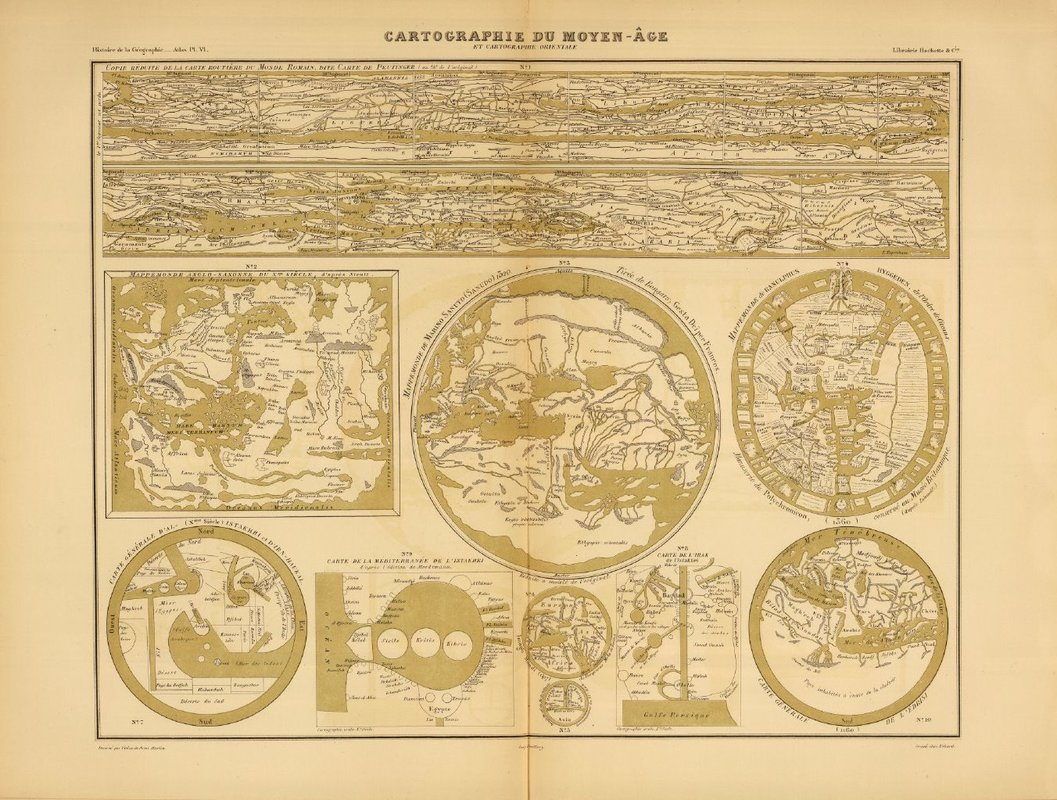

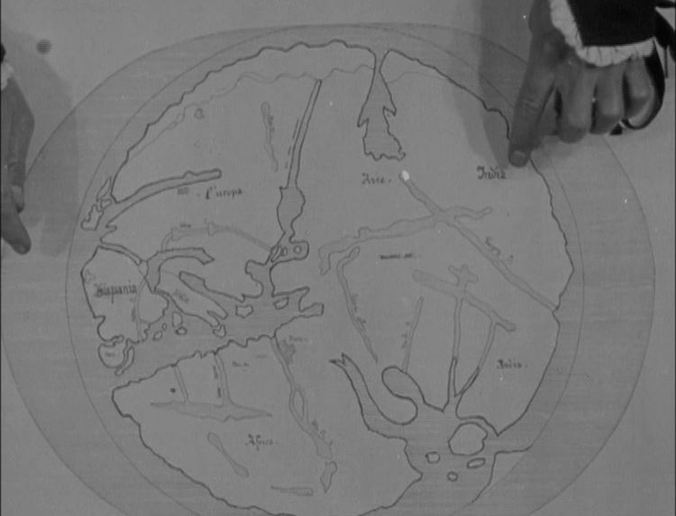

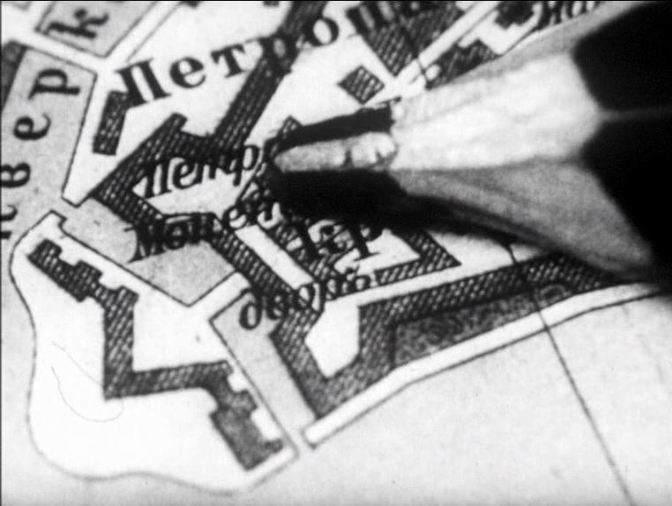

The model for the map used here appears to be this, a nineteenth-century configuration of a fifteenth-century map: This is an 1874 Hachette publication. The map is based on an illustrated initial (the O of Orbis) in a 1417 manuscript of Pomponius Mela: The scene in Christophe Colomb is the earliest instance I know where a map is discussed, pointed at and made available to be read by the spectator. Richard Abel (who attributes this film to Louis Feuillade, though a recent Gaumont edition gives it to Etienne Arnaud) signals the unusualness of the shot: ‘The first scene, in which Columbus explains his plan to the Genoa officials, is filmed in full shot, but includes a cut-in to an unusual high angle close up of a map (approximating a POV shot), with his hands coming in from the top of the frame to point and gesture.’ See Richard Abel, The Ciné Goes To Town: French Cinema 1896-1914 (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 1994), p.273. Columbus can be seen clinging determinedly to his map in four further scenes of the film: ‘What doe the cinema of space par excellence think about when it dreams of Baudrillard? It thinks about lines (dialectical polarity), about maps (the precession of the map over the territory), about networks (reversibility and the circular forms of commutation), about hyperbola (potentialisation), about interstices (viral strategies) and about spirals (ecstatic enthusiasm and thought as precipitation). In short, it thinks about fatal spaces of resistance.’

Jean Baptiste Thoret, ‘The Seventies Reloaded (What does the cinema think about when it dreams of Baudrillard?)’, translated by Daniel Fairfax, Senses of Cinema 59 (2011), originally published in Les Cahiers de L’Herne, 84 (February 2005) ‘Workers do not produce themselves, they produce a power independent of themselves. The success of this production, the abundance it generates, is experienced by the producers as an abundance of dispossession. As their alienated products accumulate, all time and space become foreign to them. The spectacle is the map of this new world—a map that is identical to the territory it represents. The forces that have escaped us display themselves to us in all their power.’

Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (London: Rebel Press, 1983 [1967]), p.16. |

|